In Latin America there never has been a real, total cultural fusion such as occurred in Europe where the Mediterranean basin with its firmly structured culture and demographic conditions has, for millennia, received waves of Asiatic migrants.

On the contrary, in the New World Iberian culture was superimposed by aggression on the pre-Columbian cultures. Traditional societies of Latin America which for the most part had remarkable structured cultures of their own, suffered a cultural shock so great and so profound that it could almost be called a metaphysical trauma, even though on the surface there appeared signs of acculturation. One can see that a true spiritual fusion, a real integration capable of forming a “community of destinies and ideals” never occurred. Rather, we now see a marginalization relentlessly growing, deriving from the cultural and economic duality of those two antagonists who were first joined together in the sixteenth century and whose mutual differences have not yet been overcome,

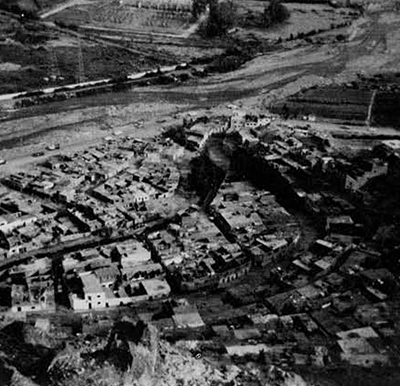

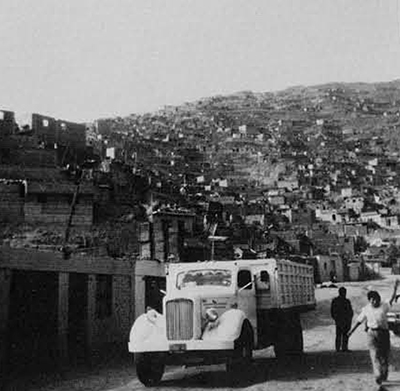

Peru, a nation in the process of acculturation since the Spanish conquest, in no way escapes this fundamental duality which lies at the root of the internal colonialism existing there today. During the past twenty years this Andean country has witnessed extraordinary urbanization-forced, disorganized, and anarchic. Between 1940 and 1957 the population of Lima tripled and then doubled by 1970. This growth does not derive from any national planning but finds its origin in the economic readjustments inherent in the capitalist structure of the country. It is this structure which determines the grafting onto the cities of numerous groups of people who burst onto the new urban scene bringing only the extreme poverty of their sterile fields and their traditional, indigenous culture. This undeveloped supply of Indian manpower, unqualified and without any real material resources, immediately runs up against an already over-extended administrative machinery, clogged by the earlier influx of unskilled migrant workers. The earlier migrant sector which already has a weak productivity sees itself invaded by this mass of people—people without work who, unable to produce, threaten to deform even more a system whose essential characteristics are found in inefficiency and resistance to change from traditional economies into modern industrial activities.

The over-burdened urban structures, unable to take in these invasions of peasants, allow them to accumulate on the fringe of stable economic, political or social areas. This process of “hyper-urbanization” is obviously not limited to Peru. It is found in all countries of Latin America under different names: “favelas” in Brazil, “callampas” in Chile, “ranchos” in Caracas, “cantegriles” in Montevideo, “villas miseries” in Buenos Aires, etc. As a matter of fact, these squatters’ villages are merely the most acute symptom of an economic structure which excludes the great part of its population from any authentic, active participation at its center, and in so doing deprives them of the opportunity to make a decent living.

Today it is estimated that internal migration in Peru has reached the proportion of a chronic national catastrophe. It brings rural marginality into the urban context where it is intensified, straining the urban situation to the limit while agrarian problems continue to get worse despite the “revolutionary” agrarian reform of June, 1969.

Therefore we no longer merely see an opposition between the past and the present expressed with so much realism in the large cities of Peru. We are dealing with a real economic confrontation between those on the bottom and those on top, between those who waste and those who are totally deprived, between those who strain to climb out of their misery and those who effortlessly live in ease and abundance.

In this dramatic and unequal confrontation we find, on the ecological level, housing situations where an elegant, solitary building stands next to vast stretches of crowded squatters’ villages called barriadas.

