The ancient Maya created one of the world’s most brilliant and successful civilizations. But 500 years ago, after the Spaniards “discovered” the Maya, many could not believe that Native Americans had developed cities, writing, art, and other hallmarks of civilization. Consequently, 16th century Europeans readily accepted the myth that the Maya and other indigenous civilizations were transplanted to the Americas by “lost” Old World migrations before 1492. Of course archaeology has found no evidence to suggest that Old World intrusions brought civilization to the Maya or to any other Pre-Columbian society. In fact, the evidence clearly shows that civilization evolved in the Americas due to the efforts of the descendants of the first people who came to the New World during the last Ice Age, some 12,000 to 20,000 years ago.

Photo by Kenneth Garrett.

Maya civilization was part of this independent evolutionary process. Located in eastern Mesoamerica, the ancient Maya flourished in a diverse homeland in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador until the Spanish Conquest. The brutal subjugation of the Maya people by the Spanish extinguished a series of independent Maya states with roots as far back as 1000 BCE. Over the following 2,500 years scores of Maya polities rose and fell, some larger and more powerful than others. Most of these kingdoms existed for hundreds of years; a few endured for a thousand years or more.

To understand and follow this long development, Maya civilization is divided into three periods: the Preclassic, the Classic, and the Postclassic. The Preclassic includes the origins and apogee of the first Maya kingdoms from about 1000 BCE to 250 CE. The Early Preclassic (ca. 2000–1000 BCE) pre-dates the rise of the first kingdoms, so the span that began by ca. 1000 BCE corresponds to the Middle and Late Preclassic eras. The Classic period (ca. 250–900 CE) defines the highest point of Maya civilization in architecture, art, writing, and population size. The Classic period has Early, Late, and Terminal subdivisions, the latter overlapping with the Postclassic, and corresponds to the collapse of most Classic kingdoms and the beginning of the transformations that define the Postclassic period. The Postclassic saw a revival of Maya civilization beginning by ca. 900 CE and was cut short by the Spanish Conquest (1524–1697 CE). Over this span, uncounted generations of Maya people lived in villages, towns, and cities from the southern coastal plain and mountainous highlands of Chiapas and Guatemala, to the tropical lowlands of northern Guatemala, Belize, and Yucatan. The Maya created a sophisticated agricultural system, supplemented by forest, river, and seashore resources, to support a population that reached into the tens of millions. Archaeology has revealed this agricultural infrastructure, well adapted to varied highland and lowland environments. Excavated canals show that irrigation was employed in the highland Valley of Guatemala by the Middle Preclassic and expanded during the Late Preclassic. The lowlands hold extensive remnants of raised fields and drainage canals that made swampy land productive, and expanses of terraces that did the same for hilly terrain. Research has identified the agricultural bounty from crops like maize, beans, squashes, manioc, chili peppers, and cacao, along with domesticated turkeys, and cotton for skillfully woven clothing and textiles.

Photo by Kenneth Garrett.

Photo by Robert Sharer.

Photo by Robert Sharer.

