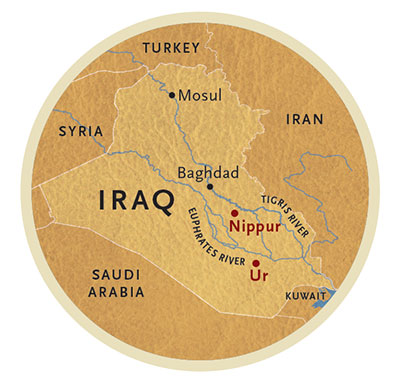

Modern cities have neighborhoods, shops, factories, religious centers, and cemeteries. They have transportation networks along streets and alleyways, and drainage and sewage systems to carry away waste. Cities also have large and ornate public buildings, typically for city administration and religious observance. All of these elements were paralleled in ancient Mesopotamian cities such as Ur and Nippur by 2000 BCE, and most are in evidence much earlier.

Life today may be faster paced, but the overall concerns have not really changed. We all need housing and food, work and leisure, family and friends.

We are intimately familiar with our modern daily lives and we might think them too dull for future scholars to investigate. In reality, they are full of nuance and interest and, by comparing our lives to those of the past, we uncover extraordinary similarities that help us to identify with our ancient ancestors.

So, what was daily life like for an average person in a Mesopotamian city 4,000 years ago? Because the development of the city meant expansion in work specialization, there were a variety of jobs and different daily routines. Farming did not disappear with the rise of cities, but urban dwellers became less involved in raising their own food and more involved on earning it through wages or rations. Without having to spend time growing food, they could concentrate their activity in new fields of industry, commerce, or administration.

Work and Play

In order to support an expanding population performing large numbers of jobs, farms outside the city had to increase production. This meant, in southern Mesopotamia at least, that canals had to be dug to bring more water to the fields. Just as in modern cities, a labor force was essential. Cuneiform texts sometimes tell us the names of the members and supervisors of canal digging crews, as well as their payments. Even though it seems anachronistic, wage labor was in place long before coinage was ever struck. We have clear evidence of it by 1800 BCE, but it likely occurred much earlier, possibly a thousand years earlier.

As cities expanded, builders came into high demand. Canal digging provided huge amounts of mud that brickmakers formed into bricks that builders then used in construction. The king was seen to be the chief builder, responsible for major buildings and expansion in the city. In a groundbreaking ceremony, he brought in the first basket of bricks for temples and palaces. He also had his name stamped into the bricks themselves. Most bricks, however, were less grandiose, and, while they dried in brick molds, they sometimes received more humble markings—misplaced footsteps and wandering dogs being the primary culprits.

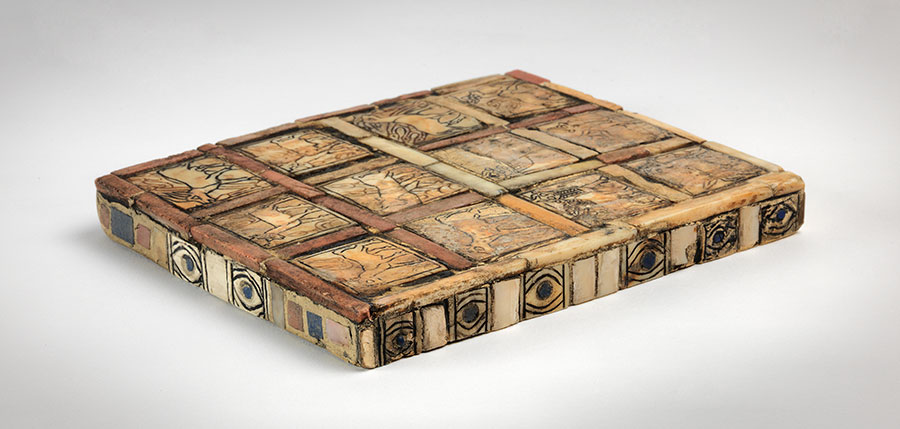

Secondary markings on bricks provide a glimpse into everyday life in the city. We can easily imagine a brickmaker cursing the dogs that ran through the drying mud or a bored builder doodling marks on a baked brick. In fact, a few ancient Mesopotamian bricks have been found with the outline of a game board scratched onto them. The outline takes the same form as the much fancier, inlaid game boards found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. It represents a widespread game played by Mesopotamians, similar to backgammon. Builders probably carved the brick boards to play on while awaiting instructions for their upcoming tasks.

