At the time of the Spanish Conquest, A.D. 1520-1535, the great American civilizations were those of the Pueblo in the United States Southwest; the Aztec in Mexico; the Maya in Yucatan, southern Mexico and Guatemala; and the Inca in Peru and Bolivia. These cultures had been preceded by earlier ones which we know about today mainly through native legends, illuminated manuscripts (codices), Spanish colonial documents, and archaeological research.

It is generally agreed that the ancestors of the American Indians migrated from Asia by way of the Bering Straits, some 25 to 30 thousand years ago. Apparently they came in several waves, and although they all seem to have shared a Mongoloid racial composition, they had different linguistic affiliations. These early immigrants, who travelled with little more than their weapons and their once domesticated animal, the dog, could hardly have had highly developed social and artistic standards. We must assume, therefore, that American Indian art evolved for the most part on the American continent.

As might be expected, there is a great diversity in art styles throughout the continent. Some Indian groups excelled in weaving or pottery making, others in wood, bone, jade, shell, or ivory carving. Still others specialized in stone sculpture; masonry; bead, feather, or metal work; basketry, or the graphic arts. Many of the Indian groups were geographically isolated throughout much of their history, with the result that they developed characteristic, strictly localized, art styles and techniques.

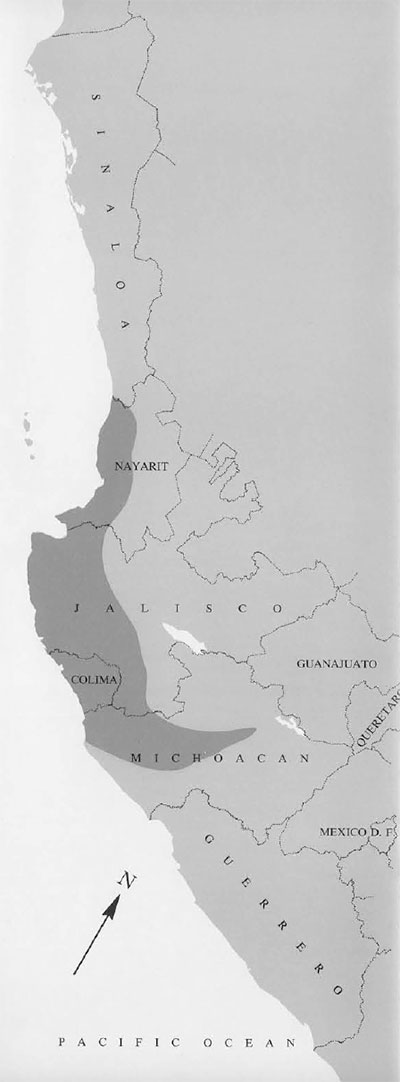

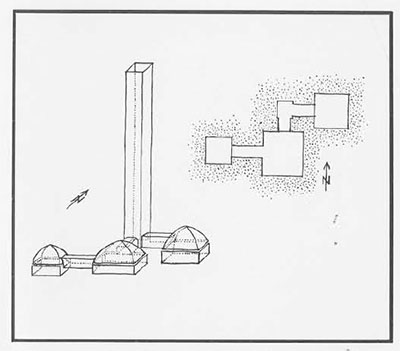

The pre-Columbian inhabitants of western Mexico (today made up of the states of Michoacan, Jalisco, Guanajuato, Queretaro, Colima, and Nayarit) lived in such a state of relative isolation. Unlike the east coast, the central plateau, the Valley of Mexico, and southern Mexico, this section of the country was out of the main stream of civilization, and its art style changed very slowly between archaic (1200 B.C.) and historic times (A.D. 1520). The area is particularly rich in Late Pre-Classic (500 B.C.-A.D. 300) and Classic period (A.D. 300-900) archaeological remains. In the states of Jalisco, Colima, and Nayarit, these are usually found in large bottle-shaped, vaulted, underground chambers with the bodies of the deceased priest or warrior leaders stretched on the floor and surrounded by a quantity of burial offerings consisting of pottery figurines and clay vessels. The creative force behind the production of these figurines and vessels indicates a belief in life after death. The offerings were placed near the body apparently without any special order, some of the figurines standing, others lying face down.

The vaulted tombs, two meters square, were reached by vertical shafts and were at times as deep as sixteen meters below the surface. The clay figurines and effigy vessels found in these underground tombs show an amazing variety of forms and shapes and reflect the secular aspects of life among the common people (as do the Greek Tanagra figurines) in contrast to much of Pre-Columbian art, which was preoccupied with the representation of highly stylized religious and supernatural motives. They dynamic figurines and action groups of western Mexico depict individuals in all possible positions and occupations. Warriors, acrobats, ball players, children, lovers, maternity groups, hunchbacks and individuals with pronounced goiters, drunkards, domestic animals, household pets, pole climbers, mourners in funeral processions, nobles seated on litters, and dancers and musicians, were modeled in an aggressive, forceful, but still realistic and humorous caricature style.

