SOME one has said it takes a heap of living to make a home. This statement suggests that while a house is not necessarily a home there exists an intimate relationship between homes and houses. Therefore, when we read that approximately 3,000,000 families in the United States must attempt to create homes without dwellings of their own in which to house them, we begin to comprehend the magnitude and timeliness of the present housing problem. A brief consideration of the multiple functions which houses fulfill in human society may assist in enlarging our understanding of the significance of the housing crisis.

PROTECTION AGAINST THE ELEMENTS

Dr. Hooton once suggested that any self-respecting ape would be embarrassed by the necessity for acknowledging as relatives animals so devoid of bodily covering as are humans in birthday attire. Due to our tropical ancestry and due to the domestication of the species homo sapiens, mankind has come to be the “nudist” of the anthropoids and one of the animals most in need of protection against unfavorable climatic conditions. However, before expending any sympathy over man’s biological deficiency, we should be sure that it is not a blessing in disguise. Any protection which is inherited, like the fur coats of northern animals (which incidentally females of the human species acquire only at considerable cost), definitely restricts the regions which the animal can comfortably inhabit. Lacking such protection, members of the species homo sapiens have turned adversity to advantage, and by inventing the house secured a means of protection against the elements which has permitted man to attain the distinction of being the most widely distributed species in zoological history.

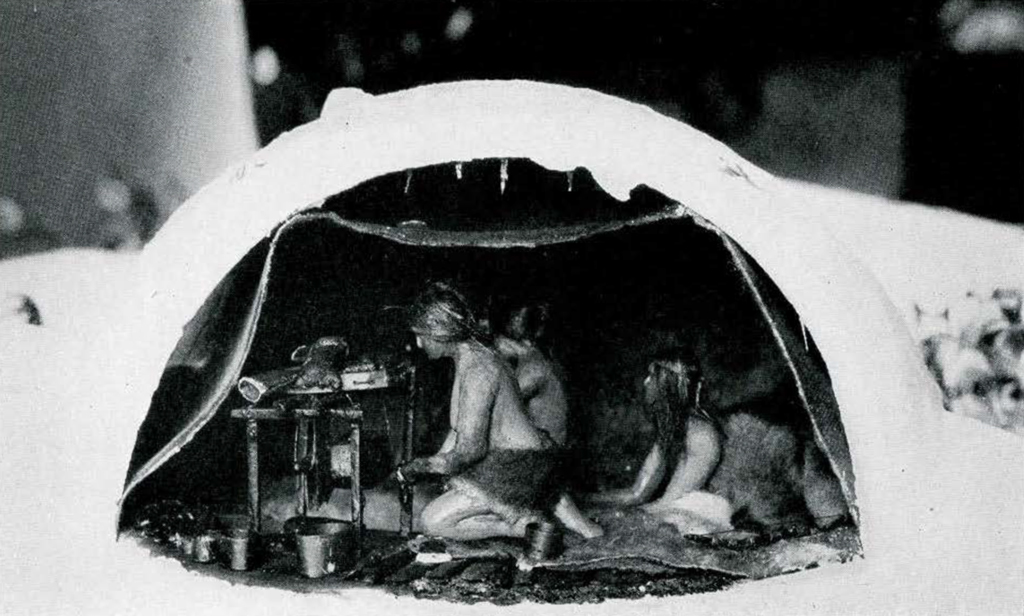

Houses are a superior means of protection against unfavorable climate chiefly because they are amazingly adaptable and can therefore serve to shield from a wide variety of climatic conditions. The Central Eskimo builds an igloo (Plate II) which is admirably effective in insulating its inhabitants from the extreme arctic cold. Tropical dwellers such as some of the Indians of Guiana (Plate III) construct an arbor type house equally effective in shielding the family from the debilitating heat of their environment. Houses are also adaptable from the standpoint of the materials from which they can and have been made. It is virtually impossible to recall any product of field or forest, mine or quarry, land or ocean which has not been in some form utilized in house building; and largely due to this fact, it is also impossible to recall any human group which has failed to include housing as an item in its culture pattern.

Image Number: 12548

THE HUMAN DESIGN FOR LIVING

A house is a structure wherein the activities of the human family are centered and, therefore, it occupies a place in the hominid design for living roughly comparable to the nests of birds and hives of bees. The human family group, however, differs from that of other animals in lacking a uniform composition and in possessing great diversity of function. Variations in both of these factors naturally stimulate great diversity of house types.

