The history of the Department of Peten in Guatemala has unique features when compared to the rest of Mesoamerica. These people are descendants of the Maya of Yucatan; more specifically descendants of the Itza who migrated to Peten traditionally in the early 13th century. Unconquered until 1697 and subject to a delayed colonization program, this area came under Franciscan and Dominican fathers, who undertook its spiritual conquest. But distance from Merida, the strenuous conditions of travel through the tropical rain forest, the feeling of isolation and destitution among the clergy, the poverty of most settlements, and the long years of political unrest caused many settlements to be only periodically served and indoctrinated. Though formal ties had been established, these frontier communities were left unattended for prolonged periods of time. The Itza were later joined by people from Yucatan who had undergone two centuries of cultural and physical mixture. So the spectrum of Yucatan’s population is well represented as a result of several different migrations.

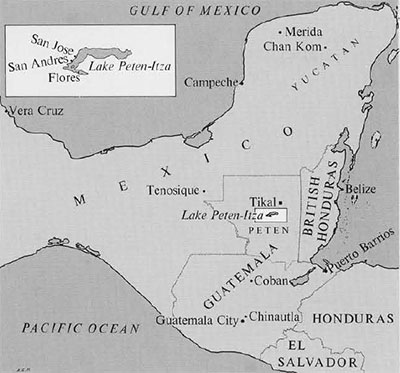

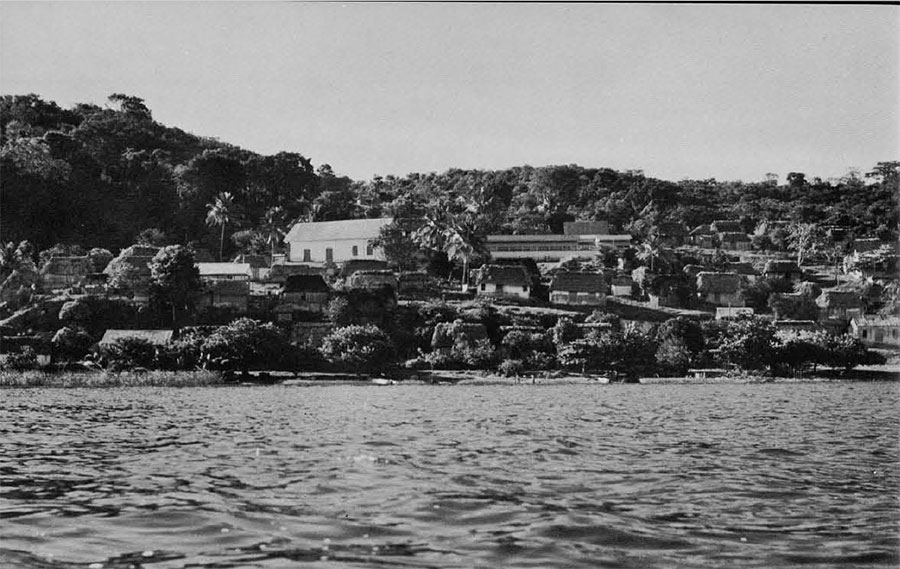

The community of San Jose, located on the shore of Lake Peten-Itza consists of ninety-five families, nearly all of whom have been there for several generations. Five families, however, remember that their ancestors came from Yucatan early in the twentieth century. Practically everyone in the village is Maya, many probably descendants of the early Itza. There is a relationship between this village and specific areas of Yucatan as can be shown ethnohistorically and by such family names as Pech, Moo, Batab, Couoh, Cahuiche, Cocoms, Colli, Tezucum and Zuntecum. today, they continue to speak MAya in their homes. It is similar to the Yucatecan but sufficiently distant so that San Josenos find the Northern Yucatecan accent amusing. The teaching of Spanish, on the other hand, has been severely enforced in school and the learning and adoption of it are surprisingly rapid. Because of their indisputable Maya ancestry, they are known as the Mayeros of Peten, but their clothing and personal ornaments have much in common with their non-Mayan neighbors. In appearance they are indistinguishable from the non-Maya people of the nearby settlements. Their livelihood continues to be derived from shifting agriculture, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and gathering. Cash is obtained by the extraction from the zapote tree, of chicle which they sell to be made into chewing gum. Although contacts with non-Peteneros have fluctuated with time they have been significant because of the variety of traditions they represent. People from Tenosique, Campeche, Merida, Belize, Coban, Guatemala City, and lately Mexico City have migrated to Peten and their cities are places of reference for those San Josenos who have been there and for those who have heard about them. Contact has taken place along trade routes since the time the white man settled there. Natives were sent out to bring in the mail and products of primary necessity including salt, oil, sugar, rice, flour, and kerosene. Furthermore, the operation of lumber camps in the latter part of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries was followed by the exploitation of rubber and chicle, archaeological digging, and geological surveys for oil. Spanish, British, and North American entrepreneurs hired local labor for the exploitation of natural resources.

