(Deutschen Archaologischen insituts, Rome, neg. 54.367)

Frothingham’s arrival will be fatal to us. If this American remains in Rome, he will surely get hold of it all; he will take the cream, and leave us nothing but the skimmed milk.”

These bitter words were written in a letter by the Danish brewer and patron of the arts, Carl Jacobsen, founder of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, to his agent in Rome, Wolfgang Helbig (18 November 1895; NCG Archives). The matter concerned the competition for the best pieces of ancient sculpture and other antiquities on the Roman art market.

The University Museum on the Roman Art Market

(Photo from glass negative in the Castle Museum, Nottingham.)

(Photo from glass negative in the Castle Museum, Nottingham)

In mid-October 1895 Professor Arthur L. Frothingham from Princeton arrived in Rome as the newly appointed director of the American Academy. During the years 1895 to 1898 he was associated with the University of Pennsylvania Museum, acting as the Museum’s intermediary on the Roman art market. His arrival on the Roman stage disturbed Carl Jacobsen, who was not accustomed to having serious competitors when buying antiquities in Rome. Frothingham, however, did not present any real threat at first; he did not buy antiquities, but instead used most of his energy trying to secure models and facsimiles of Etruscan tombs and plaster casts of monumental Roman sculpture. After months of negotiating, he succeeded in having casts made of the Trajanic arch at Benevento.

Back in America, the collections of the University Museum were expanding. A main contributor to the creation of the Museum’s Mediterranean Section during the early years was Mrs. Lucy Wharton Drexel (1838-1912). She was married to Philadelphia banker Joseph William Drexel and was “a woman of large means,” as the curator Sara Yorke Stevenson later wrote (University of Pennsylvania Museum Archives [UPMA]; letter to J.R. Coolidge, 18 February 1901). Mrs. Drexel was first and foremost a passionate collector of fans. As her donated fans accumulated rapidly in the Museum galleries, Mrs. Stevenson talked to her about spending her money on “something more serious”: the collecting of ancient sculpture, as she recalled in the same letter. Mrs. Drexel agreed, and this is where Frothingham came into the picture.

In early 1896 he deplored the fact that “there are absolutely no antiquities for sale neither in Etruria, nor in Rome” (UPMA; letter to Stevenson, 30 January 1896). However, some months later, he reported to Mrs. Stevenson and the director of the Museum, William Pepper, that a group of marbles unearthed in the area around Lake Nemi had apparently turned up on the art market (UPMA; letters to Stevenson, 26 October 1896, and Pepper, 29 November 1896). Later that year, Frothingham bought the marbles (UPMA; letter, Frothingham to Pepper, 8 December 1896). The payment for the lot was sent in the new year (UPMA; Accounts List entries, 17 February 1897: Nemi marbles $603; 9 March 1897: Nemi marbles $2490.29), and during the summer of 1897, the marbles were shipped to the States. A few more items from the same site may have been acquired later that year.