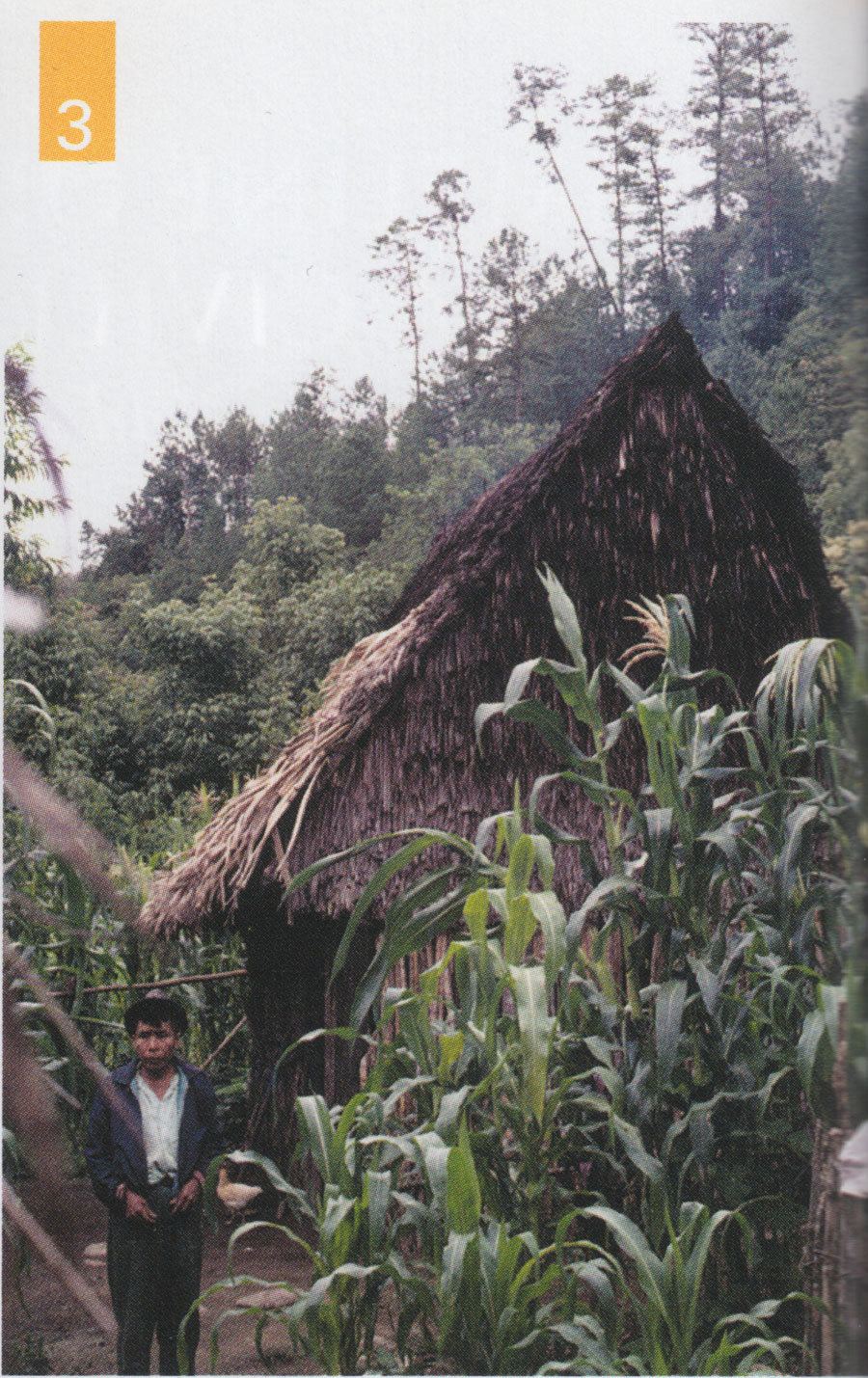

Ancient Maya society was founded on ties of kinship, class, and community. Every Maya polity was composed of an array of communities, large and small. The largest cities served as the capitals of independent kingdoms, containing the most elaborate temples, palaces, markets, causeways, reservoirs, and plazas. Lowland cities were mostly constructed of masonry; highland cities favored adobe and timber. In all Maya cities, hundreds to thousands of houses of the common people were constructed of adobe or pole and thatch.

In peacetime, these capitals and their people prospered from trade networks that connected them with other kingdoms. Many polities were also linked by alliances, activated during times of war. Yet these alliances never spurred development of a Maya empire, for the winners seldom absorbed defeated capitals and their inhabitants. Maya warfare was all about humbling foes and their gods to gain prestige and tribute. Capturing enemies was far more important than killing them. Families of the winners often adopted captives, although nobles and kings were sometimes sacrificed in ceremonies celebrating victories.

