For years women in tribal and rural Afghanistan have received minimal medical attention. The reasons extend far beyond the war against the Soviets in the 1980s or the Taliban rule in the 1990s. Men’s attitudes toward women’s health and women’s own concepts of health as interpreted by Islamic law and practice, combined with the fact that medical assistance occurs outside the walls of the very private household, contribute to a situation where women suffer and die patiently at home.

Health Conditions Among Afghan Women

Health maintenance as we perceive it in the United States is virtually nonexistent among Afghan women. Routine practices such as checkups and vaccinations are generally unavailable to poor rural women. Among both rural and urban women, exercise for strength, improved circulation, and cardiovascular functioning is unheard of.

Rural women, however, tend to be more active than their urban counterparts, as dictated by the daily chores associated with poverty: carrying water from wells or streams, gathering wood, brush, or grass for fuel (which can entail a long, strenuous hike in arid mountains just to gather enough to cook that night’s meal), cutting and gathering long grass for making brooms and baskets, and herding animals in certain areas, are just a few tasks usually associated with women. Those not burdened with these chores have the luxury of remaining immobile within their compound walls and subsisting on a diet of wheat bread, potatoes, and a few vegetables — such as assorted leafy greens, ochre, eggplant, peppers, turnips, and cauliflower — prepared over an open flame and cooked in large amounts of oil and salt. Meat and rice, considered the normal diet by outsiders, are actually luxuries, and the inclusion of dairy (yogurt) depends on whether the family owns cows or goats. Honey, nuts, and fruit can be found, but at a price.

Fasting from this diet during the month of Ramadan is one of the five principal duties of a faithful Muslim. The fast entails abstaining from both food and water, from sunrise to sunset. Exceptions are made in the case of travel or illness, in which case the person makes up the missed fast on another day. Children are not expected to fast, although fasting is imposed on girls at a younger age (7 or 8) than on boys (10 to 12), as are many duties and responsibilities. Children compete and boast among themselves of being able to keep the fast, and parents make no effort to discourage them. I have heard it said, by men, that pregnant and lactating women are exempt from fasting, but many of these women ignore the exemption and persist with the fast.

There is great pride associated with being able to emerge from the month with a flawless record. Occasionally, some miss a day. It might be that they did not wake up in time for the meal taken before daybreak, or, in the case of menstruating women, they are obliged to break the fast during their period when they are considered impure. But fierce competition is everywhere. A subject of conversation and laughter during Ramadan is whether a person is fasting or not. People compare how many days they have had to eat for one reason or another, and they create jocularity over offering tea to guests in order to test their ability to resist.

Medical caregivers working with Afghan refugees have often come to an impasse, faced with cultural attitudes that favor fasting over health. For instance, certain antibiotic treatments require drinking more fluid. Dehydration results from decreased fluid intake during Ramadan, particularly in the hot climate of the Peshawar Valley, in refugee camps where there is no electricity to run a fan. In times of fasting from both food and fluid, pregnant women do not get the necessary nutrition and lactating women risk depleting their milk supplies. If a doctor prescribes a medication to be taken three times a day at regular intervals, a fasting individual is likely to combine all three doses with the evening meal so as not to break the fast, interrupting the medication’s steady level in the blood. But in a society where adhering to the group’s cultural norms precedes the needs of the individual, it is hard to argue in favor of liquid intake to fight infection or to increase lactation when the group demands fasting.

Traditional Healing Practices

In many rural areas, medical facilities do not exist, or people choose other long-existing healing methods. Mullahs perform dam rituals, blowing the breath of healing while reciting prayers. They are also paid to write ta’wiz, healing prayers on paper, to be either consumed in water or sewn into leather or cloth and worn around the patient’s neck. There is a widespread tradition of herbal and homeopathic medicines, commonly sold in bazaars and referred to as “Greek.” And women make pilgrimages to saints’ shrines to pray for healing and fertility.

Childbirth usually occurs at home, with the aid of older female midwives. A complaint I often encountered as a nonmedical person was of postpartum bleeding. Somehow, a belief was initiated that a whiskey-soaked pack of cotton inserted into the vagina could stop this bleeding, and I was continually sought for whiskey for this purpose. The belief is widespread among Pashtuns, but whether it extends beyond this group is unclear.

