Most of us have vague ideas about other peoples, and only rarely are we aware of the complexities underlying the ethnic and cultural make-up of those whose way of life is different from our own. The foregoing brief historical discussion should have made us aware of the fact that there are many groups of Africans, that Negroes are not just Negroes but, on the contrary, are far less alike than the many groups constituting the European ethnic family. Thus we have seen that the Negro population of West Africa, for instance, has undergone developments quite different from those in the central or southern parts of the continent, and that therefore they have ideologies and institutions which are typical of them only. Geographic and climatic conditions influence and determine a great deal of the culture of a people. The Africans of the South African veldt, with an economy based on cattle breeding, are different from the Congolese who grow their guinea-corn in the small clearings of the otherwise dense Congo forests. But even within any area or group of people there are many cultural differences which make generalizations as to their manner and concept of life difficult. Generalizations affecting larger parts of the continent are obviously misleading, if not fallacious. In order to avoid this error, an attempt will be made to characterize a few African cultures which may be regarded as representative in the hope of assisting the visitor to the Museum to visualize the objects of the collection in their proper setting.

Image Number: 721

The Bushmen of South Africa

If technological accomplishments were the only objective criteria with which to measure the cultural achievement of a people, we should readily conclude that the Bushman of the South African Kalahari Desert had the lowest rating. Unfamiliar with animal breeding as well as with agricultural techniques, his livelihood is secured by hunting and the gathering of anything edible that the environment has to offer, such as roots and tubers of the few plants which grow in this desert, and caterpillars, turtles, snakes, and locusts. The whole day between sunrise and sunset is spent in the tedious task of procuring food essential to existence; women and even the smallest children, with only the help of a wooden digging slick, search for what they may find, while the men, armed with bows and poisonous arrows, attempt to run down an antelope, a task which, since game is not very abundant, may keep them trekking for many days. The mere attempt to secure a minimum quantity of water, hardly a problem in other human societies, here becomes a complicated and time-consuming task. Here and there shallow sand pits offer small but regular supplies of water. To these pits women walk for many miles to claim their ration of precious liquid which they collect in ostrich egg shells. There are, however, many areas without such a supply, where it becomes necessary to locate moist soils out of which women literally suck the water drop by drop through reed pipes, and in that way gradually fill their egg-shell containers. Not infrequently even such water sources are at a premium, so that the various succulents such as wild gourds and melons offer the only alternatives for quenching the Bushman’s thirst.

This constant struggle for existence does not leave much time for the niceties and luxuries of life. The shelter of the Bushman is nothing more than a windbreak, a kind of screen made of twigs and bushes behind which the family gathers for the meager meals, and where they sleep comforted only by a fire. Here the few possessions are kept: grinding stones, wooden plates and spoons, and an occasional earthenware vessel secured from the surrounding non-Bushman Negroes. Occasionally the Bushman may find time to prepare a few non-essential ornaments such as bracelets made of strips of skin, of woven grass or intertwined tail hair of the elephant. More common are long necklaces composed of little round disks made from the fragments of ostrich shells (Fig. 3).

The long evenings, so characteristic of the Bushman habitat, are no doubt conducive to the development of a literary art in which these people excel, that is, in the telling of legends and stories with which many volumes have been filled. Occasionally they will take to singing, accompanied by the monotonous sound of the only instrument known to them-the musical bow, which is merely an adaptation of the bow used in hunting. Thus, judging by present-day Bushman standards, it is difficult to believe that their ancestors could have been the artists of the naturalistic rock-art to which we referred earlier. Now the art of the Bushmen is confined to a few geometric designs on their ostrich shells and similar patterns in the painting of their bodies, designs which have nothing in common with those paintings and engravings of animal and human figures which adorn so many South African caves. It seems reasonable that, in the days when the Bushmen occupied other regions rich in game, food, and water, they had the leisure which is a prerequisite to artistic development.

Museum Object Number: 29-12-75

Image Number: 4939

The exacting conditions in which the Bushmen now live have also a direct influence upon their social and political structure. The limited food and water resources prevent large aggregations of people and they are therefore forced to live in small bands with only a few families grouped together in order to pursue communally the quest for food. It is only on rare occasions such as religious festivals that larger groups of kindred families come together to renew the bond of kinship by means of strange rituals and symbolic dances, most of which defy interpretation even by those trained in such matters.

The Pygmies of Central Africa

The small-statured Pygmies, although resembling the Bushmen in some aspects of their culture, live in the less hostile environment of Africa’s virgin forests, where both animal and plant resources are abundant in comparison with those of the Kalahari desert lands. Elephants, buffaloes, and wild boars are numerous and an easy prey of the Pygmy hunter who, equipped with bows and arrows and acquainted with many methods of trapping, can easily secure the meat supply for a minimum existence of his family. With a little effort the Pygmy women collect wild plants, even securing a surplus which may be traded for the agricultural produce of the surrounding Negro tribes and may even be bartered for luxury objects such as metal objects or beads. Some of the Pygmies have abandoned their traditional forest life as hunters and food gatherers and live now with Negro tribes as pottery makers or blacksmiths, or may even be found making a living as musicians or clowns at the courts of the Bahima states of Ruanda or Urundi.

Although their life is very simple, it is more complex than that of the Bushmen. The rich surroundings permit larger groups of people to live together without endangering each other’s food supply, and thus it is not unusual to find settlements of some two hundred or more families. The low huts, in the shape of old-fashioned bee-hives, offer protection against the elements and are equipped with the essentials for living, such as beds of dry leaves, and with pots, plates, mortars, and containers which would suggest a life of abundance and luxury to the average Bushman.

Museum Object Number: 29-12-72

Image Number: 4936

Pygmy life is not a stable one. As the resources are gradually depleted, they move into new localities where game is more abundant, thus shifting their domiciles from time to time. But not only do they move their settlements, but they also change from one political grouping to another. There is no permanent political tie larger than the immediate family unit, and the larger groupings come into existence only when a few families join forces voluntarily, perhaps submitting to the authority of an experienced hunter who enjoys this authority and leadership only so long as he is without competition from a more experienced and successful man.

The Pygmy is himself only in his forest environment. When he leaves it in order to trade with his Negro neighbors he is shy, timid, and generally helpless, not because he is unadjusted to the Negro life, but because of a feeling of inferiority resulting from the fact that the Negro considers himself superior, and believes that the Pygmies are a kind of free game created to be slaves. Most of our information concerning the Pygmies has been gathered from these occasional visitors from the forest, and only few persons have succeeded in following them into their own environment in the dense forests of the Belgian Congo. Those few who, like P. Schebesta, have lived with them for long periods of time, have discovered that Pygmies are not the childlike beings they seem.

