On September 29,2000, John Johnson of the Chugach Alaska Corporation arrived in Philadelphia to take formal possession of ancestral Eskimo human remains and grave goods from Prince William Sound and Kachemak Bay in the collections of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. This was a profoundly significant experience for him since he was finally fulfilling one of the central wishes of his elders. They had entrusted him with the weighty responsibility of locating their ancestors in museums throughout the world and returning them home. After the transfer of ownership, he escorted the remains back to Yukon Island,Alaska where they were baptized under the Greek Orthodox Church and buried in an unmarked, mass grave. This ceremony was the denouement of a lengthy ten-year process, initiated in 1990, just prior to the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

These human remains and grave goods were originally excavated by Dr. Frederica de Laguna in 1931 and 1932, as part of a University Museum-sponsored research project, focusing on the prehistory of the Chugach Eskimo people. This research was crucial in defining the Kachemak Bay Eskimo Tradition (1880 B.C.–1100 A.D.).

The collections contain over 6,600 artifacts including hunting, fishing, and manufacturing tools; household objects; and items of personal adornment. In the 1930s, it was common practice for anthropologists to excavate “abandoned” village sites. Cemeteries were especially valued since burial practices were regarded as important indicators of cultural identity. De La guna’s research was conducted under a Federal permit, and with the assistance of Native workers, and thus was entirely consistent with the best anthropological practices of her times.

Today, there is a new appreciation of the legal rights and religious values of Native peoples due in part to the Civil Rights Act (1964), the American Indian Movement (founded in 1968), the Indian Civil Rights Act (1968), the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978), and now NAGPRA (1990). Since the 1960s, Indian activists have patiently asserted their rights and interests in the proper and respectful treatment of Indian human remains. As a result, it is now broadly accepted that the intentional excavation of Indian burials and inadvertent discovery of burials during commercial development projects must involve consultation with appropriate descendant communities. In addition, it is increasingly accepted that Indian peoples have a legitimate interest in the disposition of ancestral Indian remains in museum collections. NAGPRA is thus broadening American anthropology by requiring the profession to confront its colonialist past as a means of envisioning a new and more inclusive future.

What is NAGPRA?

NAGPRA is the popular acronym for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (PL 101-601), passed into law on November 16, 1990. Basically, the law provides a legal mechanism for federally recognized Indian tribes, Native Alaskan corporations, and Native Hawaiian organizations, to make claims for human remains and certain categories of objects held by museums and other institutions that receive Federal funding. Four categories of objects are identified in the law: associated funerary objects, unassociated funerary objects, objects of cultural patrimony, and sacred objects. The legal definitions are listed in the sidebar.

Prior to NAGPRA’s passage, many museums and professional archaeological organizations actively opposed the legislation. They argued that tribes would empty museums of their collections, making it impossible to mount exhibitions and conduct anthropological research. There is, to this day, a vocal contingent of scholars who find NAGPRA to be misguided and would like to see it repealed. But despite dire predictions, NAGPRA has not meant the end of anthropology or museum studies. It simply requires that anthropologists develop their research projects in ways that acknowledge the rights and interests of Native American descendant communities. Significantly, it offers new opportunities for establishing mutually beneficial relationships between museums and tribes.

The popular characterization of NAGPRA as representing an intractable opposition between science and religion fails to acknowledge the historical and political context of Indian peoples in the United States. NAGPRA must be understood as part of a unique body of legislation known as Federal Indian law. In that context, NAGPRA finally recognizes tribal rights of self-determination in regard to the control of human remains, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. With regard to other much larger issues, however, American Indians live today under competing doctrines of legislation that give them only partial sovereignty within the United States. Similarly, repatriation and reburial have long been topics of concern outside the United States, particularly among indigenous peoples in colonial contexts such as Australia, New Zealand, South America, and Africa. New national and state laws in these countries, based upon the NAGPRA precedent, may well emerge.