Medical Facilities in Afghanistan

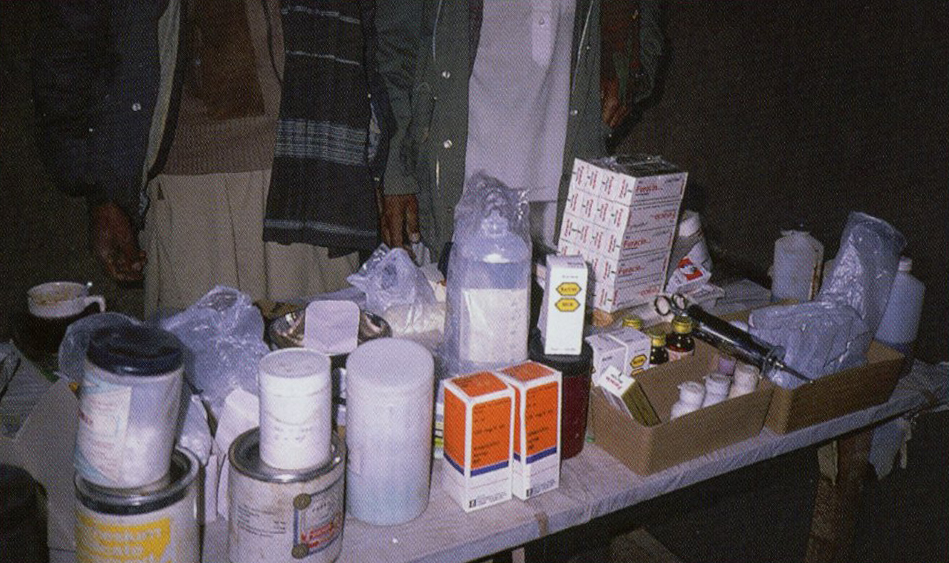

During the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s, many international organizations were established in Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province (NWFP), in and around the city of Peshawar, to help the millions of refugees settled there. Some of these organizations established satellite facilities in other border areas, such as Chitral, Quetta, and Thall, although they could not operate inside the independent tribal areas along the Afghan border where many refugees remained. The medical organizations were divided in their approach. Some of them set up hospitals and clinics to attend to refugees. The facilities were well frequented, often with long lines of people seeking attention from the foreign doctors. Other organizations also trained Afghan males inside Pakistan to become paramedics and return to Afghanistan to establish clinics in their communities. These organizations deemed this the most effective way to reach people remaining in Afghanistan because foreign personnel were not permitted to openly work there. The resulting clinics were never monitored or inspected during this time.

