As the exhibition Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs travels around the United States before opening at Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute in February 2007, the story of the first U.S. tour of the world’s most famous archaeological discovery provides a fascinating comparison.

In 1961 the planned construction of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt threatened to flood a number of major archaeological sites, including Philae and Abu Simbel. To save them, archaeologists and other interested groups began a worldwide effort to raise money and awareness. At the time, Froelich Rainey, the Museum’s Director, was also serving as President of the American Association of Museums. In his dual capacity, Rainey became a major force in educating the public about the Egyptian salvage project and in raising massive amounts of money to pay for it. He convinced the Egyptian government to send a selection of objects from King Tut’s tomb to tour museums throughout the U.S. for the first time since their discovery by Howard Carter in 1922. By including the Penn Museum on its itinerary, the exhibition would also become the perfect event to mark the Museum’s 75th anniversary in 1962.

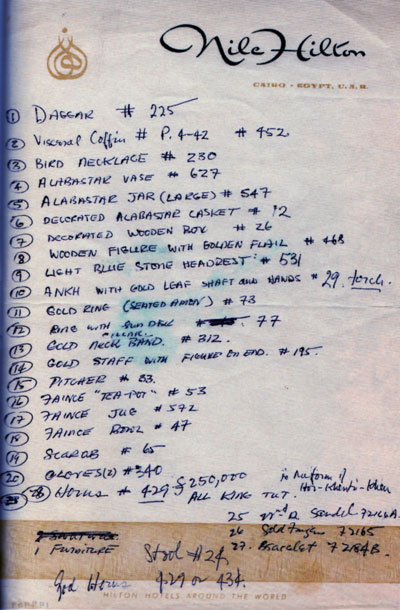

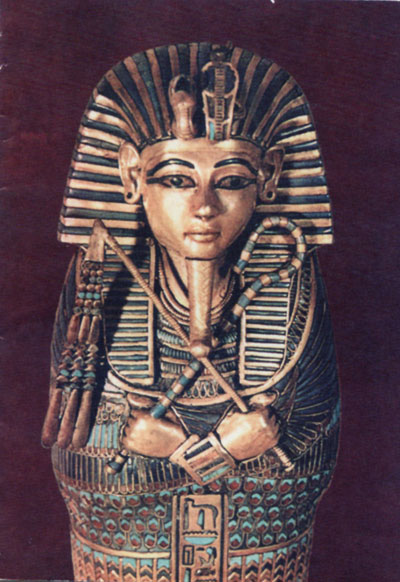

The traveling exhibition consisted of 34 small but fine objects, many of them connected directly with Tutankhamun’s mummy. These included a gold dagger and embossed sheath, the flail and crook made of gold and blue glass, and a miniature mummy case—an exact replica of the larger sarcophagus—that held the king’s internal organs. Other pieces of gold, much of it inlaid with lapis lazuli and other gems, as well as jewelry and carved and inlaid alabaster objects completed the show.

A two-year tour was planned, making stops at 17 museums across the U.S., beginning at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where it would be inaugurated by the first lady, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. The exhibition would open next at the Penn Museum.

The logistics of organizing the exhibition were not easy. Haggling over which artifacts to include, securing the participation of other museums on such short notice—everything was organized in one year—and cutting through international red tape made the arrangements a tense affair. The show was actually cancelled early in 1961 due to the prohibitive cost of insurance and later almost cancelled again when the respective government bureaucracies were unable to agree on the wording of the contract. Some also wondered how much sway the name of Tutankhamun still held over the popular imagination 40 years after the discovery.

We may never know the full story of how the tour came to fruition. As Rainey wrote in a letter to the Director of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund (which helped defray insurance costs): “I think you will be glad to know that after incredible difficulties, caused by the Department of State and the Egyptian Government, the Tutankhamun exhibition has finally arrived in Washington. Some time I would enjoy telling you the fantastic story of this maneuver, much of it strictly confidential.”

Not until the day of the opening was Rainey able to appreciate what he had accomplished. Speaking to a reporter, he confided, “I held my breath until the very last minute.”

The show, Tutankhamun Treasures, was a remarkable success, both for the Museum (where lines of visitors extended for several city blocks) and for the Egyptian salvage operations. Rainey wrote in his autobiography, Reflections of a Digger, “The combination of the President’s wife, the fame of Tutankhamen, Ahmed’s enthusiastic vitality [Ahmed Fakhry was Professor of History at Cairo University], and the controversial high dam itself, certainly caught on with the American public.” As a result, the U.S. Congress appropriated funds for the salvage effort.

Among Froelich Rainey’s many achievements as Director of the Museum (1947–76), his genius for public relations and his flair for original solutions rarely came together as brilliantly as at this time. Successfully marshaling resources all the way to the highest levels of government, Rainey realized his vision of bringing the world’s most famous archaeological discovery to the U.S., while simultaneously helping to preserve some of the world’s greatest and unique monuments.