One of the most difficult problems that Native Americans face is the lack of public knowledge about Native American legal and political status. Most Americans know about Indian treaties, but do not realize that treaties are made between nations and that Indian tribes are sovereign nations. They do not understand that these treaties are not ancient history, but the law of the land today, and that Indian tribes are sovereign governments. The United States is made up of the federal government, state governments, and tribal governments—three sovereign entities. The U.S. Supreme Court has acknowledged that the tribal governments are the oldest sovereigns on the continent—Native American sovereignty predates the sovereignty of the United States.

After first contact between European nations and Native nations (Indian tribes), the Europeans eventually came to realize that the tribes were nations, if for no other reason than they had the power to make war. The conflicts between European nations and Native nations were often settled through negotiations and treaties—agreements between sovereign nations. This common practice was recognized in the United States Constitution in 1787. Congress was given the power to deal with various sovereign governments: foreign nations, the states, and Indian tribes.

The Native American Rights Fund

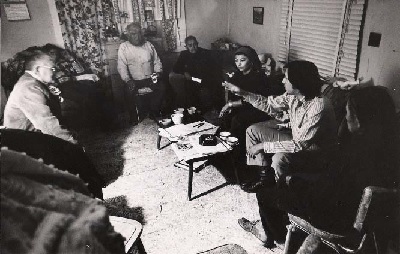

The Native American Rights Fund (NARF), the national Indian legal defense fund, was established in 1970, when tribal leaders and lawyers recognized the need to start a national Indian legal organization that could take on the most important legal fights for Indian rights. NARF was organized with the financial support of the Ford Foundation, which had been active in starting legal defense funds for other minority groups during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. For Indian people, asserting their civil rights meant asserting their Indian treaty rights and other Indian rights under federal law.

NARF grew out of the Indian legal services programs that had started in the 1960s as part of the war on poverty administered by the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). One of the most important programs of OEO was the creation of legal services programs across the country to provide, for the first time, legal representation for poor people in civil matters. Some of these legal services programs had begun on Indian reservations; the young Indian legal services lawyers had to learn about the obscure field of federal Indian law in order to represent their Indian clients. They discovered that Indians had substantial rights under the treaties, rights that needed to be asserted.

The protection and assertion of tribal sovereignty was NARF’s top priority as it began handling cases in areas of Indian country not served by the Indian legal services programs. One of the first cases it undertook was representation of the Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin, a terminated tribe. Under termination, the once-flourishing Menominee was gradually losing its land because it could not pay state land taxes. Tribal members were also being added to the welfare rolls. Congress told the tribe that termination would be beneficial, but that was clearly not happening. With the assistance of NARF, the Menominee Tribe went to Congress and asked them to repeal the Menominee termination law and restore the recognition of the Menominee Tribe. To the credit of the Congress, they listened and realized they had made a mistake. Congress passed the Menominee Restoration Act in 1973. The Act served as precedent for virtually all of the other terminated tribes, who had the same dismal experience as the Menominee, and Congress eventually reversed their terminations and restored them. Although many issues remain to be resolved, several important tribal sovereignty concerns have been addressed since 1970 with the help of NARF and other Native American rights groups.

Fishing Rights

The on-going vitality of Indian treaties was illustrated in another major case that NARF undertook in 1970. The tribes in the Puget Sound area of western Washington State negotiated treaties with the United States in the 1850s, taking into account the salmon runs which were the basis of the tribal economies, culture, and religion. In the treaties, the tribes retained the right to fish at their usual and accustomed places in common with citizens of the state. The state of Washington interpreted the treaty language to mean that Indians had to get fishing licenses and abide by state law just like everyone else. The Indian tribes asserted that their understanding of the treaties was that the tribes were to share the fishery, which they had been controlling entirely, on an equal basis with state citizens. A federal court in Washington State held that the tribes were entitled to 50% of the fishery and as sovereign governments had co-management regulatory authority with the state of Washington over the fishery. That decision was affirmed by a federal appeals court and later by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1979.

Eastern Tribal Land Claims

NARF undertook representation of several tribes in the eastern United States in a series of land claims lawsuits based on the 1790 Nonintercourse Act, one of the first Indian laws passed by Congress. That Act invalidated any land transactions with Indians that were not approved by the federal government. For some reason, many of the original 13 states in the Union did not believe that the law applied to Indians in their state and proceeded with land transactions with Indian tribes without federal approval.

The lead case was brought on behalf of the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot Tribes in Maine who sought to invalidate past land transactions that Maine had made with the tribes. Lower federal courts held that the tribes were Indians covered by the 1790 Nonintercourse Act and that the state’s land transactions with the tribes were illegal. In 1980, before the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, a settlement was reached and approved by Congress that provided for federal recognition of the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot Tribes. Over 300,000 acres of land were bought for the tribes from willing sellers with over $81.5 million in settlement funds provided by the federal government. Similar settlements for other eastern tribes followed.

Gaming

Perhaps the most important tribal sovereignty case of the modern era was handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1987. It involved an attempt by the state of California to regulate a gaming operation started by the Cabazon Band of Mission Indians. The Supreme Court held that the state of California had no authority to regulate gaming on Indian lands and that gaming was a matter of federal and tribal law. NARF had filed a friend of the court brief in the case on behalf of several tribes in support of the Cabazon Band.

