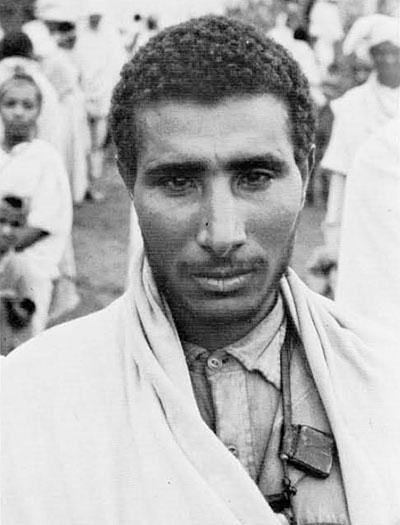

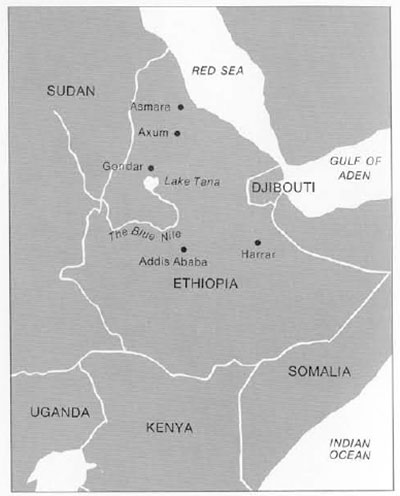

The Amhara are the politically dominant people of modern Ethiopia. Agriculturalists of the northern highlands, they are the descendants of an indigenous Hamitic people, whose culture and physical appearance became strongly Semiticized by numerous invasions from south Arabia. A second important influence in the development of Amhara culture was heralded by the introduction of Christianity during the fourth century. These first missionaries were men from the eastern Mediterranean and, after the great schism announced at Chalcedon, the Ethiopian Church continued its ties with the Orthodox faction, as a dependency of the Coptic See of Alexandria. The success of Islam, sweeping across Egypt and Nubia, severely limited contact between the Abyssinian highland and the rest of Christendom. In consequence, the development of the Ethiopian Coptic Church, and, ultimately, its relationship to Amhara culture has been more substantially influenced by autochthonous forces than would otherwise have been the case.

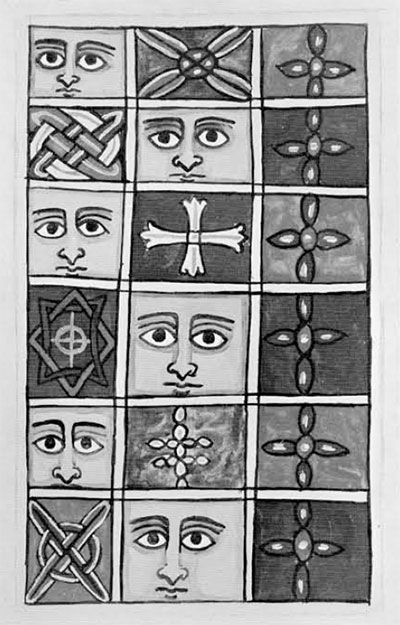

The influence of the Church is nowhere more apparent than in a review of Amhara art. The Amhara have no concept which approximates “art” as it is used in English, and each of the varieties of Amhara graphic art—Church paintings, occult drawing, and tattooing—is considered discrete, a distinctive instrument to achieve particular ends. Painting, for example, is largely didactic, depicting biblical scenes and personages, episodes from the lives of the saints and the history of the Church. In a style of obvious Byzantine affinity, the painter sets these motifs in contiguous panels upon the muslin-faced walls and ceilings of highland churches.

