It is with regret for the Museum that we announce the appointment of Battiscombe Gunn, lately Curator of the Egyptian Section, to the chair of Egyptology at Oxford University. The Museum, in facing its loss, can but congratulate Mr. Gunn upon his accession to the highest post in his field of study, and express keen hope that his new connection will be in every way agreeable.

Among his many activities in rearranging and rehabilitating the Egyptian Section, not the least was the installation of the Mummy Room, opened to the public for the first lime, within the last fortnight. Before his departure Mr. Gunn prepared the following brief article on the contents of this small yet exceedingly informative gallery. It is followed by a short description on the methods employed in making mummies, by Miss Margaret L. Moon, now Assistant Curator in charge of the Egyptian Section. To the readers of the Bulletin both articles are commended for the light they throw on a perennially interesting (though perhaps some-what gruesome) subject.

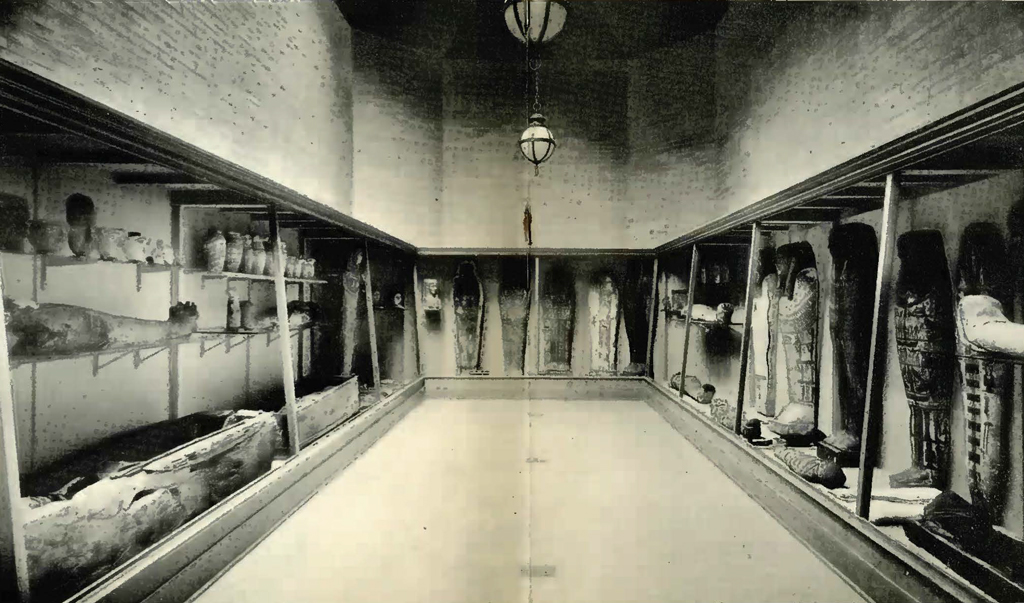

THE scope and interest of the Egyptian Section have recently been greatly increased by the installation of a room devoted to mummies and funerary equipment (Pl. V), and containing a quantity of material which has been in the Museum for some time but which, for lack of space, has not hitherto been placed on exhibition. With very few exceptions the objects in this room belong solely to burials, to the exclusion of objects used in life and afterwards deposited with the dead; the latter may be found elsewhere in the Section.

Of greatest interest are doubtless the mummies. Among those present-as to their mortal part-are the Priest of Amūn, Nebenteru, looking strangely fresh in his white wrappings; the Third Prophet of Mūt, Hapimen, with his dog who was mummified and buried with him; Jehap (Pl. V, left), with well-painted trappings of “cartonnage” (Egyptian cardboard); another man, well bandaged and decorated, who is curtly referred to on his coffin as “so-and-so” (Pl. V, right); the Chief Singer Nespekashuti; and Tanious, a little girl about seven years old. Some heads, hands and feet, torn from mummies by tomb-robbers, have a grisly interest. A series of X-ray photographs of some of the mummies, made by Dr. J. Gershon-Cohen, roentgenologist of this city, is displayed; the prints show how the rays render valuable service to archaeological research by revealing sex and age, pathological conditions, the displacement and absence of bones due to defective mummification, the presence of amulets and ornaments, and other features hidden from view by the thick wrappings.