The inescapable minimum in family composition is a pair of spouses and their offspring. This group may be altered by changing the ratio of spouses in two ways. The husband may marry more than one wife and establish a polygynous family, or a wife may be shared by more than one husband, thereby creating a polyandrous family. Regardless of which alteration occurs, the society emphasizes in its family system the importance of the conjugal partners, be they two or more. A more radical alteration in family structure occurs in the case of the extended family. In such families, kin are counted unilaterally or, in other words, one is related only to either the mother’s or the father’s kin but not to both. Furthermore, in extended families, it is the larger consanguineous or blood group and not the conjugal pair which is all important to society. Marriage under the extended family system does not mean the creation of a new family. Whether married or single, a person belongs throughout life to the extended family into which he was born. The most significant change accompanying this form of marriage is that of residence. Where members of the extended family count their kin through relationship to the mother, it is generally the practice for husbands to go to live with the wife’s family, whereas, if the relationship stems from the father, wives take up residence in the home of the husband’s people.

Let us now consider the effect of different family types upon housing. Perhaps the most successful scheme for housing the polygynous family in a manner which will alleviate latent jealousies between the several wives is found among numerous tribes of Africa. The house is really a group of buildings known as the compound. Within the walled compound is located a hut for each wife and usually the granary for the family grain supply. In a sense the family consists of one or more “mother families,” for each wife dwells with her children, cooks for them and is almost entirely responsible for their discipline. The father rotates between the huts or homes of his wives, living with each in turn for a month or a week. It is perhaps interesting that sociologists have drawn certain parallels between the mother families of African people and the modern suburban family in the United States. With the father leaving home at an early hour for his place of business and returning for a late dinner in the evening, the importance of the mother in running the house and managing the children has greatly increased. While no fundamental changes in housing design have been attributed to this change in the American family, it has been suggested that the popularity of automatic appliances such as stokers and oil burners has come through the necessity for the wife to assume many of the duties formerly carried out by the husband.

Image Number: 13381

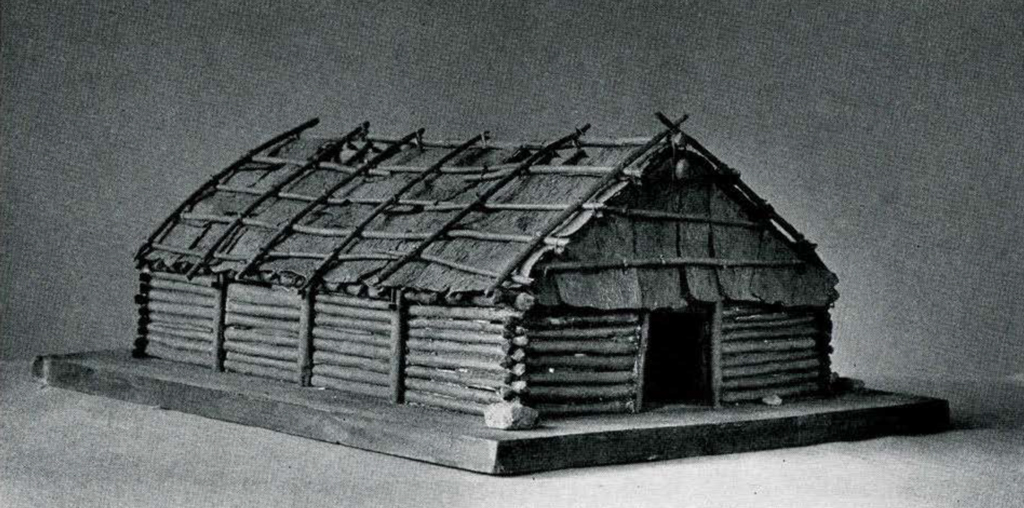

While not all extended families choose to express the solidarity and continuity of the group by inhabiting a single communal dwelling, the practice frequently occurs. Perhaps the best known example of the communal dwelling among American Indians was the Iroquois Longhouse (Plate IV). This house was a log structure of rectangular shape with a door at either end. These served for entrance and exit to and from a central corridor running the full length of the long house. Located along the corridor was a series of hearths, each of which was the focus of living for the restricted family of each conjugal pair. Several such restricted families composed the extended family or lineage occupying the Longhouse and forming the household. This consisted of a parental pair and their unmarried children and the married daughters with their husbands and children. Sons on marrying had moved to the Longhouse of their wives’ families.