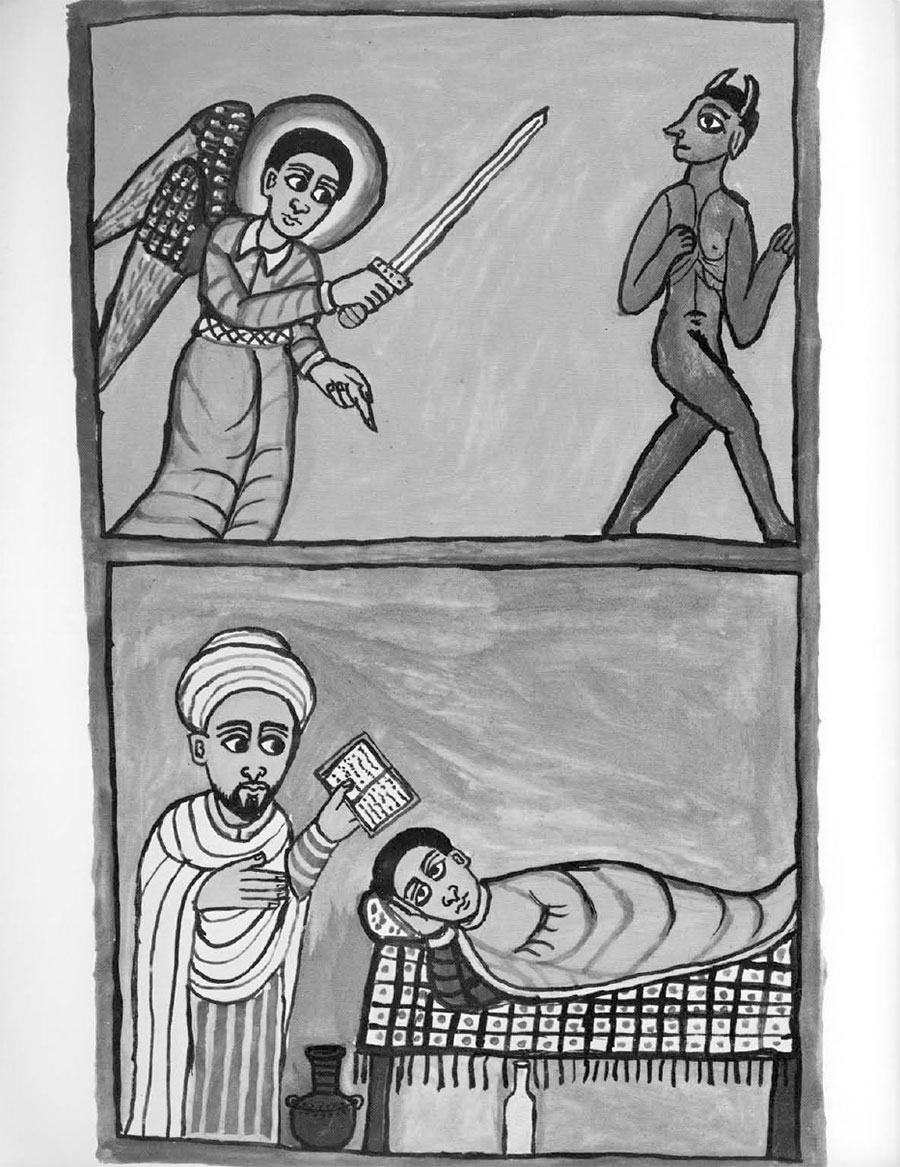

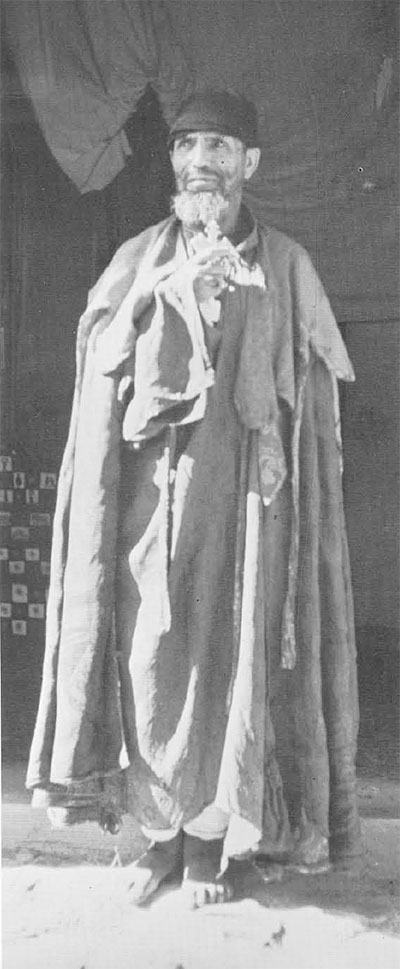

The occult drawing is known in Amharic as telsem (cognate of the English “talisman”) and differs radically from the church painting in form, intent, and production. Ethiopian talismans, sewn into a leather amulet together with the appropriate herbal ingredients, are worn to ward off the numerous satans, persecutors of man and foes of the Church, who live in the forests, lakes, and rivers of the countryside and in the hearth ashes and beer dregs of the home. Both the church painter and talisman drawer are ecclesiastics, since a religious education is the sole means of acquiring the literacy and special knowledge required by these endeavors. Indeed, the paintings and drawings accompanying this article are the work of a single individual who lives in Gondar town (about thirty miles north of Lake Tana), national capital during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. He