Implemenation of NAGPRA

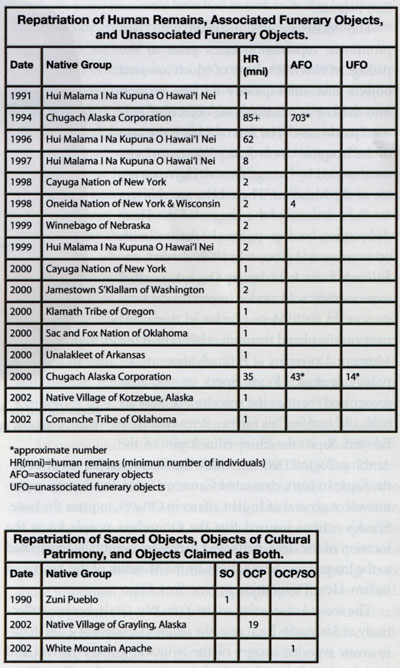

“Bottom Chart: Repatriation of Sacred Objects, Objects of Cultural Patrimony, and Objects Claimed as Both”

The Museum is working assiduously to implement NAGPRA and has established a Repatriation Office and a Repatriation Committee to assist in the compliance process. All claims are submitted in writing to the director who forwards them to the Repatriation Office where they are evaluated for completeness. Viable claims are then brought forward to the Repatriation Committee that makes recommendations to the director. In the case of human remains and associated/unassociated funerary objects, the director is authorized by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania to make repatriation decisions. However, in the case of objects of cultural patrimony and sacred objects, the Trustees retain the right to review each case and render a judgment.

The Museum has mailed over 500 letters to federally recognized tribes,informing them of our holdings and extending invitations to consult with us on these collections. As of 2002, 30 formal repatriation claims, seeking the return of human remains and/or objects defined by the law, have been received and 21 repatriations have been completed. However, because there is no time limit on NAGPRA and because tribes are entitled to make multiple claims, we expect this number to increase, as tribes become more familiar with the law and reprioritize their needs.

The Museum has also established a state-of-the-art web site, with a link to our NAGPRA program, to communicate our repatriation efforts to the public and to tribes (see www.museum.upenn.edu).

Ancestral Human Remains and Associated and Unassociated Funerary Objects

From the Museum’s experience and as seen nationally, it is clear that the majority of tribes are concentrating their efforts on the repatriation of human remains. They are seeking to “bring their ancestors home.” For John Johnson, the reburial of his Chugach ancestors at their traditional cemeteries is crucial so that his “elders will once again have peace of mind in knowing that these significant historical places will be made whole again.” For Edward Ayau, of Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’I Nei, the reburial of Native Hawaiian ancestors is part of a process of healing the devastating toll that colonization has wrought upon Native Hawaiian cultural identity.

The Museum has repatriated approximately 207 sets of human remains to 12 tribes. The largest repatriation has been to the Chugach Alaska Corporation of approximately 120 human remains removed from Prince William Sound and Kachemak Bay. Approximately 85 remains were repatriated in 1994, and an additional 35 human remains were repatriated in 2000. The second largest set of 73 remains was repatriated to Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’I Nei over a period of eight years. The first repatriation was of an infant mummy, collected in 1893 from a cave in Hanapeepee Valley in Kauai, in August of 1991. In November of 1996, an additional 62 Hawaiian remains were repatriated. Eight more remains were returned in October of 1997, and a final two remains were repatriated in September of 1999. All of these remains were part of the famous Samuel G. Morton Collection that was officially transferred to the Museum from the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1997.

In addition to the human remains, the Museum has repatriated 750 associated funerary objects and 14 unassociated funerary objects. The majority of the associated funerary objects were glass beads repatriated to the Chugach Alaska Corporation. One of the unassociated funerary objects was an 8-foot long burial canoe.

Sacred Objects and Objects of Cultural Patrimony

Many tribes are also actively working to repatriate sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony as a means of revitalizing their cultures. Significantly, this is not an attempt to recapture idealized pre-contact lifestyles, but rather is part of a larger process of instructing their youth in tribal values and a means of “bringing the world into balance.”

The Museum was involved with two prominent repatriation cases prior to the passage of NAGPRA, both of which involved objects that subsequently became written into the law as examples of “objects of cultural patrimony.”The first of these is the case of the Iroquois Confederacy Wampum belts once owned by George Gustav Heye, a trustee of the Museum. These belts are charters for the existence of the League of the Haudenosaunee and its political relations with other tribes and groups. In 1899, eleven Confederacy belts held by an Onondaga chief were secretly sold under uncertain circumstances. In 1910, Heye purchased them and temporarily placed them on exhibition at the Museum. University of Pennsylvania anthropology professor Frank Speck immediately recognized them as the missing Six Nations belts and notified his former Penn colleague Edward Sapir, the chief ethnologist of the Anthropological Division within the Geological Survey of Canada. Sapir, in turn, contacted Cameron Scott, the deputy superintendent general of Indian affair in Ottawa, to press the issue. Speck’s actions insured that the Onondaga people knew the location of the “lost” belts, and they were eventually repatriated to the Iroquois on May 8, 1988, by the Museum of the American Indian-Heye Foundation in New York City.