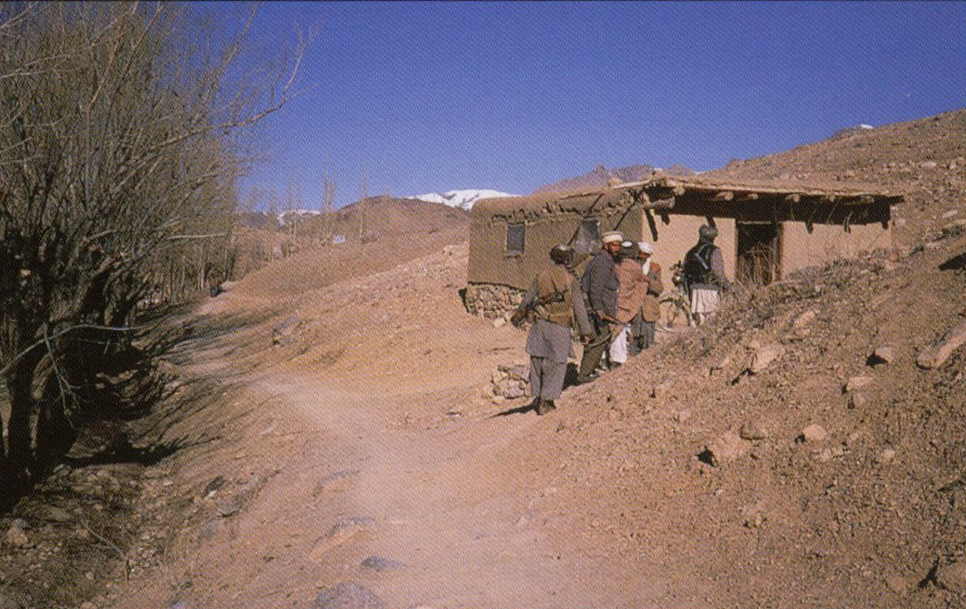

In 1989, after the Soviets had withdrawn, I visited the rural provinces of Logar and Wardak, on the eastern border of Afghanistan, to assess some of the clinics established by these foreign-trained paramedics. I visited many households whose members had remained in their villages throughout the war, or who were then returning from Kabul or Pakistan. I traveled with an Afghan paramedic (with Freedom Medicine) charged with restocking his organization’s clinics with medical supplies, inspecting the clinics while visiting, and comparing them with other clinics (Swedish or Saudi). My mission was focused more on the use of the clinics from the community’s perspective, and more specifically, on whether and how they were serving local women and children.

My first observation, confirmed by everyone I spoke with, was that women’s medical needs were grossly neglected and needed immediate attention. Clearly, the existing clinics were not meeting women’s needs to any degree but were there to cater to the mujaheddin, the warriors of the holy jihad. The women I spoke with complained that the clinics were either in the bazaar, the commercial area of town reserved for men and closely associated with the local mujaheddin center of political activity, or else situated so far away that they were inaccessible. In effect, most clinics were established in areas that were off limits to women, and the public nature of the activities inside them presented an obstacle to women. By comparison, girls’ schools in rural villages of neighboring Pakistan, where women’s segregation is equally an issue, are usually located away from the village center so that neither the female teachers nor the young women students need cross through the bazaar.

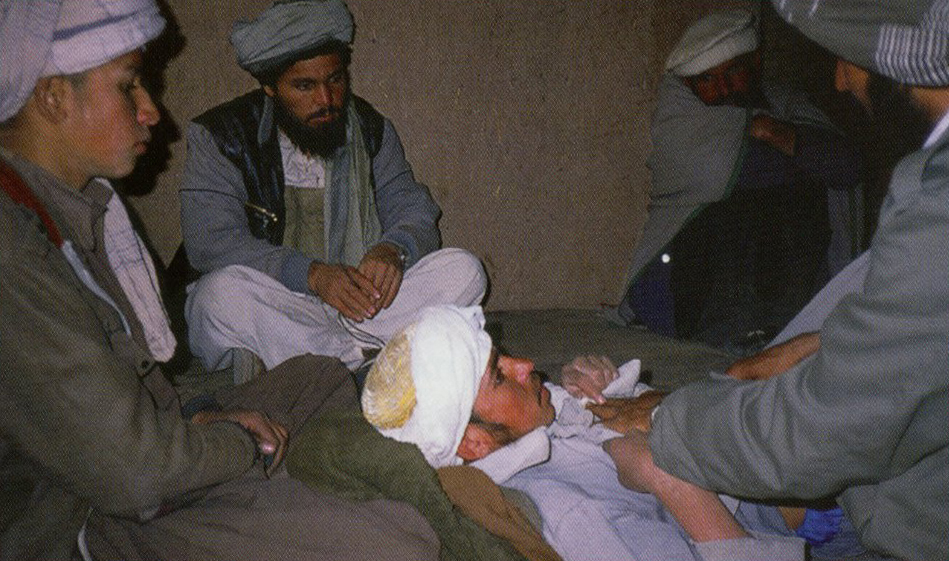

None of the clinics I visited, except one in Jaghuta, had a separate room for women. That clinic was run by the Saudis and was the only one I observed that was clean and located appropriately for women. The patient’s room in other clinics was usually filled with armed men seated along the walls of the room observing the doctor and patient. Once, I witnessed a paramedic passing around the earpiece of his stethoscope so observers could listen in turn to his patient’s heart and comment. This type of public observation of women is strictly forbidden in Islam. No woman, knowing the situation in a clinic, would subject herself to it, nor would any man allow the women in his family to be exposed in such a manner.

