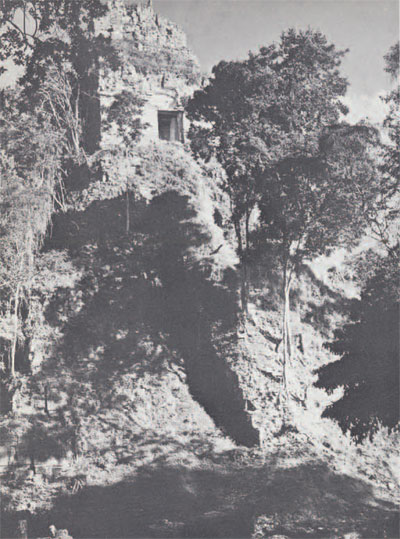

- Structure 78, one of Tikal’s unique four-stairwayed pyramids, was excavated and the nine sets of plain stone altars and stelae fronting the flat-topped building repaired and reset. Masons were brought in, a kiln for burning lime was built, and the difficult task, as shown here, of reconstructing one side of the pyramid was begun.

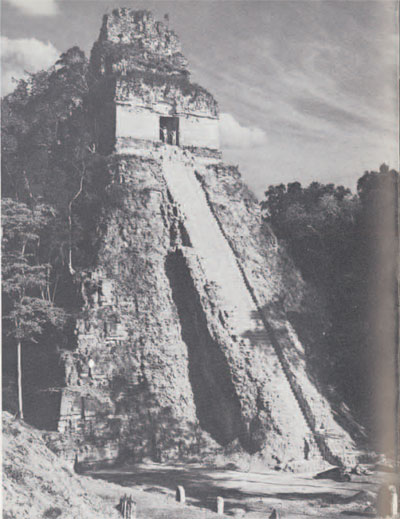

- The Temple Red Stela (center), scene of spactacular finds in the 1958 season, was deeply trenched on the temple’s center line, thus recovering the sequence of construction as well as ceramics to pin down its age.

- The “Inn of the Jungle” is in full operation with imple but comfortable accommodations for twenty-four persons. It serves as a base for many tourists whom frequent planes from Guatemala City bring to the site. Antonio Ortiz, manager of the inn, provides guide service throughout the ruins.

At this Maya site in northern tropical Guatemala the fourth season of field work under the direction of Edwin M. Shook continues. The Museum’s objectives, undertaken in collaboration with the Guatemala Government, are gradually being realized. Our initial difficulties with a dependable water supply have been solved. Excavations, laboratory work, reconstruction and consolidation, analysis of materials, and publication are proceeding in ways that we had hoped for by the time of the fourth season. Tikal as a tourist center has been an undoubted success. Yet, in spite of some contentment that things are going well, we remain awed by the problems of Maya civilization that we had hoped to solve and by the multitude of new problems that our excavations have quite unexpectedly presented to us.

Day after day we work among the bared temples and monuments, extending trenches, tunnels, and pits through floors and stairways, recording in notebooks and on film the often perplexing intricacies of construction, demolition, and rebuilding. The tens of thousands of potshreds and other objects recovered each season become laboratory objects, to be cataloged and studied. All of this work continues with the expectation that the time-sequence of related construction, artifacts, sculpture, and inscriptions, as well as site mapping and important studies of environment, will collectively produce answers

Some of our problems are narrow (“What bearing did plentiful flint deposits have on Tikal’s growth?”), while others are necessarily as broad as civilization itself. In Tikal we find the outstanding manifestation of Maya culture, a development recognized as a unique climax in the New World. Relatively isolated in the hot rain forest, off the main hemispheric artery, lowland Maya development and Tikal comprise an immense study problem of human evolution. Others long for Mars in order to find out what non-Earth evolution has been; we prefer to stay at Tikal to discover why and how American Indians accepted the challenge of the environment, to build through priest and farmer the remotely high-crested Tikal temples, to think in terms of five million Maya years, to go on growing perhaps two thousand years, and then to stop dead (in our limited view), leaving us the facts of sculpture and glyphs, potshreds, and stratigraphy, in endless notes and measurements.

Often while digging we find ourselves with some doubt that all our observations, the essential minutiae of excavation, will someday, by some mental gymnastic, fall into place. “Working hypotheses” are frequently found unworkable; preconceptions and certainties are all too often found to have been delusions. The critical floor, that by all rights should turn up at the stairway, is found to break off maddeningly well in front of it. At that moment, thoroughly discouraged, one tends to the conclusion that human behavior is really too complex to settle with pick, trowel, and shovel.

But the fact remains that some data inevitably do fall into place, providing perhaps only a fragmentary answer to a local problem. Previously discrete observations are found to relate and together they say something entirely new. What is found in excavation may have considerable intrinsic value as an object, but its truer value surely lies in its context and in the interpretative potential of that context. The honest happiness of discovery is all too often linked with apprehension: which problems does the discovery help to solve and what new problems will it raise in itself?

Discoveries and Reconstruction

Four more carved stelae were discovered. The Maya date on one (Stela 29) probably corresponds to A.D. 292, and is surely thirty-six years earlier than the oldest “contemporaneous” date previously known anywhere on Stela 9 at nearby Uaxactun. Three additional carved altars, two Early Classic and one Late Classic, were also uncovered, and it was determined that Altar 11, previously thought to be plain, is actually carved. Considerable evidence of fragmentation and resetting of monuments was recovered. Cached offerings were excavated from the center line of temples and from beneath stelae. Some caches contained hundreds of eccentric flints and obsidians along with human skeletal material, while others yielded sea shells, pigments of various colors, seaweed, sponge, and objects of flint and obsidian. A tiny mosaic mask (shown above) is one of the most remarkable objects ever found in the Americas. It and other mosaic pieces, once portions of an exotic figurine, occurred in a deeply hidden marine offering found in the Temple of the Red Stela. Also in the Temple of the Red Stela was a large Late Classic vaulted tomb which had been anciently looted. Above it, the remains of perhaps fifteen individuals were encountered. The basic sequence of ceramics and architecture was found in the Great Plaza and North Terrace. Aubrey Trik, project architect, is proceeding with the reconstruction of selected buildings.