San Josenos have not stayed behind and viewed all those business enterprises from a distance. They have learned to use and consequently have acquired rapidly such items as an outboard motor for a dug-out canoe or a short wave battery radio, holiday clothing or a modern bridal dress, perfumes, permanent waves, modern medicine, or a planned vacation-style air trip to Belize or Guatemala City. Significant is the fact that a machine is seldom taken for granted; San Josenos are noted for their inquisitive minds and ability both to learn facts and to relate them in a logical analysis of the functioning of the parts of a machine.

The community itself has advanced equipment including a small electric plant, a modern school building, a water storage tank for rain water, and a dance hall (approximately 80 x 45 feet) constructed of modern material flown from Guatemala City at a cost of $12,000 saved from chicle revenue. Moreover, the adoption of Spanish in all official and city dealings, participation in national political parties, and discussion of national or international issues (such as Kennedy and Nixon while they were candidates for the U.S. presidency) are matters which concern the male population and frequently filter down to some of the women. The sophisticated “up-to-date and matter-of-fact” constitute a modern cultural layer which is functional in dealing with officials, outsiders, or businessmen, as the case may be. I found much in common about which to talk, and if a comparison may be permitted, they are more up-to-date than the inhavitants of the Pokomam-speaking village of Chinautla, located only nine miles from Guatemala City, which I studied in 1955-56.

It is interesting to consider that the main portion of their livelihood is derived from the forest. Survival is dependent upon use of the slash-and-burn technique to grow corn, black beans, and fruits, supplemented by hunting, gathering, and fishing. The land is nationally controlled, therefore San Jsenos need only request official permission to exploit the land and its resources. Despite the complications in dealing with the administrative officials, or agencies, all San Josenos have maintained rights to the use of fores land within the municipio. The moment a San Joseno puts on his working clothes, takes a dug-out canoe, his machete, his tump-line, and his dog, one seems to face an inconsistency. In the forest his ideas about nature and man are distinguishably pre-scientific. Mysterious events of the forest do not require an empirical explanation based upon observable facts. The explanation lies in the behavior of the guardian of the forest, the duendes (goblins), wandering souls, the x-tabay (a supernatural being in the form of a beautiful woman), spirits who may appear as fireballs and luminescent birds flying over the lake, gigantic animals enclosed in mysterious caves which produce thundering noises, evil winds which will bring sickness, and espantos (frights) that cause paralysis. The “heavy hours of the night” are avoided because all those things, souls and ghosts, are actively at work seeking to contact human beings in various ways. It is safest to be asleep under a good roof, enclosed by the walls, with doors and windows well shut.

For several months I visited frequently with the most learned man of the community. he had been educated under a well-known teacher from Guatemala City early in the century. Well trained, he became the teacher and secretary of his own and nearby communities. Lately, he has been an expert in law (uisache) and has defended many cases of Flores and other villages in the court of Primera Instancia. His reputation as a “lawyer” is good. His father figured prominently in the 19th century history of Peten, receiving a high military title for his public service. He assisted the governors in the exploration of the forest and helped in revolutionary periods. He was a real Mayero. One evening the community received a wire from Flores. It was for the teacher. The little granddaughter residing in another town was reported seriously ill. Upon his arrival there, he asked for information about his granddaughter. He questioned the mother about the condition of the child, her diet, medicines, doctor’s and herbalist’s prescriptions. Everything was considered, but an explanation for the illness was not found. Why should the child be sick? His daughter-in-law then told him that the night before she had dreamed of the child’s deceased father. There was a sudden change in the grandfather’s gestures. He became tense and anxious “So it is,” he said, “her father’s soul is lonesome and unhappy; he is visiting the household to take the daughter’s soul with him.” It was no longer a matter of struggle between the illness and modern medicine; it was a problem beyond medicine. It was a matter between them and the soul of the father. The appeasement of the father’s soul, his comfort by some formula, would, it was felt, return the health of the child. Devotion to the human skull was promised for the next November 1st.