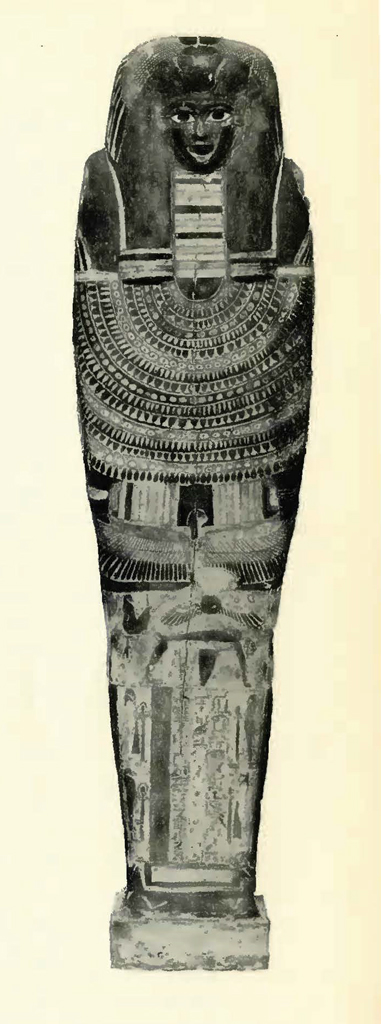

Over a dozen coffins and mummy-cases are shown. Most of them represent their former occupants in human, or rather divine, form, as identified with Osiris, the great god of death and the resurrection. They are brightly painted with copies of elaborate beadwork ornaments, mythological scenes of the Netherworld and funerary gods, as well as hieroglyphic texts stating the titles, names and parentage of the dead, and invoking for them “meals of bread and beer, oxen and geese, wine and incense, every good and pure thing on which a god lives.” Some faces of wood and “cartonnage,” formerly attached to coffins, are included in the new installation; one or two of them have real artistic merit.

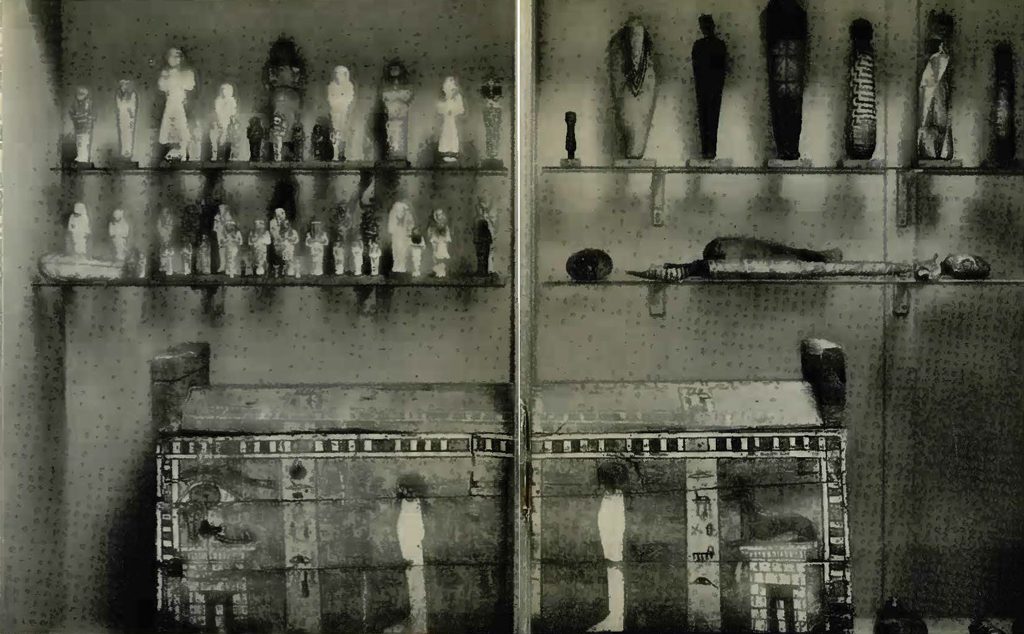

Coffin of a Cypriote, excavated at Meydum; funerary figurines and mummified animals