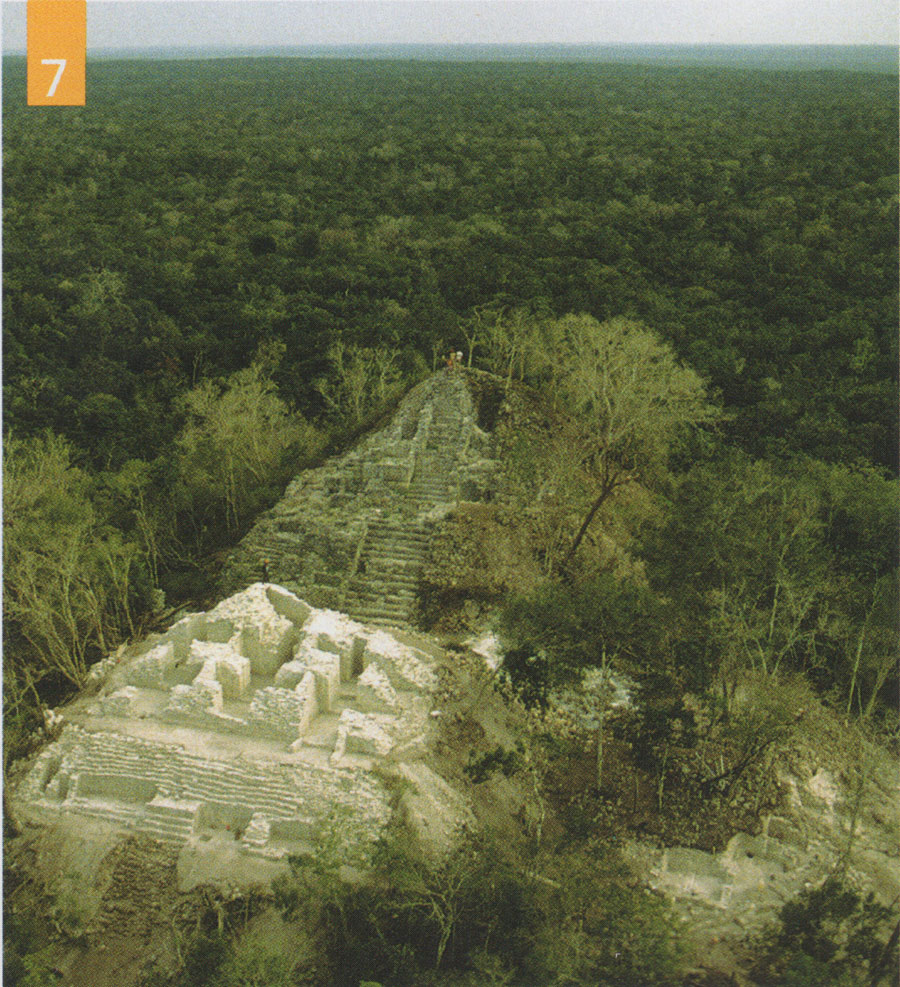

Archaeology provides evidence for Maya kings during the Late Preclassic era (by 400 BCE) (see page 28). With origins in the Middle Preclassic, the site of Kaminaljuyu—now mostly beneath Guatemala City—was the largest highland capital during the Late Preclassic. It produced many beautifully carved monuments, some with hieroglyphic texts. The largest known lowland Preclassic capital was El Mirador, located in northern Guatemala. El Mirador had an extensive network of causeways and contained several of the largest temples ever built by the Maya. It rose to power by 500 BCE and fell by 250 CE.

Photo by Robert Sharer.

Photo by Penn Museum.

Photo by Robert Sharer.

Photo by Kenneth Garrett.