Most villages in Middle America today hold rituals on November 1st to help the souls of departed relatives. Redfield and Villa Rojas report that in Chan Kom, Yucatan, “all souls of the dead return to earth for annua visit and depart…tables are arranged at midnight…to invite the dead in. Chocolate, bread, and several lighted candles [are placed] on the table…one jicara of chocolate, one piece of bread, and one lighted candle [are] set in [the] doorway for souls with no living kin.” In the Highlands of Guatemala, Catholics of Maya descent prepare themselves for the visit of the souls of relatives on the same date. There are insignificant variations from village to village as to the time, length, and elaboration of the event. A ritual takes place in the cemetery where much food is left for the deceased. Offerings include liquor, cigars, or sweets liked by the dead. The grave is outlined by many dozens of small, lighted candles awaiting the return of the soul. Relatives spend most of the day feasting and exchanging food with each other. At sunset the people feel that the souls will leave, and the women end the event by dramatizing the departure with expressions of grief. As far as we know, no human skulls are used in the Highlands. San Jose, Peten, is the one community where the human skulls are an important part of the ceremony.

Located conspicuously in the left-hand corner of the main church altar stand three human skulls without their lower jaws. Each one is identified by a distinctive geometric mark of gum pasted on the forehead. According to local legend, they have been there since time “immemorial.” The oldest people today remember their grandparents saying that the skulls had been gentes muy finas(fine people), priostes(stewards) but, the add a saber(who knows?). Their actual identity has been lost and there is no old myth to support their meaning and power. The striking thing, however, is that the ritual is now opposed by the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, the people insist on their right to continue having the skulls in the church.

November marks the end of the rainy season. Storms are not so frequent nor so rhythmical as in the previous months. The night of the ritual in 1961 was clear, bringing out the silhouettes of people gathered in the streets. They were patiently awaiting the important hour. The priest had been invited from the nearby town to say a Mass early in the evening, but only a small group of twenty women and children attended the service. A few oung men from the nearby village of San Andres were conspicuous for their boisterousness; they are the “uninvited” guests, year after year. “They are not here for devotion,” remarked a San Joseno, “but for eating and drinking.” The majority of San Josenos do their utmost to be in town on this night, leaving their temporary residences in the forest and chicle camps. The gathering for the celebration would appear to be conducive to the customary heavy drinking; however San Josenos do not drink on this night.

There is an elder in the town ( a prioste) in charge of the organization of the celebration. Early in the day one of the skulls is placed in a newly decorated position on the main altar of the church. The prioste is informed early in the year of the families who are willing to receive the skull in their homes. In 1960 there were nine homes on his list. Among the reasons given by families wishing to honor the skull were illness, an experience which brought the person near to death, the death of a son, desire for protection, devotion, and faith.

