Surely them ost surprising and possibly the most significant result achieved from two seasons of digging at Tell es-Sa’idiyeh was the discovery that there had been a sophisticated and cosmopolitan culture at the site during the Late Bronze Age. One has learned to expect something more than provincial artifacts at ancient cities along the seacoast within easy reach of Bronze Age ships and on the major caravan routes of Palestine; but it is a surprise to find a truly cosmopolitan culture deep in the Jordan Valley, separated from the obvious trade routes by the barriers of a high mountain range and a river.

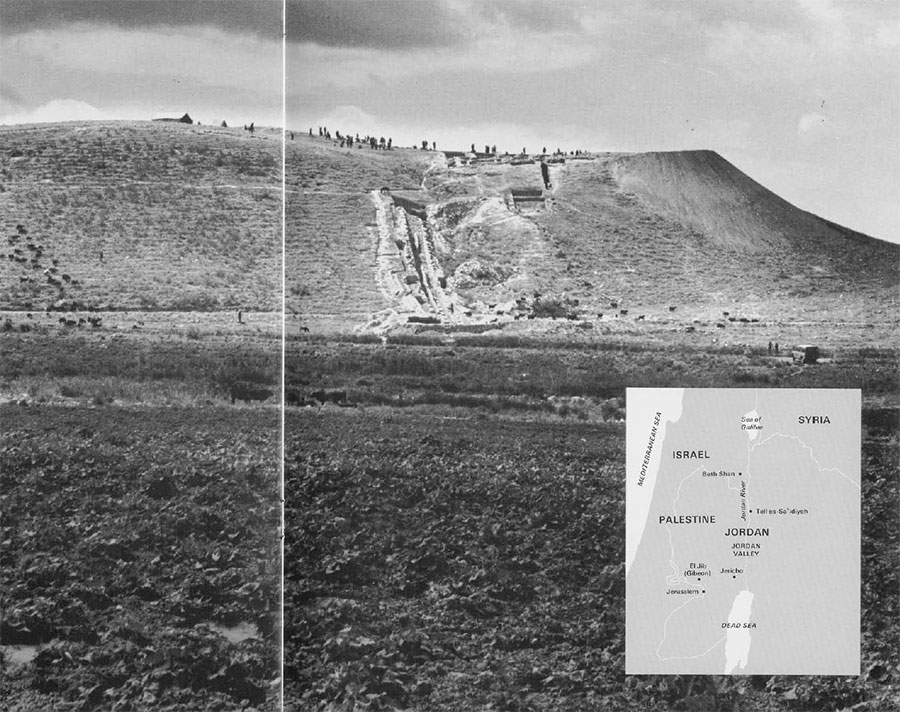

Today, Tell es-Sa’idiyeh is bypassed by the modern trunk road that traverses the length of the Jordan Valley. For most of last winter we were able to negotiate the two miles of muddy and rutted track that provides the sole communication with the outside world only by engaging the four-wheel drive of the expedition’s new Land Rover. After an uncomfortable and sometimes terrifying ride one climbed to the top of the mound to stand in a Bronze Age city that was a center of trade and commerce with such distant lands as Egypt, Cyprus, and Syria.

We shall probably never find the ancient roads that carried the traffic with the outside world, but the general lines of communication can already be traced from the imported goods found buried within the 13th century B.C. cemetery, that was first discovered during the excavations of 1964. The sixteen graves recovered during that season have now been supplemented by twenty-eight new ones recorded during the past winter. Although as yet we have not penetrated to the occupation level of the tell corresponding to the age of the cemetery, we have already found documentation for the diversified and rich culture belonging to this city that stood beside the Jordan when Joshua made his famous crossing into Canaan.

A measure of the extent of foreign influences upon the culture of the Late Bronze Age city is to be seen in the contents of Tomb 117, the very first tomb to be excavated in 1965. Of the twenty-nine objects recovered from this burial of the 13th century B.C. only one, a storage jar, was of local form and fabric. Unmistakable imports were three Mycenaean stirrup vases and a base-ring vase from Cyprus. A jar and seven platters have their closest parallels in ware found in Egypt. Along with four scaraboid beads was a bronze ring on which was mounted a scarab bearing what appears to be the cartouche of Amenhotep II. A delicately fashioned cup of translucent alabaster is of a type made in Egypt and frequently exported to the Syrian coast as far north as Ras Shamra. Also extraneous to the local Palestinian culture are a Mycenaean jug and a bowl with a beadlike spout made of pale blue faience. A bronze wine-drinking set, consisting of a bronze bowl and fragments of a strainer for removing dregs, evidences a high degree of skill in the working of metal.

The burial itself reflected a custom that is thus far duplicated only by that found in the warrior’s grave of the previous season. After the body had been wrapped in cloth it was covered with a thick coat of bitumen, placed on a bed of stones with the head to the west, and covered with several layers of sun-dried bricks. The impression of the cloth in which the body was wrapped has been well preserved in the bitumen. One can only conjecture as to whether this was the tomb of a foreigner buried with his own possessions or the grave of a native of the region affluent enough to purchase these imported luxuries.

