- Stela 5 in situ in 1951, after preliminary clearing bur before excavation. In the course of time, the stela had fallen backward and split vertically and horizontally. Altogether 8 large pieces and 46 chips and flakes were selected for shipment to Philadelphia; the uncarved back was left in Belize. The monument’s exact location was recorded before the pieces were lifted and crated for shipment. The reassembled stela now stands in the Museum’s Mesoamerican Gallery. The University Museum’s survey and excavations at Caracol were carried out jointly with the government of British Honduras, as Belize was then called. When a division of the finds was made, the Musuem took mostly broken monuments because it had the facilities to conserve and reconstruct them. Those that were still intact stayed in British Honduras.

- Logging trucks operated by a local mahogany contractor carried the monuments, secure in their custom made boxes and “pressure-crates,” out of the jungle to loading docks in Belize City. United Fruit Company shipped them on to New Orleans whence they were transferred for their final journey by rail to Philadelphia.

- Slogging through axle-deep mud, one of the Expedition’s eight Land Rover Discoverys maneuvers a tough leg of the 400-mile trek through Belize and Guatemala. The replica were first air-freighted to Belize City, where one of Stelas 5’s replicas was presented to the Belize Government for public display. The Expedition group then set out for a rough-riding journey that carried the remaining replicas to Caracol. Land Rover North America provided the vehicles and sponsored the Expedition, in cooperation with La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation and in consultation with The Nature Conservancy. Additional support was provided by Altitude Marketing, Caterpillar Logistics Services, Coleman, Comsat Mobile Communications, Hella, Magnvox Nav-Com, Michelin, and Warn Industries.

- Flanked by members of the Expedition and Caracol archaeologists Diane and Arlen Chase, the Fiberglass replicas of Stela 5 and Altar 13 rest temporarily at the base of the main acropolis. The site of Caracol was the first stop on the Expedition of Dicovery’s route. Before leaving for Guatemala, the team assisted conserator Glasson in making an on-site cast of another of Caracol’s altars. The replica will remain at the site; the original will be removed to a protected setting under the care of the Belize Government.

- To make molds for the fiberglass replicas, Canadian conservator Gregory Glasson brushed a coat of polyvinyl alcohol-a water soluble, non-staining release agent- directly on the limestone. Subsequent coats of silicone rubber peeled off easily to make the actual molds. Unlike the originals, the fiberglass replicas are relatively light, resistant to the ravages of both weather and acid air, and presumably of no interest to looters. They preserve all the detail of the original carving and will give visitors and accurate view of the monuments in situ. Here, Glasson’s assistant, Research Specialist Christopher Jones, Glasson, and Bill Garrett, president of La Ruta Maya, examine the molded impression of Altar 13 inthe Museum;s Mesoamerican Gallery.

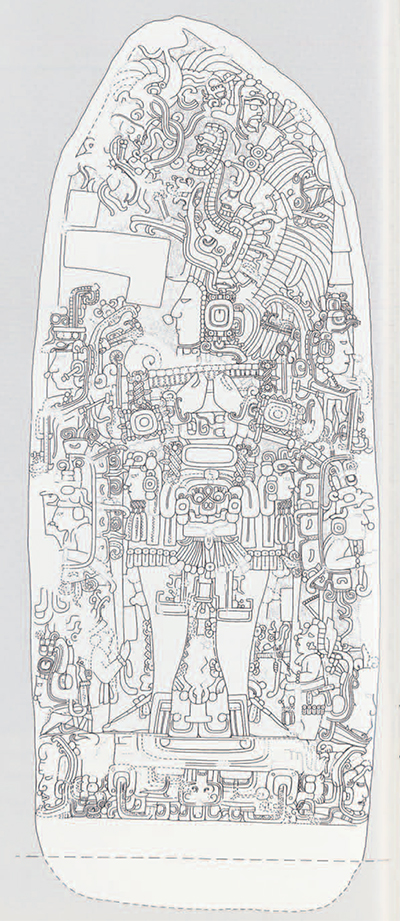

On the left of the central scene, two figures, one standing and one kneeling below a feather wand, gaze at the more elaborately clothed figure to the right, who was probably Caracol’s current ruler. Severely eroded traces of royal titles such as the bacab at the upper right and lower corners of the frame point to the name glyphs of the figure and a possible reference to his parents. The scene is enclosed by a four-lobed frame used in glyphic writing as a symbol both for the completion of a cycle and for the world with it’s four directions.

The altar’s dedicatory date ended one 400-year cycle (Baktun 9) in the Maya calendrical system and began the next (10.0.0.0.0). Its importance of the Maya is comparable to our impending celebration of A.D. 2000. Only a few of the classic Maya centers survived to celebrate this momentous date. Within the next 100 years, monument carving ceased forever throughout the Maya Lowlands.

Stela 5 originally held more the 200 glyph blocks, nearly all of which are missing of illegible today. The name and date glyphs incorporated into the main scene, however, make it likely that the stela commemorates the reign of the fourth known ruler at Caracol, who rose to power in A.D. 599: he was still a ruler in A.D. 617 when Caracol defeated the great center of Naranjo.

In September of 1951. The University Museum received a 20ton shipment of limestone monuments. most of them in fragments, from the ancient Maya site of Caracole, Belize (see Fig 1). Excavated by American Section curator Linton Satterthwaite and presented to the Museum by the government of British Honduras, thee had been cleared, drawn, photographed under natural and artificial light, crated and hauled out of the tangle off jungle growth in which they were found. In Philadelphia the fragments were restudied, reassembled, braced with steel, stabilized, with plaster, and placed on display in the Museum’s Mesoamerican Gallery. Forty-three years later, in January 1994, a return trip took place, not of the original fragments, but of three fiberglass replicas of two monuments-Stela 5 and Atar13.

La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation directed the production and return of the replicas, with a grant from Land Rover North America. The Foundations is dedicated to helping todays Maya thorough conservation of the cultural and environmental assets of their ancient homelands and the promotion of cultural and ecological tourism. La Ruta Maya—the Maya Road—conceptually circumscribes the lands of the ancient Maya and connects them five countries that today occurs that part of Mesoamerica.

The replicas of The University Museums monuments traveled to Belize as one phase in the Foundation’s project “La Ruta Mayan 1994: An Expedition of Discovery.” According to its president. retired National Geographic editor WE. (Bill) Garrett. the treasures of the ancient Maya are endangered throughout their homeland. threatened by damage both unintentional (climate. expanding roots. falling trees, industrial pollution) and intentional (vandalism, theft). Among the most vulnerable are carved limestone stelas and altars. invaluable repositories of cultural and historical information. They are today the only written record remaining from the ancient Maya, whose codices were destroyed by Spanish missionaries in the 16th centers. Removing the originals to museums or other public institutions safeguards them in settings accessible to both scholars and the public. Replacing them with exact replicas encourages “cultural tourism.” which benefits not only the tourist lint also the economy of the regional hoist, whose main resource many he its cultural heritage.

The University Museum intended to continue its research at Caracol, and indeed returned for another season in 1953. By 1956, however, the new discoveries at Tikal eclipsed the Caracole project and absorbed all of Satterthwaites time. Not until the 1980s were full-fledged excavations at Caracole once again undertaken. Under the directorship of Arlen and Diane Chase, archaeologists at the University of Central Florida, these new explorations make it clear that Caracol was one of the largest centers of the lowland Maya and a serious rival to the great city of Tikal. They also make it clear that potential destruction of monuments by natural and human causes has increased dramatically. The preservation of Maya monuments and the assurance of their access to scholars, tourists, and all who care about the past is more important than ever.