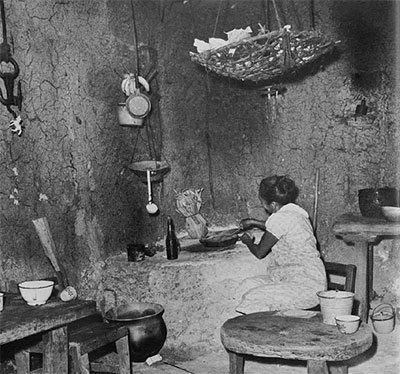

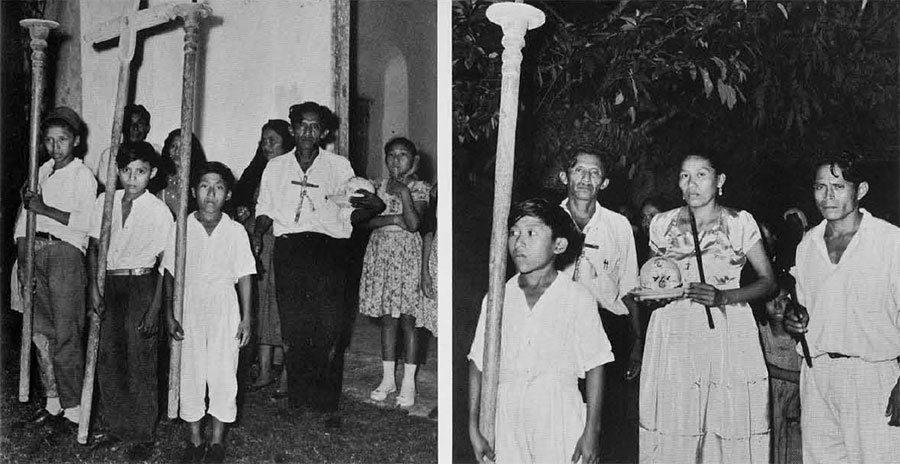

One of the church bells–dated in 1718–announced the departure of the procession from the church. It was nearly midnight. Some of the people in the streets joined in, while others went to their homes or remained behind. There is a belief that when a person joins the procession he must continue until its completion; otherwise he will meet with some form of suffering for his indifference. In the procession of a young man, dressed in Western-style clothes and with a wooden crucifix hanging from his neck, held, cradled in his left arm, the tin plate on which the skull rested. In his right hand, he carried a homemade candle. Three young boys preceded him with a large wooden cross and two tall candleholders. The group of prayer-makers, reciting the liturgy of the church for the occasion, followed them. The party moved slowly through the streets stopping at the patio of the first household on the list. There were relatives and invited friends awaiting them. Everyone was in complete silence. The young wife, dressed in a new silky dress with her hair combed in the characteristic Yucatecan style, walked with her husband from the door of the house toward the man with the skull. They carried long black homemade candles in their hands. The plate on which the skull rested was received by the wife who invited the participants in the procession to follow her into the home. She delicately placed the plate with the skull on a home altar where hot food, candles, and a container with water had been set for the skull alone. This is a hot meal with tamales, bollos, and soup made of pheasants and wild pigeons. For the lonesome souls, without relatives on earth, food is placed outside the house in a solitary place.

The emotion of the group at the arrival was evident. The couple and the guests appeared tense. Informants stated that although one sometimes forgets the relatives and even their place in the cemetery, the arrival of the skull means the arrival of their souls. “One feels weak and like crying,” he added.

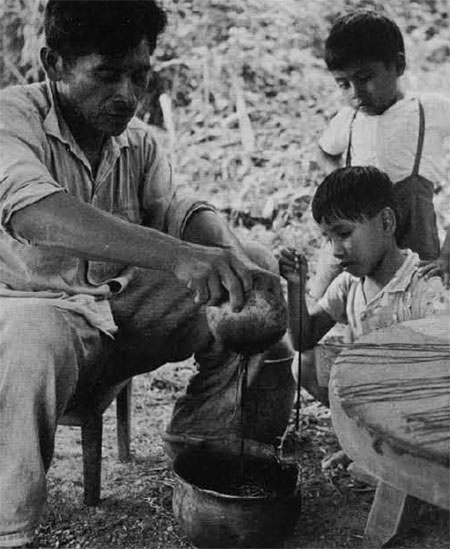

After the household prayers, the special guests of the family were served a small glass of wine, tamales, and bollos made of black corn, and a drink known as atole. The rest of the people were served tamales and atole afterwards. After forty-five minutes, the woman very sadly took the skull from the table for the departure. It was handed to the same leader of the procession. The group, singing a hymn, departed for the second household, where the ritual was repeated.

There are a number of requirements for those directly involved in the ritual. They include specific rules covering the quality of food, the manner of its cooking, the new pottery vessels, the new containers made from the gourd tree, and the candles. The man handling the skull is to have a prayer-maker come to church daily for forty days after the ceremony to pray and to light a traditional candle to the three skulls. Those who promise the reception–in devotion– should not be involved in fights, quarrels, or in sexual matters. To be at peace with the world is a prerequisite for the success of the ritual. Working on this day, or even the day before, has brought many “unhappy incidents” to the lives of several people.

The conclusion of the visiting came about sunrise, when the skull was returned to the church and placed with the other two skulls. The same skull will not be removed from the church for a period of two years. A priest was invited to conduct the Mass of the Souls (misa de los difuntos). Each family sent representatives to request the supplication (responsos) of the priest for the help of the souls of relatives through the church ritual.

While awaiting the hour for the procession with the skulls, there was an opportunity to talk about this costumbre. The statement of a middle-aged man showed the ideological bent. “The skulls,” he said, “were spiritual men of ancient times. My grandfather told me that they were important, and his grandfather said the same thing. They are more important than the saints because the saints are made of wood. The skulls have been human beings and have been alive. They are real bones just as ours are.” A progressive political leader of the village proudly indicated that only San Jose had been left with this unique celebration in the entire Peten and Yucatan.