Cultural Obstacles

The women I spoke with claimed that even if they could go, rules of parda (veiling, modesty, seclusion from men) prevented them from fully exposing their symptoms. The few women I did observe at the clinics were elderly and presented age-related symptoms such as arthritis. Meanwhile, the houses I visited abounded with women suffering symptoms of severe whole-body, gas-induced skin infections, postpartum bleeding, bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, and respiratory infections. Many of these women were young and badly needed attention.

The hesitation women have to present their symptoms to medical personnel is in part cultural. In Afghan culture, most women, particularly those who are rural and nonliterate, do not take decisions upon themselves. They are either told by the legitimate man (father, husband, brother, father-in-law, or brother-in-law) which course of action to take or must obtain that man’s permission. Women must be accompanied on medical visits by a legitimate protective male figure. The Taliban did not invent this law, although they brought it to the fore, nor will it cease to be applied as a result of ending Taliban rule. It is a combination of Islamic law and local practice.

I came across many homes in which there were no men to sanction any action, such as consulting a male health specialist or purchasing a medication from the bazaar. The men had either been killed or had disappeared in war. Paramedics en route to and from clinics were often hailed by women unable to leave their compounds. I came across households of women living alone who offered free housing to other destitute families just to have someone to run medical and other errands.

A widow’s plight in Afghanistan is a harsh one. Common greetings and parting comments among women are “may you not become a widow’ and “may you not become without sons.’ In good times, a widow’s in-laws will keep her in the family, marrying her to one of their sons to legitimize keeping her and her children under their protection. But in times of famine, war, and poverty, such as the last two decades have brought on Afghanistan, many widows are turned out to fend for themselves in a society that otherwise condemns them to helplessness by a lack of tolerance for women without the protection of a male entourage. We have all seen pictures of these widows begging and combing the streets of Kabul for breadcrumbs. In Peshawar, a special refugee camp was established just for war widows and women whose husbands were wounded, in recognition of their special needs. This camp resembled a prison. There was little activity in its silent courtyard. Behind each closed door surrounding it sat a quiet, inactive woman, often with children, her life in the hands of God and destiny.

The idea that men are ultimately responsible for what women do outside the house raises two important concerns. Many men I interviewed were reluctant to expose their women to the young paramedics and health personnel. They did not fully trust these men who trained in Peshawar and returned as dubious authorities. They sought medications for their wives, sisters, and daughters, but did not want the women exposed to these young men. The reluctance of men to present the women to the male doctors is linked to cultural notions of women’s illness and well-being. So, even where men are available as escorts, women are denied medical assistance.

Illness Visits and Narratives

Afghan women deal with illness, depression, and misfortune through visits of condolence. When someone is ill or injured, related and unrelated women are obligated to inquire after them in a visit to the mother (or wife).

Equally important is bringing condolences at a death. These visits are crucial in maintaining family relations, and they follow strict rules of etiquette. It is the mother, or the wife, who is assumed to have suffered the most over the death and so deserves the recognition. These visits among women, practiced throughout the Muslim world, create a cultural context for tragedy and complaint that plays a major positive role in women’s lives.

In the case of illness, we get a glimpse of the crucial role a woman plays. The mother (or closest female relative) and other women of the victim’s family keep an open house, ready at all times to entertain visitors with food and a tear-filled account of how the person fell ill and how she, as the sufferer’s devoted mother, has stood by and been deeply affected. In her detailed account the mother provides a beautiful story of the suffering she has endured. Afghan mothers are expected to suffer over their sons in order to gain status and recognition. A wounded, ill, or dead son presents an ideal occasion to attain this recognition by way of a narrative of the event. It acts as a vehicle through which she can publicly display her actions for the benefit of the female community.

For the community of women, these visits, mandated by Islamic practice, provide an occasion for social mobility, narrative exchange, and maintaining family ties and exchanges, as well as scouting out young women as potential marriage partners for their sons. By contrast, a man’s inquiry of health can be performed over a handshake in passing and has none of the social implications it has for women. An Afghan woman perceives these visits as women’s work. It is her duty to know about other women’s lives. Detailed, questioning reporting is a perfected woman-to-woman communication style, and mental health is thus enhanced by the power of narrative.

