“How do you go about finding a site for excavation?” is a question frequently put to an archaeologist. With the completion of five seasons of work at el-Jib, the ancient Gibeon, James B. Pritchard was sent to Jordan in May to search for another biblical site which the Museum might excavate profitably. In the following pages Dr. Pritchard describes his search and lists the considerations that went into his choice of Tell es-Sa’idiyeh. –Editor.

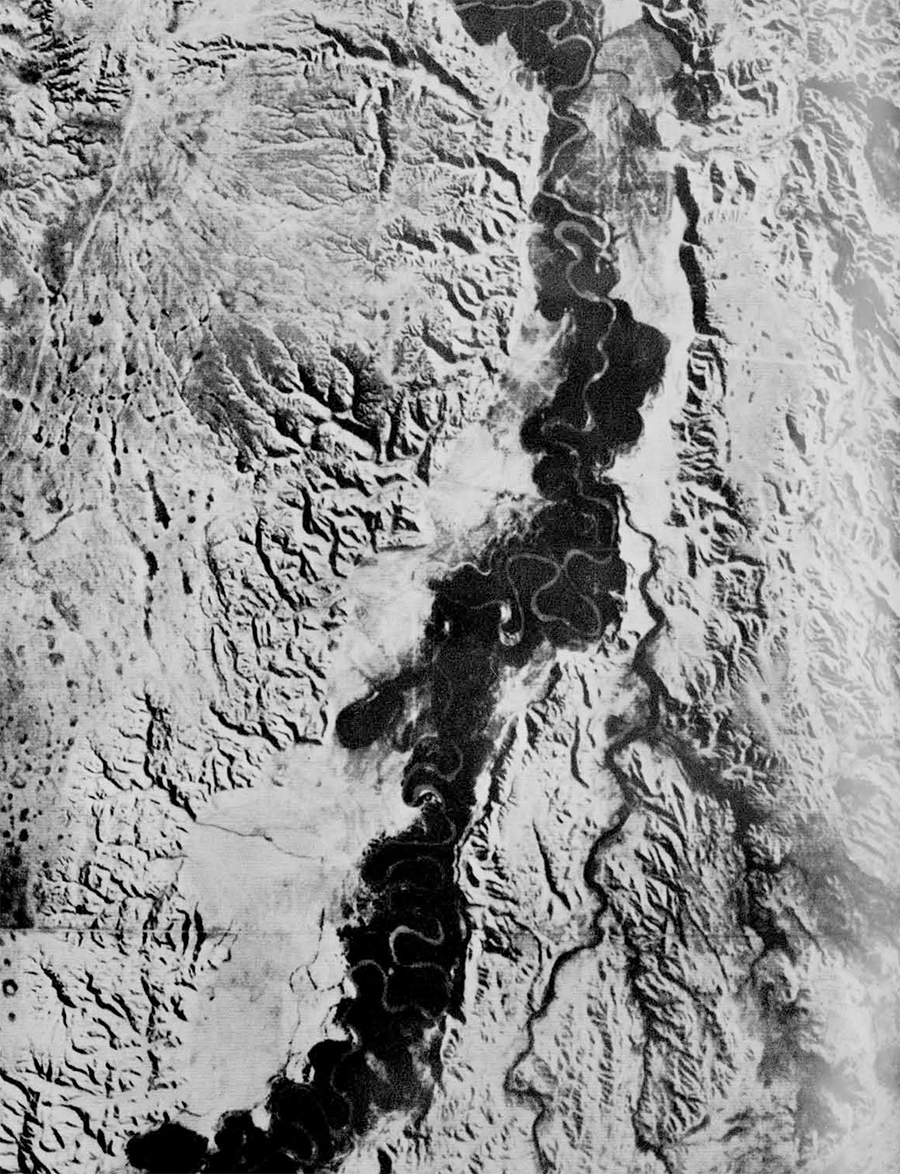

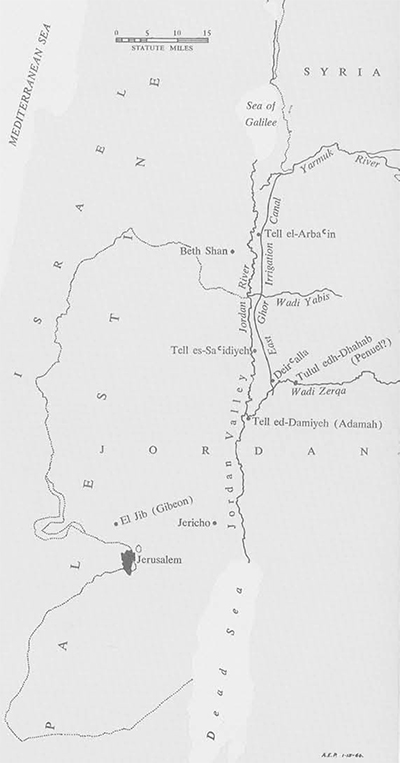

Even before I left Philadelphia for Jerusalem last spring I had become convinced that the fertile Jordan Valley, densely populated in ancient times, held out the greatest promise for supplying new and valuable information on the history of Palestine. If you mark on a map of the Holy Land the hundred or more places where scientific excavations have been made during the past seventy years you will see a conspicuous blank space: the deep, 65-mile-long rift between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea, through which the River Jordan, so rich in history and legend, winds and twists for more than two hundred miles. At the north end of the valley the Museum has excavated Beth-shan; in the south Jericho has recently revealed its 8000-year-long story. Yet the vast area between these two cities has remained to this day an archaeological terra incognita.

The reasons for this neglect are several. For a long time it was believed that the hot and malaria-infested Jordan Valley was unoccupied anciently. No less an authority than George Adam Smith, the famous geographer of the Holy Land, wrote that the mounds which lie along the banks of the Jordan are the “remains not of cities but of brick-fields.” Yet Nelson Glueck, while director of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem from 1939 to 1947, surveyed carefully the east bank of the Jordan and succeeded in placing on the map more than two hundred ancient sites of occupation. What Smith thought to be brick-fields are actually mud-brick walls of houses within cities!

Despite Glueck’s discovery of this cluster of cities lying in the Jordan Valley several hundred feet below sea level in a tropical climate, most excavators have continued to prefer sites in the hill country that can be worked comfortable during the summer, when a staff of academic people can most easily be assembled. The hostility of Arab tribes, as well as heat, has been a deterrent. The Bedouin who have dominated the area along the Jordan until recently are less tolerant of Western archaeologists than are the villagers of the permanently settled parts of the country. Even William F. Albright, an intrepid explorer, was prevented from visiting the 20-mile stretch of the Jordan between the Wadi Yabis and the Wadi Zerqa in the 1920’s because of hostile tribes.