The Masai of East Africa

The economic basis of the Masai, the Hamitic intruders of East Africa, is the breeding and keeping of cattle and, to a smaller degree, of other livestock. In their search for suitable grazing lands they migrated with their animals to the semi-arid grasslands which they have occupied since the seventeenth or eighteenth century. To the Masai the tending of cattle is a noble occupation, whereas any other activity, particularly agriculture, is despised as degrading to their tribal pride. It was only as a result of the rinderpest of 1891, which destroyed almost all of the cattle, that a few of the Masai in sheer desperation took to the less active life of agriculturists. The great majority of them, however, preferred the carefree life of cattle thieves, harassing the surrounding peaceful Negro tribes and thus becoming the terror of wide regions both in Tanganyika and in southern Kenya.

Cattle are kept as property; they are not slaughtered for meat but furnish milk and blood, two important items in the nutrition of the Masai. Blood particularly is a desired delicacy which is obtained by inserting a tube in the neck of the living animal. Subsidiary foods. such as meat and vegetables are secured by the Bushmen’s methods of hunting and gathering. Cattle also furnish most of the other essentials of Masai life: Dresses are mode of the hides of fallen animals, strips of hides are worked into ornaments, and even the dung is utilized in the building of their rectangular and flat-roofed huts.

Museum Object Numbers: AF2447 / AF2448 / AF2427 / AF2465 / AF2398A / AF2398B

Image Number: 4954

The social and political structure of the Masai society is subordinated to its economic needs. The migratory tendency of these pastoral peoples does not permit large political groupings, but favors the development of tribal subdivisions which are held together by family ties, although the common origin of all Masai, as well as their common language and cultural ideals, tends to foster a certain degree of solidarity.

The tribal subdivisions are organized in age-grades, with children, unmarried men, married men, and old men forming the four main groups in the tribes, each performing specific functions within the tribal community. The control of political affairs is in the hands of the old men, who have final judicial and executive authority. While the institution of the chief as political leader does not exist, priests, whose offices are frequently inherited, appear to enjoy many privileges which give them a considerable degree of political influence.

The Masai’s pride in their race and their occupation forbade any assimilation of the people whom they conquered, and forced their defeated foes into slavery. Thus we find in Masailand the Wakuafi, who had been deprived of their cattle and were forced into servitude, and the Elgonuno who, as a pariah class, do the work of blacksmiths for the Masai. Even those Masai who lost their cattle and under economic pressure became hunters, as for example the Wandorobo, were no longer recognized as full-fledged Masai and subsequently became slaves.

It is interesting to note that the rigid, militaristic Masai society, in which stealing of cattle, success in warfare, and worshiping of physical accomplishments have been made social virtues, is not conducive to the creation of a distinguished art. There is indeed little worth mention; even many of the utensils used in daily life, such as earthenware containers, wooden plates, or wooden spoons, are not produced by the Masai but obtained from the subject or surrounding tribes.

Museum Object Number: 29-35-1

Image Number: 4941

The Bakuba of Equatorial Africa

The Bakuba, also known as the Bushongo, are typical Negroes. Inhabiting the fertile forest zones in the southern sections of what is today the Belgian Congo, their economy is based on agriculture supplemented by the raising of chickens and goats and by hunting and fishing. Compared with Bushman or Masai economy, Bakuba life is one of abundance. Barring exceptional circumstances, such as long droughts, these people enjoy a regular, ample, and even varied supply of food which, thanks to their tropical environment, is secured with a minimum of effort, permitting leisure for activities other than the quest for food. It is only during the planting and harvest seasons that the women attend to the garden, and the abundance of game and fish makes hunting as well as fishing more of a pastime than a serious and tedious obligation for the men. Teen-age children are physically mature enough to care for the chickens and goats, thus contributing in no small degree to the livelihood of the family. These factors have made it possible for the Bakuba to find time for the production of luxury goods and the “nice things” which have become an important characteristic of Bakuba culture.

The villages have an air of prosperity. Long and wide “Main Streets” are flanked on both sides by palm trees and attractive rectangular huts. Considerable attention is paid to the care and cleanliness of this public domain, where in the evenings or on holidays boys and girls may be seen strolling, dancing, or chatting. Between the huts are open sheds which, like little stores, have been erected here and there along the thoroughfare. These sheds are the shops of the artisans. Here the blacksmith may be seen at all hours of the day engaged in the forging of broad-bladed knives, arrows, and bracelets or other iron ornaments. Just as in any Old-World village smithy, so here groups of children cluster around the craftsman, eagerly awaiting the opportunity to manipulate the hand bellows which fan the lire. Old men squat around the shed and, while smoking their long, curved pipes, discuss local politics in which the smith, here as elsewhere, appears to be well versed.

In other sheds equipped with hand looms, men are seen manufacturing cloth from the fiber of the raffia leaf, while women may be observed embroidering the cloth in colored patterns. The makers of baskets and hunting nets, and above all the wood-carvers, have their working shops on the shaded sidewalks of the village.

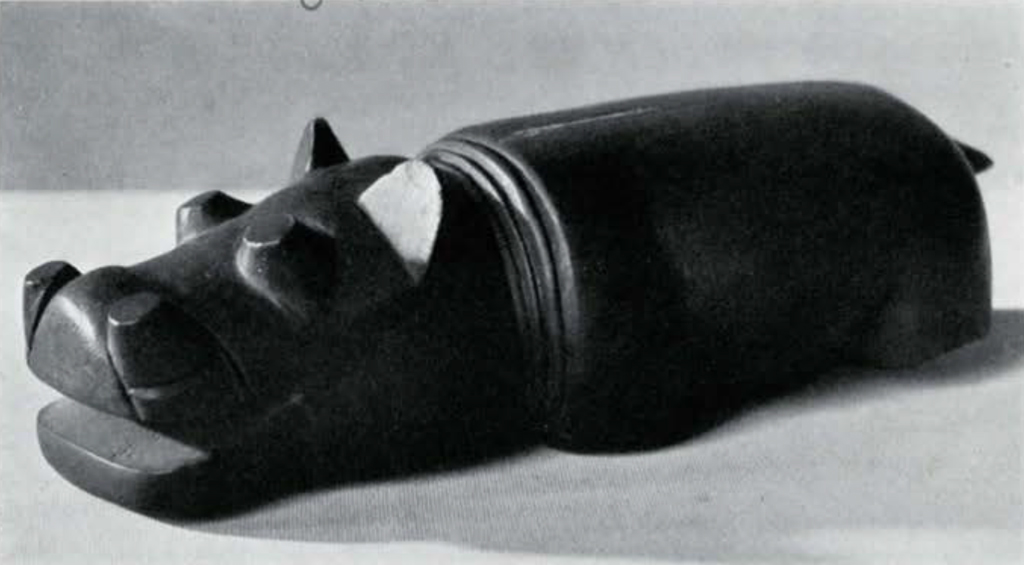

It is this display of industry that gives Bakuba life a special character. The possession of attractive articles has become to them a matter of personal prestige. Even the simplest of the wooden household utensils are decorated with elaborate carvings, the wooden cups (Fig. 6) from which palm wine is drunk, as well as the vanity boxes, are ornamented in tasteful fashion, the long tobacco pipes are often masterpieces of intricate carving, and even strictly utilitarian objects such as the bellows of the blacksmith are objects of art.

