THE Museum’s great collection of Chinese antiquities, especially in the field of Buddhist sculpture has been increased and strengthened in an unusually satisfactory manner by a gift from A. Felix du Pont of a sixth century bronze Trinity of extraordinary loveliness and importance. The group will ever be rated, indeed, as one of the outstanding treasures of Chinese Art in any American collection and is entirely comparable in quality to the somewhat more elaborate Tuan Fang altar in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and of equal importance to the two sumptuous gilt-bronze altars recently acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art from the collections of Mr. and Mrs. John D, Rockefeller, Jr.

Museum Object Number: 38-32-1A

Image Number: 1237

The group will undoubtedly have immediate appeal even to those who have no close familiarity with Chinese Art, and the photographs of the individual figures and details of them here reproduced will, it is hoped, encourage those who have not as yet seen the du Pont altar to come and see it as it is now exhibited in Harrison Hall. It was executed during the short but infinitely productive epoch of Buddhist Art in China when the simple spiritual quality of the primitive period still guided the sculptors’ hands, and yet the figures, especially the two flanking ones, hint at the gorgeous elaboration that was to supplant the earlier simplicity with the establishment of the T’ang Dynasty.

The figures bear no inscription from which an exact date may be derived: this may have been engraved on the halos which, from the spurs on the back of their heads, we know the figures once possessed. In so many ways, however, do they resemble the figures of the Tuan Fang altar which is dated 592 A. D. that one has no hesitation in saying that the du Pont group was executed in the last quarter of the sixth century. Comparing them with stone sculpture of this epoch-with due allowances for the differing media-confirms this dating.

Museum Object Number: 38-32-1A

Image Number: 1239

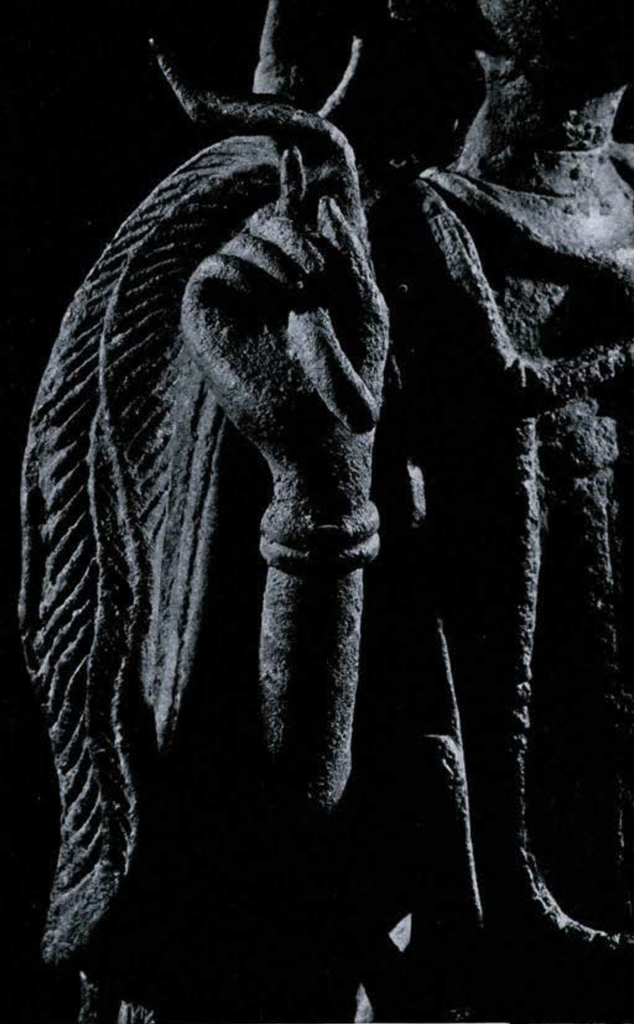

The main figure is that of the Buddha O-mi-t’o fo (Sanskrit: Amitabha) garbed in the monastic simplicity customary in early representations of the buddhas. He is flanked by what we can only successfully interpret as two manifestations of the bodhisattva Kwan Yin (Sanskrit: Avalokites-vara). It would have been more usual to have found one of the attendant bodhisattva to be Kwan Yin, the other Ta Shih-chih (Sanskrit: Mahasthanaprapta) which is the usual composition of an Amitabha Trinity. But inasmuch as the willow branch held by one of the figures and the leaf-shaped object held by the other are attributes solely of Kwan Yin, the supposition that the figures are two manifestations of this deity seems inescapable. Several examples of this and other iconographic aberrations occur in sculptured stones of this era and it need only be borne in mind that the early artists did not feel confined to strict symbolic exactitude nor did the simple devotees of Buddhism trouble themselves with small distinctions between the varied deities of the Buddhist hierarchy, but turned to them with equal piety as spiritual beings holding forth alike the hope of salvation.

The three figures with their attenuated loveliness, with their supernaturally charming countenances and their delicately poised, expressive hands, have, through Mr. du Pont’s timely generosity, become another facet of beauty to the Museum’s great collection of Chinese Art and will long bring delight and satisfaction to those who appreciate masterpieces of great epochs.

H. H. F. J.

North China, Sui Dyansty, about 600 A.D.

Amitabha is the central figure of the three graceful deities that constitute an altar group of unexcelled loveliness, flanked by two manifestations of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. From models executed by master craftsmen, they were cast in bronze during the primitive period of Buddhist Art when spiritual quality combined with artistic perfection to produce the finest religious icons of the Far East. The three figures stand on lotus-petal pedestals supported on delicate niched bases.

Museum Object Numbers: 38-32-3A / 38-32-3B / 38-32-1A / 38-32-1B / 38-32-3A / 38-32-3B

Image Number: 1441

Museum Object Numbers: 38-32-3A / 38-32-3B

Image Number: 1248

Museum Object Number: 38-32-3A

Image Number: 1250

Museum Object Number: 38-32-3A

Image Number: 1254

Museum Object Number: 38-32-2A

Image Number: 1245

Museum Object Number: 38-32-2A

Museum Object Number: 38-32-2A

Image Number: 1247