Nemi and the Sanctuary of Diana

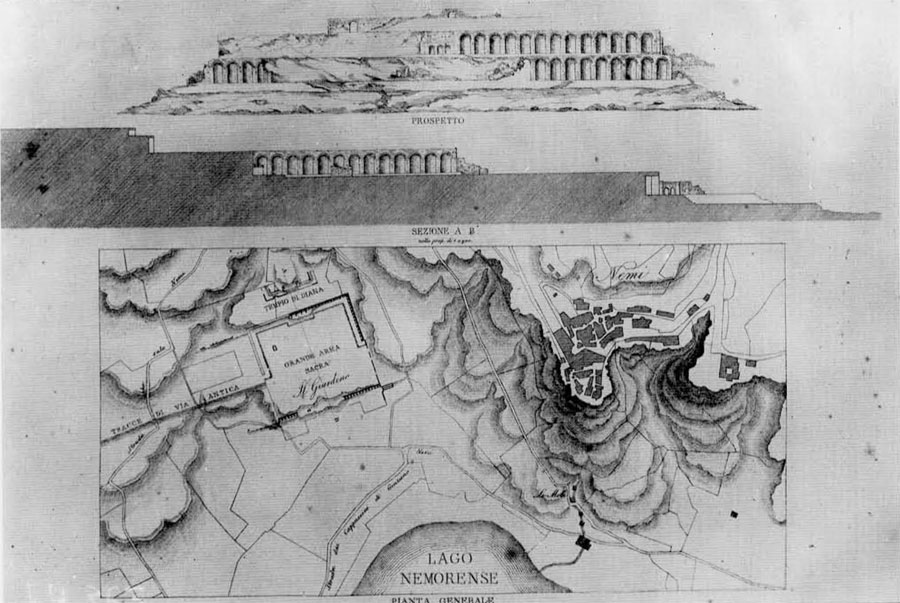

Nemi, where Frothingham’s acquisitions had been found, is a picturesque locality situated some 25 kilometers southeast of Rome in the forest-clad Alban Hills. The small medieval town of Nemi itself is situated high on a rocky spur overlooking the volcanic crater lake of the same name. Down near the shore of the northern end of the small lake lies the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis, or Diana of the Rrove (see Fig. 4).

The Sanctuary had a few years earlier acquired considerable international fame through James C. Frazer’s book, The Golden Bough, which first appeared in 1890. This work, which was to influence the world of scholarship and art in the century to come, took as its point of departure the Sanctuary and its strange priesthood, the runaway slave-king, the rex nernorensis. Moreover, extensive excavations initiated on a vast scale in 1885 added flesh to the bare bones of mythology (MacCormick and Blagg 1983).

The impressive remains of the ancient terracing walls on which the Sanctuary was constructed had been known for centuries, and we are informed of occasional finds from the site as early as 1554 (Fig. 1). However, it was not until the late 19th century that proper investigations were undertaken. The land where the Sanctuary is situated was called Ilk Giardino, the Garden. It was the property of the local prince living in the Nemi castle (today called Castello Ruspoli after its recent owners). The late 19th century proprietor was Prince Filippo Orsini. He excavated the central terrace of the Sanctuary in collaboration first with the British ambassador in Rome, Lord Savile (1885), later with the Roman art dealers Luigi Boccanera (1886-1888), Eliseo Borghi, and Alfredo Barsanti (1895).

The chief purpose of Orsini’s undertakings was to unearth art objects, primarily sculpture, to sell on the international art market. As the Sanctuary had been destroyed during antiquity, probably by a landslide, many sculptures remained in situ. Orsini’s success was therefore extraordinary, and finds soon turned up in museums in Europe and the United States. The sculptures found by Orsini that can be traced today are mainly housed in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (Copenhagen), the Castle Museum (Nottingham), and the University of Pennsylvania Museum (Philadelphia).

During this century, the Sanctuary has been a focus of scholarly research. Particularly in the period of the Fascist regime in Italy, there was considerable interest in the archaeological remains of the Lake Nemi area. Most remarkable was the draining of the lake and the raising from its bottom of two early Imperial floating palaces. This enterprise took place between 1927 and 1932. In the same period (1924-1928), a small theater and part of a baths building were excavated in the Sanctuary (Morpurgo 1931; Ucelli 1950). Since 1989 excavations have been taking place on the main terrace of the Sanctuary as part of an ambitious study program undertaken by the Soprintendenza archeologica per it Lazio (Archaeological Superintendency of Lazio), directed by Dr. Giuseppina Chini (Chini 1993, 1995; Ghini and Rizzi 1996).

The Sanctuary of Diana is an extra-urban sanctuary. It is situated within the very heartland of Latin and Roman territory, a region that was also the center of the most ancient and highly venerated cults. Nearby, on the second highest point of the Alban Hills (in antiquity Mons Latiaris, today Monte Cavo), is the ancient federal sanctuary where the Latin and Roman peoples worshiped Jupiter Latiaris. The role of federal sanctuary was taken over by the Sanctuary of Diana Nemoreiisis around 500 BC. This Sanctuary was located within the territory of the Alban town of Aricia from where it was administered.

It remains uncertain when the cult was established by Lake Nemi. Iron Age votives are known from the site; however, none have been found in situ. It is not until the 4th and 3rd centuries BC that finds in the Sanctuary become plentiful.

From an architectural point of view, the early Sanctuary was a very simple affair, consisting solely of a clearing in the dense woods enclosed by a wooden fence. Such a clearing, in Latin a lucus, produced a sacred space, a templurn. The cult was probably focused on an altar within the enclosure, but this has not yet been found. In 1885 Lord Savile excavated what was probably the earliest monumental building in the Sanctuary, the so-called Temple KKK (Figs. 2, 3). Judging by the building technique and the architectural terracottas associated with the temple, it was constructed around 300 BC.