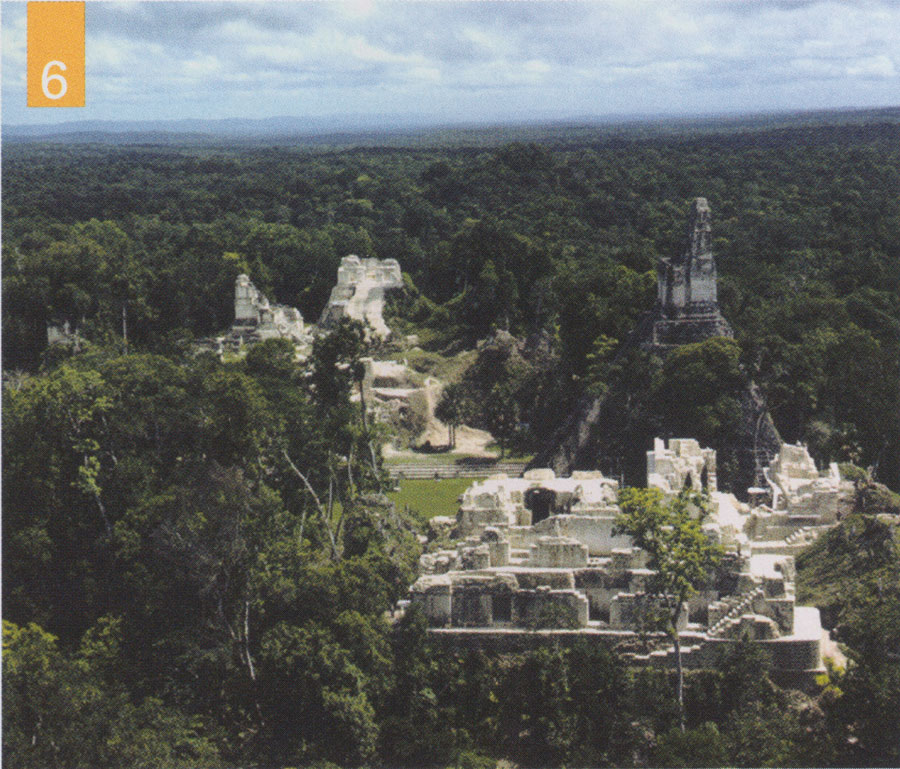

Our knowledge of Classic lowland Maya kingdoms has been vastly increased by deciphered royal texts that allow us to combine historical and archaeological information. Classic Maya kings were members of royal houses and dynasties of successive ancestral rulers. One of the greatest Classic period kingdoms was Tikal, which appears to have founded client kingdoms throughout the Early Classic lowlands. Tikal’s power was eclipsed after its defeat in 562 CE by an alliance led by the Kaan or Kan (Snake) kingdom. For over a century thereafter the Kaan alliance, led by the Calakmul king Yuknoom Ch’een II (636–686 CE), ruled supreme in the lowlands. But in 695 CE Tikal’s king Jasaw Chan K’awiil (682– 734 CE) defeated Calakmul and regained its former power before beginning a long decline after ca. 800 CE.

During the Terminal Classic period, overpopulation, reduced food production from depleted environments, warfare, and periodic droughts brought famine, disease, violence, and the abandonment of lowland cities by people seeking a better life elsewhere. These changes undermined the authority of traditional Maya kings and led to the collapse of most Classic kingdoms. Yet some kingdoms hung on and even prospered in this changing environment. Chichen Itza in Yucatan was the paragon of this development, and for about two centuries this city headed one of the largest and most prosperous states in Mesoamerica. It did so by advancing the authority of an elite council over the king, since royalty was discredited by the failures of most Maya polities. Yet Chichen Itza also ultimately failed, taking with it the last vestiges of the Classic era.

The Postclassic period was ushered in by a series of new states with transformed economic, political, and religious institutions. The new economy was based on utilitarian commodities such as salt, cotton, and obsidian rather than traditional prestige goods. The new political order was based on rule by councils instead of kings. The new religious order emphasized household ritual and pan-Mesoamerican deities that replaced monumental temples, mass spectacles, and the patron gods of Maya kings. Postclassic states prospered in the highlands and along the lowland coasts, controlling new seacoast trade. One of the most successful states was Mayapan, a less ostentatious northern capital that replaced Chichen Itza. Mayapan’s success was built on the heritage of Chichen Itza and by promoting an economy based on utilitarian commodities. This spurred the growth of mercantile elites and the middle class that managed the new economy. Mayapan fell a century before the arrival of the Spaniards, who began conquering a mosaic of Postclassic polities in 1524 CE. After more than a century of bitter conflict, the Spanish defeated the last independent Maya states in 1697 CE.