Just as today, then, daily life involved both work and play. Apart from the evidence of board games and gaming pieces, archaeologists have also uncovered toys, such as clay model boats that could be pulled along the ground. More elaborate model chariots with clay wheels, the wooden axles of which have long since deteriorated, have also been found, along with many animal and human figurines that may have been dolls. Children likely played with all of these miniatures in imitation of the adult life they saw around them.

Museum Object Number(s): B16461

Museum Object Number(s): B16216

Religion

Miniature clay animals, vehicles, and furniture have also been found in religious contexts. These may not have been toys, but representative offerings to the gods. Of course, the specifics of a religion may be difficult for an outsider to understand, but some form of ritual is important to all people, and ancient Mesopotamians were no exception. Many Mesopotamian houses had their own private chapel complete with incense chimney and altar. There were also neighborhood shrines to local deities and major temples to the primary deities of the Sumerian pantheon.

Each city had its own patron god. At Ur it was Nanna, the moon god, while at Nippur it was Enlil, chief of all Mesopotamian deities. Temples dedicated to these gods might not be accessible to all people at all times, but there were lesser deities and shrines to help the common people. Minor deities are often depicted on cylinder seals, where they are shown leading the seal owner into the presence of a major deity. People curried favor with many gods, dedicating objects or food offerings at shrines in hopes of gaining otherworldly protection, while also discussing local issues with their neighbors and priests.

Priests and priestesses managed the cult of particular deities and played an important, specialized role in the city. At Ur, the most powerful of them all was the entu priestess. She maintained the temples and rituals of Nanna and his consort Ningal, the patron gods of Ur. The position of entu was usually occupied by the king’s daughter. The entu priestess around 2300 BCE was Enanatuma, the daughter of King Sargon of Agade. Apart from managing the cult of the primary deity at Ur, she wrote and collected hymns to the goddess Inana that were still being read and copied down more than 1,000 years later. She is the first person whose name is directly associated with having created a written work, making her the first named author in history.

Entertainment

Ancient Mesopotamians created some of the first written literature and poetry in the world. They enjoyed music as well, as shown by the impressive stringed instruments found in Ur’s Royal Cemetery. But clay models of lyres and plaques showing people playing flutes and small stringed instruments tell us that music was not solely for high ceremony. People sang and danced often, celebrating life whenever they could.

Museum Object Number(s): B16229

Music requires keeping rhythm and ancient Mesopotamian plaques also show people with drums and rattles. Drums are usually made of perishable materials and are not often found in the archaeological record, but clay rattles are common. These can take many forms, from a hollow clay disk to various animal shapes. Archaeologists are uncertain whether these rattles were used solely for music or also for entertaining children. A hollow clay pig with beads inside might keep children occupied while their mother ground grain to make bread for the family.

Education and Industry

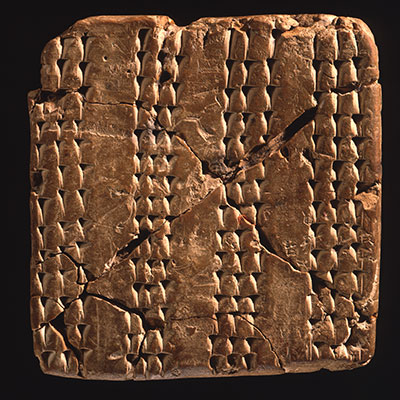

In ancient Mesopotamian cities, it was typically the mother who cared for the children and managed the household. Many children helped their mothers at home and then went on to apprentice in a profession. But some professions required a more scholarly education and formal schooling was a part of the ancient city. The children who were to become scribes, for example, would practice writing by impressing repeated cuneiform characters on clay. They would then move on to copying literary passages and even mathematical problems. Writing was very important for the administration of the city and of commerce, just as it is today.

Worshipping the Gods

This lapis lazuli cylinder seal depicts a lesser deity leading a female worshipper into the presence of a major deity. Cylinder seals functioned similarly to signatures today, allowing a person to roll their sign across a wet clay tablet to identify themselves.

Museum Object Number(s): 31-17-19

The Sound of Fun

Clay rattles were common in ancient Mesopotamia and were probably used to entertain children. The balls inside the rattles are revealed in modern x-rays, as seen here. Rattles come in many shapes and are most often found in domestic contexts. The pig comes from Diqdiqqeh, where it may have been manufactured.