Approximately 200 years later, at the end of the 2nd century BC, the Sanctuary underwent complete rebuilding. It was now arranged on a series of artificial terraces constructed entirely in Roman concrete as a means of creating a sacred architectural landscape. This rebuilding was part of a common trend in the late Hellenistic and late Republican period, and similar major renovations took place at other sanctuaries in central Italy, for example, Palestrina and Tivoli (Coarelli 1987). A new temple, of a curious and uncommon design according to the Augustan architect Vitruvius (4.8.4), probably crowned the upper terrace of the Sanctuary. On the central terrace, the renovated and redecorated old temple was now framed by a huge three-winged portico (see Fig. 1). At the same time or slightly later, further buildings that combined sacred and secular functions were added, including a small theater and a baths building. Additional shrines were also constructed to house other deities introduced to the Sanctuary, particularly the Egyptian goddesses Isis and Bubastis. By the end of the Republican period the overall architectural framework of the Sanctuary was complete, and during the subsequent Imperial period the building activity consisted mainly of renovation and repair.

The use of the Sanctuary came to a sudden end probably some time during the second half of the 2nd century AD. The Alban Hills are located in a zone of seismic activity, and an earthquake followed by an immense landslide covered the Sanctuary under many thousands of cubic meters of soil. This has proved fortunate for posterity, as the natural catastrophe sealed a variety of objects in their original context. Although the area has been exposed to centuries of despoliation in the quest for objets d’art, enough is preserved to give us valuable insight into the architecture and functions of one of the most important Italian sanctuaries and its cult.

The Cult of the Immitigable Diana

Museum Object Number: MS3483

Diana was the main deity of the area, and the forest as well as the lake was named after her. Traditionally, she is perceived mainly as the protectress of the hunt and of wildlife. However, combining ancient literary and archaeological sources, it can be seen that Diana, particularly at Nemi, had much more far-reaching powers, including those over childbirth, sickness, and health, and she could influence destiny and also predict the future. One of her cult names at Nemi, Trivia, as well as some of her three-bodied manifestations reflects these varied spheres of influence. Moreover, as we can see from literary sources, a living tradition rooted at least in the early Imperial period regarded the cult of Diana Nemorensis as a direct offshoot of the Taurean or Scythian Artemis Tauropolos (Graf 1979). This fierce goddess, whose sanctuary was located in the Crimea, demanded human sacrifices. It is probable that the Romans applied the myth of Artemis Tauropolos to the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis to explain an otherwise inexplicable bloody ritual in that Sanctuary, most probably the ritual killing of the ruling priest, the rex Nemorensis mentioned above. There is unfortunately no archaeological evidence at the site for this strange priesthood.

Thousands of votives—offerings to the goddess—unearthed in the Sanctuary testify vividly to the normal cult practice in the sacred Crove. These were manufactured mainly in terracotta and bronze, which remained the standard materials for votives until the late 2nd century BC. As part of the Hellenization of Italy during the 2nd century BC, marble gradually became more commonly used for voives and was standard by the Imperial period.

Mrs. Drexel’s Donation

The collection of sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis that Frothingham secured for the University Museum consists of 45 pieces (MS3446MS3484, MS4034-4038, and MS 6012a, b). At the beginning of this century, the provenience of the sculptures was questioned, first by E. Hall and later by S.B. Luce, the curators of the Museum’s Mediterranean Section during the first two decades of the 20th century (Hall 1914:121; Luce 1921:169, 176). In the old inventory of the Mediterranean Section, written years after the objects entered the Museum, the provenience of the pieces is given as “Lake Nemi.” Hall accordingly proposed that the sculptures may have come from “some of the lake-side villas.”

There can, however, be no doubt that the Nemi sculptures were actually unearthed in the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis. Some of the objects, particularly a set of marble vases most of which went to Philadelphia, were mentioned and illustrated in a report published in Notizie degli Scavi (Borsari 1895) soon after they were unearthed. In the same report mention is made, though without illustrations, of a number of marble statuettes found in the same room in the central portico of the main terrace as the vases (possibly room F). The description of these statuettes corresponds with the marbles in the University Museum, as do their type, style, technique, and iconography with other finds from the site. It therefore seems likely that the sculptural ensemble found in that room was divided between Frothingham and the Danish brewer Jacobsen. Jacobsen bought two marble amphoras and a large female head, identified as the head of a cult statue representing Diana, for the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen in 1896, while the accompanying pieces went to Philadelphia.