Museum Object Number: 30-10-1

Image Number: 4952

Many large villages form the Bakuba nation. A political grouping which embraces 100,000 individuals needs a more centralized authority than do the bands of Bushmen or the clans of the Masai. A king, Nyimi, rules his subjects, delegating a great deal of his authority, however, to individual chiefs, who in turn depend on the advice and support of the village elders. (It should be noted that the authority of chiefs and elders has been curtailed by the present-day authority of the Belgian Government.) The influential position of the king is based upon the wealth he accumulated by declaring a monopoly on ivory, of which Bakubaland had a great abundance as late as 1880. This monopoly was jealously guarded, even to the extent of prohibiting foreigners from entering the kingdom and by offering trade goods for sale only at the borders of the realm.

Bakuba prosperity results not only from the industry of its people, but also from the availability of iron, wood, and ivory, the natural resources for such industries. These favored a development of arts and crafts which reached here a higher level than in many of the surrounding groups of Africans.

The Buganda Kingdom of East Africa1

The kingdom of Buganda, which extends along the northern shore of Lake Victoria and forms a part of present-day Uganda, is one of the few old African kingdoms which have survived to the present. Although the events of the last forty years, resulting chiefly from European control, have deeply affected the traditional life of many Baganda, as the inhabitants of the kingdom are called, Buganda culture and organization have retained most of their pre-European features.

Buganda society is a class structure consisting of the aristocrats, who as feudal lords own large tracts of the land and enjoy other privileges, and of large masses of peasants who work the land. The upper class, who keep themselves aloof from the peasants, claims to be of non-Negro origin, although this claim can no longer be supported by physical evidence. Both upper and lower classes are typical Negroes, in spite of the fact that the former came into the county as alien invaders some thousand years ago.

Museum Object Number: 29-12-69

Image Number: 4932

Buganda’s political organization may be termed a constitutional monarchy; it has a king whose office is hereditary and who is advised by a council of ministers. Both are controlled by a parliament which, as a legislative and judicial body, is composed exclusively of members of the aristocracy. Many members of the Lukiko, as the parliament is called, are also governors of the several provinces and districts into which the kingdom is divided. Although the governmental organization is now well defined, it is far from being static. As in feudal Europe, so in Buganda the feebleness of a monarch was used by the aristocracy to secure political and economic privileges, and conversely an ambitious king would attempt to eliminate the political influence of the aristocracy, establishing himself as dictator.

The king and the aristocracy, as the rulers of the country, form a leisure class engaged only in governmental affairs without direct participation in the country’s production economy. They own the land which, in true feudal fashion, is worked by the peasants in return for tribute paid to the land owner. Fortunately Buganda has a high fertility, producing good crops, particularly of plantains (a variety of banana) which in powdered form constitute the chief item of Baganda diet. Food is so abundant and so easily grown that the demands of the upper class are met without endangering the welfare or even reducing the living standards of the peasant population, which, as has frequently been stated, is better fed than any other African group. It is perhaps for this reason that the Baganda have been regarded as more intelligent and advanced than other peoples of East Africa. The cleanliness of their houses and clothing, the sanitary conditions, and elaborate personal hygiene, reflect clearly their refined standard of living. Their courtesy among themselves and their decorum to strangers are proverbial.

The fertility of the land has attracted great numbers of people, so that the kingdom with its million inhabitants has one of the densest populations in Africa, living in villages and settlements of considerable size. Density of population combined with the existence of a surplus economy has been peculiarly favorable to the development of domestic arts. The aristocracy depends for its leisurely existence on professional craftsmen who build their houses, produce their furniture, such as beds and stools, and supply utensils of all kinds (oil lamps, cups, and containers). The peasants have become dependent on those professionals who specialize in the making of baskets, earthenware vessels, iron tools, and implements. Not only the production of these objects, but also their marketing in the village square or at roadside workshops, has become an essential feature of Baganda life.

Museum Object Number: 29-12-68

Image Number: 4933

It does not surprise us to find in a society of this kind many individuals performing the ceremonial functions which center around the court of the king. Besides the high political officers who would command the title of minister in our terminology, there are officials such as those nominally in charge of the drums which are signs of the king’s office, or others who are the titular heads of the cooks, the brewers, and the bark-cloth makers. Many hundreds of such officials depend on the king for favors bestowed in the form of land.

The social stratification is based on property and wealth which finds its most tangible expression in the size of the land holdings and the number of peasants working in them. In addition, it is customary for the well-to-do families to possess large herds of cattle, not for the utilitarian aspects of cattle breeding, but, like horse breeders in our society, for reasons of sport or to exhibit their wealth. The cattle herds of the Baganda aristocrats may be regarded as their capital assets which they have attempted to increase as much as possible without ever using. Cattle breeding is carried on solely as a means of guaranteeing and enhancing social prestige.

The Agni of the Ivory Coast

In no region of Africa has the artistic genius of the African expressed itself more fully than among the Agni tribes, known as the Boule, Atutu, and Guro, who inhabit the fertile forest zone of the French-controlled Ivory Coast. In recent years the wood carvings of these tribes have become so famous that no respectable museum or collector of African art could afford to omit them from his collections. The University Museum is indeed fortunate in possessing one of the best collections of the Ivory Coast region, a collection which came to Philadelphia long before Ivory Coast art became fashionable.

