The Department of Oriental Antiquities in the Louvre in Paris is the fortunate possessor of the remains of a Sumerian document inscribed with more than thirty-five hundred years ago with what are by all odds the most minute cuneiform characters yet known. In the course of the past hundred years or so tens of thousands of cuneiform documents have been excavated, and some of these are inscribed with rather small and crowded writing. But, as far as I know, none has been found inscribed with such microscopic a script as that on the piece in the Louvre. The characters are so minute, that we wonder how the ancient scribe succeeded in writing them, and how, once written, he could read them without magnifying glass or microscope.

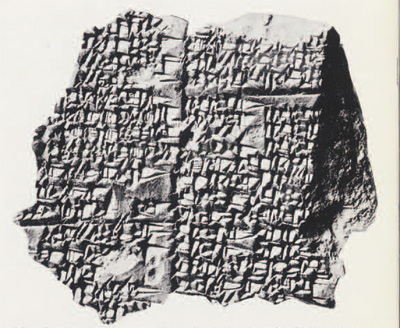

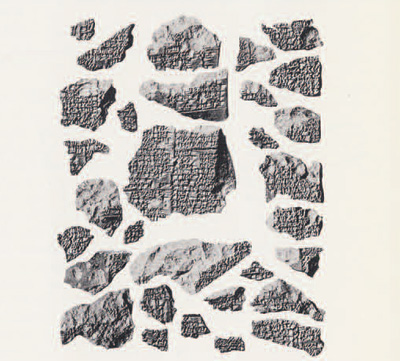

The Louvre has thirty-one tiny fragments of this unique document, the original size of which is uncertain. The largest of these fragments is about an inch square. Small as it is, this fragment contains the remnants of more than thirty lines of text, and some six to seven times as many signs as an ordinary cuneiform tablet. The remaining thirty fragments are all much smaller. About half of them are tinier than the paring of a finger nail, but even some of these contain remnants of several lines of writing. All in all, it is not unlikely that in its original state, the Louvre document contained several thousand lines of text, far more than any cuneiform tablet or prism as yet unearthed.

To judge from its extent remains, the Louvre document was inscribed with an entire cycle of laments revolving about the Sumerian goddess of love, a deity who sparked the imagination of men all over the ancient world: Venus to the Romans, Aphrodite to the Greeks, Ishtar to the Babylonians, she was celebrated in Sumerian song and hymn, myth and ritual, under the name Inanna, “Queen of Heaven.”

The microscopically written laments on the Louvre document probably fall into two major groups. In the one, the goddess mourns the destruction of her temples throughout Sumer. For in the centuries immediately preceding and following 2000 B.C., Sumer suffered several catastrophic and devastating invasions, which left bitter and painful memories. So much so, that the Sumerian poets were moved to create a special literary genre, the “lamentation,” forerunner of the Biblical Book of Lamentations, to mourn and bewail Sumer’s sorry plight. Not a few of these laments were put in the mouth of Inanna, who, not unlike “Rachel weeping for her children,” was said to wander around Sumer bemoaning the loss of her people, cities, and temples.

The other group of Inanna laments concerns the death of her lover and husband, the shepherd god Dumuzi, the Biblical Tammuz. But hereby hangs a tale told in a Sumerian myth, which shows that the Sumerian goddess of love was ambitious, aggressive, vindictive, and cruel.

In the myth, Inanna, although well aware that she was acting counter to the divine laws, descended to the Nether World in order to become “Queen of the Nether World” as well as “Queen of Heaven.” Once there, however, she was put to death by the queen of the lower regions whose position she had wanted to usurp. Or, as the poet puts it:

“She fastened her eye upon her, the eye of death, Spoke the word against her, the word of wrath, Uttered the cry against her, the cry of guilt, The sick woman [Inanna] was turned into a corpse, The corpse was hung from a nail.”

Luckily for Inanna, however, Enki, the Sumerian god of wisdom came to her rescue and had her revived with the help of the “food of life” and of the “water of life.” But though Inanna was alive once again, her troubles were not over. For it was an unbreakable law of the Nether World, “the Land of No Return,” that no one who entered its gates could return to the world above unless he produced a substitute to take his place, and Inanna was no exception. She was indeed permitted to reascend to the earth, but only in the company of seven heartless demons, who had instructions to bring her back forcefully if she should fail to provide another deity to take her place. Several gods, fearing that they might be the intended victims, saved themselves by prostrating themselves in dust and ashes before Inanna. But Dumuzi, Inanna’s husband, was too proud to grovel in the dirt before his spouse; instead, “he put on a noble robe, sat high on his seat.” This so enraged Inanna that she turned him over to the demons who carried him off to the Nether World, never to return.

But Inanna must have lived to rue her hasty, cruel act. Forever after, according to the Sumerian poets, she wandered over the land bewailing the death of her lover and husband in poetic words, bitter and poignant. It is not improbably that a number of these laments were inscribed on the Louvre document.

Typical of the phrasing and contents of the Inanna laments, is the following broken passage from the large fragment of the Louvre document, which is restorable and intelligible at least in part:

“Oh, her heart! Oh her heart!

Lo! Lo! Oh her heart! Oh her heart!

My Queen, Oh her heart! Oh her heart!

Inanna, Oh her heart! Oh her heart!

The princess, her heart cries out in tears,

Her heart cries out in tears and wails,

Like the stall, her destruction…Her heart…Her heart…For the might (?) one…

The stall is destroyed…”

The Louvre document was excavated some eighty years ago in the ancient city of Lagash where the French conducted the excavations which in a sense discovered the Sumerians, for here were found the first important Sumerian monuments, as well as over a hundred thousand Sumerian tablets and fragments. Because of the minuteness of the signs and its fragmentary condition, the Louvre piece has remained unpublished all these years. Since I have devoted practically all my scholarly career to Sumerian literature, Messieurs Andre Parrot and Jean Nongayrol, the curators of Oriental Antiquities in the Louvre have generously permitted me to make a thorough study of the document for future publication in the Revue D’Assyriologie, a French journal devoted to cuneiform studies. It will add little that is new and revealing about Inanna and her tears and fears. But, perhaps, that may be all to the good–to judge what we already know about the not too lovely Sumerian goddess of love.