is the latest of a series of artists who have engaged in replacing church paintings which were destroyed during the nineteenth century, first by Emperor Theodore and later by Sudanic dervishes. At the same time, he supplements his income by producing protective amulets for local folk.

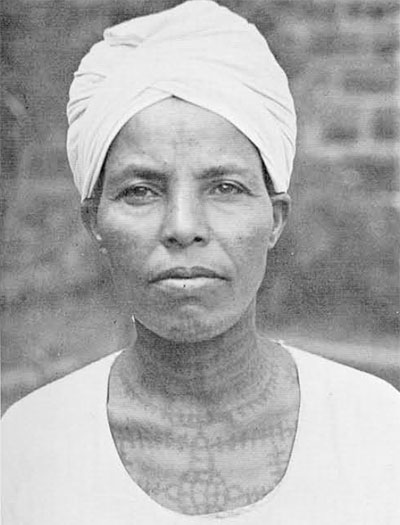

Amhara tattooing provides an interesting complement to church painting and talisman drawing. Whereas the last two share obvious religious connections in manufacture and use, tattooing is typically the product of a laywoman whose operations—prophylactic, therapeutic, and cosmetic—are unconcerned with the forces of good and evil, saints and demons, which so preoccupy churchmen. But of greater interest than the enumeration of goals to which painting, drawing, and tattooing has each been put, is the examination of how the Amhara artist attempts to best achieve these ends. It is to these techniques and conventions that we now turn.