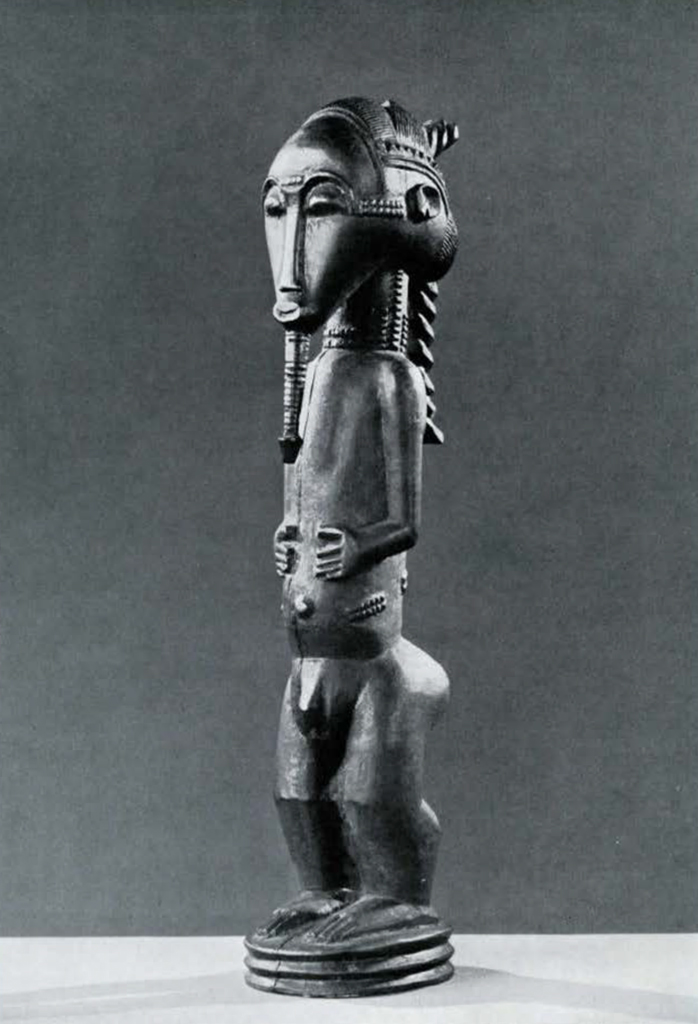

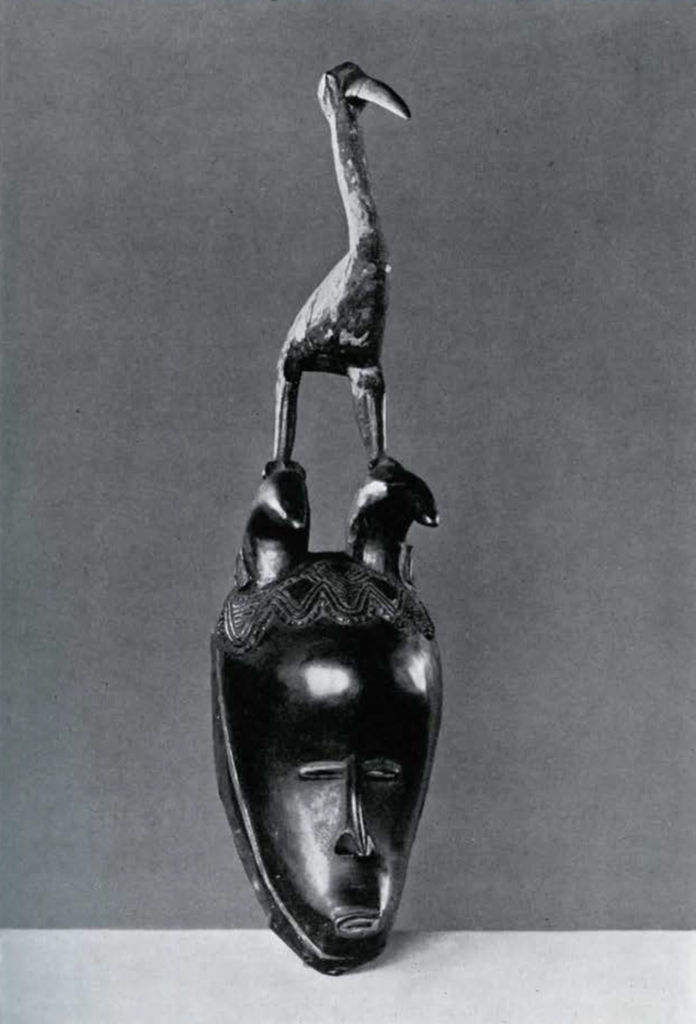

The cultural setting of the Agni tribes is, no doubt, conducive to the development of an elaborate art. Nature fully provides the essential products for an abundant life as it is traditionally conceived by them. Here an upper class, which enjoys many political privileges, regards the support of artists as one of its tasks, and the elaborate religious ceremonies in which many different types of masks (Fig. 14) and figurines are employed, contribute greatly to the stimulation of artistic development. Although the interrelation between religion and art is here as elsewhere in Africa very intimate, the predominant character of Agni art is nevertheless profane. The poor as well as the rich appear to have a great desire for beautiful objects. While men in elevated social positions will accumulate art objects to exhibit their social rank, the less fortunately situated Agni, if he cannot afford the luxury of more pretentious objects, will at least secure nicely decorated utensils for his daily work.

Museum Object Number: AF2002

Image Number: 4949

Thus the plates and spoons which are used for meals are often little works of art, and many of the strictly utilitarian weaving pulleys, profusely decorated, adorn many a collection of art connoisseurs (Fig. 11). We might wonder why the Agni go to all the expense and trouble of carving these rolls, particularly since we do not regard machines as the proper background for artistic expression, but when the question is put to an Agni he has only one answer, which is typical of his general orientation: “One likes to look at nice things, even while working.” A similar attitude is manifested by a wealthy man who keeps figurines of different types carefully wrapped in the interior of his hut, but during his leisure brings them out in front of his house and places them attractively arranged upon a blanket. For hours he may be seen looking at his possessions, obviously enjoying them, and at the same time enjoying the pleasing comments of his neighbors who may gather round.

Such an atmosphere of art appreciation is naturally favorable to the development of art for art’s sake. Several Agni tribes, notably the Atutu, have indeed arrived at a level in which the wood carver will produce an object never intended to perform a useful function but clearly designed for beauty alone. Thus the handle of a sword is shaped without making provision for the insertion of the blade, and to make clear the intention of its non-utilitarian character, the space normally left for the insertion of the blade is covered with various designs. The object will be placed in the collection of one who has the means to own it. The purposelessness of this art may be understood if we explain it in terms of our own concepts, by pointing for instance to a beautifully decorated handle of a hammer, produced by an outstanding artist with the intention of having it placed on the grand piano of our living room.

The craftsmen in Agni society ore professionalized. While weavers and dyers, potters and basketmakers produce normally in advance of their immediate needs and offer their products for sale in market places, blacksmiths and wood carvers work on order for the customers who come to their shops. Although almost every village will have a wood carver or blacksmith, individual craftsmen often enjoy a reputation which brings them buyers from distant places. A craftsman with a good reputation is also a much-desired teacher for young apprentices and, since the latter not only work for the master but must pay him a fee in addition, they help considerably in enlarging the craftsman’s enterprise.

One of the chief tasks of the wood carver consists of the production of human figures for many different purposes. When a person dies the family may desire to have a picture of him placed in the hut to provide a body for the soul of the deceased (Figs. 16 and 17). Or a well-to-do person may want to give a friend his portrait as we present friends with our photographs. In such cases likenesses are sought which the artist may achieve either by cutting and carving from memory or by asking the person to come for a sitting. It is obvious that the likeness achieved does not measure up to photographic standards, but Agni requirements are less exacting. In any case, the Agni recognize the identity of statuettes of friends and relatives.