The Male Perspective

Among many rural men, there is a longstanding attitude that women have no responsibility or work. They are fed, clothed, protected, and provided for, and therefore have no reason to suffer any ills. Not only have I heard this expressed often throughout my fieldwork among Pashtuns in the area, but I noticed traces of it in the way paramedics I observed responded to women when performing house calls. They were obviously overwhelmed by the large number of women complaining of symptoms beyond the scope of their experience.

One paramedic in particular made a point of having me accompany him on several house visits. Each time, he would laugh off symptoms with a hopeless shrug and smile. I sensed his hesitation at becoming too involved with women due to the overbearing demands and his incapacity to deal with them in depth.

The trained medic I was traveling with had a dying daughter at home. He perceived he could do nothing about her because he could not bring his wife back to Peshawar where he had no house for her. His wife was also ill and in no condition to travel. The family had abandoned hope for the daughter, still a toddler, and was just seeing to her basic needs until she died.

In another case, the wife of a very wealthy, highly educated man in Peshawar suffered from migraines. He had her treated medically, but she relied heavily on narrative healing, and daily received visitors of inquiry to whom she elaborated every symptom in lengthy detail. Her husband would make himself scarce each time, smiling to me as if to say, “Here we go again!” Although he seemed to make light of it, I wondered if he wasn’t actually admitting a certain helplessness toward her, like the paramedics toward the ocean of ills they knew was out there.

Women, on the other hand, endure the loss of daughters through marriage and of sons and husbands through death. They suffer destitution and abandonment by their own society when widowed or childless. Their losses are in fact too great for most outsiders to take on or do much more than empathize. Islam encourages hardship for women and presents contexts for them to express it openly. Pashtun culture further reinforces the merits of suffering and hardship for them, creating badges of honor woven from narratives of loss. Men’s helplessness and women’s aggrandizement in the face of suffering have a combined effect with the result that women lose out on medical attention.

A Better Future

One solution would be to establish all-women’s facilities in these tribal and rural areas. With that in mind, in 1989 I had located a number of women doctors, trained in Kabul and now sitting out the war in rural Wardak and Logar provinces. Although they were willing to practice again and provide clinical assistance for local village women, each of them, as coached by their husbands, insisted they would not leave the home but could only work from within their own walls. For the families of these medical personnel, the reputation of their women’s honor outweighed providing medical assistance to their local community.

The few, but poignant, examples I have given throughout this article should point to the importance Pashtun culture attributes to women’s isolation. Even when the stakes are life and death, cultural norms take precedence.

It might be argued that it is in opposition to men’s apparent indifference to their ills that women have cultivated the traditions of storytelling centered around illness and suffering, of shrine visitations and dependence on ta’wiz, and of alternative healing methods associated with religious beliefs. As long as women are perceived as being provided all they need, as long as the society cannot trust women’s ability to function outside the house without a male voice, their complaints will not be given credence.

Unless the new government gives tremendous support to trained female medical personnel willing to work in rural areas, women’s health care in those areas will remain unchanged while cities continue to receive attention. The needed support includes creation of some recognized status associated with the effort — at present only work in the urban areas offers this recognition.

With a centralized government, there is little social status attached to practicing medicine outside the major urban centers and the large medical facilities. In addition, relocation may present significant costs to a professional and his or her family.

Many Afghans in the United States are wondering how they can help get their former country back on its feet. This could be one area where the outsider really a former insider and already recognized as an authority — could plant the seeds of the prestige of practicing medicine in rural areas. These professionals, particularly women, may be recognized for having come from America with the prestige that this entails, as opposed to the local male paramedics trained minimally and ostensibly serving their political parties. I believe the two would have grounds for working together. Based on past results, we might witness a system that takes women’s needs seriously, offering them more options than storytelling, pilgrimages, and prayers.

Author’s Note

This article considers some of the major cultural factors affecting Afghan notions regarding health care. My dicussion draws upon 10 years of fieldwork — during which time I lived among rural Pashtun women refugees from Afghanistan in Pakistan — as well as a trip I took inside Afghanistan in 1989 to inspect the use of medical facilities by rural women. Being fluent in the language, I conducted research on women’s perceptions of life and emotion as expressed through their narratives.As a result, I can offer a few cultural considerations for establishing a health system in Afghanistan.