By 1950 one could see that the first phase of growth was being followed by a second phase of organization. That is to say, the barriada was institutionalized little by little, being forced to promote its internal organization and obtain a rule by law to save it from extinction.

Numerous studies have treated the dysfunctional aspects of internal migration in Peru, but this is generally done with a technological concern. As Vekemans says, “One views the social with the vision of an economist, elaborated in a world foreign to ours, the Anglo-Saxon, with complete disdain for the individuals who form the core of such a social phenomenon and act within it.”

In a brief glimpse at this vast topic we present here two aspects of the problem: first, a descriptive study of the barrida in Peru; second, an analysis of the consequences of the rural exodus on the personality of the Peruvian migrant and its hidden effects.

What is a Barriada?

According to Matos Mar, the barriada is “a social agglomeration formed by a population coming together and which occupies empty lands, generally belonging to the State, social service administrations, the city, or individual owners who are not using them.” Now in the absence of a real policy of use (from which follow the fierce speculation on building sites, corruption, etc.) and given the total lack of public authority in the matter of housing, we can assert that “with the influx of migrants, the creation of the barriada seems to be the only solution.”

It must be acknowledged that the barriada is part of the city—even if it is found at its periphery. It remains nonetheless at the fringe of the urban center since the members who form the barriada are not integrated in the development of the city, in its progress, prospects, fears and decisions. The barriada is the city but it is also the final stage of the rural-urban continuum of marginality whose most characteristic trait is non-participation in national life.

These colonies, created outside the law on lands generally unsuitable for construction, are different enough despite their similarities to allow us to make a classification. We can distinguish three general types of squatters’ villages according to their degree of isolation and their relations with the city and among themselves.

The first type includes those barriadas which are totally autonomous from the first day of their existence, situated at the periphery or even at a distance from the city. They form satellite urban embryos well on the way to becoming independent centers with their own services. This is the case of Ciudad de Dios established in the desert of Atocongo, twenty-two kilometers south of Lima along the Pan American Highway.

A second type results from a geographic regrouping of several old barriadas. Thus the services existing in one can be used by those unprovided for in the other, and vice versa. Only some geographical feature prevents their total fusion (e.g. they are separated by a road or by the River Rimac which runs through Lima). This type is represented by the group San Cosme, El Agustino, organized into six barridas.

Finally there are the barriadas assimilated into the mother city, i.e. they are enveloped by the extension of the city (e.g., San Martin de Porres). Their internal organization is but an extension of the city’s services.

How Does a Barriada Come Into Being?

When these squatters’ villages first began to appear they could be successful only by an extensive seizure of property. Today, however, the initiative is taken by a handful of families without shelter who inaugurate a take-over. These families may come directly from the migratory regions of the sierra or they may have been driven out of their old slums in the city. From the moment they agree to act one observes a real collectivism founded on mutual desire for property and security. When the goal is attained and the development of the barriada becomes defined, this initial collectivism will diminish little by little and give way to an individualism strongly tinged with egotism.

