THE Egyptian collections of the Museum include a number of fragmentary Greek Vases found in Egypt. One of these, a tall cylindrical jar, has recently been mended and is now on exhibition in the Sharpe Gallery.

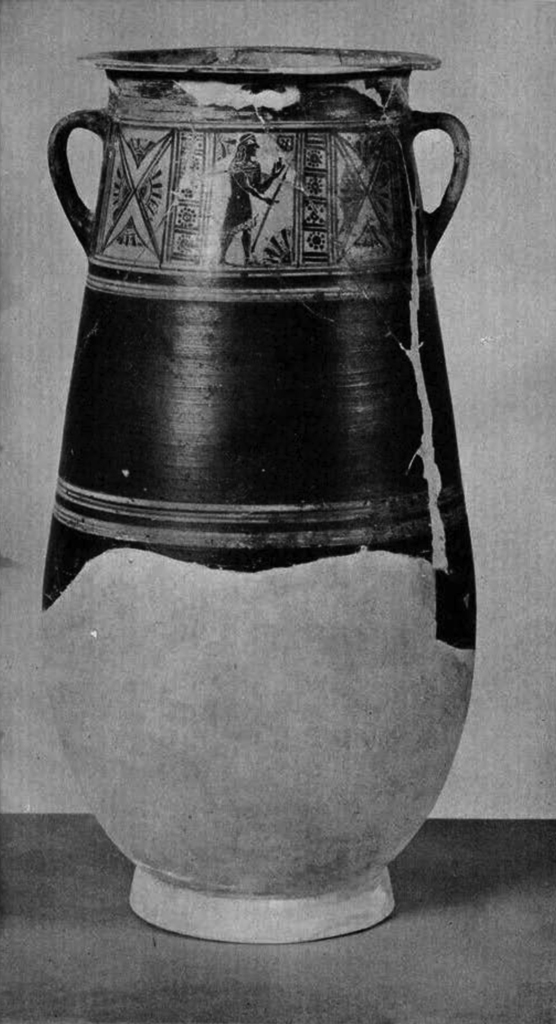

IN April, 1918, while commencing excavations on the site of the Palace of Merenptah at Memphis, Dr. Clarence Fisher found in the surface debris of the site the fragments of the vase shown in Plate V. It is an excellent example of the class of vases generally known as Daphnae Situlae; the name is not a happy one, for in the first place, this type of vase is not, strictly speaking, a situla or pail, and in the second place, it is not proven beyond a doubt that Tell Defenneh, where most of them have been found, is to be identified with the Daphnae mentioned by Herodotus. And yet the name persists.

Museum Object Number: 29-71-189

Image Number: 31497

The vase shows just the blend of Greek and Egyptian stylistic traits which might be expected from Greek potters living in Egypt. The shape is not Greek, although the handles fashioned from three ropes of clay might well be Greek, and the horizontal lip is more Greek than Egyptian. The technique and syntax of the painting, on the other hand, are clearly Greek; thus the lower part of the vessel is colored solidly black, except for reserved stripes, and the main decoration is applied to the shoulder where in reserved panels, framed with decorative motives, are figures in black silhouette. Greek, too, is the habit of using red and black alternately in painting the petals of floral motives, and the use of incised lines for details. The figure of a man in the obverse picture (detail Plate V), has an Egyptian look due, perhaps, in some measure, to the slanting line used for the lower margin of the garment, and the manner in which the spear is carried. The bulls in the reverse picture (detail Plate V), are heraldically placed after the manner of Ionian art. The decorative patterns which surround the pictures are of interest; the dot rosettes are a hangover from the seventh century B. C., but the geometric patterns set in squares which frame the picture of the man, foretell the patterns of later Greek vases.

The question arises how a Greek vase got to Memphis. The answer is perhaps found in a passage of Herodotus, which runs as follows: “The Ionians and Carians who had helped him to conquer were given by Psammeticus places to dwell in called The Camps, opposite to each other on either side of the Nile; and besides this he paid them all that he had promised. Moreover, he put Egyptian boys in their hands to be taught the Greek tongue; these, learning Greek, were the ancestors of the Egyptian interpreters. The Ionians and Carians dwelt a long time in these places, which are near the sea, on the arm of the Nile called the Pelusian, a little way below the town of Bubastis. Long afterwards, king Amasis removed them thence, and settled them at Memphis, to be his guard against the Egyptians.”

Museum Object Number: 29-71-189

Image Number: 31499, 31501

The picture thus becomes clear: Ionian and Carian mercenaries living at more than one site in the delta developed the style of vase-painting shown on the Daphnae situlae. When the garrison of one of these sites, The Camps, was transferred to Memphis by Amasis, Greek potters who worked in this style or, perhaps, our vase itself, came with them.

As to the exact period in the long reign of Amasis when this happened, Herodotus is silent. The date of our vase must thus be determined by criterions of style, and on this basis it may certainly be assigned to the sixth century, and most probably to the first half of the century between the years 600 and 550 B. C.

E. H. D.