The Penn Museum’s excavations at Sitio Conte began in 1940 with an invitation from private landowner, Miguel Conte. Since discovering a Pre-Columbian cemetery on his property in 1927, Conte had encouraged professional archaeologists to help record the history of the ancient Coclé people who once lived there. Associate Curator J. Alden Mason took the lead on the project and, at the onset of the dry season in late January, sailed to Panama City with a budget of $4,000. After establishing a formal contract with Conte and gaining the necessary approvals from the Panamanian Government, Mason set to work on a ten-week investigation.

The five-acre burial site was situated on the banks of the Rio Grande de Coclé. With the hired help of 35 of Conte’s workmen who hauled lumber, gasoline, food, and supplies through the forest by oxcart, Mason established his field camp. In a matter of days, the workmen cleared the campsite and constructed a wooden pier, built two thatched roof cottages with wooden floors, dug the latrines, pitched three tents, set up a kitchen and laundry, and built the camp furniture.

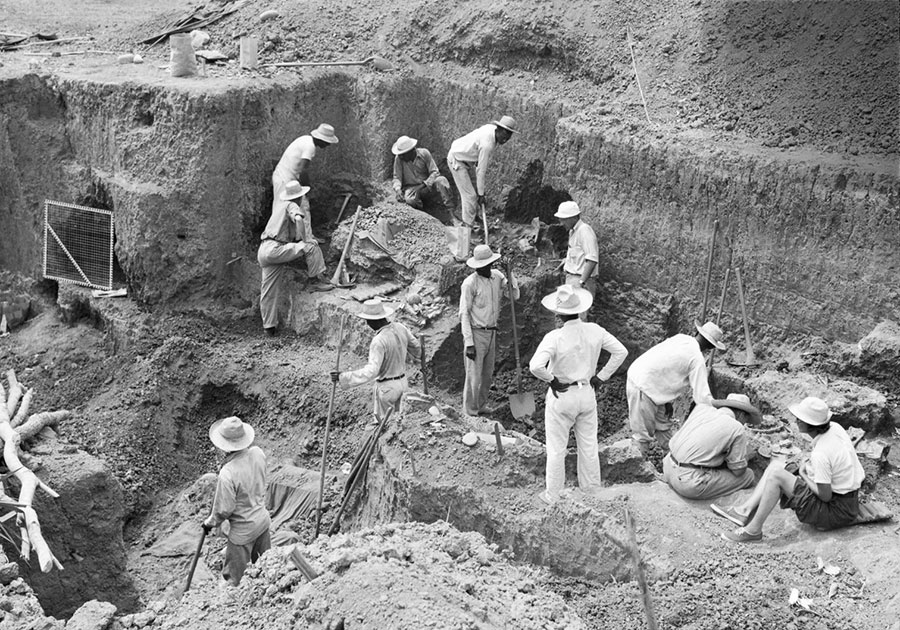

Mason worked closely with colleague Samuel Lothrop of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum who had dug at the site for three seasons in the 1930s. With Lothrop’s advice, and the aid of nine Panamanian workmen plus a foreman, the team dug two trenches more or less simultaneously. The edge of a burial was found in the first smaller trench. Dug by one or two men at a time over a period of nine days, this trench had a depth of four meters—just above the water table in the dry season. Working with shovels, trowels, and small picks, the team uncovered five human burials and six separate caches of artifacts. Robert Merrill, the project’s surveyor, draftsperson, and photographer, developed a system of excavation and documentation to carefully plot, number, and catalogue objects in space.

The second trench was positioned in the center of the large burial and measured 16 x 8 x 4 meters deep. Dug by eight to ten workmen at a time, this trench revealed a total of 30 human burials and caches. The graves yielded numerous artifacts, but on March 16, one month before their planned return to Philadelphia and just as Mason’s field funds were dwindling, the team discovered a massive burial, which produced the most spectacular finds.

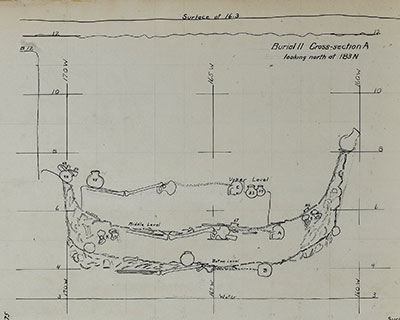

Distinguished by its deep oval and concave bowl shape, Burial 11 contained a large, complex burial of 23 individuals situated in three distinct layers and accompanied by a vast array of grave objects. A thick wall of pottery vessels and sherds lined the north and south walls of the first two layers.

By March 25, the crew had carefully excavated the upper layer, which held eight human skeletons in extended position, face down with heads oriented to the east. Due to high water levels for eight months of each year, the human remains were poorly preserved and difficult to identify. John Corning, the project osteologist, was able to sex and age only a few in this layer, including five adult males and a sixth male of an uncertain age. A necklace of gold bells accompanied the men, and ceramic vessels, agate pendants, stone projectile points, and celts were positioned at their feet.

Less than half a meter beneath the upper layer of Burial 11, the team uncovered an even larger group burial of 12 individuals. Paired with one on top another, nine of these individuals were positioned along the north-south axis with their heads facing east. Three individuals surrounded the central group at the east, north, and south. Corning again had difficulty aging and sexing these remains, but felt confident in his identification of one female, a young male, and a child. Hundreds of painted ceramic vessels and gold objects were associated with these individuals. The most spectacular objects were positioned on the central figure, which Mason concluded was the principal occupant. Thought to be a male, this individual was found with five large gold plaques, an emerald and gold pendant, dozens of gold and stone ear rods, gold arm and leg cuffs, and dozens of gold beads. An adjacent female was positioned on the north side with offerings of ceramics, a gold necklace and ear rods, a garment decorated with gold sequins resembling shark teeth, and a probable apron or waist belt decorated with dog teeth. The entire burial had been wrapped or lined with a layer of bark cloth, and positioned on top of a layer of broken pottery.

Now in early April and working at an all-out pace to beat the coming rains, Mason and his team continued to excavate and found a third and lower burial layer, which included three individuals. The central male rested on his side and was accompanied by one large gold plaque, ear rods, a bat effigy pendant, an array of ceramic vessels, and stone celts.

After completing the excavations on April 8, Mason and his team took another eight days to complete their documentation and wrap up. The workmen quickly back-filled the trenches. They packed three tons of ceramic and stone artifacts allowed by the contract with Conte, which were loaded onto oxcarts sent to the town of Penonome, where they were transferred to trucks and delivered to Panama City for shipment to Philadelphia. After weighing and dividing the gold with Conte, Mason and his crew packed their bags and set sail for Philadelphia.

Lucy Fowler Williams is Associate Curator and Sabloff Keeper of Collections, American Section.