Museum Object Number: MS3484

Museum Object Number: MS3479

Museum Object Number: MS3452

Museum Object Number: MS3475

Museum Object Number: MS3457

Museum Object Number: MS3474

The 45 pieces of sculpture from Nemi presented by Mrs. Drexel to the University Museum illustrate the typological and chronological variety of sculptures unearthed in the Sanctuary proper. The marbles include fragments of one or more cult statues, votive statues and statuettes, a herm, a relief, votive marble vases, and several utilitarian marbles, such as architectural elements, parts of marble furniture, and stone weights (Moltesen 1997; Guldager Bilde and Moltesen 1998. See Figs. 5-16). The only category of finds not represented in Philadelphia consists of portraits of actors, local magistrates and their wives, and the Imperial family. These can be admired in the museums in Copenhagen, Nottingham, and Rome.

Greek Masters and Roman Pupils

The Nemi marbles are a valuable witness to the exchange of techniques, types, and styles during the critical years of transformation of the Hellenistic world into the Roman. As the large collection of Philadelphia marbles mainly consists of early types, this ensemble contributes in particular to our understanding of the early period of marble sculpting in the central regions of Italy. In fact, it makes up the largest collection of late Republican sculpture in Hellenistic style from a known Italian context.

Before the marble quarries in northern Italy were opened up in the middle of the 1st century BC, marble had to be imported from the eastern Mediterranean. Marble was therefore regarded as a costly and hence prestigious material during the late Republican period. Almost all of the marble sculptures found in the Sanctuary were made using the piecing technique. This technique, particularly common in the late Hellenistic period (though it is also found earlier and later), was adopted in the early phase of marble sculpting in Italy. In piecing, limbs and even parts of limbs are made separately and joined to the torso of the figure which may in turn also consist of several individual pieces (and the marble may also be pieced before sculpting begins). The piecing technique enabled the sculptor to use the precious marble right down to the smallest piece. At the same time, it provided noticeable aesthetic advantages. The piecing technique utilized inner supports consisting of iron dowels, e.g., for protruding limbs, so it was possible to dispense with what otherwise would be optically dominating external supports, i.e., marble bridges.

Hellenistic styles in sculpture were also imitated in Italy; for example, the very elongated limbs of particularly the marble statuettes is a typical late Hellenistic mannerism. The “cousins” of many of the statuettes found at Nemi are thus to be found not in Italy, but in the eastern Mediterranean, particularly in the wealthy Greek islands of Rhodes, Cos, and Delos. If the finished marbles are not to be considered straightforward imports, which is hardly likely given the large number present

at Nevi, it suggests that Greek sculptors—or Greek-trained local sculptors—worked at Nemi or in the vicinity.

A Roman Villa?

We have little or no idea of how the statuettes were displayed in the Sanctuary. Room F, where many of the statuettes were found, was hardly their original place of display but rather a secondary storeroom, as can be seen from the highly mixed character of the finds there. Many votive statues and statuettes exhibit marks of weathering on their marble surfaces and probably stood in the open. Some were displayed within an architectural frame, e.g., the statues found in the debris of the Sanctuary’s theater stage building, now in Rome’s National Museum; others probably adorned fountains and similar structures. It is also conceivable that the votives thronged the steps of the temples and the porticos.

As already mentioned, the varied Drexel donation of marble sculptures is not only of utmost importance to our understanding of Italian marble production in the late Republican period, but also of significance for our comprehension of life in the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis. Moreover, the general character of the marbles unearthed in the Sanctuary highlights the intricate relationship between the adornment of the public sacred space and the private secular space. In both spheres we find the same combination of cult statues—including representations not only of Diana, in the present case the main deity of the site, but also of Dionysos and his entourage, and of Venus and Erotes—with marble vases, decorative reliefs, and candelabras.

This coincidence has prompted some scholars to suggest that the Sanctuary was incorporated into a private villa. But this is to put the cart before the horse.

Surely, a sanctuary did not imitate the embellishment of a Roman garden but vice versa. However, the parallels from domestic contexts are much better known than from sanctuaries, so the reasons for interpreting the finds this way are obvious. The evidence from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis is therefore particularly valuable in that it is one of the few Italian sanctuaries from which so many marble sculptures have been preserved. Through the finds kept in the University Museum and elsewhere we thus have the rare opportunity to glimpse a world which is otherwise :known primarily from literary sources and from sacro. idyllic-wall paintings.