The second case is that of the Zuni War Gods, known collectively as Ahayu:da. Each year, the religious leaders of Zuni Pueblo create wooden images of the twin war gods, Uyuyemi and Maia’sewi, and place them in shrines to protect the village. During the 20th century, anthropologists, collectors and government agents illegally removed the communally owned figures from their designated shrines and sold them on the antiquities market or donated them to museums. The Zuni elders regard the violation of their shrines as sacrilege, and they determined that the return of the figures was necessary to restore harmony and to protect the Zuni community. In April 1978, they began their first repatriation discussions with representatives from the Denver Art Museum. On November 12, 1990, the Museum repatriated one War God to Zuni. As of 1992, the Zuni had successfully repatriated 69 Ahayu:da from 37 different sources.

Since the passage of NAGPRA, the Museum has received three claims for three sacred objects, five claims for 1,300 objects of cultural patrimony, and three claims for 103 objects claimed as both. Of these, the Museum has approved three claims, and denied two claims, with four claims pending and two withdrawn.

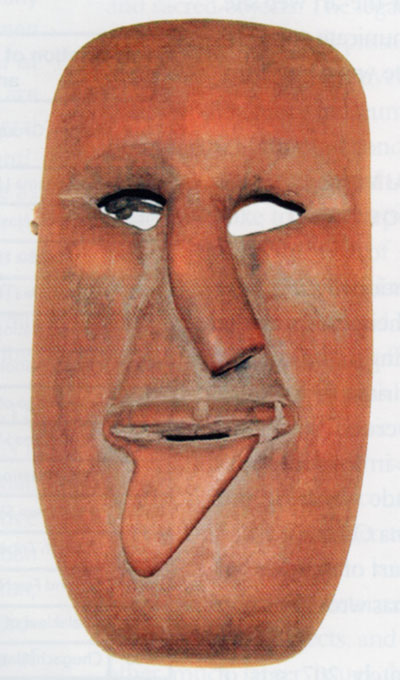

In 1996, the Mohegan Tribe of Uncasville, Connecticut, claimed a wooden mask made by Harold Tantaquidgeon as a “sacred object.” The Museum enjoys a special relationship to the Mohegan people through Frank Speck who grew up on the reservation, and sponsored the education of their revered medicine woman, Gladys Tantaquidgeon, at the University of Pennsylvania. After considerable discussion, the Repatriation Committee denied this claim, on the grounds that it did not meet the legal NAGPRA definition of “sacred object” and offered it to the Mohegan Tribe as a longterm loan. The Mohegan initially declined our invitation, but in 1999, under a new tribal administration, the Tribe contacted the Museum to inquire if the offer of a loan was still standing. A five-year, renewable loan contract was drafted,and on August 30, 2000, Lucy Williams personally conveyed the mask to the tribe. On February 17, 2000, the White Mountain Apache Tribe submitted a claim for one Mountain Spirit (Gaan) headdress as a “sacred object” and an “object of cultural patrimony.” The headdress was on display in the Museum’s “Living in Balance” exhibition curated by Dorothy Washburn, in consultation with Edgar Perry of the White Mountain Apache Heritage Center.

According to the tribe’s NAGPRA representative Ramon Riley, the headdress is “a unique sacred object hand crafted to support the transformation of an individual Apache (Ndee) girl into womanhood” and “once such a headdress has been used by the Gaan spirits it is put away — retired forever as a means for the perpetuation of the healing and harmonizing derived from the ceremony.”

Further, Mr. Riley explained that “the headdress should never have been removed from its resting place, and its repatriation will contribute to the reestablishment of harmony, health, and good will.” The Museum determined that the headdress was an object of central importance to the White Mountain Apache Tribe and that it qualified as an “object of cultural patrimony.” The headdress was repatriate to the tribe on January 10, 2002.

