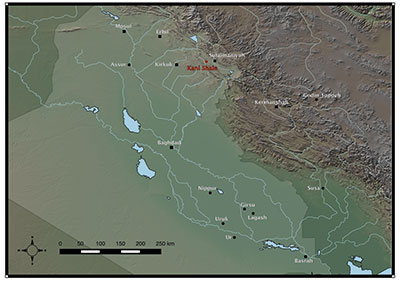

Within the imaginations of people inhabiting the dense cities that dotted the Mesopotamian plains, the Zagros Mountains to the east occupied an ambiguous role. On the one hand, they were the gateway to mythical lands of unimaginable wealth from where the sun god Utu/Shamash rose every day. On the other hand, it was an impenetrable land inhabited by barbarians “with human intelligence, but canine instincts and monkeys’ features” (according to the Babylonian myth “Curse of Agade”). The Mesopotamian plains o ered little more than fertile clay, while traders from the eastern highlands delivered boat and donkey loads of metals, colorful stones, and wood, as well as exotic animals and food. Although communication and exchange between Mesopotamia and the highlands extended back millennia before the first cuneiform texts, these interaction networks intensified significantly at the onset of the Bronze Age, the Age of Exchange. It is during this time, ca. 3500 BCE, that the seeds of our interconnected, highly urbanized world started to sprout. The Kani Shaie Archaeological Project (http:// kanishaie.org) explores a settlement along one of the trade routes between the Mesopotamian lowlands and the Iranian highlands that thrived during this crucial period of world history.

A New Excavation Project

While working in the Middle East has become increasingly challenging in recent years, the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq has been an island of relative security, political stability, and economic prosperity. In 2014, DAESH (also referred to as ISIS, ISIL, or IS) brought the violent turmoil of the past decade back to the borders of Kurdistan. Nevertheless, through their resilience, the Kurdish people withstood the pressure and their hospitality made the Kurdish region a safe haven for refugees from Syria and northern Iraq. Foreign archaeological teams work closely with the Kurdish authorities and contribute to the local economy through the employment of refugees, young Kurdish workers, and government officials who otherwise often do not get paid for months on end. The continued archaeological activities also provide a sense of normalcy and stability, while their results demonstrate the importance of the region in human history; this is a source of pride for people who have suffered a long series of brutal oppressions.

In 2013 and 2015, the Kani Shaie Archaeological Project (KSAP) conducted two seasons of excavations, with a third season scheduled for the fall of 2016. Our excavations have revealed that Kani Shaie was inhabited continuously for at least 2,000 years between 4500 and 2500 BCE. The first test excavations at Kani Shaie quickly revealed the site’s potential with the discovery of a wide range of painted ceramic sherds representative of different traditions from distant regions across Mesopotamia and Iran. The important discovery of a clay tablet with a seal impression and a numerical mark dating to the Late Uruk period (ca. 3500–3200 BCE)—the first of its kind to have been found in Iraqi Kurdistan—and other seal impressions from the subsequent Early Bronze Age further suggested that Kani Shaie was a local center whose inhabitants needed to keep track of their activities and exchanges. This long-lasting type of administrative technology was achieved by impressing wet clay with a seal containing carved images that communicated the identity of its owner. Slabs of wet clay applied on tied rope could seal off the content of containers or rooms, while a seal-impressed clay tablet guaranteed the authenticity of the document.

The Impenetrable Zargos Mountians

The Zagros Mountains, straddling the border between present-day Iraq and Iran, formed the interface through which much interaction and trade traversed. The high peaks of the Zagros stretch from northwest to southeast, significantly hindering travel. These mountains could only be crossed through a few east-west passes and with the help of people indigenous to the landscape. Today, the Zagros region encompasses Iraqi and Iranian Kurdistan, Luristan, and parts of the Persian heartland of Fars. Due to difficult political circumstances along with a scholarly focus on the major urban centers and empires of ancient Mesopotamia, the Zagros region is one of the least explored areas on the archaeological map. However, in recent years the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan has witnessed a tremendous boom of archaeological projects. Many of these projects explore the historical periods when the region was an important strategic focus of the Assyrian and Persian empires during the 1,500 years before the Muslim conquests in the 7th century CE. This area has always served as both an important route and a significant border between northern Mesopotamia and the mountains. In 881 BCE, Assurnasirpal of Assyria led his army against the land of Zamua, but had to fight his way through a wall that Nur-Adad, king of the land of Zamua, had constructed to block the passage of Babite, present-day Bazyan. This feat would be repeated by the Kurdish prince ‘Abd al-Rahman, Pasha of the Baban Emirate centered on Sulaimaniyah (or Slemani in Sorani Kurdish), in 1805 CE to stop the advancement of Ottoman troops.

The aim of KSAP is to explore the deep past of this crucial route through the Zagros Mountains. Interregional exchange of goods and ideas has had a central role in the development of Mesopotamian civilization. Our goal is to investigate how the intensification of interaction across the ancient Near East 5,000 years ago affected a settlement in the Zagros region at a time when the first cities and states grew in Mesopotamia. The highland communities inhabiting the eastern periphery of Mesopotamia facilitated interregional trade and played an important part in the history of the ancient Near East.