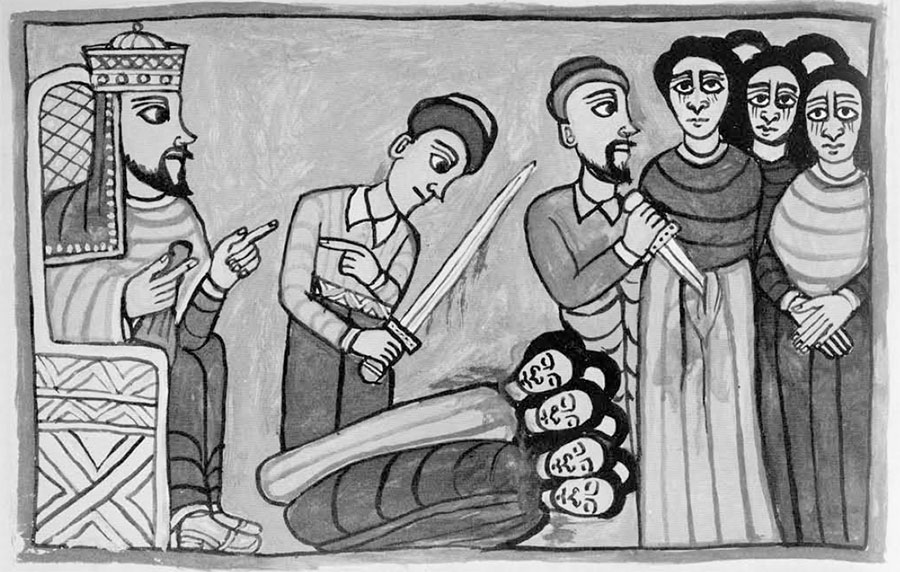

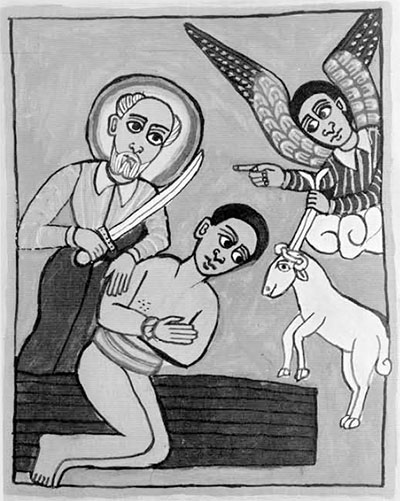

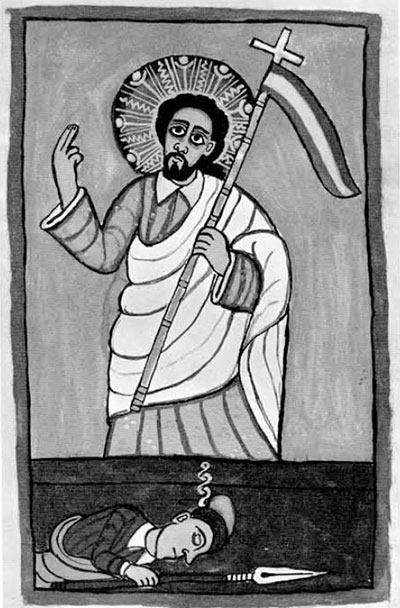

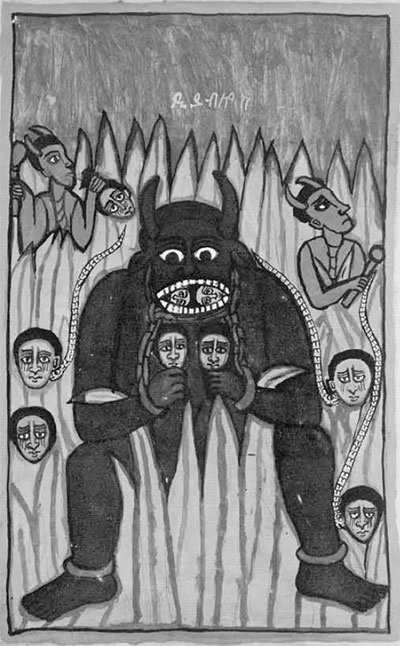

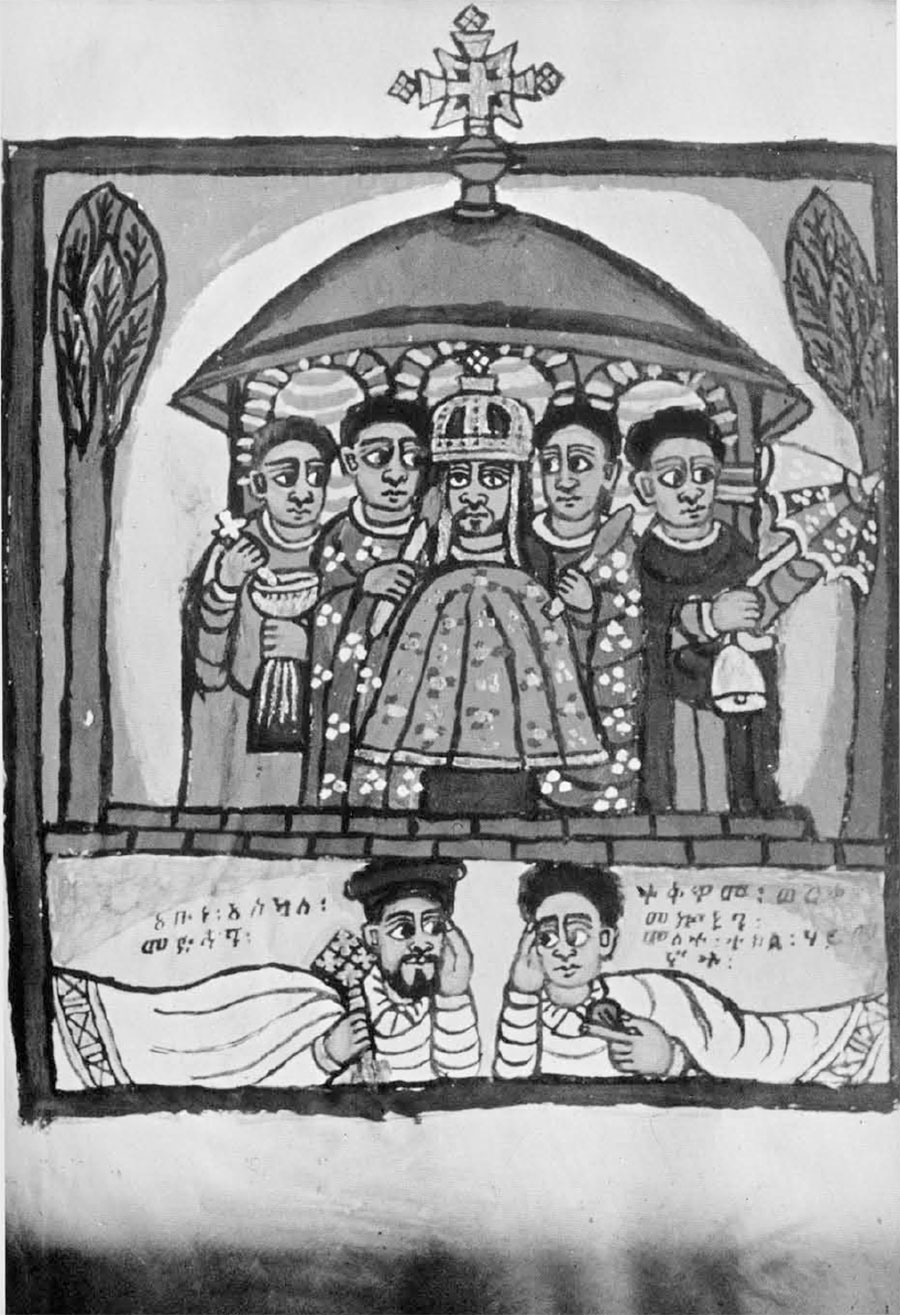

Ethiopian church painting is characterized by conventions of composition and content which reflect the pre-occupation of Amhara society with differences in social rank and spiritual purity. Neither concern is unexpected, of course, in a strongly feudal state, perpetually threatened by the military incursions of infidel enemies, and containing seditious religious minorities within its boundaries. The person or rank, for example, is characteristically pictured in the traditional raiment of Ethiopian royalty. Compare, for example, Adam and Eve, Herod, and Emperor Fasilidas; Herod’s crown, however, is mounted with a simple orb, whereas those of Adam and Eve bear the crucifix, an honor extended to all Old Testament figures whose stature and divine grace are equal to those of the first mortals. Whereas the Western artist manipulates image size and visual detail to indicate spatial perspective, the Ethiopian church painter often employs them as criteria of social rank, as in the painting in which the satanic commander looms over subordinates and victims alike. Although the physical height of real satans and men is not believed to bear any necessary relationship to rank or power, linguistic convention also equates “big man” (tillik sew) with man of power and “little man” (tinnish sew) with the commoner.