Photo by Robert Sharer

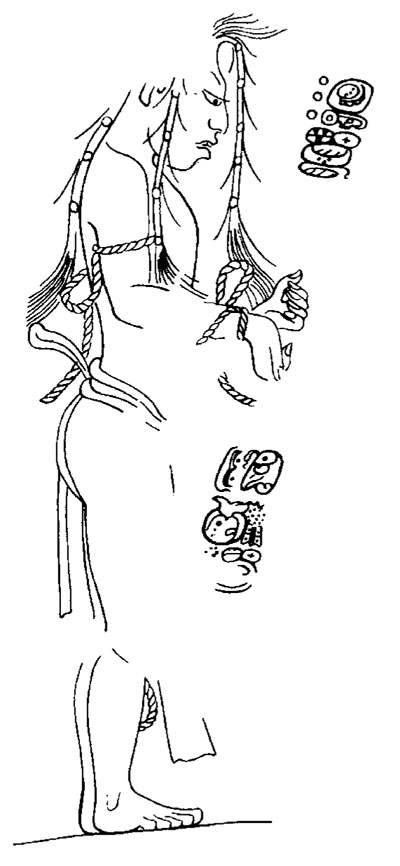

Although Maya kings and kingdoms have vanished, archaeologists and epigraphers have revealed much about their civilization. During their heyday, Maya rulers advertised their achievements with carved portraits on monuments and ordered the construction of splendid palaces and temples. Carved texts provide evidence for the reconstruction of the Maya political system as it developed during the Classic period. The decipherment of these texts has revealed the events and histories of Classic Maya kingdoms, along with their creation myths and religious practices.

We know far more about the elites of ancient Maya society than the more numerous common people. Archaeological research has favored polity capitals, along with the elaborate artifacts produced for the elite—carved jades, painted pottery, mirrors, and scepters. Classic Maya inscriptions are even more exclusive to the upper echelons of society. Recently discovered murals at Calakmul are unique in depicting merchants and other non-elite individuals with glyphs labeling their activities (e.g. “salt person”). Otherwise Maya texts and portrayals are all about kings and elites, not other members of Maya society. Fortunately today far more archaeology is devoted to non-elites. A more balanced view of Maya civilization comes from excavations of the settlements of the common people and smaller administrative centers without the trappings of royal power.

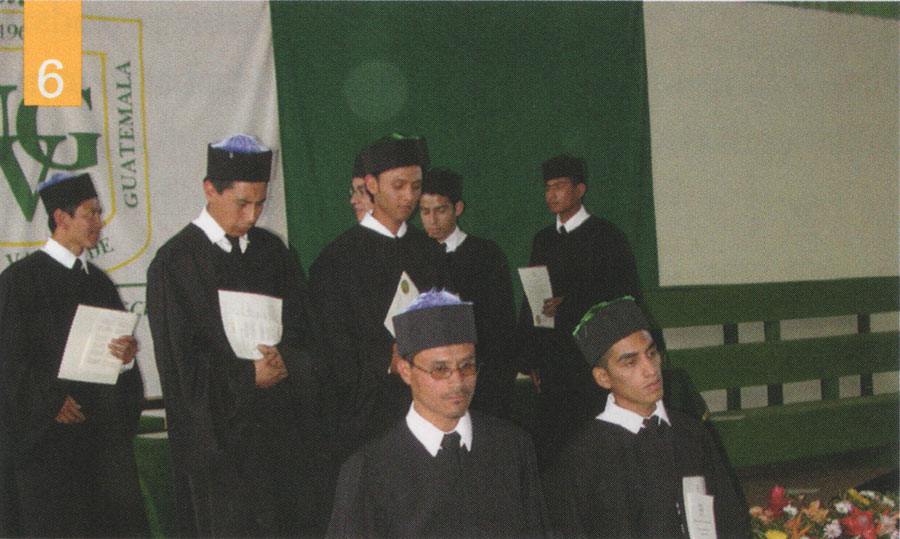

Interest in the “collapse” of Maya civilization, or descriptions of disease and destruction wrought by the Spanish Conquest, has led some people to believe that the Maya have disappeared. But the Maya did not vanish with the downfall of their Preclassic kingdoms, or from the more profound decline at the end of the Classic period. The Spanish Conquest ended Maya civilization, but the Maya people survived this trauma and 500 years of subsequent oppression. Today, several million Maya people continue to live in their ancient homeland and have retained their culture, their Mayan languages, and many of their traditions.

Photo by Marilyn Masson

Photo by Jane Hickman.

Photo by Kenneth Garrett, courtesy of the Proyecto Arqueológico Calakmul, Ramón Carrasco, Director.

Farriss, Nancy M. Maya Society under Colonial Rule: The Collective Enterprise of Survival. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Jones, Grant D. The Conquest of the Last Maya Kingdom. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. Revised edition. London: Thames and Hudson, 2008.

Sharer, Robert J., and Loa P. Traxler. The Ancient Maya. Sixth edition. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.

Photo by Robert Sharer

Photo by Robert Sharer

Photo by Kenneth Garrett.