One rich tomb barely escaped an archaeological calamity. Tomb 119 was discovered so late in the day that it was impossible to draw and remove the valuable objects before dark. Photographs were taken of the objects arranged around the head and feet of the skeleton and a guard was hired to watch the tomb until the work of sketching the objects and skeleton could be done on the following day.

When we arrived at the tell the next morning the distraught guard greeted us with the news that during the night someone had destroyed the tomb. He confessed that he had been frightened by the spirits of the dead, had moved some paces away, and had gone to sleep.

As we surveyed the damage it was soon clear that the marauder had carried off nothing but a small juglet; he had only broken and disarranged the pottery and a bronze cup, all of which could be repaired. Later that day a visitor arrived bearing proudly the parts of the one missing juglet which he had retrieved from a stream several hundred yards from the looted tomb.

The most important object within the tomb was a unique bronze cup with a graceful handle in the form of a gazelle’s head. The neck of the animal is riveted to the shoulder of the vessel and the two horns curve backwards from the head to join the rim of the cup. The handle to this cup, found along with a bronze bowl and a bronze mirror, is the finest example of bronzeworker’s art yet discovered at this site that has produced other outstanding examples of skill in bronze work. Fortunately the pieces of the cup are available for a full restoration.

With the evidence for the high level of sophistication of the Late Bronze Age city there was a reminder of an unhappier side of community life. Infant mortality was high. About half the total number of burials within the cemetery were those of infants or small children. In one large jar there were skeletal remains of three infants; and another burial consisted of a mother with a fully developed fetus and a child of a year buried upon her shoulder. The tomb deposit of a child burial consisted of only one accessory, a conch shell, which was probably the child’s toy.