Miscellaneous ethnographic details are similarly employed: Although the Holy Family in the painting shown here is not treated in the regal fashion customarily afforded Virgin and Child, it possesses nonetheless a mule in contrast to the less prestigious ass, its members are garbed in decent robes rather than the humble toga, and they are accompanied by a maid servant.

Differences in spiritual purity are greatly simplified in the paintings by opposing the “good” with their oppressors. The former include Christians and their biblical progenitors and are generally depicted full-face, opposing their antagonists in attitudes of defiance and martyrdom. Evil fellows are usually portrayed in profile. The painting representing the commander satan is an interesting exception in this regard; submitting to the demands of dramatic emphasis and Christian charity, the artist has painted the hell-bound sinners and the commander satan en face. This violation of convention is particularly effective when seen upon a church wall: One’s eyes skim over the numerous panels, a giant comic strip from which angels, saints, and Christians stare, impassive, moon-faced and pale. From which evildoers of ancient standing, Muslim, Jew, and pagan, cast glances furtively aside. And, then, just as garish colors and stereotyped postures are about to melt one panel into another, just about to insinuate a deadening languor, the eye catches on this black face with its magnificent white teeth, shoving its brazen maw into one’s face, while lesser fellows turn away.

When first asked the provenience of the distinctive caps and tunics worn by Herod’s men, seen slaughtering the innocents, the artist identified them as the national costume of the Israelites. A week or so later, however, I was shown his illustration of the Flight from Egypt, in which a band of bare-headed and berobed Jews, led by a monarch bearing a crucifix upon his crown, is pursued by Pharaonic soldiers wearing these caps and tunics. The clothes appear, then, emblematic of all evil mortals, or at least commoner poltroons. There is, in fact, remarkedly little in the church paintings of an exotic character. A final structural convention, again in the depiction of the slaughter of the innocents, is the opposition of good and evil as right to left.

The artist of these pages has not always shown a scrupulous regard for the conventions of traditional painting; one, the coloring of good men paler than evil ones, he has neglected altogether. This represents less a conscious attempt to innovate, than an occasionally lackadaisical regard for his work, a lack of professionalism, the results fo which some future painter will perhaps attempt to rectify. His conscious innovation in the paintings is trivial, the substitution of European-style shoes for the sandals which appear in earlier works. Greater freedom was taken when the artist painted incidental areas, such as the wooden frame to the sacristy entrance, considered too narrow to serve as a full panel. Whereas such areas have been customarily decorated with angel heads and parti-colored geometric designs, this artist has painted several of these areas with the alternating profiles of Land Rovers, bicycles, and boys at play.

Compositions similar to church murals are frequently painted upon the goatskin parchment pages of religious texts, where they serve as illustrations of the content and application of textual material, and as guides for future church paintings. A large proportion of these pictures depict ecclesiastical scholars (the most frequent owners and transcribers of such books) at devotion, instruction, and engaged in exorcising the evil spirits responsible for the largest share of man’s misfortunes.

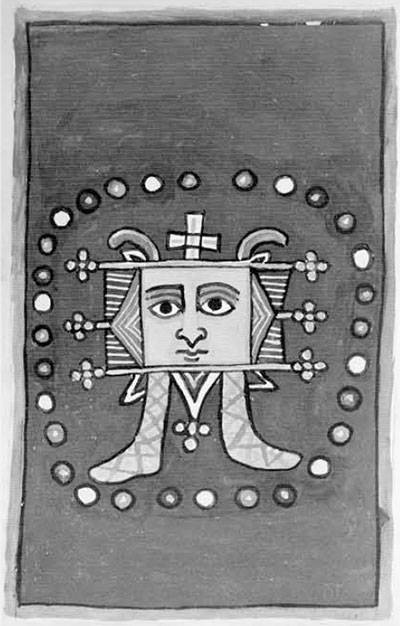

Talismanic designs are generally never seen by their owners, for whom such drawings are hopelessly obscure and whoa re more intent upon preserving talismanic efficacy from the doleful effects of sun and water than in satisfying idle curiosity. Also, since talismans must be circumscribed by a written magical text into which the owner’s name has been inserted, they are non-transferable and must be produced anew for each client. There are a substantial number of talismanic designs, and selection for specific clients is dependent upon both the fabricator’s particular repertoire and his reading of the divinatory tables which determine the combination of drawing, charm, and herbals best suited to the purchaser’s needs and astrological profile.