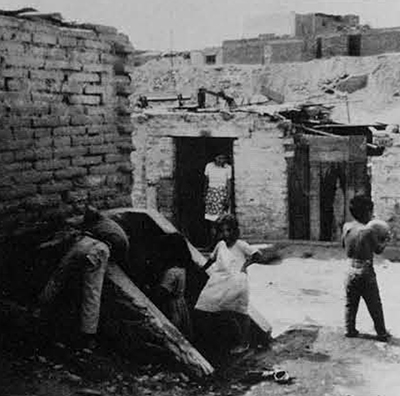

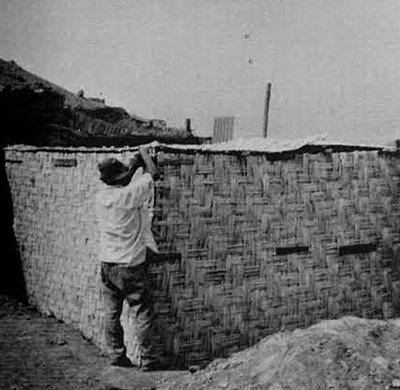

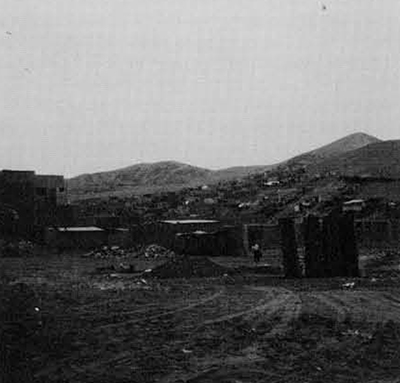

The tactics of the proposed seizure are generally kept secret by those who start the whole thing. Preparations are made with the greatest circumspection. The desired land is surveyed and then suddenly one morning squatters are found installed on land which was unoccupied the night before. They are there protected by cartons, rags, and temporary matting, flying the colors of the Republic of Peru and singing patriotic songs. The invading squatters await the representatives of the law, ready in every way to defend their first, illegally acquired wealth. Once installed on the desired land the native considers it his own and he looks for some material guarantee against the ever-present threat of expulsion. To him, building seems the most secure solution. This takes place in two stages.

First comes the provisional period which can last several years. During this time establishment of a house occurs in three steps.

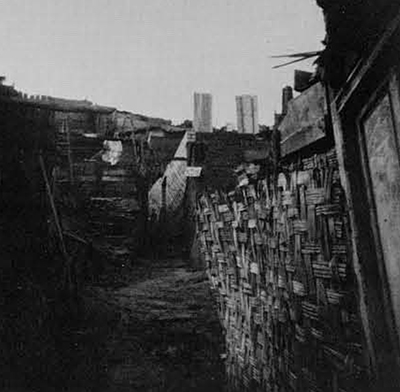

Huts rise like mushrooms the moment the take-over occurs. Their immediate function is to stand as a sign of ownership and only secondarily to serve as shelter. The materials used are those collected by scavenging (boards, cartons, tin, matting).

Next we have dwellings with walls of puddled clay and roofs made of reed, boards, or grass covered with mud.

And finally there are those structures which use dried earth for the three side walls and have the front wall of brick. Reeds covered with mud form the roof.

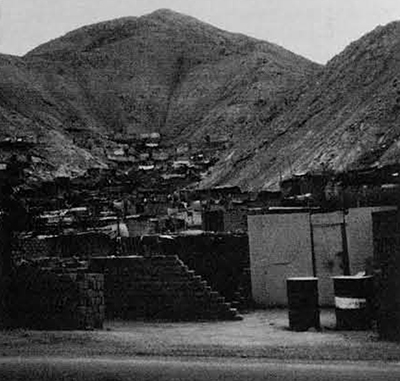

In the first barriadas the living quarters are made up of differing kinds of houses among which narrow, dirty passageways twist and follow an uneven route. They lead through an interminable and unsanitary maze of streets, the playground of the children of these South American ghettos.

Then comes the period of stability. At this time the “permanent” house appears with brick as the basic material. From time to time a coat of bright paint covers it, the windows have panes of glass and are even occasionally decorated with wrought iron. At this point everything indicates a change toward urban society: the maze-like plan of the squatters’ village yields to a desire for order and control in the location of residences. One can see that some barriadas form a grid, and others radiate from a well-constructed center. The plan and the provision of water, electricity and basic services give proof of real internal organization.

Whether they are the result of a spontaneous, unorganized act and are constructed imperceptibly, or spring up suddenly in a very carefully planned way, the barriadas will have as basic traits illegality and instability. But at the same time they reflect the mad hope of people who are totally deprived and who wish to extricate themselves from their present state. This is why settling and building assume a great importance when the migrants arrive. They see in these actions a means of adapting themselves, of entering into the ranks of the new society. The squatter’s house is the symbol of everything which the native does not yet have and which is indispensable to him: protection, intimacy, peace of mind. Despite its sordid appearance his but represents his sole assurance for the future. It is his own blessed space, “his corner of the world” which accepts him in a hostile land. The barriada is the refuge of those whom social inequalities have cast to the fringe of human life. Contrary to what has been occasionally written, the barriadas are not the sanctuary of delinquency, crime and prostitution any more than they represent a communist ferment. Every serious study in Peru has shown that the barriada is not a simple juxtaposition of individuals forced together. Rather, it presents a real organization expressed in all aspects of collective, affective, social life whose base is the family nucleus.