From the Bible one gets clues as to the importance of the Jordan Valley in ancient times. Its fertility is suggested by the remark that Lot “lifted up his eyes, saw that the Jordan Valley was well watered everywhere like the garden of the Lord” (Genesis 13:10). It was the setting for well remembered punitive raids in the time of the Judges, the battle between King David and his son Absalom, and the manufacture of the bronze figures for Solomon’s temple. In this region Jacob is said to have wrestled with an angel; it was the home of the Prophet Elijah and the capital of Israel during the interim between the reigns of Saul and David.

When I arrived in Jordan early in May I had a list of likely sites compiled from maps and the reports of Albright, Glueck, and James Mellaart, all of whom had made surface explorations in recent years. But each possibility had to be checked carefully and appraised in the light of the rapid changes that are today taking place in the settlement of the Jordan Valley, where the construction of a large irrigation canal has already begun to convert thousands of acres of waste land into farms which can grow three crops a year.

Jerusalem proved to be a good base for reconnaissance. The American School there has a working library, where the large sheets of the 1:20,000 Cadastral Survey May of Palestine are to be found, as well as the reports of many archaeological surveys. With references and descriptions freshly gleaned I could drive over the new Point-Four Jerusalem-Jericho highway and in less than two hours walk over a site to check observations on topography and the reports of surface pottery.

After a month of excursions from Jerusalem into the Jordan Valley I became convinced that the most promising mound to dig is Tell es-Sa’idiyeh. Before enumerating its advantages as an archaeological site it may be well to describe other good prospects and to give the reasons for passing them by in favor of the more attractive Tell es-Sa’idiyeh.

The target for our first excursions into the Jordan Valley was Tell ed-Damiyeh, long recognized to be the site of the biblical Adamah. I had three companions: Hamid, the Arab driver of a new Dodge, a policeman–the riots in Jerusalem a few weeks earlier had made me timid about travelling unescorted to out-of-the-way places–and Asia G. Halaby of Jerusalem, a veteran of four seasons at el-Jib.

Within an hour after taking the new road to Jericho we stood at the base of Tell ed-Damiyeh, a beautiful small tell rising about seventy-five feet above the plain. The Bedouin who had settled on part of the site greeted us with the usual hospitality of coffee, a formality which, although costly in time, did provide an opportunity for learning about the neighborhood and its settlers. The land could be rented and there were plenty of willing laborers, we were told. After the four of us had wandered for a while over the top of the tell we spread out on the ground our respective collections of surface pottery, sorting it into piles by chronological periods. It was at once apparent that the site had been inhabited extensively in the Iron I Age (1200-900 B.C.); there were also sherds from the later Iron II and the Roman periods.