Epilogue

It is just over 100 years since the Nemi marbles reached the University Museum. In 1898 Frothingham was no longer attached to the Museum, and no more marbles were bought from Nemi. Jacobsen acquired a few more marbles at an auction in the Roman Palazzo Savelli the same year, which may have come from Nemi.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Nemi Castle became the property of the Ruspoli family. At the same time, new and strict regulations concerning antiquities were issued by the State. This finally ended the despoliation and hence destruction of the ancient sites, at least on paper. The Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis, thus, no longer supplied the market with valuable objets d’art. Instead, the finds made throughout the main part of this century were transferred to Rome’s National Museum, the Museo Belle Terme. It is presently the ambition of the Archaeological Superintendency of Lazio that the objects from the Sanctuary in Italian custody, along with the finds made during the recent excavations, be transferred to the museum built during World War II beside Lake Nemi to house the ships of the lake. This museum, dedicated to the archaeology of the Sanctuary and its surroundings, is to reopen soon.

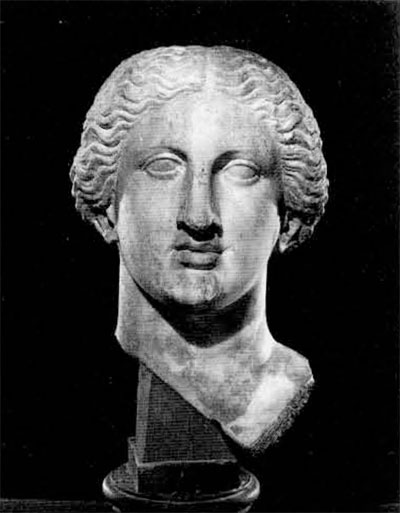

Cult Statues

At the time when the Sanctuary underwent its complete renewal at the end of the 2nd century BC, the shrines in the Sanctuary were also enriched with new cult statues. Luckily, remains of several of these statues have been identified. Best known is the colossal head of Diana in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and the life-sized male bust of Asclepius Virbius in Nottingham (Guldager Bilde 1996, with references). Both of these were constructed using the acrolithic technique, where only parts with exposed “skin,” such as the face, arms, and feet, are carved in marble, while the body itself consists of a skeleton of wood or metal clad in a garment of cloth or of sheet metal. This technique not only economizes on the costly marble, it also recalls earlier cult images in the chryselephantine technique that combined gold and ivory in the same way.

In the storerooms of the University Museum resides a larger-thanlife-sized female head, made in the same technique and of approximately the same date as the two mentioned above, that had until now escaped scholarly notice (Culdager Bilde 1996). The head probably belonged to yet another cult statue in the Sanctuary. A ledge cut in the hair above the forehead shows that originally the marble head was adorned with a diadem made in another material, probably bronze. The head is strongly classicizing, which is part of a common trend in the creation of late Hellenistic and late Republican cult statues. It does not copy a specific type, but it is related technically, typologically, and stylistically to other female heads of the same period.

The identification of the head is not easy. The matronly aspect does not necessarily exclude the possibility that the head portrays Diana herself, neither does the applied diadem which we know from other representations of the goddess.