Measured by our standards, this type of dwelling would be far from ideal. The Longhouse afforded less privacy to the married couple than we require for family life. Furthermore, few American husbands would feel at ease living in such close proximity to their mothers-in-law. However, it should be remembered that the Iroquois husband, though living with his wife’s people, maintained close ties with his own family (that is, his family of birth). Very frequently he took his meals with his mother in the house of his own lineage, and in the event of a marital spat, he was always welcome either at his mother’s hearth or the hearth of a married sister. Despite disadvantages from our point of view, there were unquestioned advantages to life in the Longhouse. There was never any problem in finding “a sitter” when mother had to leave baby at home. Grandma or another sister was always available. Mothers and daughters worked together on many household tasks and thereby lightened the monotony which many American housewives find in housework. Lastly, and quite important, if a marriage failed both spouses found it far easier than is possible under our marriage system, to return to the status of single blessedness and yet provide for adequate care and socialization of children.

During the foregoing discussion, the American family system has frequently hovered on the periphery of our interest. A more direct reference to the contemporary American family and housing may be made. During a lifetime we live in two families. We are born, reared and educated and until marriage remain in what has been termed the “family of orientation.” Sometime after maturity most individuals marry and establish the family of procreation. The emphasis in our society is strongly in the direction of separation between the two families. Nothing so adequately symbolizes the independence of the family as a dwelling of its own. While parents see the home gradually empty as one by one sons and daughters marry, to suggest that the married couple come home to live would be interpreted by the child and society as a suspicion of inability to care for himself. Such an admission offends against the ideal of independence which is one of the foundations of our character structure. Likewise when parents are neither financially nor physically able to maintain their own home, it is only with extreme reluctance that they accept living with a married son or daughter as a solution to their problem. In view of these characteristics of the American family, it is readily apparent that the “doubling up,” which has been a necessity in recent years for many families as a result of the departure of husbands for the armed service and the shortage of houses, has been a serious problem. The inescapable solution of sending a wife home has been either consciously or subconsciously a humiliating experience for the G.I. To return and find no house for a home of his own aggravates an already existing sense of injustice.