Museum Object Number(s): 38-13-516 / 31-43-464 / B15706 / B2853

It was by no means exclusively men who learned to write; many female scribes are attested. Additionally, women, along with children, worked in the textile industry. Cloth and finished garments—made from the wool of sheep raised outside the city—were extremely important exports. They were used in long-distance exchange to provide the resources that Mesopotamia lacked, such as metal and stone. Making them required a large workforce. Unfortunately, since cloth is perishable, very little physical evidence of this massive industry survives. Weaving implements such as spindles and spindle whorls are found, however, and the textual record attests to the enormity of the overall task. Tablets indicate that around 2000 BCE as many as 10,000 women were active in the weaving industry in the region of Ur, and up to 15,000 in the region of Lagash and Girsu.

Other industries were equally intense. Many, such as firing pottery and smelting metal, created so much smoke that they were located well outside the city. At Ur, the main industrial center was at a suburb known as Diqdiqqeh, about a mile to the northeast of the city wall. Artifacts found here—such as molds, test carvings, tools, and weights—attest to manufacturing and commerce.

Museum Object Number(s): 53-11-103

Museum Object Number(s): B6043

Museum Object Number(s): B14888

Commerce

Although woven cloth, finished garments, and other items were exchanged for resources far away from Mesopotamia, the commercial system was much more complex than barter. In fact, a clear concept of abstract money and physical currency existed in Mesopotamia by 2500 BCE. Even though coinage as we know it would not be created for almost another 2,000 years, raw materials and finished objects, even sheep and houses, were already being evaluated in silver by weight 4,500 years ago. The unit of weight was known as the shekel, from the verb shaqalu, meaning “to weigh out,” and this unit in southern Mesopotamia was equivalent to 8.4 grams.

Mesopotamian merchants carried their own sets of weights and compared them with the weight systems of neighboring regions in order to conduct international business. They also loaned out silver at interest for local purchases like houses, and they financed large-scale shipping over long distances. Law codes, such as the famous Code of Hammurabi, dated to about 1750 BCE, set maximum interest rates and decreed punishments for using false weights.

Ur’s Ancient City Planning, ca. 1900 BCE

Area AH at Ur consists of more than 50 buildings and held roughly five neighborhoods centered on local chapels. Texts and seals found in the houses often tell us names of the inhabitants. This map highlights three people who lived in Area AH and the chapels that anchored their neighborhoods.

The average person would not have had much, if any, silver. The standard pay of a laborer around 1800 BCE amounted to only 1/4 shekel (2.1 grams) of silver per week, about the weight of a modern U.S. dime. But there were equivalencies—one shekel of silver was worth one GUR of grain, about 300 liters. This was the unit in which laborers were paid—a day of work would result in 10 liters of grain, from which the family’s bread could be made.

Daily Routine

So, the daily routine of ancient Mesopotamians around 4,000 years ago was rather like many of ours today. Men and women got up, ate breakfast, and went to work. That work might have been building, digging, metallurgy, pottery, carpentry, weaving, tending to ritual observance, writing, or buying and selling. Although many of these jobs are largely mechanized in modern times, we still see them in our cities. A worker might have a bit of time in the day to play a quick game with a friend or stop off at the local chapel to discuss neighborhood issues, then, after work, go home for dinner with the family and probably a bit of music or story-telling before going off to bed. Sounds pretty familiar.

Discovering the Royal Game of Ur

Leonard Woolley found the remains of shell inlaid game boards, along with disk-shaped game pieces and four-sided dice, in a few of the royal tombs at Ur. All of the boards had a distinctive notched shape, and this same form has been found carved onto bricks. It has typically been called the “Royal Game of Ur,” but even though royalty had the finest boards, commoners played the game too.

Luckily, a much later cuneiform tablet tells us how at least one version of the game was played. The board consists of a square made of 16 places joined to a rectangle of 8 places. The notch created by the join is where pieces enter and leave to complete a circuit. The game is a strategy race, essentially a predecessor to backgammon. Each player attempts to complete a circuit with all of their pieces while also trying to block or disrupt their opponent’s circuit.

Museum Object Number(s): B16742

Museum Object Number(s): B16742

William B. Hafford, PH.D. conducts research in the Penn Museum as a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Near East Section.