A NEW epoch has begun in the excavation of antiquities in Cyprus. In the past the looting of tombs and sacred places was constantly carried on by peasants working hastily at dead of night, or with scarcely less questionable methods by dilettanti and scholars who had no appreciation of how much could be learned by the careful and relentless scrutiny of every step of the process of excavation. As a result the museums of Europe and America contain collections of Cyprian antiquities which are almost entirely undocumented. A growing sense of responsibility, however, on the part of both government officials and of scholars toward these buried records which are inevitably destroyed as they are read, has gradually transformed methods of digging and at last the soil of Cyprus is being studied according to the highest standards of scientific research.

Swedish scholars were the first to realize the possibilities of the application of such methods to the sites of Cyprus, and our own Museum was second in this new field. A brief account of our expedition to Lapithos under the direction of Mr. B. H. Hill was given in the March Bulletin. During the course of the summer, the specimens granted by the Cyprus government arrived at the Museum. For every one of the vases and bronzes sent, which were packed, listed and checked with scrupulous care, the place and circumstances of finding are known. This may seem a simple matter, but in tombs which measure some twelve by fifteen feet, which are so low that an excavator cannot stand erect, and so crammed with vases that he cannot sit down, it is good evidence for the skill of the excavators, that for each tomb there is a large plan, drawn to scale, which pictures every object found as it lay in situ. Even beads the size of a pin-head which had been strung on a cord wound around the hilt of a sword, are duly recorded and preserved.

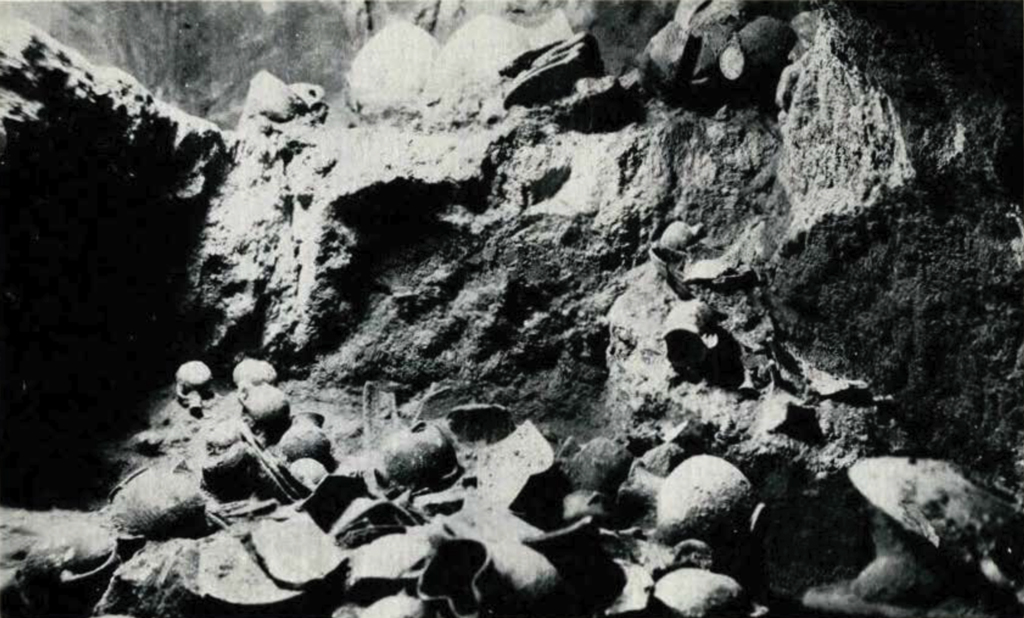

The tombs which contained the greatest amount of pottery were those which date from the early Iron Age in the neighborhood of 1000 B. C. In one of these [Plate VII], the entire contents of which were acquired by the Museum, some one hundred and fifty vases and fragments of others were found, as well as a large number of pots which had been interred at a higher level and had fallen through a collapsed floor into the tomb below. The drawing of the floor of this tomb accounts for every object from either level.

Conspicuous among the vases from this tomb are deep set plates which were found in piles. They have two small handles which are sometimes rounded and sometimes horned. The largest is over eleven inches in diameter, the smallest somewhat over three. These plates are decorated most effectively with geometric patterns in red and black painted on the buff ground of the clay. Circles play a large part in the ornamentation and seem to have been applied while the vase was still on the potter’s wheel. The main design is usually on the bottom of the plate that it might be enjoyed when the plate was hung against the wall. On some plates there are painted lines below the handles which apparently imitate the handles of baskets. A selection of these plates is shown in Plate VII.