Image Number: 13381

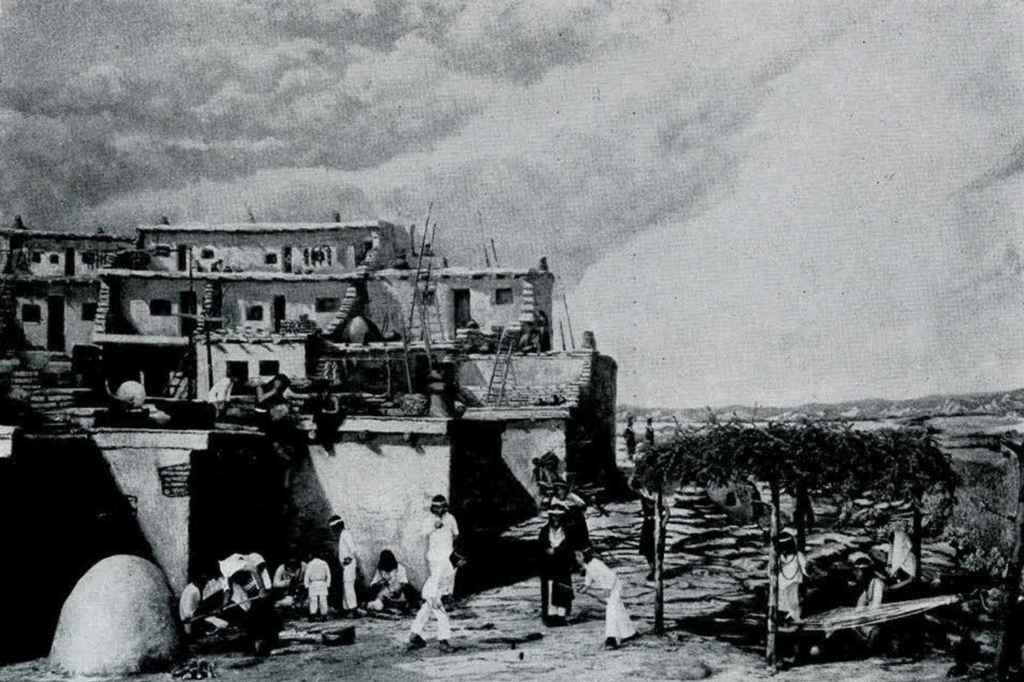

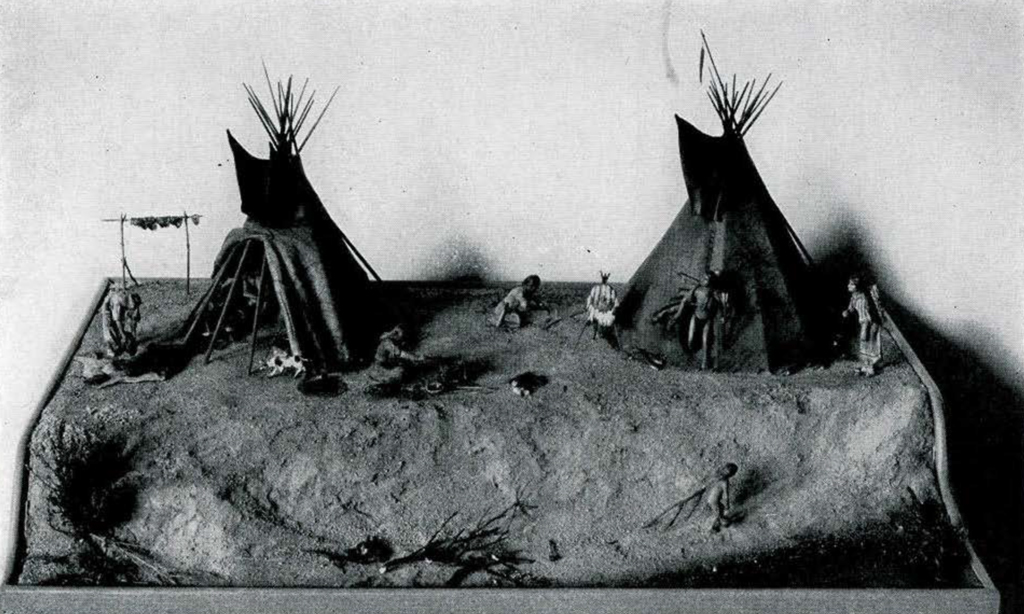

In different societies and at different periods in the history of a single society, the functions performed by a family vary greatly and, in response to changing patterns of family activity, houses likewise undergo changes in design. All families have an economic function. The particular form of economy by which the family satisfies its material needs often plays a major part in the type of house the family builds. In the main, houses are classified as permanent and fixed abodes, and temporary or transportable dwellings. Temporary dwellings correlate with the necessity for mobility of the family in securing a livelihood. Thus the skin-covered tipi of the Plains Indian hunter (Plate V), the felt kurd of the Asiatic pastoralist, the Gypsy’s wagon, the houseboat on the Mississippi and the war worker’s trailer all reflect a nomadic type of economic pursuit. The homes of agriculturists supply the best examples of the fixed abode (Plate VI). There is a sense of permanency and continuity of residence which often seems to be rooted in the soil they till.

Houses of a temporary character have to possess certain qualities. Usually they are more compact in design than permanent dwellings and wherever or whenever climate permits many activities such as cooking can be carried on in the open to save space. Most important is the ease with which they may be dismantled, transported and reassembled. This requires that the framework and the covering of the house be separate. Thus when moving the tipi, the skin cover is taken from the poles, the poles tied at one end and this end is placed on the back of the horse, the other end being left to drag on the ground. This forms a triangular platform over which the cover is placed to form a sort of carrying basket in which household goods may be packed. Permanent housing, on the other hand, is generally constructed so that the frame and covering of the house are inseparable and the latter sometimes lends greater strength to the dwelling (Plate I).

Where houses serve as places of business either for home manufacture, craft work or a business office, not only must space be provided for these activities but it is desirable to separate these parts of the house from those reserved for the more intimate aspects of family living. The Roman patrician whose house served as a business office for meeting clients clearly set off the atrium or public part of the house from the living quarters of the family. The economic activities carried on in the home of the guild master of the Middle Ages were extremely varied, the front room and even the entire lower story being used as a manufactory, a sales room and a place for training apprentice craftsmen. In the homes of colonial America the occupants were engaged in producing many articles for home consumption. The kitchen being a favorite workroom, this room was thus of necessity larger than is needed today when its function has been reduced to the preparation of food.