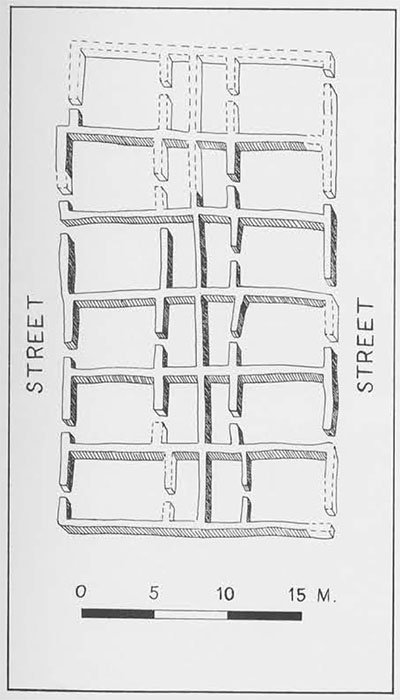

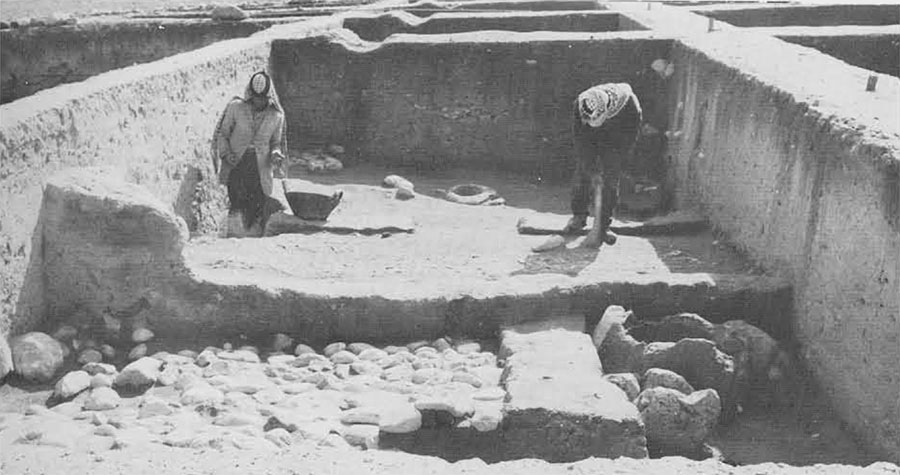

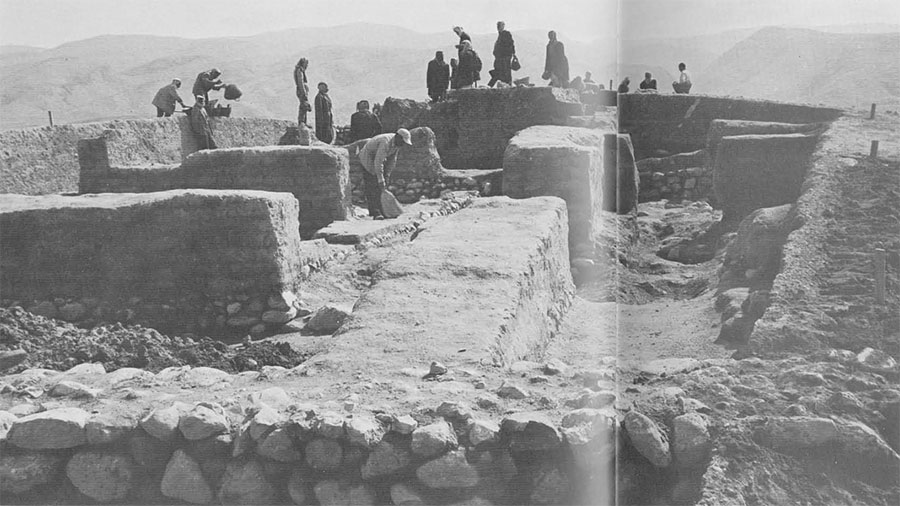

Another period of the city’s long history is the Iron Age settlement of about the 8th century B.C. Thus far we have recovered an entire block of houses laid out and constructed at one time. There are twelve row houses, identical in size and plan, six on each side of the block with a common wall separating one row from the other. Each house measures approximately 17 by 24 feet. A door from the street opens into a courtyard in which there were usually a mill for grinding grain and a closed oven for baking bread. Adjoining the unroofed area was a shelter for sleeping and for work such as weaving, a craft documented by the finding of scores of loom weights. At the back of each house was a closed room for the storage of foodstuff and other possessions. The narrow streets were kept clean by the rainwater that coursed down them from the roofs of houses.

The roofs, although destroyed by a terrific conflagration in the 8th century B.C., were easily identifiable in the debris lying on the floor. The walls had been spanned by wooden beams overlaid with reeds, probably cut from the luxuriant growth along the banks of the Jordan only a mile away. A coating of clay spread over the reeds served to keep out both the heat and the rain.

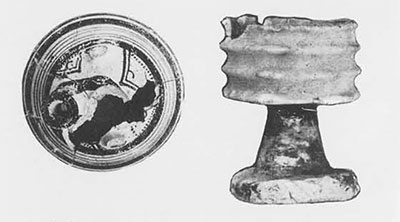

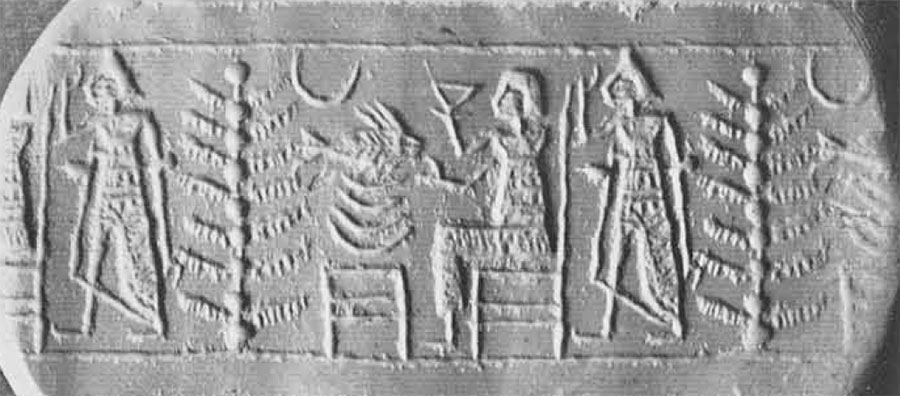

The daily life of those who lived in this housing development can be readily reconstructed by hundreds of objects found on the floors when the city was suddenly burned: cooking utensils, knives, jewelry, pottery vessels for storing food, agricultural tools, weapons, and other relics which have survived the decay of twenty-seven centuries. Religion and art are represented by the carving on a cylinder seal found on the floor of one of the 8th century houses. This cylindrical stone, 1 3/8″ long by 1/2″ in diameter, is engraved with a ritual scene in which there appear the elements of a sacred tree, an offering table with a fish upon it, a seated figure, and an attendant. The cylinder was pierced longitudinally so that it could be worn as a charm around the neck and used for identifying the owner by its impression left on the wet clay of a sealed document.

After the burning of the well planned city of the 8th century the mound was never again extensively built over. The residential area was eventually leveled off to serve as a threshing floor. More than seventy-seven circular pits were cut into the floor as storage bins for grain and chaff. Over some of them temporary shelters of reed and mud supported by wooden posts had been constructed to protect the threshers from the heat of the summer sun.

Toward the end of the 2nd century B.C. the acropolis of the mound was occupied by a massive Hellenistic structure that probably served as an administrative or government center for the entire area. The building measures 43 by 69 feet and consists of a large hall at the east end; from it a corridor flanked by three rooms on each side leads toward the west. The building had been completely burned; the charred beams and the broken pottery on the floors will provide adequate means for dating the destruction.

The earliest level of occupation yet reached contains floors and house walls of the Early Bronze period (beginning about 3000 B.C.). In a sounding made into the Early Bronze Age remains on the lower tell it was apparent that they had been violently disturbed by an earthquake. The tectonic disturbance had produced a fault that was apparent in the lines of the sedimentation of the virgin soil. This shock would have been sufficient to demolish the strongest brick walls. In fact, on the higher tell, a segment of a wall some ten feet long had been violently thrown from its base onto the floor, where it had remained until this year with its bricks firmly in place. These and other evidences for the destruction of cities by the earthquakes which seem to have been frequent in the Jordan Valley, would seem to corroborate the ancient biblical tradition contained in the dramatic story of the tumbling walls at Jericho.