BY the generous gift of Dr. Samuel W. Fernberger, the University Museum has received a collection of interesting objects, formerly the prized possession of the late Penobscot Chief Gabriel Paul of Old Town, Maine. Here are represented not only old and rare capes of ceremony but the tools of common Indian crafts.

The Penobscot Indians, one of the five tribes of Northeastern Algonkians, have come to be known as the Wabanaki- “East-Land or Dawn People”- have occupied from very early times the forest, lake and river region of Maine from the St. Lawrence to the sea. Into it they came venturing from the north in the dispersion of the wide-flung Algonkian peoples. The character of their homeland kept them a hunting and fishing people, with little agriculture. They still maintain an independent tribal government of two alternating parties with elected Governor, Lieutenant Governor and Representative to the State Legislature, together with various minor officials. Old Town has long been their leading settlement, its importance dating from 1669. Chief Gabriel Paul, who died in 1936, was not only an appreciative collector of native objects but an authority upon the ancient lore of his people.

Museum Object Numbers: 37-23-3 / 37-23-4A / 37-23-4B

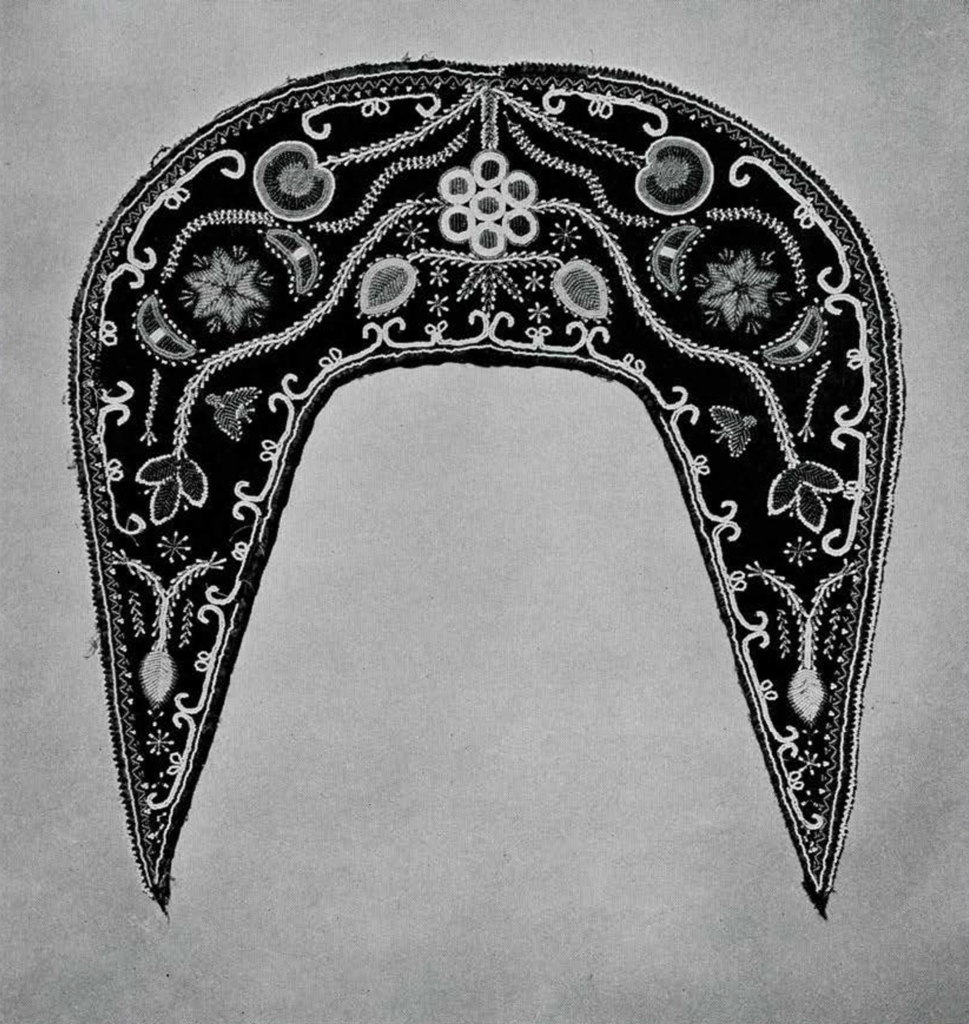

Image Number: 12988

The oldest piece in the collection is a Penobscot cape-collar of black broadcloth, elaborately beaded in floral design, bordered by the characteristic double-curve motif. The arrangement of the large old beads in colors of dark and light blue, deep and light green, yellow, orange, red and garnet produce a pleasing and harmonious effect. Chief Paul believed the cape to date back ninety years. Such capes, together with cuff-like armlets, were worn upon the naked body, and, with a wide kilt of animal pelt, constituted the Penobscot man’s costume of ceremony, doubtless a summer version of the more familiar wide-collared long-skirted ceremonial coat. It is an open question whether this paraphernalia had an independent origin, being added to the ceremonial coat or detached from it. Even cuffs may be aboriginal, since similar wide strips, but made of quilled birchbark, were sometimes worn on the legs. The materials are derived from the European but the artistry harks back to earlier media and techniques. Before the broadcloth, were soft-tanned skins and pliant birchbark, and the forerunners of beading were fine porcupine quilling and moose-bristle embroidery. The purely Algonkian “double-curve” motif, intimately linked with floral design was developed in the latter technique.

A Mohawk ceremonial cape of red silk introduces animal motifs among the floral patterns-a deer on the back, and a beaver in front below each shoulder medallion. The large old beads are dark and pale blue, lavender, dark and light green, deep and pale yellow, red, pink, black, white and transparent. To this cape belongs a pair of cuffs. Orange and flesh are added to the colors in their design and unit beads are set on gold sequins.

Museum Object Number: 37-23-5

Image Number: 13002

The Mohawk, most easterly tribe of the Iroquois League, occupied both banks of the Hudson. Between their land and that of the Penobscot lay three hundred miles of debatable ground often traversed by war parties. In later times of peace a wholesome respect of equals without cordiality was entertained by these former enemies. How the Mohawk paraphernalia came into Chief Paul’s possession, by gift or purchase, is not known. It is old, though not so old as the Penobscot cape.

