Museum Object Number: 40-27-7 / 40-27-8

Image Number: 12769

IN the kivas of the Hopi pueblos, the men are busy, for the sun has almost reached the farthest point of his southern journey, whence he will turn northward to his devoted desert land. This month, the New Fire rites, which usher in the Hopi year, will be performed, and then come the Winter Solstice assemblies of all the clans, with a sun-dance and prayers to the germ gods.

Ere long the Kachinas, the “Sitters”, who wait with heads bowed upon drawn up knees, in burial cave or mesa crevice, will rise to seek the time-worn plazas of their erstwhile communal homes. With them will come a host of immortals, nature powers, culture heroes, and animal demi-gods. So, in the ceremonial rooms, the men are mending and repainting costumes and masks, and carving wooden figures of these Kachinas, to be used in the secret rites of the kivas, and given to the children at the time of the Whipping Ceremony, by which children are initiated and adults purified.

Museum Object Numbers: 40-27-3 / 40-27-4

Image Number: 12771

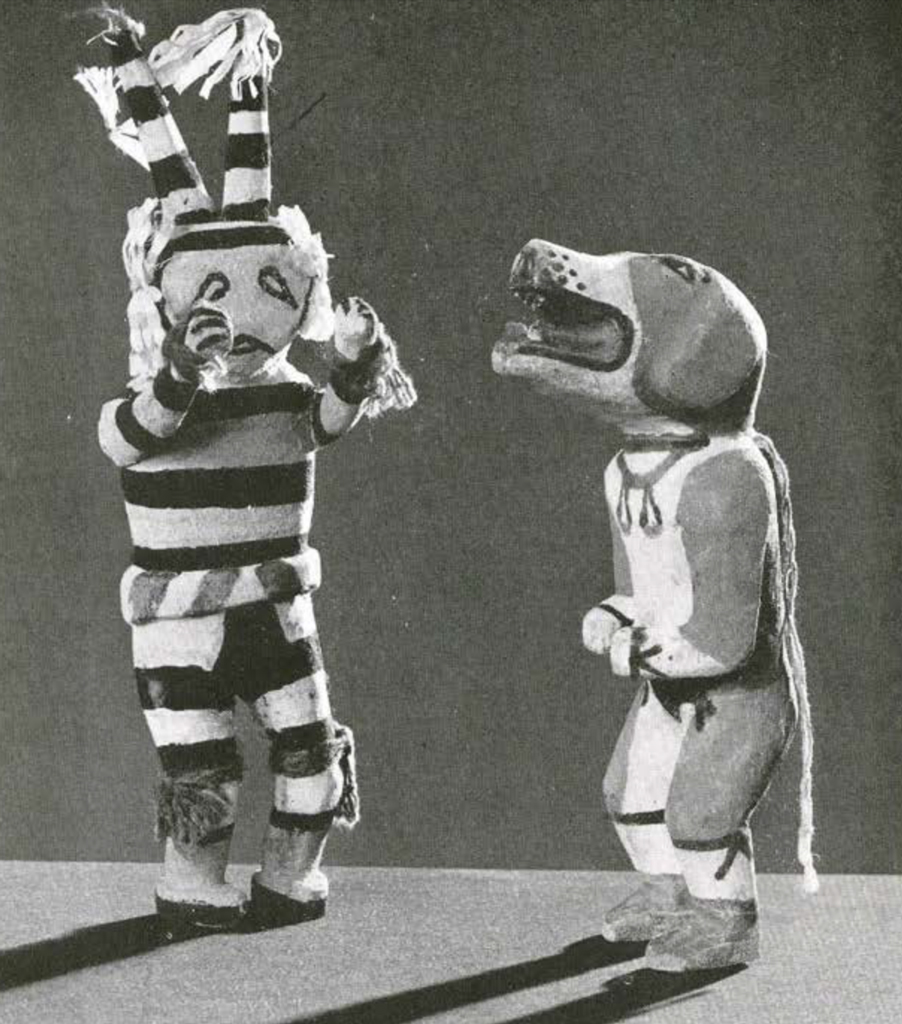

The vanguard of the Kachinas comes in January at the Pamurti, or Return of the Clan Ancients, led by the Sun and Fire Gods up the old trail that leads from Zuni, following a path of sacred meal, and pausing to dance at shrines on the way. Early in February, the advent of the main body is foretold by family parties of Nataka, monsters, red, yellow, black and white, (Pl. VII) who troop from door to door, calling for the dwellers within. In her basket the mother Nataka carries miniature snares, mouse-traps, bows and arrows, which she gives to men and boys, bidding them procure meat. Women and girls each receive a maize ear, with admonition to grind corn against the return of the monsters in eight days. These weird creatures, with huge beastial snouts, ball eyes, horns and crests of eagle feathers (tin in the figure) wear leather cloaks and carry saw, bow and arrows, or war-club in one hand, whip or lasso in the other. Thus armed, prepared to deal with anyone who might refuse the dole, they reappear at the appointed time. Then the fun begins. A lad will offer to contribute a rat or a mole slung from a stick. This is refused with violence. Then a small piece of meat is held out. The Nataka father examines it and shakes his hideous head. When at last a sufficient amount has been produced, it goes into the baskets of the Nataka mother and her daughters, later to feed the hungry horde of personators and celebrants of clan rites in the kivas.