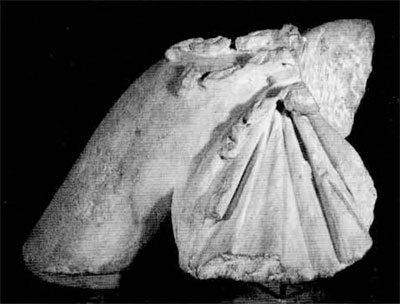

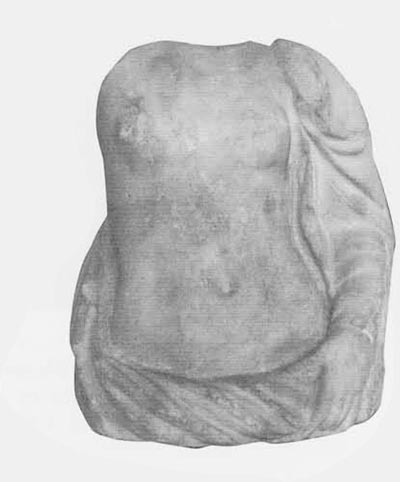

Diana Enthroned

A large fragment of an enthroned female deity, again larger than life size, derives from a statue made completely in marble but employing the piecing technique (Ny Carlsberg Rlyptotek 1997:92, fig. 63). A large part of the right shoulder, upper arm, and breast are preserved. The female figure is dressed in a sleeveless chiton, which exposes the right shoulder. Three meticulously shaped locks have escaped the coiffure and trail over the shoulder. There are some fragments in Nottingham of a hand, a lower right arm, two fragments of another arm, and a finger (Nottingham, Castle Museum N 610, 797-799, 803; unpublished) which may belong to this statue, as they are compatible with it in size, surface finish, and style. The right hand is stretched out with the palm upwards, suggesting that the statue originally held out an offering bowl, which would have been made in a different material, most likely bronze. The iconography is closely related to the representation of an enthroned Diana made in terracotta and probably the centerpiece of Temple late 2nd century BC gable. This figure is, unfortunately, only known from a 19th century photograph (Ny Carlsberg Rlyptotek 1997: fig. 65).

The style of the statue, the fleshy quality of the exposed body parts, the treatment of the hair and the drapery, as well as the marble technique itself are highly reminiscent of a group of classicistic statues produced in the second quarter of the 1st century BC.

Gifts to the Goddess

Apart from the evidence of the cult statues, a selection of marble votive statuettes in the likeness of Diana contributes further to our understanding of the goddess’s iconography in the Sanctuary. In Philadelphia there are fragments of three or more such statuettes (MS3453, MS3479 [shown], MS4034 and probably MS3477, MS3478). They are all of the same basic type, showing Diana as the goddess of the hunt clad in a short, sleeveless chiton. She wears hunting boots, and her cloak is tied around her waist and twisted into a bundle so as not to hamper her movements. From better preserved representations we can see that in her right hand she frequently held either a spear or a torch.

Frothingham’s Faun

To Frothingham a small statue of a faun was the “jewel of the lot,” and he particularly urged the Museum to buy it. In a letter to Stevenson he claimed that he had been assured by a certain “Sig. Pirani, who is an excellent practical judge” that “there is no restoration at all—merely the re-attaching of a few broken parts—nothing new” (UPMA; letter, Frothingharn to Stevenson, 26 October 1896). Frothingham was, however, deceived. The faun is a pastiche combining fragments of at least three statues, probably more. However, it is interesting evidence of the often skillful restoring practices of 19th century Rome.

The head is a masterpiece in its own right, sculpted in coarse-grained Thasian marble in a classicistic style. It shows a youthful faun with narrow eyes and a sensuous mouth. He wears a pine wreath with cones on his head.

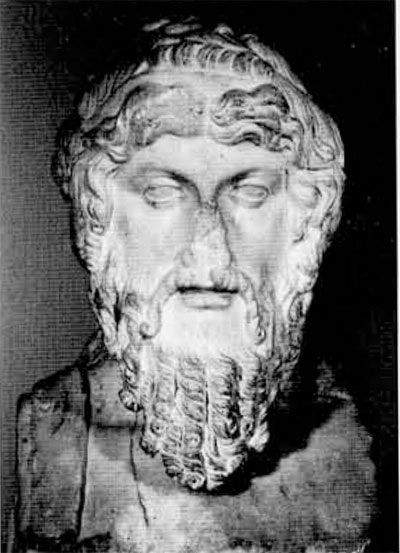

Dionysos

Most striking is the beautiful herm portraying Dionysos. (Herms were square pillars surmounted by the head of a divinity, originally Hermes; in the Roman period they were also used for portraits.) The face with its neat, almond-shaped eyes has a mask-like quality, and the long beard is arranged meticulously in parallel ornamental locks. The hair is wound casually around a broad fillet, and the ends of the fillet are folded with much care on each shoulder. This Perm is unique: there are no known replicas of it. It is eclectic in style, combining elements of different periods in a way that appealed highly to the Roman taste. It can probably be dated to the second half of the 1st century BC.

Chio’s Eight Mable Vases

Museum Object Number: MS3446

Museum Object Number: MS3447

Unquestionably the most impressive votive gift found in the Sanctuary is a series of eight marble vases. Two amphoras are in Ny Carlsberg Rlyptotek (inv. 1518, 1519); the remaining vases are in the University Museum (Borsari 1895:425-29; Guldager Bilde 1997). They each carry the same inscription cut into the shoulder of the vessel: Chio) d(onum) credit) “Chino gave this gift.”

