“IT is an old affair of the Han Dynasty. When the rulers are married they bestow po shan lu or hill-censers,” so wrote the author of the K’ao Ku T’u in a rather patronizing manner at the end of the eleventh century. Such interesting vessels, however, are worthy of more attention than Lü Ta-lin was willing to grant. Like most “old affairs” there is a wealth of interest latent in their form and ornamentation, their place in the ritual ceremonies of the period, and their artistic qualities.

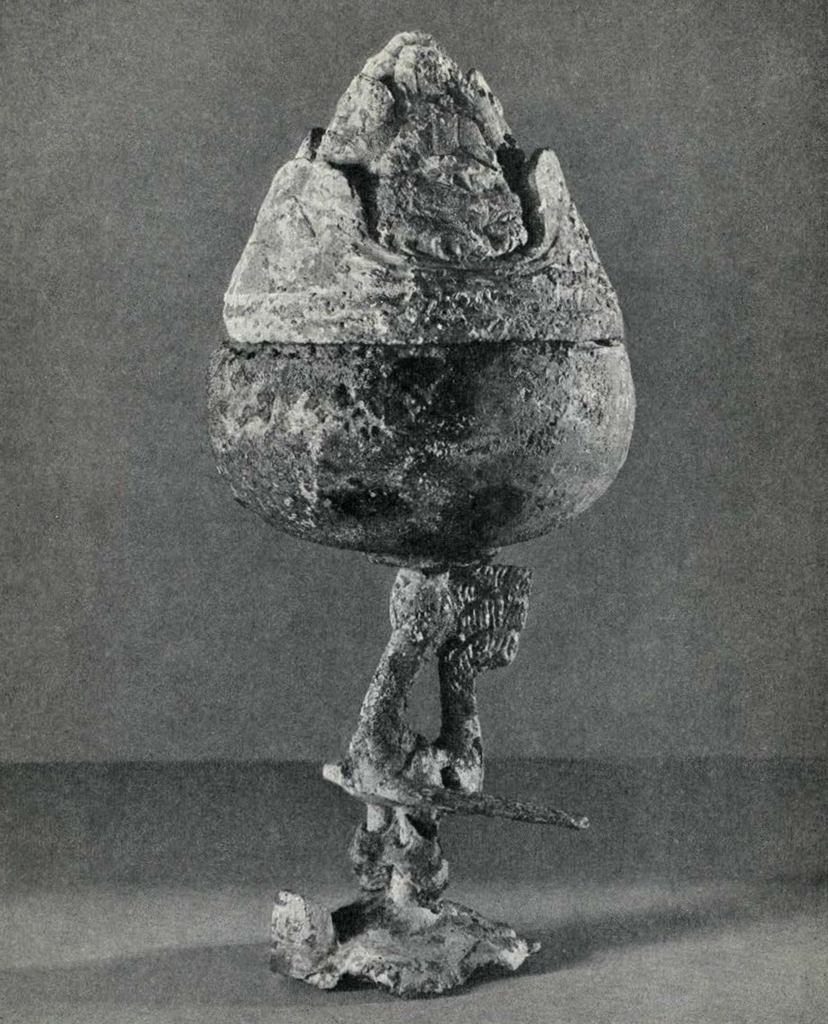

Thus it is that the unusual form of hill censer shown in PLATE X and lately exhibited through the courtesy of Mr. Leon F. S. Stork deserves at least a few descriptive paragraphs. Its rich patina in jade green and soft blue attests its antiquity: and though the corrosion of burial has weakened its body in several places, what it has lost in substance it has gained in beauty, from the adventitious but charming combination of hues it now displays.

Museum Object Numbers: 39-27-1A / 39-27-1B

The base is a tortoise upon whose back stands a phoenix with apparently a snake twisted between its legs. Time has robbed the phoenix of one wing, but originally both were outstretched to give it balance, while poising the hemispherical coupe on the point of its beak, its proudly borne tail assisting in this difficult feat. The conical cover, whence comes the name these censers bear, is in the form of a many folded mountain among whose miniature but beetling crags are holes ingeniously placed so that the fumes from fragrant species of orchids could issue forth. On the surface of the hills are trees and streams and small figures of beasts in low relief. All about the base of the mountain are little waves lapping at the rocks.

This hill motif is particularly characteristic of the Han dynasty during which period it was first introduced and attained great popularity. The Han decorators were great innovators, abandoning the heavy, complex and intricate modes of the earlier bronze designers and introducing lighter, simpler styles. Bronze and pottery censers. with these conical hill-covers are of frequent occurrence; some in jade are recorded in the older books, and a considerable number of green glazed jars are known with similar but unpierced covers.

The origin of the hill motif has been clearly explained by Dr. Laufer. It is derived from the folk legend-a legend probably considerably antedating the Han Dynasty-which conceived the idea of the existence of Three Isles of the Blast where dwelt the Immortals. This legend was apparently first given imperial recognition during the reign of the first great Emperor of the Ts’in Dynasty, Shih Huang-ti (221-210 B.C.) builder of the Great Wall and one of China’s greatest administrators. On the Isles, too, was supposed to grow the drug that prevented death, and it is recorded that the Emperor sent thousands of young boys and girls out into the eastern sea to search for the Three Isles and bring back the precious drug. Later the Han Emperor Wu-ti (140-85 B.C.), influenced a good deal by a host of magicians and necromancers who flocked his court, got excited about the existence of the Isles and sent expeditions there and even went himself to the seaside hoping to be able to see the peaks of the fabulous islands in the dim distance. Since his magicians could conjure up no actual islands on the sea’s horizon, the Emperor went sadly home and contented himself with building a huge artificial lake with three little islands in it, “imitating what there is in the ocean-sacred mountains, tortoise, fish and white birds and quadrupeds and palaces and gates of gold and silver”.

With all this imperial enthusiasm for the folk-legend during this epoch, it is plain that the ideas about the Blessed Islands must have been widely current, and doubtless artisans eager to curry favor at Court adopted it. There is a great deal which one could write about hill censers and the various uses to which many were put, but the late Dr. Laufer so adequately covered this subject it is easy to refer the interested reader to his work for further information.

This particular hill censer is unique, not for its cover, but for the phoenix, and for the snake and tortoise of the pedestal. These animals are familiar in Chinese art from the Chou onward, but no hill censer so supported has as yet been recorded. Indeed those borne otherwise than on a single slightly decorated column are out of the ordinary. In the London Exhibition last year Mrs. Christian R. Holmes of New York lent a delightful specimen where the bowl is held by a little boy sitting on a dragon, and a few are known with rampant affronted beasts on either side of the staff.

H. H. F. J.