In the discussion, something of the mythical content of the ritual of the skull was disclosed. The soul (anima) returns to the earth on this night and looks forward to being properly attended. “This we know also from our ancestors. My grandfather used to say that there was once an old man who became very mean and skeptical about the celebration. He went to the church alone the day before the ritual to take care of some repairs and while there, he heard many voices of people talking. No one else was there, but the voices were discussing familiar places and names of people because they wanted to visit them on the night of November 1st. He realized that they were souls. The old man doubted no more.”

There is also the legend of another man who failed to observe the ritual. He ordered his wife not to make new pottery (as is done for the occasion) and to stop any preparation. He did not gather wild bees’-wax for the traditional candle-making, a task of the men. He argued with his wife that the celebration was no longer needed. On the day when everyone was busy with the devotion he went into the forest to work as usual. He returned lat in the afternoon, ate, and after closing the doors of the house, the family went to their hammocks. The rest of the town went on quietly with the celebration. Suddenly he heard loud, strange noises, and out of the confusion someone was clearly saying “What shall I do, and where shall I go?” The old man and his wife realized that it was the voice of a dead son. The husband failed the ritual no more and was very devoted thereafter.

Many more incidents are told of families who reluctantly have undertaken the celebration only to find that because of their poor attitude the ceremonial food has spoiled before it could be presented at the table of the souls. “These are very old cases but illustrate the importance of continuing the ritual,” stated a literate “son of the pueblo” who has travelled to Yucatan, to Belize in British Honduras, and to Guatemala City.

No one can forget the action of a mayor in the ’30’s who prohibited the celebration upon the recommendation of a governor (jefe politico), a ladino from the Guatemala Highlands. The world crisis was affecting the area. Chicle was not in demand. Many families, nevertheless, had promised to receive the skull in their homes that night. There was confusion, but the official order was obeyed. The town was in silence when at the “heavy hours of the night” some people heard the church bells tolling mysteriously but forcefully. A few brave men went outside and experienced something very strange; they reported seeing a multitude of people in a procession behind a human skull. It was like something real, they said, but it was over the calm waters of the lake.

“We have known all along that the celebration is like a law and although we live in modern times, this is not something to be disregarded.” They have deduced that it must be of Maya origin because the Spanish clergy does not approve of it. The clergy is strongly opposed to the ritual. There is the recent incident of a priest who offered as a gift to the community a Requiem Mass at the burial of the three skulls; but the people would not consent to the burial. Said one man, “He requested that we forget this pagan practice. We had no choice but to tell him to leave the skulls on the main altar or to leave town himself. He chose to leave town. The current priest, however, is more understanding. He tells us that he hopes we will forget it all eventually. He does not undersatnd that this antique thing (cosa antigua) cannot be discarded unless one has a reason for doing so. He comes from the land of Spain and does not understand our customs.”

In the many dramatic encounters between the clergy and the natives of the New Spain, it has been evident, as Eric Wolf has said in Sons of the Shaking Earth, that “it is easy to dismember men with cannons; it is more difficult to tame their minds.” The clergy had difficulty in establishing the new religion, and on many occasions it made use of its political power to eliminate what it did not approve. It is uncertain, however, how–and here we quote Ralph L. Roys who has translated numerous Maya documents in his study of the history of the Maya–“Indians from Yucatan began to combine some elements of Christian worship with their old idolatrous practices, but we learn of an Indian of rank of Zotuta by the name of Don Andres Cocom who, about the year 1585, was convicted, not only of idolatry, but also as a perverse dogmatizer and inventor of many new abominations among Indians.” This harsh treatment of the natives caused the de-population of villages. The acuteness of the problem resulted in a re-evaluation of church policy. A Royal Command (Real Cedula) of the 18th century ordered every Spaniard to do whatever possible, in a peaceful way, to bring back the Itza from the forest and get them to live in villages. The clergy became more tolerant of some of the natives’ views.

Donald E. Thompson in his stidy on Maya Paganism and Christianity concludes: “Despite the crosses, saints, and seemingly Catholic prayers, the Maya clearly are not a converted people. As Nock suggests, conversion implies the conscious reorientation of the soul to a new and ‘right’ philosophy. A Prophetic religion such as Catholicism, unlike most primitive religions will, by the nature of its construction, admit no compromise. The Maya have never been fired by a conviction that their old religion was wrong and Catholicism right; they have compromised.” This generalization, I feel, applies also to San Josenos. The use of the skulls, reactions of the people, and the history of the practice provide the basis for future analysis of important historical processes for this area.