Chin’s gift consisted of four amphoras and four griffin cauldrons, both types imitating old-fashioned Greek vases. The shape of the amphoras reflects the prize vases created for the Panathenaic games held in Athens every fourth year to celebrate the Athena Parthenos. Three of the Nemi imitation amphoras are decorated with scenes in relief unrelated to the Greek prototypes: a horse race between Eros and a satyr, a fight between two satyrs over the right to drink from a mixing bowl placed between them, and a pair of winged eagle griffins attacking a doe (Fig. 10). The fourth amphora is lacking any relief decoration, though it is possible that it originally had a painted design (Fig. 11).

The four cauldrons are produced in two pairs. They are all decorated with three griffin protomes springing from the shoulder of the vessel, and round the belly there is a cable ornament beneath which the vessel is vertically fluted (Figs. 12, 13). The cauldrons imitate Rreek wine-mixing bowls of particularly the 8th and 7th century BC, which were originally produced in bronze. The shape of the cauldrons and the character of the inscriptions indicate that the dedication took place in the late Augustan or early Tiberian period in the first quarter of the 1st century AD. However, technically, typologically, and stylistically the amphoras seem to be earlier, maybe by as much as 100 years. Thus, Chio may have bought four older vases and added his own four brand new cauldrons, or he may have renovated an existing monument.

All eight vases are solid, so there is no way they could have functioned as containers. Similar marble vessels, whether found in Greece or Italy, were exclusively used in a funerary context, either as grave markers or adorning the architecture of the grave (Guldager Bilde 1997). This begs the question of whether there was a tomb or perhaps a cenotaph in the Sanctuary. One of the Sanctuary’s main myths concerned the Greek hero Hippolytos, who was raised from the dead by Asciepios on the passionate entreaty of Artemis/Diana. In some of the Roman versions of the myth, after being brought back to life, Hippolytos was transferred to the Sanctuary by Lake Nemi as a minor god reigning at Diana’s side (Graf 1979). Hippolytos had a tomb in other sanctuaries, in Athens and at Troizen in southern Creece. He may have had one at Nemi, too, that was embellished with the eight marble vases. However, this remains a hypothesis that can only be verified by further excavation.

Even less is known about the dedicant, Chio, than about the way in which the vases were displayed; but from his name (which is Greek and does not fallow the formula for Roman free citizens) it can be seen that he was a freed slave, a libertils. He must have been a fairly prosperous freedman in order to provide this votive. Chio was not the only wealthy libertus to present Diana with handsome gifts. Particularly, several of the private portraits displayed in rooms in the central wing of the large three-winged portico were set up by this class of people, who played a significant role in the Roman society of the late Republic and the Imperial period.

Museum Object Number: MS3348

Museum Object Number: MS3450

Dancing Males

Museum Object Number: MS3456

There are a number of naked youths that are shown either leaning (MS3465, MS3481, MS3482) or dancing (MS3457, MS3466, MS4034, MS4036). Some of them could represent satyrs, Dionysos’s half-animal followers, although their tails are not shown; others may be Erotes (particularly the chubby MS3465). One is probably a hermaphrodite, as the brassiere(?) may indicate (MS3457, shown). The dancing figures in particular seem to be three-dimensional versions of figural types known from the more common two-dimensional representations in, for example, contemporary reliefs. The leaning boys, which cannot be readily identified, perpetuate types which have also been found among the slightly earlier terracotta statuettes unearthed in the Sanctuary (e.g., MacCormick and Blagg 1983:52).

Eros

The marble statuettes are neither copies nor variants of known types, but new, original creations. However, at least one replica of a known sculptural type is found in the Sanctuary. It copies the statue “Eros (un)stringing his Bow,” commonly attributed to the Greek sculptor Lysippos, the original of which is believed to have been dedicated in the Sanctuary of Eros at Thespiae in central Greece. Apart from this statuette, there were two other coexistent representations of Eros at Nemi (MS3473 and an unpublished statuette at Nottingham, N 607).

Venus of Female Deities

Statuettes of female deities other than Diana may also be noted in the collection. Only the one seen here can with some probability be identified as Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love—in Italy called Venus—a type known from other late Hellenistic representations.