In 1993, Henry Deacon, chief of the Native Village of Grayling, requested information regarding the Museum’s holdings from Central Alaska. This was followed by a claim from Denakkanaaga Inc., working on behalf of the village, for 19 wooden masks as “objects of cultural patrimony” on May 25, 2000. The masks had been collected by Frederica de Laguna in 1935 from a refuse pit behind a collapsed ceremonial house at Holikachaket, an ancestral village of Grayling.According to De Laguna, the masks were once used in the Mask Dance or the Feast of the Mask. The purpose of this ceremony was to insure a continued supply of fish and game, by thanking the spirits of the animals. After careful analysis, the Museum found that the masks were “objects of central importance” to the Native Village of Grayling and could not have been alienated by any one individual. The masks were repatriated on October 26, 2002.

Ongoing Challenges

NAGPRA poses a number of difficult challenges for museums and tribes alike. The most obvious of these is funding. NAGPRA has often been characterized as an unfunded mandate, since there were originally no monies appropriated by Congress for its implementation. The funds that have now been made available are inadequate. In 2000, the National Park Service (NPS) received 112 applications from 76 Indian tribes, Alaska Native villages and corporations, and Native Hawaiian organizations, and 27 museums, for a total request of approximately $6 million. A total of 45 grants, worth 2.25 million dollars, were funded by the NPS, of which only 12 were for repatriation. Most large museums, including this museum, have had to supplement grants with funds from their parent institutions or other sources.

One of the most difficult problems in implementing NAG-PRA is grappling with the language of the law. Its enigmatic definitions and the legal discourse it entails are foreign to most tribal members and museum employees. This is one of the rea sons that some tribes have turned to specialized organizations, such as the Native American Rights Fund, to press their cases. Similarly, many museums have had to seek in-house legal counsel or outside attorneys. Terms like “cultural affiliation,”“alienation,” and “right of possession” pose significant interpretive questions. For example, the process of determining cultural affiliation requires tribes and museums to consider multiple lines of evidence, including geographical, kinship, biological, archaeological, linguistic, folklore, oral tradition, historical or other information, or expert opinion.And yet there is often disagreement over how to weigh these different lines of evidence.

Another issue is identity politics. NAGPRA requires that tribes represent themselves through a relationship of shared group identity that links them to past groups and geographical regions from whom and where remains and objects were collected. However, Indian tribal groups are not static; indeed, like all communities, most have changed over time, sometimes quite dramatically, due to a host of social and political factors, and these changes mean that traditional connections are sometimes tenuous or difficult to establish. This is a particular problem with human remains that are extremely old, as in the case of Kennewick man, as well as in those cases where there may be multiple tribal descendants of a specific archaeological culture.

An unresolved issue is the final disposition of “culturally unidentifiable human remains.” Although the NAGPRA Review Committee was tasked by law to address this issue, it has yet to devise a solution. The current draft legislation is clear, however, in its intent to repatriate all Indian human remains, regardless of their age. For the scientific community, this raises questions and concerns about the future possibility of learning more about important topics such as the peopling of the New World.

On a practical level both tribes and museums are concerned with the treatment of human remains, and objects with consolidants and pesticides. At the turn of the century, it was common museum practice to treat objects made of organic materials, especially feathers and fur, with arsenic as a preservative.

Baskets, for example, were sometimes dipped in mercury. Today, we know that many of these treatments are toxic, and they are no longer used. Unfortunately, early record-keeping was less than adequate, so it is difficult to know, without expensive testing, which objects were given which treatments. This is a special concern for Indian peoples who may want to reintegrate sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony into their ceremonies. Some tribes, such as the Hupa of California, are taking the lead in devising decontamination procedures.

Re-Representing Native Americans

The Museum is committed to understanding and documenting the diversity of Native American peoples in the twenty-first century. This requires not only that we comply with NAGPRA, but that we also represent the character and vitality of Indian cultures to the public in new ways. We are doing this through permanent and traveling exhibitions, publications, new acquisitions, internships, and visiting artists programs.

The Museum currently displays two permanent exhibitions devoted to Native America. In 1986, Susan A. Kaplan and Kristen J. Barsness curated “Raven’s Journey,” which provides an introduction to the worldview and lifeways of the Tlingit, Inuit, and Athabascan peoples of Alaska. In 1995, Dorothy Washburn curated “Living in Balance,”which gives an overview of the Hopi, Zuni, Navajo, and Apache peoples of the American Southwest.