The church painter enjoys the good graces of the ecclesiastical hierarchy for his services; his name is not forgotten at the annual division of tithe crops, nor is he unwelcome at the frequent mortuary and baptismal feasts provided by parishioners. The amulet maker, or at least amulet making, is officially proscribed by the Church, which stresses reliance upon orthodox prayer and ritual in opposition to magical usages. The greatest contrasts between church painting and talisman drawing lie in details of production. The church painter, applying his knowledge of church lore and artistic convention, creates sacred scenes from profane materials, working with commercial poster colors upon muslin woven by Muslims or Ethiopian Jews (Falasha). The talisman drawer, in contrast, produces simple duplicates; for any submission to private inclination can only be destructive to the talisman’s effectiveness. That is not to say, however, that the amulet maker is without opportunities for manipulation, opportunities to enhance the final effect by selecting one option while rejecting another. Whereas the church painter picks among compositional conventions and potential subject matter in order to produce a didactic effect, the amulet maker must turn to a choice of physical materials so as to better repulse the demons which threaten his clients. The occult drawing may be set upon paper, bark, or skin; but, if skin, the amulet maker must decide if it is to be goat, antelope, or hippopotamus; and, if goat, whether it is to be from a nanny now suckling a kid of its own color or perhaps from an all-black he-goat. Of the various pigments, one or more must be chosen as appropriate; then the talisman drawer must decide whether to alloy it with the sap of this leaf or the juice of that plant; whether to draw it using the reed of this plant or a feather of that bird. The amulet maker, as well, may observe various prohibitions prior to drawing the talisman, such as refraining from sexual congress, social intercourse, or the drinking of beer and mead. Then, he must decide upon the period of observance, usually one, three, or seven days.

Often, when an amulet maker learns a new talisman and accompanying magical text, the donor will include various of these details, which have proven efficacious in combination. Otherwise, it is necessary to search divinatory tables for assistance. In either event, whatever “meaning” may be buried in the various combinations of detail (for example, red ink with juice of lemon upon monkey skin) beyond their effectiveness in repelling demons, the talisman maker is content to abandon as a mystery and an irrelevance.

Differences in skill and mastery of technique mark one man’s church painting as definitive and another’s as temporary, while differences in occult knowledge and powers characterize this talisman drawer as an expert and that as a mere “peddler.” There is little, however, to recommend one tattooer above her colleagues, and potential customers often select the tattooer most conveniently near. Working with a double needle, she produces a variety of geometric patterns from a repertoire of more or less standardized designs. The crudeness of the traditional technique renders differences of execution minimal, and tattooers generally differ amongst one another only in their knowledge of medicaments to be mixed with pigments prior to inscription. But, even here, differences in the efficacy of herbal formulae are not considered particularly relevant by clients.

Many designs are specific for body area and ailment; the zigzag, for example, customarily appears as multiple necklaces and is directed against goiter. Other patterns may be inscribed on several areas; circles and crucifixes appear on forehead and temples to prevent recurring headaches, on the forearm for muscle paralysis, and at joints for rheumatism. The effectiveness of the designs is by means of an unknown modus vivendi, and innovation is discouraged on this account. Cosmetic and medical motives are frequently difficult to distinguish from one another: Prophylactic and therapeutic tattoos on face and throat are often regarded as fortuitously enhancing the bearer’s beauty. Similarly, essentially decorative tattooing is sometimes given a secondary, prophylactic, rationale; the “beaded ankle” motif, for example, is believed to attract the witch’s evil eye away from the vulnerable mouth area.