Image Number: 12896

The smaller homes so fashionable today largely reflect the greatly reduced functions of the American family. The accessibility of stores has eliminated to a large degree the storage of any considerable quantities of food in the house. Many housewives eliminate a laundry room by sending the washing to a public laundry. The spinning wheel is now only an ornament and the sewing machine rarely supplies any considerable part of the family’s clothing supply. As a recreational center, the home has lost many of its functions to the Y.M.C.A., the movie theater and the night club. More and more people enter and leave the world in hospitals. This streamlining of family functions is attributable to the American belief in the inherent superiority of specialization. Unfortunately some are inclined to mistake the elimination of many home functions as an evidence of family decline, as a lessening of the importance of home and houses. This is not necessarily so. Today the housewife is a home manager rather than a person of all work. She is purchasing agent rather than producer. The wise selection of food, the choice of the best in clothing, knowing the best place to go for a good time, all require knowledge of homemaking equal to that Grandma possessed. However far we may have roamed from the ideals of homes and houses of former years, it is still true that “there is no place like home” and this fact is the best possible evidence of its undiminished significance in our social pattern.

In all societies characterized by any degree of class stratification, the house may serve as a symbol of its owner’s rank in the community. When the Irish-American speaks of the “shanty Irish” and the “lace curtain Irish,” he unwittingly exposes the two means by which houses give expression to status. In opposition to the one-room shanty stands the multi-roomed mansion, and thus differences in size alone may serve as an index of position. In singling out lace curtains as symbolic of high status, it is the intention to generalize on the use by members of the upper class of decorative elements in house construction and the equipping of their homes with luxurious furnishings.

While houses always combine size and luxury as a means of status expression, whether in our own or some primitive culture, they are rarely given equal emphasis. Where high rank is accompanied by expansion of the polygynous family, it is quite necessary to display one’s affluence by enlarging the dwelling. Among those Seminoles of Oklahoma who have acquired wealth from oil lands, large, well-constructed brick houses of a size equal to those of Whites of equivalent status are common. However, since they have failed also to adopt from their white neighbors the elaborate appointments which in our society accompany fine housing, the interiors of their homes display only slight, if any, differences from those of the less fortunate members of the tribe. Recent housing trends in the United States clearly suggest that size is gradually being abandoned as a means of expressing social position. High taxes, changing patterns of entertaining, and the recent scarcity and the expensiveness of domestic servants are some of the factors motivating the change.

Image Number: 12999

House decoration as an expression of status may emphasize the historicity of the family or merely convey a sense of comfort, luxury and good taste. Where society emphasizes family as a vehicle for securing social position, furnishing the home with antique pieces is a fitting reminder of this fact. If wealth is the chief criterion of rank, then the more luxurious and modern the furnishings, the better they set forth the owner’s position. Neither of these means of expressing status operates independently. However, the furnishings in a period home and a modern penthouse unmistakably bespeak two divergent approaches to the expression of prestige.

To conclude our discussion, it might prove enlightening to request a simian relative to evaluate the human housing complex. The ape might assure the interviewer that he was duly impressed by the dwellings erected by man; however, he would probably fail to add whether his impression was favorable or unfavorable. He might single out as being of particular interest the great size of houses, their wide range of architectural design, the diverse materials employed in their construction, the extensive use of ornamental features, the creation of specially designed rooms for various home functions (kitchens, dining rooms, baths, bedrooms, game rooms, etc.) and the large number of gadgets and pieces of furniture which cluttered the interior of the house. When pressed for an evaluative opinion of the features he had enumerated, he could readily admit that it appears that humans go to a great fuss in satisfying a few simple needs.

At this point we would feel compelled to remind our relative that his opinion unfortunately reflected the simian point of view, by which dwellings are judged merely on the basis of their utility in satisfying certain needs necessary for survival. Were it possible for him to acquire the hominid outlook, he would doubtless appreciate that man as a cultural animal had to satisfy the needs and wants of a social environment in addition to those imposed by conditions of the natural environment. Thus, in erecting a house, it was necessary to embody features providing for man’s comfort, his need for esthetic satisfaction and his desire to express his position in the community.

More than likely, our simian cousin could rather slightly inquire about the many members of the human race who he was led to understand were without a means of satisfying even the elemental needs for survival. This unfortunate remark could be countered by explaining that this was also a cultural phenomenon adequately explained by other cultural creations known as economic laws. Lest he fail to appreciate the significance of this explanation, he could be assured that the housing crisis was only temporary and would shortly be solved by a cultural invention known as the Government-at least that we hoped so.

J. A. N.