Museum Object Numbers: 31-27-118A / 31-27-118B

Of the elaborate funerary equipment held to be necessary for the burial of a self-respecting Egyptian, most of the components are here represented, There is a good series of visceral (“Canopic”) jars, with heads of men and animals as lids, in which the inner parts of the body were enclosed after separate embalmment; some wooden head-rests very similar to those used today in Africa and Japan; small, brightly painted memorial tablets (“stelae”), having pictures of the dead man or woman adoring one of the solar gods; a great sheet, over twenty-four yards long when unrolled, which once swathed a mummy; and many specimens of cloth (some very finely woven) from mummy-wrappings of all periods, together with parts of bandages inscribed in ink with magico-religious spells, with illustrations, for the protection of the dead. Two shelves are devoted to a good collection of funerary figurines (Pl. V, above at left), representing the dead with whom they were buried either in their human aspect or as identified with Osiris. Those having the latter form are inscribed with a magical spell in which the dead man commands them to perform for him all the agricultural labors which may, according to Egyptian belief, be assigned to him in the Netherworld. Such figures-“shawabtis,” as the Egyptians called them-were sometimes placed in miniature coffins, similar in every way to full-sized ones, thus emphasizing the identification of the little figure with the man himself; an unusually good specimen is to be seen in this part of the room.

Some adjuncts of burial were used only in certain periods. Such are the curious pottery “soul-houses”-little buildings with rooms and pillared porches, intended to shelter the souls of the dead while they consumed the food-offerings (also of clay) strewn in the courtyards; pottery offering-trays of the same period (about 2200 B. C.), apparently representing gardens, and having offerings and little arbors for the dead; and some wooden mummy-labels of the Graeco-Roman period, which, inscribed with the names of mummies, were tied to the latter to identify them before they were placed in their coffins. The so-called mummy portraits, of which we exhibit two, are limited to the Roman period; these adorned the houses of the persons represented during the lifetime of the latter, and after their death were fastened over their faces, or replaced on their coffins the carved wooden faces of earlier times. Entirely classical in style, such portraits are of importance as being almost the only examples of Roman painting in wax, the utilization of them for funerary purposes having preserved them in Egypt alone. Of the same period are two fine painted plaster heads, also of classical type, from mummies; these, like the portraits, were found in the cemetery of the Egyptian Philadelphia.

A View of the new gallery, facing west

An Egyptian, unless prevented by untimely death or other force majeure, collected his own funerary equipment, trusting little to the piety of surviving relatives. It would be pleasant to imagine him supervising the construction and adornment of his coffin, anxious to secure a good likeness on figurine and mummy mask, and carefully selecting the sacred formulae that were to secure benefits, material rather than spiritual, after his death. The truth is, however, that very many of the objects formed part of the regular stock-in-trade of the undertakers, a blank space being left in inscriptions for a few personal details to be filled in at the time of purchase. Such insertions can often be detected by differences in the character of the writing, and among the inscribed figurines are two on which the blank spaces were never filled in at all. At one period, when education was at a very low ebb, some undertakers apparently did not know how to fill in the various names, and therefore scrawled roughly on the coffins garbled prayers in honor of “so-and-so”; our example of this strange custom has been already mentioned.

From the elaborate care lavished on the dead, animals were by no means excluded, if they were held sacred-as most kinds were-to some god. Of these humbler mummies some good specimens are on view (Pl. V, above at right): falcons, sacred to the solar Horus; ibises, the birds of Thoth; cats, venerated for the sake of the northern goddess Bastet; and crocodiles, types of Sobk. It is a curious feature of the embalmed animals that their bandaging is much more intricate and decorative than that of human mummies; the reason for this is probably that the very narrow bandages used lent themselves readily to arrangement in designs. Mummies of animals were often buried in coffins of “cartonnage,” molded to represent the animals they contained; two, of a cat and a falcon, are shown in the new Mummy Room.

B.G.