As opposed to the favelas of Rio, organized crime is practically non-existent in Peruvian squatters’ villages. This can be explained by the personality of the men who live there. Basically the Andean is an introvert, inclined to fatalism, who rarely gives expression to his desire for dispute. In contrast to the Aymara who is much more open and expansive, the Quechua Indian is meek, silent and extremely tranquil.

The barriada, then, is not to be explained merely as a particular kind of ghetto but as one that plays an important social role. It allows the recently arrived migrant to become gradually accustomed to the statuses and roles demanded by the modern urban center. His new relationships with others in the industrial community will no longer be based on personality but rather on efficiency. That is why the role and even the mere presence of the barriada is positive. It is situated halfway between the industrialized city and the traditional countryside. It makes it possible for the migrant to have a period of accommodation and adaptation, thanks to its transition structure which can offer a new group solidarity.

In the first moments of taking over some parcel of land, the settlers organize themselves into a defense committee against the latent hostility of the society which is taking them in. Later they form different associations which promulgate rules and regulations, assure the stability of the barriada and after innumerable proceedings obtain the property titles necessary for their security. Also, thebarriada is the place where provincial clubs, musical get-togethers and feast day celebrations for those who originally came from the same village take place.

In the initial period of settling, migrants do not show any disappointment. As yet, living in squatters’ villages presents nothing of a comedown—on the contrary it is a sign of a certain amount of progress. For the peasant is living in the city. In comparison with his Andean brothers who have stayed in their village in the cold and thankless Puna, the migrant has acquired a certain moral prestige. Later he wavers as he becomes more aware and realizes that his situation still lies far from any real participation in the urban economy, and as he finds himself a victim of the active non-participation which characterizes these problem areas.

Barriadas proliferate at a dangerous rate, but they carry with them alternatively the seeds of hope and despair and constitute the only haven of Indians driven from their ancestral lands. They are the places of native acculturation, the indispensable link between two economic systems, two cultures, two civilizations.

The settler, who was a campesino yesterday and tomorrow, if he is lucky, will be a sub-proletarian, feels that not only is living in the squatters’ village a means of settling down but that this is the place which protects the fragile, basic nucleus which is the family. It is in the squatters’ village that the hopes of becoming someone in a true, humanizing relationship will expand or disappear. Those dreams which he formed back up in his Andean community on the eve of his journey to the city will be realized or die here.

When a man decides to abandon his ancestral land in the Andes and the existential security of the tradition which his village offered him, this change presents not only an aspect of geographical mobility but one of socio-psychological mobility as well. The attraction urban society has exercised on him for a long time is now joined with the forces of expulsion from his own rural, traditional universe which is dying, poor, and incapable of helping him overcome his disastrous socio-economic situation, The question is posed urgently: “What can I do to better my life?” The solution is to migrate to the city, a place unknown but imagined as an accessible earthly paradise, a land of Canaan. Gradually the native who has never before left his village comes to imagine the city as the expression of the new millennium in an almost mystical vision which has nothing in common with reality. Thanks to this new faith which comes from his imagination, the native seeks release from his increasing frustration. Generally he begins by phantasizing. He invents and exaggerates in a way that corresponds to his desires. He attributes the role of new mother” to the city. He imagines that the city is waiting for him, ready to give him her affection, her protection, while in the rural world he still undergoes the ingratitude and attacks of the bad mother, or as Roger Bastide puts it, “his stepmother.”

Thus the migrant undertakes his journey. He leaves with bare feet and empty pockets, inspired with hope and an almost mystical energy. Will the city accept him? Will he really find the help he expects in the Church, the Doctor, the School, the President? His dream derives from his frustrated personality discharged in imagination through the forming of a myth which can be ritualized. This dream is clothed with an aspect of possibility by the innumerable details and descriptions of the seasonal migrants on their return to the village, or equally from the transistor radio. Often the accounts of those who have gone to the city and returned add to the fabric of invention. The migrant who has failed in his urban plans and wants to hide his disillusionment, or wishes to add to his prestige, doesn’t hesitate to lie. For those who have never left the micro-culture of their village every storyteller assumes the status of one who is in the know, one who has made the pilgrimage to the city. Each word of the storyteller, whether it be true or false, stimulates the anxious minds of his hearers. As a result of such idealization, the disillusionment is traumatic when the native really finds himself confronted with the modern milieu of the urban center.

