This page includes information that may not reflect the current views and values of the Penn Museum.

Visitors to our Lower Egyptian gallery are struck by the colossal scale of the architecture on display there. Towering columns, massive doorways and an enormous gateway entrance – all of which speak to the power of the Egyptian pharaoh. One is impressed when looking at this monumental architecture, but very detached. There’s a reason for that. These architectural elements come from a royal building — a ceremonial palace — constructed for the king to reside in when he took part in important religious festivals in the ancient city of Memphis. Most of the population would have no access to this palace. This palace — one of the few Egyptian palaces on display anywhere in the world — was excavated by Penn Museum archaeologist Clarence Fisher between 1915-1923.

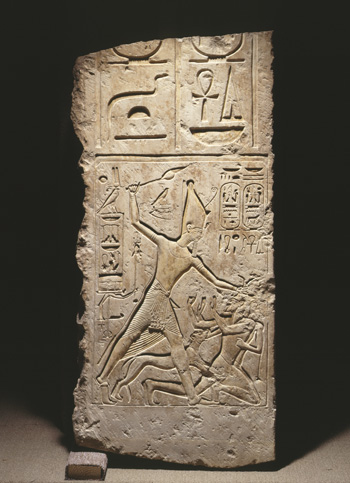

Images of the king interacting with the gods decorate the columns and the gateway. However, the only humans shown in the decoration (other than the king, who was, in reality, more or less a god himself) are the enemies of Egypt being bashed on the head by the pharaoh, Merneptah, in that timeless smiting pose seen in Egyptian art since the creation of the Narmer Palette around 3000 BC. So, while the king’s subjects built and decorated the palace complex, there are no traces of them anywhere.

Or are there?

Door Jamb, Memphis (Palace of Merenptah), Dynasty 19 (reign of Merenptah, 1213-1204 BCE), Limestone. Penn Museum Object E17527.

Careful observers will notice somewhat humble human touches — elements of graffiti — presumably left thousands of years ago. Graffiti is not a recent invention. People have been leaving their personal marks in places where they probably weren’t supposed to, since time immemorial. And just like some modern graffiti, ancient graffiti is actually kind of cool and very informative. There are Egyptologists who specialize in studying ancient graffiti and the information they can glean from them.

On two parts of the gateway jambs, if you look closely, you can see two examples of ancient graffiti. One is a tiny fish. The other is a seated woman with a child on her lap. They’re a little hard to find, but you can spot them in these locations:

The gateway of the palace of Merneptah. The fish is located in the blue area in the image on the left. The seated woman can be seen in the area of the white circle on the right

Who left these marks? When were they left? Why did they choose the imagery that they did?

Unfortunately, the answers to those questions are not so easy to come by.

Let’s start with the little fish.

The Nile River was home to a number of different species of fish. At some points in Egyptian history and in some locations in ancient Egypt, eating fish was taboo. At other times, this was not the case and excavations certainly turn up plenty of fish hooks and fish bones indicating a diet rich in fish.

The fish symbolized a number of different things for the ancient Egyptians — some good, some really bad… [If anyone’s really very curious about fish in ancient Egypt, I recommend taking a look at the book by Douglas Brewer and Renée F. Friedman, Fish and Fishing in Ancient Egypt (1989).] The Egyptians used images of the tilapia fish as a symbol of rebirth and regeneration. (You can see a nice faience bowl with a tilapia on it (E14359) and a rattle in the shape of a tilapia (E13005) in our Daily Life room.)

In some parts of Egypt, the Oxyrhynchus fish was highly regarded. (We have a nice Oxyrhynchus fish on display in the Secrets and Science exhibit. [54-33-6])

On the negative side, a fish was the creature blamed for eating Osiris’ phallus after his evil brother Seth dismembered him and cast his body parts into the Nile. This understandably could give a fish a bad reputation.

It’s hard to tell what species of fish is represented in our graffito. We find six distinct fishes depicted in hieroglyphs. For those of you who’d like the specifics, they are the Tilapia nilotica, Barbus bynni, Mugil cephalus, Mormyrus kannume, Petrocephalus bane and the Tetrodon fahaka.

Our fish doesn’t seem to have the long “snout” associated with the Oxyrhynchus fish (Mormyrus kannume). Nor does it have the shape of either the tilapia or the Tetrodon fahaka fish. Of the remaining three: Barbus bynni, Mugil cephalus, Petrocephalus bane, ours is dissimilar to all of them in that while its belly has some schematic scales scratched in, it is not shown with any pelvic or anal fins –features with which each of these fish are typically depicted.

In addition to the symbolic meaning of the fish for the ancient Egyptians, it should be noted that the fish was an early Christian symbol representing Jesus Christ. Christianity came to Egypt quite early and it is also conceivable that this fish was incised by an early Christian (although the fish shown here doesn’t look like the typical ichthys fish).

What about the seated woman? Who is she and what could her story be?

The woman holding the child on her lap probably represents the goddess Isis holding her child Horus. Marsh plants surround her, while another figure seems to be offering her a large lotus flower. Depictions of Isis holding her son Horus were a popular subject in ancient Egypt. This same motif appears on tiny amulets, in statuary, and on walls of temples. (We have a lovely bronze statue of Isis and Horus on display in our Amarna gallery. [E12548]) The marsh elements surrounding her throne/seat may reference to the myth in which Isis had to take her newborn baby and hide him from his uncle Seth. Seth had already killed Horus’ father Osiris and he would have been happy to make short work of the infant Horus, his competition for Osiris’ throne. Isis fled with her child and hid in the marshes of Lower Egypt. While there, a poisonous creature bit the child and Isis had to use her considerable magical powers to cure him.

Scenes showing women who have recently given birth are also similar to the figure in this graffito. These scenes typically show the mother seated in a birth arbor decorated with vines. She nurses her newborn baby while one or more women tend to her and offer her symbolic items like mirrors and flowers. If this graffito does not depict Isis, but rather a human mother, perhaps it was scratched there as a votive offering as a wish for a successful birth, or in thanks for one. Post-birth scenes such as this also call to mind the birth brick discovered by Joe Wegner at Abydos in 2001. That brick is similarly decorated with a scene of a woman holding a newborn baby.

Since we’ve pointed out that the fish can be a Christian symbol, it is interesting to consider that while the image on the gateway looks very much like a typical Isis and Horus scene, it has also been noted that imagery of Isis and the child Horus is a similar precursor to Christian imagery of Mary and the baby Jesus, (although to be fair, we don’t usually find her seated on a throne in a swamp…). It seems a link between this image and early Christianity is tenuous at best.

So, with our fish and our seated woman, we really are left with questions rather than answers. But, both images are an interesting, and perhaps little-noticed “human” addition to the gateway of the palace of Merneptah.