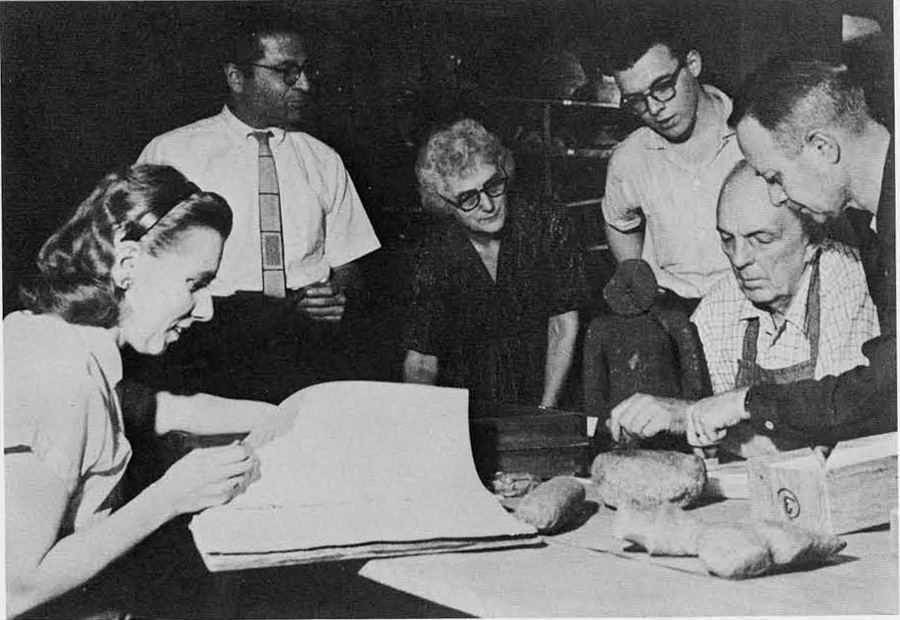

This term describes a dozen or two who work one night a week in the University Museum’s workshop and storage rooms, cleaning and repairing the many objects needing attention. Actually I don’t remember dusting a mummy, but we have done almost everything else–repairing Peruvian pottery, scouring and polishing metal weapons from Africa, and washing, sorting, and cataloguing hundreds of American Indian stone artifacts, among other activities.

When we are asked why we spend one night a week slaving at often menial tasks for no other remuneration than our own satisfaction and the coffee and doughnuts furnished by a grateful (I hope) Museum, we come up with various reasons. I can only give my own–and even these I find difficult to explain to quizzical friends and to my more lenient but equally puzzled family.

When we are asked why we spend one night a week slaving at often menial tasks for no other remuneration than our own satisfaction and the coffee and doughnuts furnished by a grateful (I hope) Museum, we come up with various reasons. I can only give my own–and even these I find difficult to explain to quizzical friends and to my more lenient but equally puzzled family.

My first experience with archaeology and museums came close to being my last. As a boy in school on a farm in Virginia I found about fifty stone arrowheads, and was convinced I had made a great discovery. On a trip to New York I took my treasures to present to the American Museum of Natural History, anticipating their delight and gratitude. I was prepared to be hailed as a great discoverer and to be interviewed by The New York Times. Alas, a polite but obviously bored assistant curator thanked me. Then he pulled out drawer after drawer full of perfect arrowheads. He would, if I insisted, accept my offering; but as space was limited, wouldn’t I please take them away?

That experience nipped my budding enthusiasm for archaeology. Years later I read E.G. Squire‘s Exploration and Excavation in Peru, and my interest in archaeology put fort new shoots. After reading all I could find on the Peruvians I started on the Maya, the Aztec, and so forth. Each presented challenging puzzles–the origin of each, the unconfirmed reason for the Maya moving from one part of Yucatan to another, the extraordinary folklore of the Aztec, whose belief in the coming of a White God facilitated their conquest by Cortez. And then there are the unreadable Maya glyphs. Although the ones recording dates, mathematics, and astronomy have been deciphered, we cannot decipher the rest with any certainty.

Thus step by step I was brought to our own archaeology and its tantalizing enigmas. When and from where did man first come to the Americas? This is a fast-moving problem, not a static blank wall. It wasn’t many years ago that no recognized authority would place man’s advent at more than about four or five thousand years ago. Now many authorities will admit that even thirty-five thousand years is a possibility. Constantly new discoveries are being made, and armed with the magic yardstick of Dr. W. F. Libby‘s Carbon-14, our experts are pushing back the horizons of our knowledge. Perhaps tomorrow we will read of the gain of another thousand years.

Where did this man first come from and how? These questions are two more will-o’-the-wisps. I have neither the knowledge nor the space to explore all the theories, but they are many and varied, firing the imagination.

Once you get started exploring the past you are bewildered by the many challenges. What of the highly technical “lost wax” method of gold casting? Yet it was practiced by natives so little versed in physics that, as far as we know, they had no knowledge of the simple wheel. How did the early Peruvians learn weaving, in many respects superior to that done today? How, with no hard metal available, did the Peruvians and the Maya manage to produce such extraordinary masonry? The curved, sloping wall at Machu Picchu is an example. I have promised myself to take a weekend off, go down to Yucatan and find a Maya Rosetta stone. I can’t imagine why this hasn’t been done by now.

Once you get started exploring the past you are bewildered by the many challenges. What of the highly technical “lost wax” method of gold casting? Yet it was practiced by natives so little versed in physics that, as far as we know, they had no knowledge of the simple wheel. How did the early Peruvians learn weaving, in many respects superior to that done today? How, with no hard metal available, did the Peruvians and the Maya manage to produce such extraordinary masonry? The curved, sloping wall at Machu Picchu is an example. I have promised myself to take a weekend off, go down to Yucatan and find a Maya Rosetta stone. I can’t imagine why this hasn’t been done by now.

Surely these problems will be met and solved just as equally difficult ones have been solved by the determination and selfless labor of dedicated men. For archaeology isn’t all artifacts, hieroglyphs, and dusty bones. Archaeology is rich beyond measure in the caliber of the men who, fighting ignorance and ridicule, have raised this science to its present high repute. Who can read, without being deeply stirred, of the persistency with which Schliemann pursued his dream that led to his triumph at Troy and Mycenae? Or read, without vicariously sharing, of the hardships of Stevens and Catherwood in the Honduras jungle when they opened to astonished eyes the spectacular ruins of the Maya? As you read, you struggle with Champollion as he finally masters the riddle of the Egyptian hieroglyphs, or with Ventris and Chadwick as they master Linear B.

These are but an infinitesimal few of the many stirring stories of the indomitable men who climbed the archaeological Peaks of Darien to show us a glimpse of new and far horizons.

Does that help explain the why of a Mummy Duster? Being one entitles you to feel yourself a private in the rear rank of the Army these generals led. When you think of it you stand nine feet high.

We Mummy Dusters are not expert, and often our inept efforts to be helpful must try the patience of the long-suffering members of the Museum Staff in charge of us. But they are kindly, dedicated folk cast in the mold of Job, which is indeed fortunate for us. They realize that we are doing our best to help preserve the handiwork of the men of the past. No one can certainly foretell the future, but without a knowledge of the past not even an intelligent forecast can be made.

My knowledge is slight and scattered; in fact I’m cited as one who knows many unrelated facts about many unimportant subjects. But archaeology is an important subject, and I challenge my accusers to match the fun I’ve had gathering my unrelated facts as a Mummy Duster working in the sub-sub basement of the University Museum.