Museum Object Number: AF5371

Image Number: 4994

The Yoruba of Nigeria

Today we are inclined to think of large-scale political management as a characteristic of higher civilization which is lacking in the societies of Africa. This view is widely held in spite of the fact that in pre-European Africa many peoples formed states which in size and population were considerably larger than many European countries and had or continue to have governmental organizations which demonstrated the ability of Africans to master the complicated art of government. A good example among several such societies is the Yoruba of Western Nigeria, a people numbering about four million. The Yoruba state consists of a confederacy composed of many politically autonomous republics. The head of the state is the Alafin, who has his seat in the town of Oyo. Although his authority once extended over the whole of Yorubaland and adjacent areas, in recent years his influence has considerably declined as a result of European encroachment and civil wars between the autonomous Yoruba states. Nevertheless, the Alafin’s prestige among the average Yoruba is still great, in spite of the fact that his original governmental functions remain curtailed. Many states still pay their nominal respects and tribute to this ruler of the town of Oyo.

The autonomous states are ruled and governed by the Bale, of which in the days of the Alafin’s glory there were more than a thousand. The Bale are members of noble families who do not enjoy unrestricted rule but are closely controlled by a council of elders, frequently referred to as the Ogboni, composed of the influential men and women of the town. Although many of its functions are veiled in secrecy, the Ogboni acts as a senate. Its members elect the Bale from the noble families and may even remove them from office; they fill their own vacancies, although not without an eye on popular sentiment. There appears to exist a keen political interplay between the Bale and the Ogboni. Since the members of the latter are frequently inclined to pursue policies favoring their own interest, a Bale may bring issues before his subjects in the hope of receiving their support.

The centers of the Yoruba states are the towns, of which there are many of considerable size. Abeokuta, Ibadan, and Ilorin, the three largest towns of the Yoruba, are also the largest in West Africa, each having more than sixty thousand inhabitants. The affairs of the town are in the hands of elected civil officers such as the Bale’s “right-hand man” and “left-hand man,” both high administrative officials, and the Jagun or chief of police with a well-organized force.

Each town has its market square which extends in front of the Bale’s house and to which the inhabitants of the town and the surrounding country come for morning or evening marketing. As in most South American towns, so here the market square is the general rendezvous of the town on every national or municipal occasion. It is planted with shade trees for the benefit of the sellers during the day and for loungers in the evening. It is in the market square that shrines and temples have been erected in which the different Yoruba deities are worshiped as were those of the ancient Romans or Greeks.

Image Number: 4996

Like the European towns of the Middle Ages, Yoruba towns are walled and, where there is danger of sudden attacks or long sieges, a town may have a second or outer wall enclosing a large area which can be used for farming during the siege. Massive gates protect the walls and in them the gatemen live, watching not only against attacks but collecting toll from passers-by. Those who bring produce to the market pay a fixed toll, and in return the town officials not only secure peace and order in the markets, but supervise produce and prices against excesses. Special officials are even appointed to keep the highways to the towns in excellent repair so as to invite traders.

The country’s economic life is based on the cultivation of food crops and cotton, both for home consumption and for export to adjacent territories with which the Yoruba maintain an active trade. It is for this trade that the Yoruba have become well known far beyond the confines of their ethnic frontier. Trade is based largely on barter, although in smaller transactions cowry shells are used as a medium of exchange. We are inclined to smile at so simple and so “useless” a form of money, yet there is no basic difference between the cowry-shell currency and our own based on gold or silver. Cowry shells, like gold, have a luxury value and are sought after and utilized in ornamenting apparel or in making other decorations. The value of cowry money is not stable but varies according to its availability. In the neighborhood of the seashore where the shells are available in quantity, its purchasing power is low, increasing in value, however, the farther one moves inland and away from the source of supply. In contrast to our own money, cowry has retained its original commodity value. It would be wrong to assume that a Yoruba could make an easy living by merely going to the seashore and by picking up “money.” The commodity value of the cowry regulates itself in such a way that the person who grows yams and sells them for cowry will produce about the same value as the person who collects cowry and buys yams for it.

In order to facilitate the counting of large sums, cowries are strung together, usually in five strings of forty each, or two hundred in all, which represent a value of about three English pence. Since European coins have been introduced, cowry is used only in the purchase of fruits, herbs, or small quantities of food whose market price would be less than the British one-penny coin.

As may be expected in such a highly urbanized society as that of the Yoruba, economic life is highly specialized. In small as well as large towns there are weavers, leather workers, tanners, rope makers, blacksmiths, wood carvers, and specialists of other crafts catering to both rich and poor. A wealthy Yoruba is greatly concerned with his appearance and will order his dress-a loose, flowing robe, vest, and wide trousers-from a professional tailor. Hair and beard are attended to by barbers.

Museum Object Number: AF5102

Image Number: 4995

Even their music is not always a spontaneous expression of the peasant folk, but in the towns there are professional musicians who at weddings, funerals, or other occasions will entertain the guests for a consideration. Wealthy Yoruba may hire a drummer or trumpeter as personal attendant. As in other cultures, the arts do not appear to pay too well or too regularly; it is therefore not unusual to see musicians parade the streets asking for alms to be placed on their drums.

Outstanding among the professionals are the doctors, who here are not the notorious witch doctors we hear so much about, but are general practitioners who have considerable knowledge regarding herbs and cures which they normally administer with no more ballyhoo than many of our own quacks. Although Yoruba culture knows no such institutions as hospitals, some of these doctors keep on their premises a number of invalids suffering from such chronic diseases as leprosy, insanity, or chronic ulcers.

The religious life of the Yoruba is also professionalized. The many recognized deities have their own cults which are presided over by various priests graded in an hierarchal system. A long course of serious study is necessary for initiation into the priesthood, the young novices being trained by older priests in their respective denominations. The deities are many. There are Olorun, the Lord of Heaven; Orisala, the shaper of man; Ori, the household deity; Ogun, the god of war; Esu, the author of all evil; and in addition to these major deities there are hundreds of lesser ones. Of the latter, Shango, an ancient Yoruba king, and Oya, his wife, are particularly noteworthy, since they represent deified Yoruba heroes whose cults today enjoy wide popularity. A special status is enjoyed by the priests of the Ifa cult centering around the town of Ife, which in the Yoruba pantheon has the same position as Delphi in ancient Greece, in that it contains the Yoruba oracle. People in need of advice may go to the Ifa priests who, by means of different oracles-and of course for a consideration-will answer questions much after the manner of the oracle at Delphi.

The Benin Kingdom of Nigeria

The Bini, as the inhabitants of the famous kingdom of Benin are called, are closely related to the Yoruba culturally. At one time Benin was under the rule of the Alafin of Oyo, but when the Portuguese visited there toward the end of the fifteenth century it had already become an independent and powerful kingdom. The political life and organization of Benin does not differ fundamentally from that of any other Yoruba city-state, but its art is unique, and for this reason it seems well to give the Bini special space. The University Museum is fortunate in having an excellent collection of their art, which is highly prized by museums and art connoisseurs in general.