Very soon the self-exiled man discovers something totally different from what he had hoped. Each succeeding day he gains a sharper impression of a series of attacks on his happiness. He becomes painfully aware that his immediate reality does not correspond at all to what he had imagined back home on the high plateau. Since he does not find the necessary security near his new mother,” he feels with greater pain his spatial displacement from the old, corresponding to the first, affective rupture of the infant from its mother. This mobilization of primordial anxiety is much more serious than the original rupture, for now the abandonment of the protective being is formalized by all the administrative steps which the migrant must accomplish to have the right to stay, look for work, and live. These steps accentuate even more the cutting of the umbilical cord, the new rupture, the new estrangement vis-a-vis his mother. In the particular case of the migrant who comes from the Andean sierra this feeling is still more intense, for he was living before in an almost mystical communion with Pachama, the earth, his mother.

To this psychoanalytic factor of transplantation is added another of a cultural order.

The new modern world is no longer considered by its differences with the traditional world but by its contradictions. The settler now becomes the victim of a confusing conflict between his basic personality and the new milieu of the society which takes him in. He has urban aspirations and yet a rural inheritance from the Quechua cultural patterns. In his pueblo, the acts of the group or community were determined once and for all by proscriptions which prevented any free choice. His social status was determined. Now suddenly he finds himself obliged to choose and take individual responsibilities to adapt to the new frame of reference in the city. He must acquire a new status which will make him a member of a new society. From now on his basic criterion for action can no longer be that of conformity but of rationality.

The settler thus feels himself doubly possessed: identical to what he was before in his native community but at the same time different; old in one part of his being and new in another.

This duality arises because the individual, even one most capable of adapting his actions, thoughts and behavior to the models of the new society, cannot learn to feel the same reflexes as the urbanites. Each time he finds himself in a situation which demands a quick reaction or an immediate choice, his inability to find fixed points of reference disconcerts him. Like a magnet gone haywire, he is no longer able to direct himself.

Later this conflict, born of migration but manifested in the mind of the migrant, produces a state of alienation. Very often he cannot find a balance between his inner personality and the demands of the city. Consequently, he feels his marginality in a more acute way and slides quickly into despair.

Now, to the material poverty which he knew already on the high plateau is added a new poverty which comes from loneliness. The city hinders traditional solidarity, particularly in the beginnings of a barriada where only a defensive and temporary solidarity is established. The migrant is only a stranger who comes to settle down. And as Roger Ikor has written, “to be a stranger is to be alone, alone in the middle of a world which cannot be understood and in turn lacks understanding, where the guidelines most necessary for the mind to orient itself waver, blur or deceive, where the simplest gesture presents a problem and can give scandal, where the surest teachings of experience are struck down, where everything has to be relearned, where one feels naked, defenseless, exposed, ridiculous and a bit mad.”

The settler generally has no occasion to participate passively (consumption) or even actively in the centers of decision of the city which will literally as well as figuratively push him toward its fringes. So, slowly he gives way, conquered by the surrounding hostility and by his personal inability to penetrate the values of the modern world and make them his own. His previous attitude of “being ready” for the city has slowly been changed to “acceptance of being set aside.” And this exclusion will produce grave social and psychological disorders. Each day, individuals oscillate between the man who is disappearing and the man who has yet to be born, without really succeeding in being totally one or the other. When the Peruvian peasant arrives in the city he is condemned to live alone in two antagonistic societies and forced to become a marginal man in a marginal zone.

But the personality of the migrant in the barriada does not derive from an individual failure of adaptation or innate predisposition. His conflicting personality is a social product. Marginal man in the city becomes such through a process of acculturation which affects him. It is the historical nature of the relationship between the city (modern) and the country (colonized hinterland) which is responsible for the appearance of these disintegrated personalities—atomized as subjects and transformed into units of consumption or study the men of the squatters’ villages.