This latter exhibition was prepared with Native consultation and included a children’s component involving an exchange of photographs between Philadelphia-area and Pueblo and Navajo grade schools. In addition, the Museum has an active traveling exhibitions program. In 1998, Sally McLendon and Judith Berman curated “Pomo Indian Basket Weavers, Their Baskets and the Art Market,” which opened at the Grace Hudson Museum, Ukiah, California, and traveled to the National Museum of the American Indian in New York and the Mashantucket Pequot Museum in Connecticut, before being displayed in Philadelphia.

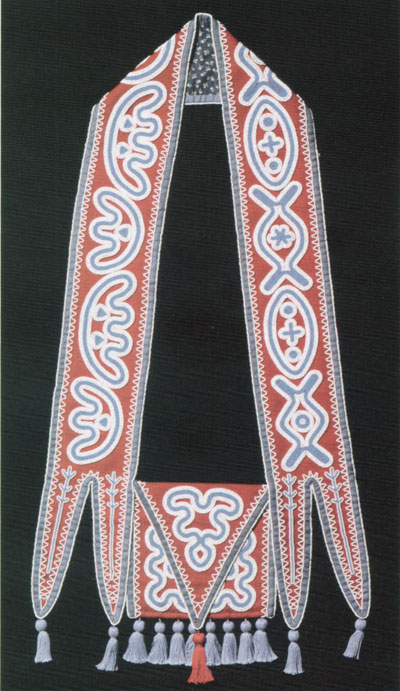

Although funds for new acquisitions are limited, the American Section has made several recent purchases of contemporary Native American art. Some acquisitions have been made as the result of NAGPRA consultations. Raymond Dutchman’s modern carvings, for example, were inspired by 100-year-old masks in the collection that reminded him of events and masking traditions no longer practiced in his own Native Alaskan community of Anvik.

The Museum is an active participant in the National Museum of the American Indian’s Artist-in-Residence Program. Many Native people have a strong adherence to and respect for tradition, innovation, and craftsmanship, and museums that house old collections are uniquely positioned to offer keys to understanding those traditions in support of moderns goals. Choctaw visiting artist, Jerry Ingram, studied the Museum’s collection to gain insight into the style and construction techniques of Southeastern shoulder bags. The information gathered has influenced his work.

Conclusions

Edward Ayau and Ty Tengan (2002) have likened the repatriation efforts of Native Hawaiians to the seafaring legacy of their ancestors. Just as their ancestors made long journeys, which involved hardships and challenges, so too do their people today make long journeys and confront seemingly insurmountable obstacles, as they work to repatriate their ancestors’ remains. Extending this metaphor, we suggest that museums are also embarking upon a long journey to confront their own challenge. This challenge is to redress their history of representing Indian cultures as “primitive,” “static,” and “dying.” We must devise new ways of representing indigenous peoples that acknowledge their vitality, resilience, and ongoing struggles to gain political standing. Because this history is part of a shared American history, we cannot make this journey alone; rather, we must make it in partnership with indigenous peoples. As the Native Hawaiians have so eloquently expressed, out of “heaviness” (kaumaha) must come “enlightenment” (aokanaka).

Objects that, as part of the death rite or ceremony of a culture, are reasonably believed to have been placed with individual human remains either at the time of death or later, and both the human remains and associated funerary objects are presently in the possession or control of a Federal agency or museum, except that other items exclusively made for burial purposes or to contain human remains shall be considered associated funerary objects.

Objects that, as part of the death rite or ceremony of a culture, are reasonably believed to have been placed with individual human remains either at the time of death or later, where the remains are not in the possession or control of the Federal agency or museum and the objects can be identified by a preponderance of the evidence as related to specific individuals or families or to known human remains or, by a preponderance of the evidence, as having been removed from a specific burial site of an individual culturally affiliated with a particular Indian tribe.

Specific ceremonial objects which are needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present day adherents.For more information on NAGPRA and its regulations see National NAGPRA at www.cr.nps.gov/nagpra/.

Ayau, Edward Halealoho, and Ty Kawika Tengan. “Ka Huaka’i O Na ‘Oiwi: The Journey Home.” In The Dead and their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy and Practice, edited by Cressida Fforde, Jane Hubert, and Paul Turnbull, pp. 171 – 189. London: Routledge, 2002.

Thomas, David Hurst. Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archeology, and the Battle for Native American Identify. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Watkins, Joe. Indigenous Archaeology: American Indian Values and Scientific Practice. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira, 2000.