There was one disturbing factor, however, about this high mound of debris at Tell ed-Damiyeh: the area of the top of the tell was small, much too limited to have been a city of any great importance in ancient times. Our guess would be that this site, situated as it is at a strategic crossing of the Jordan River, was once a frontier fortress. It was with reluctance that we decided to look for a larger tell.

The timing of our reconnaissance was fortunate, in that we arrived during the final stage of the construction of the East Ghor Irrigation Project, a cooperative enterprise carried out b y the Jordan Government and the US AID Program. Water from the Yarmuk River in the north had already begun to flow through a canal cut through the valley parallel to the Jordan River, and within a very few years the entire face of the valley will be changed. This area, so thickly settled in the Bronze Age, will again be one of the principal breadbaskets of the land.

Early one morning Mr. William M. Shimisaki, an engineer on this project who was interested in archaeology, met us at the construction camp and drove us in his four-wheel-drive Landrover to places along the course of the canal where bulldozers had cut through ancient settlements. By examining the pottery which had been thrown out of the ditch for the canal near Deir’alla we were able to determine in a few minutes the location of the Early Bronze Age occupation of a city for which a Dutch team had been looking for several years. During the course of the day we were able to assign dates to other ancient sites which had not been previously noted.

Tell el-Arba’in is a site that seemed particularly attractive from the descriptions of earlier explorers and Mr. Shimisaki’s report of pottery discovered near it. However, when we arrived there we found it almost completely covered with graves and its edges deeply cut by trenches for the defense of the nearby village. Despite the very attractive remains on the surface of this site the modern cemetery on the top makes it entirely out of bounds for the archaeologist.

Our most difficult expedition was the one to Tulul edh-Dhahab, tentatively identified as the ancient Penuel, where Jacob is said to have wrestled with an angel. The first attempt to reach it ended in failure. Our Dodge was unable to get closer than four miles to the site. A few days later General Karim Ohan, of the Jordan Army, not only offered us the use of his Landrover but he himself volunteered to drive it. After leaving the main road just beyond Deir’alla we picked up a Bedouin guide, Abdul Rahman, and began to follow a rocky track along the Wadi Zerqa. When the way became too rough General Ohan turned into the bed of the stream itself and maneuvered the sturdy army car around boulders and through rapids. After a half hour of amphibious driving we left the car in midstream. Within an hour we reached the top of a magnificent site covered with pottery of the Roman and Iron Ages.

Enticing as this site was we had to decide against it because of the difficult problem of logistics. It would be well nigh impossible to get equipment, food, and personnel to such a remote place. As we turned homeward that day, when the temperature stood at 110 degrees, the General remarked that his next visit to Tulul edh-Dhahab would be in his helicopter rather than by Landrover.

After a month of sifting bits of evidence on the surface of the ground, searching historical records for references to the area, and consulting colleagues, we finally reached a decision. Lying about half way between the Lake of galilee and the Dead Sea, one mile east of the River Jordan, is a large double tell bearing the moder name of Tell es-Sa’idiyeh. From the pottery strewn over the lower level of this double tell it is certain that it was extensively occupied about 3000 B.C., and the depth of the debris would suggest that below the surface lie layers of occupation which extend far back into the ages before the Early Bronze period.

The higher portion of the mound rises about seventy feet above the surrounding plain. It was last occupied in the tenth or ninth century B.C., to judge from the pottery lying on top and from the stub of a city wall distinctive of the time of Solomon. Below the top is a mass of occupation debris that should close the gap of two thousand years which separates the latest occupations of the two levels of the tell.

- In the top picture can be seen some of the cuts which have exposed the ancient cities, thus enabling us to read the history of occupation.

- Three views of the East Ghor Irrigation Canal running along the east bank of the Jordan, which is being built through the cooperation of the Jordan Government and U.S. Aid program to bring the waters of the Yarmuk down the Valley.

- When the canal is completed, the water, taken off in laterals, will make the fertile plain a principal breadbasket for the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

From the extensive area which the tell occupies it is certain that it was one of the most important cities in the Jordan Valley in biblical times. It is probable that the mound is to be identified with one of the important cities of the Land of Gilead: Zaphon, Zarethan, Succoth, or Penuel.

I finished this survey of the valley knowing full well that only by digging could the secrets buried at Tell es-Sa’idiyeh be known. And this will take time, patience, and work. But this much is now certain; it was a large city strategically located on trade routes, supplied with an abundance of spring water throughout the year. People lived within its walls for many centuries, and it lies within an area of considerable prominence in biblical times. Not only is it easily accessible, but its ruins seem not to have been built upon after the time of Solomon or looted by the builders of the Roman and Byzantine periods.