From Village to Local Center

Studies such as those by Mitchell Rothman on Tepe Gawra, located to the north of Kani Shaie, have shown that incipient social stratification and emerging hierarchies within small, prehistoric communities had already developed by the 5th millennium BCE. Likewise, evidence for administrative technology and centralized production strongly suggests that Kani Shaie, from its beginning, occupied a central place within the Bazyan Valley and perhaps served as a local focal point for processes of increased social organization beyond the household and even communal level.

The central place of Kani Shaie within the Bazyan Valley was fully exploited by the middle of the 4th mil- lennium BCE. The long, gradual development of the site was suddenly interrupted and the material culture of the settlement changed drastically to reflect typical southern Mesopotamian traditions. From the small sounding into these levels at our excavation, it appears that the site was remodeled into what may have been a forti ed and monumental enclosure. The radical shift to a foreign material culture suggests that Kani Shaie was perhaps taken over by a group of colonizers to control the flow of goods passing through the Zagros Mountains. The sealed numerical tablet shows the shipment of a group of horned animals, native to the mountains, traveling downstream on the river toward the Mesopotamian plains. Our current hypothesis, to be tested in future seasons of excavation, argues that Kani Shaie was a small node within the network of trade routes that facilitated the movement of goods through the Zagros Mountains, much like the network of smugglers that transport goods over the Iran-Iraq border today, a story recently covered by journalist Ania Bartkowiak.

Tracing the Orgins of Zargos Societies

By the end of the 4th millennium BCE, large-scale changes took place across western Asia with the abandonment of south Mesopotamian colonies and a return to regional cultural practices. The enclosure at Kani Shaie suffered destruction through conflagration, and a new settlement at the site consisted of small-scale architecture and housing units; again, we see a dramatic change in material culture. However, the settlement continued to fulfill a central role within the valley and maintained interaction with distant regions. The inhabitants of Kani Shaie shared cultural practices both with communities in northern Mesopotamia and in north-western Iran as reflected in the painted ceramics that dominate the assemblage of the site. In addition, ceramic types common in other parts of the Zagros Mountains and painted vessels typical of the region southeast of the Tigris River demonstrate that the community at Kani Shaie was plugged into a far-flung interaction network. These observations suggest that interregional interaction and exchange did not collapse at the end of the 4th millennium BCE as is often assumed, rather it continued unabated albeit through a very different organization that was no longer based on supra-regional cultural practices or restricted to elite enclaves separated from local communities. The excavations at Kani Shaie have, so far, retrieved several seal impressions from this period, impressed directly on large ceramic storage jars or on pieces of clay that were used to seal doors. Clearly there was a need to organize storage beyond the household level and a need to keep track of ownership.

The discovery at Kani Shaie of continued interregional interaction and the development of complex social organization is crucial for our understanding of the historical trajectory of the Zagros region. Archaeologists have focused on major developments and the origins of civilization in the extensive plains of Mesopotamia and urbanized sites in agricultural zones on the Iranian Plateau. The existence of organized societies and ethnic groups in the Zagros Mountains, as attested in later cuneiform documents, is usually attributed to secondary developments as a result of militarized interaction with powerful Mesopotamian polities in the later part of the 3rd millennium BCE. However, a reevaluation of existing data and new work in the region, such as KSAP, are slowly revealing a different picture of a long history of indigenous social and political organization.

By the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE, when this region appears for the first time in the cuneiform sources of Mesopotamia, Kani Shaie was abandoned. Larger regional centers emerged that attracted populations away from smaller settlements. During the following centuries the Bazyan Valley increasingly became a border zone caught in the conflict between expanding Mesopotamian kingdoms and highland polities.

History of Kurdish Village

The second chapter of Kani Shaie opened during the Middle Ages when the site became the focus of a small village in the 13th century and again in the 18th century CE, when the Bazyan Valley was part of the powerful Kurdish Baban emirate. While the village spread out northward from the ancient mound, the villagers buried their dead on top of it.

Our excavations are shedding light on another obscure episode in the history of the region, a history that is much more personal to the Kurds living there today. This became very clear when we exposed the grave of a young child that had been buried wearing a bracelet and necklace made of colorful beads that still have a name and meaning in the present-day cultural memory of the Kurdish tribal past.

Looking Toward the Future of Archaeology in Iraqi Kurdistan

With generous permission of the General and the Sulaimaniyah Directorate of Antiquities, respectively headed by Kak Abubakir Othman (Mala Awat) and Kak Kamal Rashid, we will continue the study of both the ancient and more recent history of the region through excavations at Kani Shaie. Archaeological research in the Kurdish region of Iraq is largely taking place in a spirit of collaboration and communication. In a few years, our understanding of the history and developments in western Asia will undoubtedly have deepened immensely with the addition of information retrieved through our archaeological work in this hitherto unexplored mountainous region.

STEVE RENETTE is a Kolb Junior Fellow and a Ph.D. candidate in Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World at the University of Pennsylvania.

For Further Reading

Rothman, M.S. Tepe Gawra. The Evolution of a Small, Prehistoric Center in Northern Iraq. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2001.

Van Bruinessen, M. Agha, Shaikh and State. The Social and Political Structures of Kurdistan. London and New Jersey: Zed Books Ltd, 1992.