Museum Object Number: AF5108

Image Number: 4992

Benin as a political institution has a bad reputation. During the nineteenth century it became the city of horror, because of the wholesale slaughter of human beings. While it is true that the powerful theocracy of priests, reducing the political influence of the king, forbade all trade with Europeans and enforced this command in rigorous fashion, and that at times their religious code demanded human sacrifices so repugnant to European ideals, it is equally true that these atrocities were greatly exaggerated for political reasons. Benin was conquered, and, as a result of punitive expeditions, large sections of the populous and well-planned city were unnecessarily destroyed.

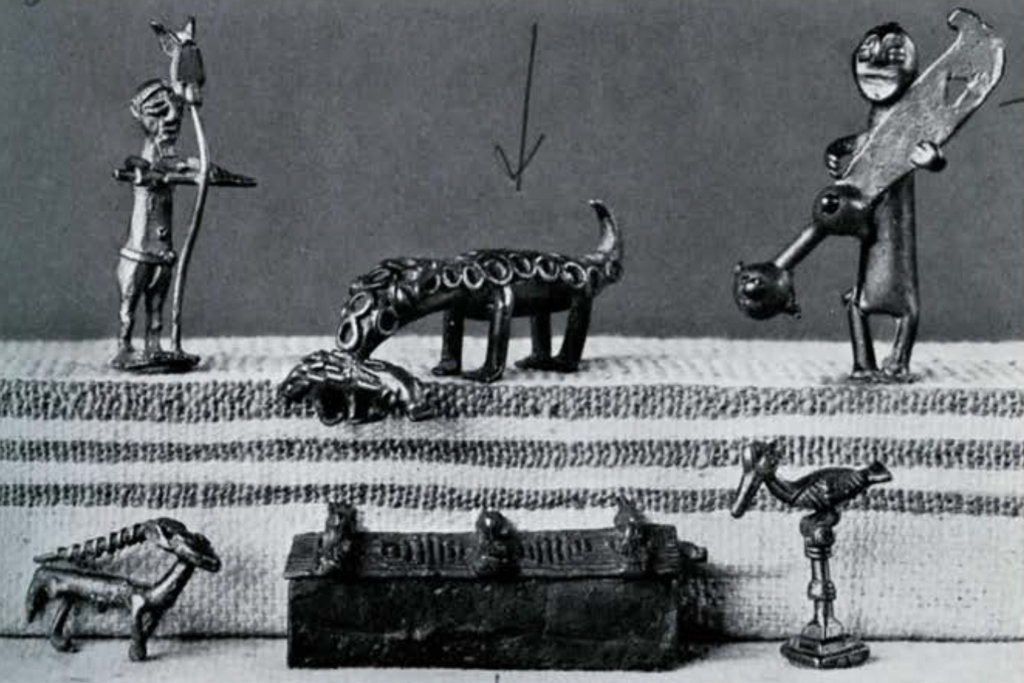

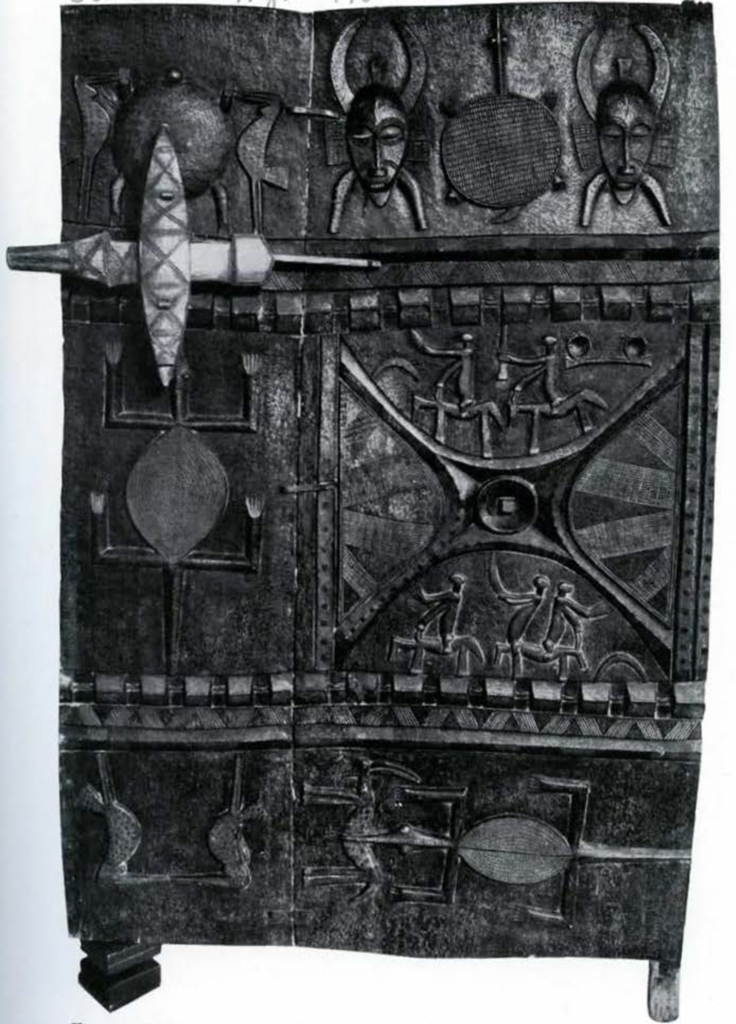

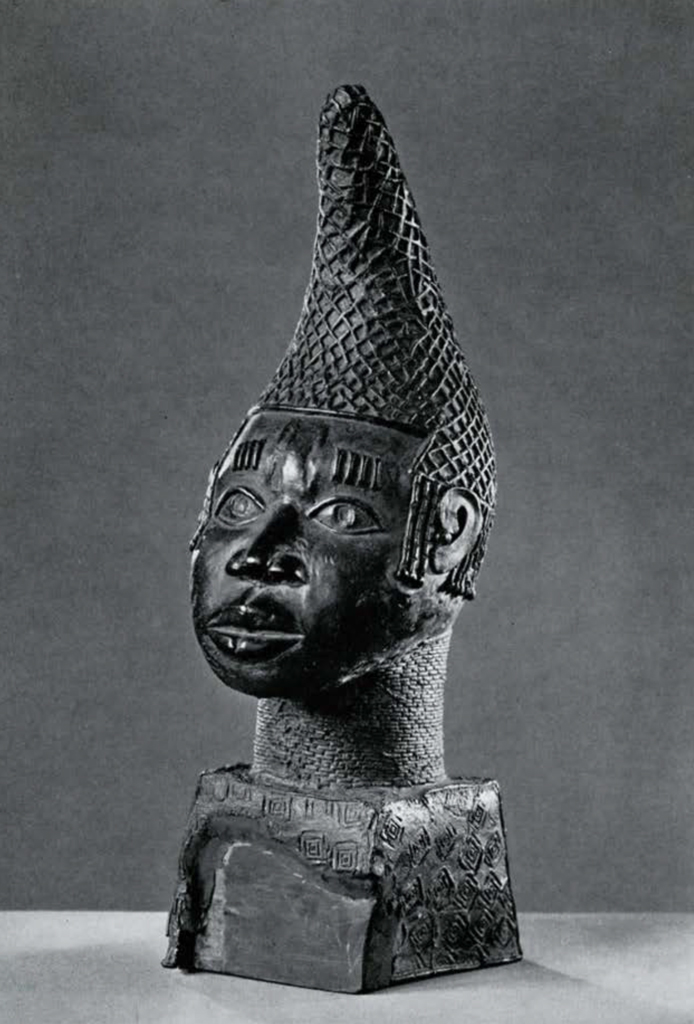

The conquest of Benin in 1897 revealed the existence of little-known African art. The metal, particularly the bronze castings, of the Bini are outstanding examples of African craftsmanship, the origin of which goes back many centuries and according to local tradition was introduced from the town of Ife in Yorubaland, where excavations only recently have unearthed magnificent bronze objects.