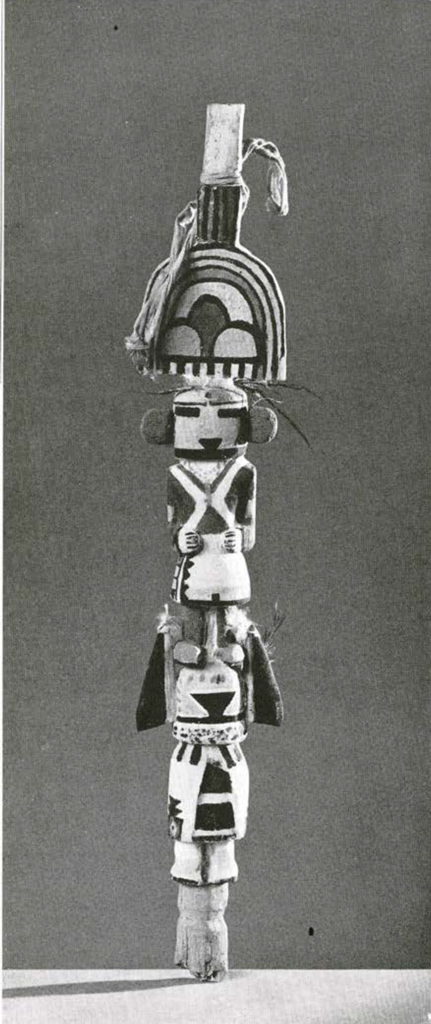

Meanwhile, the Flogging of the Children has been carried out under the direction of Tumas (lower figure of carving, Pl. VII). Her wild-looking sons wield the yucca switches on young and old, and the way is clear for the “return” of the ancients. Carrying masks and robes or kilts, the men slip out of the pueblo to reappear in character, perhaps of Shalako Mana, the divine Corn Maid (Pl. VI) or Sio, the Zuni visitant with the Sky-god attributes. (Pl. VI.)

Museum Object Number: 40-27-6

Image Number: 12770

The Shalako Mana is dressed in typical Pueblo belted woolen gown and cotton shoulder shawl. Her face is painted with the rainbow on her chin and a maize ear across the forehead. She wears the towering tablet of the rain-clouds rising above an arching rainbow. Her name places her among the giant sun-birds, taken over from the Zuni pantheon, her attributes link her to the sky-gods, yet she is the patroness of the maids who grind the maize. In a Hopi mystery drama, two marionette figures of Corn Maidens in a framework of clouds and falling rain, have all the distinctive trails of Shalako Mana.

Sia, the Zuni god, now firmly seated among the Hopi Kachinas, also ranks among the sky-gods. Usually, he wears the Hopi ceremonial kilt with embroidered side; his body painted red and yellow, sun colors, may sometimes show instead the deep blue of the sky (upper figure of carving, Pl. VII). The face of Sia may be simply blue or green, interchangeable colors to the Hopi, barred with black, or it may be painted white with a blue-sky terrace on each cheek; the forehead usually shows twin fields, yellow and red, separated by a black line-the morning and the evening of the same day. (Pl. VII.) Instead of this latter mark, the Sia Kachina figure bears a high sky-terrace with painted tadpoles, a symbol of water.

Museum Object Number: 40-27-2

Image Number: 12772

Not all the Kachinas, who wander through the Hopi pueblos, accosting pedestrians and calling out at kiva entrances to the inmates below, are personages of such high degree, nor are they always the same from year to year. This multitudinous throng results from the composite character of the Hopi people, which has drawn into itself the remnants of many villages, some of distinct origin, each with its own gods and ritual, yet fitting harmoniously into the pattern of Hopi religion.

In this home-coming of the Kachinas, there is also a place for animals, personified by masked men and boys. At the time of the “All Assembly” for the Winter Solstice ceremony, when the returning Sun- or Sky-god, Soyol Kachina, appears as a bird, there is given a bird mask with eagle, hawk, chicken, snipe, owl, duck and hummingbird represented. Later, in the secular clowning which breaks the tension of religious ceremonies, there are various personifications, of chipmunk, squash, bear, dog (Pl. VI).

The supreme clowning, however, is carried on by members of a recognized priesthood, the Paiakyamu, or gluttons. (Pl. VI.) Their bodies are painted with black and white horizontal bands; two horns surmount the head and the ornaments are of white corn-husk. The Gluttons are present at certain functions, as the ceremonial corn grinding. Ostensibly they are buffoons, knowing few inhibitions, yet under the guise of their foolery they exercise certain police duties.

The departure of the Kachinas is celebrated with the elaborate Niman ceremonies at the end of July. A special cylindrical mask, worn at this time, bears in front a tablet showing the high blue terrace of the sky-pueblo. To support it, a stay-stick extends from the back of the head to the top of the terrace. This stay usually has the form of an ear of corn or of the lightning-serpent, but occasionally it is carved with Kachina figures, one mounted upon the head of another. Thus Sio, crowned with the clouds and the rainbow, and wearing a necklace of coral and turquoise beads, stands upon the head of Tumas, mistress of purificatory rites. (Pl. VII.)

The half year ceremonies of masks, of public dance and secret rites, closes with gifts to the children of carved and painted figures-Kachina dolls and the living Kachinas drift out along the trails, to doff their masks and costumes, and unobtrusively return to daily labors.

At such a time, more than a decade ago, the late Dr. John W. Harshberger obtained on the First Mesa, a small collection of the Kachinas, which his daughters, the Misses Harshberger, have graciously presented to the University Museum-a welcome addition to a well-represented series of Pueblo Kachinas.

H. N. W.