Tribes had become involved in gaming as a way to generate tribal governmental revenues, and to provide tribal governmental services to their members in much the same way that states involved in gaming generated state governmental revenues to provide state services to their citizens. After the Cabazon decision, states sought to have Congress limit the effects of that decision, and in 1988 Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. In a compromise, Congress affirmed the sovereign right of tribes to raise tribal government revenues through gaming. For casino gaming, however, tribes were required to negotiate government-to-government compacts with states that would allow the states some regulatory authority over tribal gaming.

The Tribal Supreme Court Project

Favorable U.S. Supreme Court decisions in Indian cases supported the Indian self-determination and tribal sovereignty movement from 1970, when NARF came on the scene, until the 1990s when the makeup of the justices on the Supreme Court began to change and tribes found it increasingly difficult to win cases before that Court. This dramatic change became very clear to tribes in 2001 when they lost several important tribal sovereignty cases in the Supreme Court that they thought they should have won. Tribal leaders called a special meeting to address this crisis and formed the Tribal Supreme Court Project. The Project formally coordinates the efforts of tribal leaders, tribal attorneys, law professors, and Supreme Court practitioners on Indian cases headed to the Supreme Court in an attempt to put forward better legal briefs and arguments that will be accepted by the more conservative Supreme Court. The Project is coordinated by the National Congress of American Indians and NARF and has had limited success thus far in changing the win-loss record of tribes in the Supreme Court.

The Continued Struggle to Hold onto Native Lands

In 2009, a major setback for Native tribes occurred in the Supreme Court in a case involving the Narragansett Tribe and the state of Rhode Island. The tribe sought to have land that it had acquired placed into federal trust status for the tribe under the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, which authorized such a procedure to help tribes rebuild their land bases. Land placed in trust status is no longer subject to state jurisdiction but comes under tribal and federal jurisdiction. The state of Rhode Island objected and asserted in court that the 1934 land-into-trust provision only applied to tribes under federal jurisdiction in 1934 and not to the Narragansett Tribe, which received federal tribal recognition in 1978. The Tribal Supreme Court Project became involved in the case and helped the tribe prevail in the lower courts. Although the federal government had been taking land into trust for all federally recognized tribes for over 70 years under the 1934 law, when the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, a majority of the justices held that the 1934 law only applied to tribes under federal jurisdiction in 1934.

This decision has created two classes of tribes: those able to rebuild their tribal land bases with land taken into federal trust status, and those who cannot. Since the decision has a major economic impact on those tribes unable to have land taken into trust status, tribes have sought to have Congress pass a law making it clear that all tribes are entitled to the rights in this regard. Thus far the tribes have not been successful in getting Congress to pass such a law, but their efforts continue.

Protecting Native Women Against Violent Crime

In another major effort in Congress, tribes are currently seeking federal legislation that would protect Native American women from violent crimes that occur too often in Indian country. The high rate of violent crimes against Native American women committed by non-Indian men is the result of the criminal jurisdiction laws that fail to protect them. The federal government has felony jurisdiction over non-Indian men, but for various reasons prosecutes very few of them for these crimes. The states have misdemeanor jurisdiction over the non-Indian men but also prosecute very few non-Indian men. The tribes have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians according to a 1978 U.S. Supreme Court decision. This lead to a jurisdictional void that tribes successfully filled by having Congress authorize tribal criminal jurisdiction over non- Indian men for crimes against Native American women as part of the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act passed by Congress in 2013.

Protecting Indian Children

At the present time, tribes have great concern over a case recently decided in the U.S. Supreme Court involving the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. This law was passed to stop the large number of Indian children from being taken by state agencies and adopted by non-Indians. Tribes were losing tribal members and their futures through this process. The Indian Child Welfare Act established a placement preference for Indian families, gave the tribal courts jurisdiction over these placements no matter where the children were located, and allowed the tribes to intervene in the proceedings to protect their tribal members. The case recently decided by the Supreme Court involved a non-Indian couple trying to adopt an Indian child without complying with the Indian Child Welfare Act. In an interpretation of the Act of great concern to tribes, the Supreme Court held that the Act did not apply to the facts of the case and allowed the adoption proceedings to continue.

Rights of Indigenous Peoples around the World

Tribes have recently received great assistance from the United Nations in their fight to maintain their existence as sovereign nations. In 2007, after a 30-year effort by indigenous peoples around the world, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Declaration recognizes the rights of these people to self-determination, their traditional lands, and their cultures and religions. It is an aspirational document that all of the nations of the world are called upon to honor. The United States voted against adoption of the Declaration in 2007, but President Obama endorsed the Declaration in 2010 at the urging of tribal leaders. It is hoped that additional arguments for the protection of tribal sovereignty and other tribal rights provided by the Declaration will help the tribes prevail in the United States judicial, legislative, and administrative forums. NARF represented the National Congress of American Indians for many years in the proceedings, leading to adoption of the Declaration and endorsement by the United States, and continues to be involved in the implementation of the Declaration.

For more information see: “A History of Government Policies“