Benin bronzes may be divided into three different classes. There are life-size human heads, models of animals and human beings, and reliefs of scenes, animals, human beings, and mythological symbols (Figs. 20-23). The popular belief producing so complex an art as these Benin bronzes has given rise to the theory that Benin art was introduced from the outside, with Egypt, India, and Portugal mentioned as the possible places of origin. While it cannot be denied that early Europeans have indirectly influenced the motifs of this art, the style is distinctly African, and the method used in metal casting-the cire perdue process2-is indigenous to many West African regions, as for instance, the Ashanti and Agni, who produce by this method the miniature brass figures which were used as gold weights (Fig. 13).

Europeans figure prominently on the Benin reliefs. We see Europeans on horseback and in battle with Africans. One relief depicts Europeans slaughtering some Africans who are bound, with their hands clasped as in prayer, while the heads of other Africans are lying on the ground.

Museum Object Number: AF2065A

Image Number: 4993

Benin art is also well known for its ivory carvings, among which large elephant tusks carved in relief are particularly representative. More appealing to the European eye, however, are the goblets, tankards, armlets (Fig. 24), and other ornaments which are decorated either in relief or with openwork which reminds us somewhat of Renaissance styles.

The Bosso of the West Sudan

Although European penetration has somewhat leveled the sharp contrasts existing in the African Sudan, it still remains a country of great ethnic complexities. Many tongues are spoken in this land of large cities and wealthy kingdoms, where the well-dressed aristocrats of the city are to be found in the colorful market places rubbing elbows with the nearly naked peasant tribes. Now the powerful kingdoms of the Sudan have disappeared; they have been absorbed by the administrative districts of French West Africa in a slow process of bloody conquest which took the whole second half of the last century. The culture of the Sudan states and the splendor of its cities are one aspect of Sudan life; the other is the life of the indigenous population, which has continued its traditional life unaffected by the changes which Moslem conquerors brought about in the capitals of the states. The cultural difference between these groups was even greater than that to be found between the New Yorker of Park Avenue and the mountaineer of West Virginia.

Among these indigenous peoples are the Bosso, who live somewhat isolated on the many islands formed by the Niger and Bani rivers. Here they have remained undisturbed by the neighboring kingdoms of Segu, Marko, and Massina, and thus have preserved their culture, which appears to be typical of these regions of Africa prior to the many invasions which caused the establishment of the large states.

The Bosso, like other tribal relics of the Sudan, are agriculturists who supplement their livelihood by fishing and occasionally by the breeding of small animals. They do not form large political groups; the largest unit is the village, which is controlled by a chief or Nagutu, a mayor whose office is hereditary, although his authority is limited, since the final political power rests with the elders of the secret societies.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-5

Image Number: 4999

Secret societies here have little in common with our general notion of such organizations; they are not secret in the sense that their membership or their ritual is secret, as is the case in some other African regions. They are more aptly described as age-grading societies, since every male, with the exception of physical misfits, joins the societies, which consist of three classes graded according to age. Young boys form the lowest grade, young married men comprise the members of the middle grade, and men of forty-five years and over form the upper grade. It is these last who rule and control the tribal affairs.

There are various rituals connected with the initiation into each group which are primarily of a religious nature and differ within the three grades. Masks representing deities and spirits, as well as drums of many shapes and bull-roarers with different tones, have a prominent place in the grades and are carefully kept from the eyes of those not yet initiated.

The societies which control the political and the religious life of the Bosso are not limited to one village or political unit, but are inter-tribal in character in that the same age-grades with the same rituals are found in adjacent villages; and since a certain amount of intercourse exists between the otherwise loosely related groups, the secret societies effect some degree of political coordination.

Bosso culture is not easily comprehended by us because of the deep-rooted mysticism which reveals itself in the many manifestations of what we, for want of a better term, like to call witchcraft, the term frequently used by Europeans to describe most concepts of preliterate peoples which they do not understand. The Bosso, like other Sudan tribes, believe that they are surrounded by a host of werewolf-like creatures, and a major concern of their lives is to combat them with amulets and other magical devices. Thus children are warned by their parents to recite protective charms and to put on amulets before they go to sleep, so that vampires will not suck their blood during the night. Such precautions are numerous, and the Bosso appears to take them quite perfunctorily. He has a relationship to the supernatural which reminds us of our own ancestors in the days when werewolves, witches, and other evil spirits were still supposed to inhabit the earth.

The Troubadour of the Sudan

Africans are famous for their folklore, their legends and fables, a few of which have found their way into world literature by way of Uncle Remus collections of different types. But nowhere else has African literature reached such heights as in the epics of the West Sudan. Here, where the feudal lord once led a life similar to that of the European knight of the Middle Ages and the young nobleman aspired to a life of fame and glory as a warrior, epics came into existence which glorified the accomplishments of the warrior. Professional troubadours who had accompanied the heroes in their search for adventure would praise and recite the deeds of their masters. They would tell how the nobleman defeated the ruler of a town in a duel, how he helped people in distress against their enemies, and perhaps how he fought for the possession of a woman. As these stories were recited from one generation of troubadours to another they were interwoven with legend, thus creating those epics which are now rapidly disappearing.

Here follows, in free and abbreviated translation, an example collected among the Soninke of the Sudan by Leo Frobenius3 in 1912.

Annallya Tu-Bari was the daughter of a prince. She was wise and very beautiful. Many knights came to seek her hand, but Annallya always demanded of each that he submit to an heroic test which he was unwilling to undertake.

Annallya’s father had a quarrel with the prince of a neighboring town, and in the duel which followed he was defeated and lost part of his land. His pride was so hurt that he died. Annallya inherited the father’s town and land and then demanded from every suitor that he not only win back the lost land but also that he conquer eighty other towns and villages as well. Years passed, but no one dared to undertake so warlike an adventure. As time went on and Annallya remained unmarried, she grew more beautiful with every year, and sadder too. The lovelier she grew the more melancholy she became, until she lost all joy in life. It finally was so that she and her subjects forgot how to laugh.