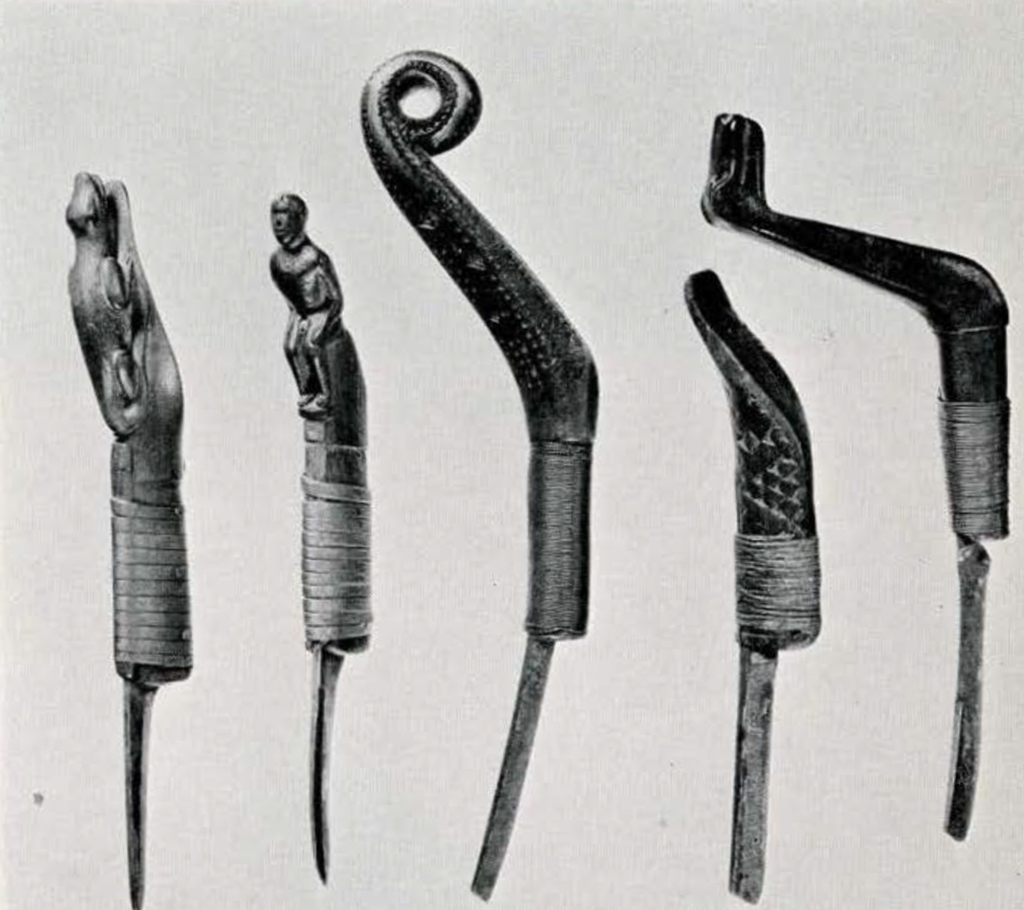

The pride of every good workman is his tools, and Chief Paul had a collection of over a dozen crooked-knives-the tool par excellence for wood carving. To him, each had a history of some previous owner or of his own carving. The figures, human, otter(?), lizard may refer to personal names or be merely decorative as are the cutout and incised designs. The blades are made from steel files ground to a point and a long sharp edge and set in handles carved to fit the closed hand and raised thumb. The knife is held as a dagger is grasped, but with the thumb extended upward to lie along the handle where it gives power to the whittling or carving. They are right or left-handed.

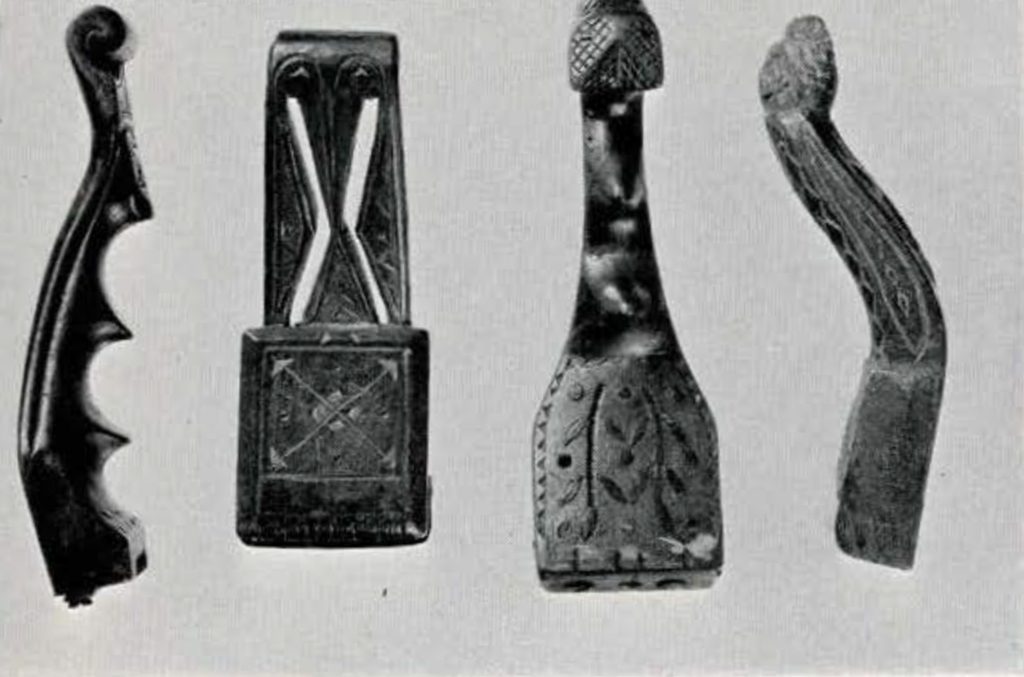

Another group of tools, the splint-strippers or gauges, belongs to the basket-maker’s craft. The material for baskets is black ash, obtained by pounding a cut log until the layers separate; these are pared down into strips. Finer splitting is accomplished by means of the flint-stripper, an Indian invention. Into the carved handles, bits of watch-spring have been set at regular intervals, that with each stroke these teeth cut a number of strips of even size. The basket weaver keeps in her work-basket a set of about a dozen, their gauges ranging from 1/16 to 5/16 of an inch. The handles are beautifully carved and stained to resemble inlay. Notable is the notched finger-hold on some pieces.

Museum Object Number: 37-23-24 / 37-23-18 / 37-23-19 / 37-23-22

Image Number: 13006

Hide scrapers made from the long bones of the moose (?) speak of the ancient art of skin-dressing, and a stone paint-cup suggests the old Penobscot way of decoration, by painted designs sized on with fish roe.

Rarest of all is a wooden mallet specially formed, flattened on one face and one side, used in the making of birchbark canoes. With it the ribs were driven into place, and the canoe lining of cedar strips adjusted.

Dr. Fernberger’s gift, which touches Penobscot life at all angles, save only food-getting-ceremony, foreign contact, travel, clothing, industry – is a valuable addition to the Museum’s series of objects representative of Woodland Indian arts.

H. N. W.

Museum Object Numbers: 37-23-16 / 37-23-15 / 37-23-13 / 37-23-12 / 37-23-14

Image Number: 13003