The late Pre-Classic and Classic period solid clay figurines from Colima and Nayarit, which in the past often have been mistakenly ascribed to the Tarascan culture, are particularly interesting. The Milwaukee Public Museum therefore was exceedingly fortunate when it received as a gift from Messrs. Howard E. Moebius and Theodore Eschweiler a small but representative collection portraying groups of Colima style dancers and musicians and several types of ancient Nayarit house models. These Pre-Columbian clay figurines adapt themselves charmingly to an arrangement such as presented here in a west coast Mexican village scene of about 1500 years ago.

In the background there are three rectangular, thatch-roofed houses colored gaily in red, black and white, or black and white with geometric textile pattern designs, over a creamy pink or whitish base. All three have high gabled saddle-shaped roof tops, reminiscent of the high gabled roof tops of the Orient, Indonesia, and Oceania. The house in the center of the picture is the tallest in the group. Six steps lead up to the platform of the second floor. The occupants of this house (four women, three men) and the house on the right (five men), are seated around food dishes (1,2); the stairways and entrances are guarded by fat little dogs. The house on the left, the smallest of the three, (14 cm. high) is occupied by two seated men and one reclining woman (3). Between the two larger houses a figurine group appears to represent either a burial or a curing ceremony (4). A male body is stretched out on the floor and is surrounded by ten seated individuals, six of whom appear to be bare-headed females. The males wear simple headdresses. One of the women holds the head of the body; the other the outstretched legs. One of the mourners, as an expression of grief perhaps, lays his right hand on the left shoulder of the mourning “widow.” There are two food dishes next to the head of the body. These may have been meant to accompany the deceased into his tomb, or to provide him with sustenance on his long journey to the afterworld.

To the left of this group there is a group of dancers engaged in what appears to be a round dance. Four are bareheaded women in skirts, and five are men naked except for headdresses. The male in the center beats a hand drum (5). In the center foreground is another round dance group comprised of three females with pinched headdresses and eight nude males (6). The three male dancers in the center of the circle hold what appear to be percussion instruments in their hands. To the left of this dance group there is a small group depicting three individuals (two nude males and one male in a breechcloth in the center) engaged in some sort of rhythmic linear dance (7). Two of the dancers have their hands on the shoulders of the dancer in front of them. The leader holds a conch shell trumpet to his mouth. In the right corner of the village scene there is a group of four bareheaded females holding hands and seated around a conical object. Undoubtedly they are engaged in some sort of household ritual (8). They are surrounded by three figurines (6 to 10 cm. in height). Two are nude females, seated cross-legged with arms folded across their chests (9,11). One figurine (probably a male) with a peculiar headdress and coffee bean-shaped eyes stands behind a large hollow upright drum and beats it with both hands (10). This little figure is actually an effigy whistle with the blow hole at the headdress. In the left corner of the scene there are three nude females with elaborate hairdos (12, 13, 14); two of them are lying on their backs, tied with three straps to a rectangular stretcher-like bed. Their heads rest on pillow-like objects similar to the stone or clay pillows known from the Orient, Africa, and Ancient Egypt. The meaning of these two reclining female figurines is not clear. They may represent women in childbirth, persons to be sacrificed, or possibly sick persons (epileptics?) awaiting a cure. Similar clay statuettes, sometimes representing infants tied or strapped to beds or cradleboards, have a wide archaeological distribution. They have been noted from as far north as Nashville, Tennessee and as far south as Esmeraldas and La Tolita on the west coast of Ecuador. In Mexico, they are known from the Huaxtec area on the east coast and from the ancient site of Ticoman in the Valley of Mexico where they may have been in use as early as 400 B.C. and where they remained in use during Late Teotihuacan (A.D. 600-900) and Aztec times until the Spanish Conquest in A.D. 1520. These clay female figurines, strapped to boards, or beds, may have been used in magico-religious fertility rites. Today among the Pueblo Indians in the American Southwest, women who desire a child still tend miniature wooden dolls on cradleboards as if they were real. At Cochiti Pueblo in New Mexico, the doll is even buried with the woman when she dies or is hidden with her other belongings.

It is a rare treat for a museum anthropologist to deal with archaeological specimens that so intimately reveal the daily lives of their creators. While in most cases he must go to great lengths to breathe life into the dry bones and pottery of the past, these clay figures from western Mexico speak eloquently for themselves. One can almost hear a murmur of conversation in the little village; hear the barking of the fat little dogs, the wailing of the bereaved, the beat of the drum, and the shuffle of dancing feet. But just as they reflect a brief moment of life from the dim past, these figures so skillfully created by nameless artists also testify to the enduring patterns of peasant cultures throughout the world, from most ancient times to the present day.