Image Number: 4960

In Faraka there lived a prince called Gana, who had a son named Samba Gana. When the son grew up, he followed the custom of his people and left his home to conquer land of his own. Samba Gana was young, Samba Gana was happy, Samba Gana laughed with joy when he left home. Samba Gana challenged the princes of other towns. They fought. The townsfolk watched. Samba Gana won. The conquered princes asked for their lives and offered their towns. Samba Gana laughed and said, “Keep your towns. Your towns are nothing to me.” Samba Gana fought with one prince after another. He always returned what he had won. He always said, “Keep your towns. Your towns are nothing to me.”

One day Samba Gana was encamped on the Niger. His bard sang of Annallya Tu-Bari; he sang of Annallya Tu-Bari’s beauty, of her melancholy, of her loneliness. The bard sang: “Only he who conquers eighty towns can win Annallya and make her laugh.” Samba Gana listened. Samba Gana sprang to his feet. Samba Gana shouted: “Saddle the horses! We ride to the land of Annallya Tu-Bari.” They rode day and night. They rode day after day. They came to Annallya Tu-Bari’s town. Samba Gana saw Annallya Tu-Bari. He saw that she was beautiful and did not laugh. Samba Gana said, “Annallya Tu-Bari, show me the eighty towns.” Samba Gana made ready. He said to his bard, “Remain with Annallya Tu-Bari, sing to her, make her laugh.” The bard remained in Annallya Tu-Bari’s town. He sang every day of the heroes of Faraka, of the towns of Faraka, of the serpent of the Issa Beer which made the river rise so that one year the people would have a surplus of rice and went hungry the next. Annallya Tu-Bari listened.

Samba Gana traveled through the country. He fought with one prince after another. He conquered all of the eighty princes. He said to every conquered prince: “Go to Annallya Tu-Bari and tell her that your town is hers.” All eighty princes came to Annallya Tu-Bari and remained in her town. Annallya Tu-Bari’s town grew and grew. Annallya Tu-Bari ruled over all the princes of the land surrounding her town.

When Samba Gana returned to Annallya Tu-Bari, he said, “Annallya Tu-Bari, all that you wished for is yours.”

Annallya Tu-Bari said, “You have accomplished the task. Now take me.”

Samba Gana asked, “Why don’t you laugh? I will only marry you when you laugh.”

Annallya Tu-Bari answered, “Before I could not laugh because of the pain caused by my father’s shame. Now I cannot laugh because I am hungry.”

Samba Gana asked, “How can I still your hunger?”

Annallya Tu-Bari said, “Conquer the serpent of the Issa Beer which causes surplus in one year and poverty in the next.”

Samba Gana said, “No one has ever dared such. I will undertake it.” Samba Gana went away.

Samba Gana looked for the serpent of the Issa Beer. He found the serpent. They fought. Sometimes the serpent won, sometimes Samba Gana won. The Niger flowed once on the one side, then on the other. Mountains crumbled, and the earth cracked. For eight years Samba Gana fought with the serpent and after eight years he conquered it. He gave the blood-stained lance to his bard and said, “Go to Annallya Tu-Bari, give her the lance, tell her that the serpent is conquered, and see if Annallya Tu-Bari laughs now.”

The bard went to Annallya Tu-Bari. He told the story of the struggle. Annallya Tu-Bari said, “Go to Samba Gana and tell him to bring the serpent into my land so that as my slave it may lead the river into my country. When Annallya Tu-Bari sees Samba Gana with the serpent, then Annallya Tu-Bari will laugh.”

The bard gave the message to Samba Gana. Samba Gana heard the words of Annallya Tu-Bari. Samba Gana said, “It is too much.” Samba Gana took the bloody sword, plunged it into his breast and died. The bard took the bloody sword, mounted his horse, and rode to Annallya Tu-Bari’s town. He said to Annallya Tu-Bari, “Here is Samba Gana’s sword. It is red with the blood of the serpent and that of Samba Gana. Samba Gana has laughed for the last time.”

Annallya Tu-Bari summoned all of the princes who were gathered in her town. She mounted her horse. The princes mounted their horses. Annallya Tu-Bari and her princes rode toward the east. Annallya Tu-Bari came to Samba Gana’s body. Annallya Tu-Bari said, “This hero was greater than all before him. Build him a tomb to tower over that of all kings and heroes.” The work began. Eight times eight hundred people excavated the shafts, eight times eight hundred people built the chamber, eight times eight hundred people carried earth. The mound rose higher and higher.

Every evening Annallya Tu-Bari and her princes climbed to the top of the mound. Every evening the bard sang the song of Samba Gana. Every morning Annallya Tu-Bari arose and said, “The mound is not high enough. Build on until I can see Wangana.” Eight times eight hundred people carried earth and piled it on the mountain. Eight years long the mountain rose higher and higher. At the end of the eighth year when the sun rose the bard looked around and called, “Annallya Tu-Bari, today I can see Wangana.”

Annallya Tu-Bari looked towards the west. Annallya Tu-Bari said, “I see Wangana. Samba Gana’s tomb is as great as his name deserves.”

Annallya Tu-Bari laughed.

Annallya Tu-Bari laughed and said, “Now leave me. All of you princes spread over the world and become heroes like Samba Gana.” Annallya Tu-Bari laughed once more and died. She was buried beside Samba Gana in the burial chamber of the mound.

This is one of the many stories which reflect an epoch of the Sudan which may be termed the “heroic epoch,” a period which might very well coincide with the various Hamitic invasions to which we referred before. Stories like the one retold above, many of them much longer, are part of special collections known to the troubadours by special names. Thus the Soninke have a dausi, a collection of important hero stories, and a pui, which contains the lesser ones. There is some justification for the theory that the stories of the dausi, now disconnected short stories, once formed a continuous story analogous to Beowulf or the Niebelungen. But since the dausi, or the pui were never written but were transmitted only by word of mouth from one generation of troubadours to another, it will be impossible ever to recover them, and we shall have to content ourselves with the few fragments which remain.

Conclusion

The foregoing examples of cultures have shown the great variations that exist in the continent of Africa. In selecting the few examples thus briefly described, we cannot even claim to have offered an evaluation of all the most typical cultures which have flourished there. For those who may have been stimulated by this Bulletin and desire to obtain more detailed information, the titles of the reading list will provide a guide to authentic accounts.

1 The kingdom of Buganda is located in the territory of Uganda. The inhabitants are called Muganda (sing.) and Baganda (plural). ↪

2 Around a core of hardened sand is molded a wax model which is then coated with clay. When the molten metal is cast into the mold, the wax melts. The resulting rough casting is finished by tooling, punching, etc. ↪

3 L. Frobenius, Atlantis, VI (1921), 72-75. ↪