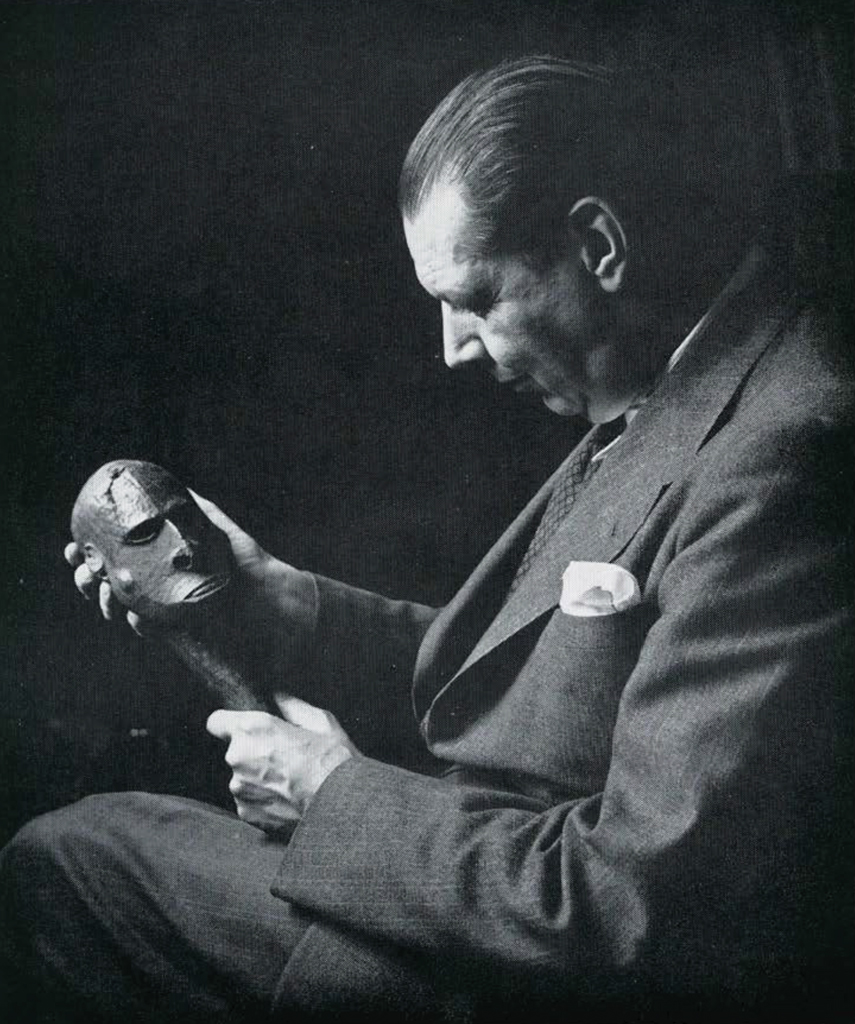

Mr. d’Harnoncourt chose a Sepik River wood sculpture from New Guinea.

That is a fine thing without any qualification.

I have never seen anything from Oceania that is such a personal work of art. It is one of the most extraordinary examples of the so-called prime art, because it combines, within a clearly defined style, all the characteristics of individual perception that we usually claim for Western art after the Renaissance.

The head is obviously a portrait, but shows such a strong handwriting that I feel sure that if I ever saw another work by the same man I could recognize it as such.

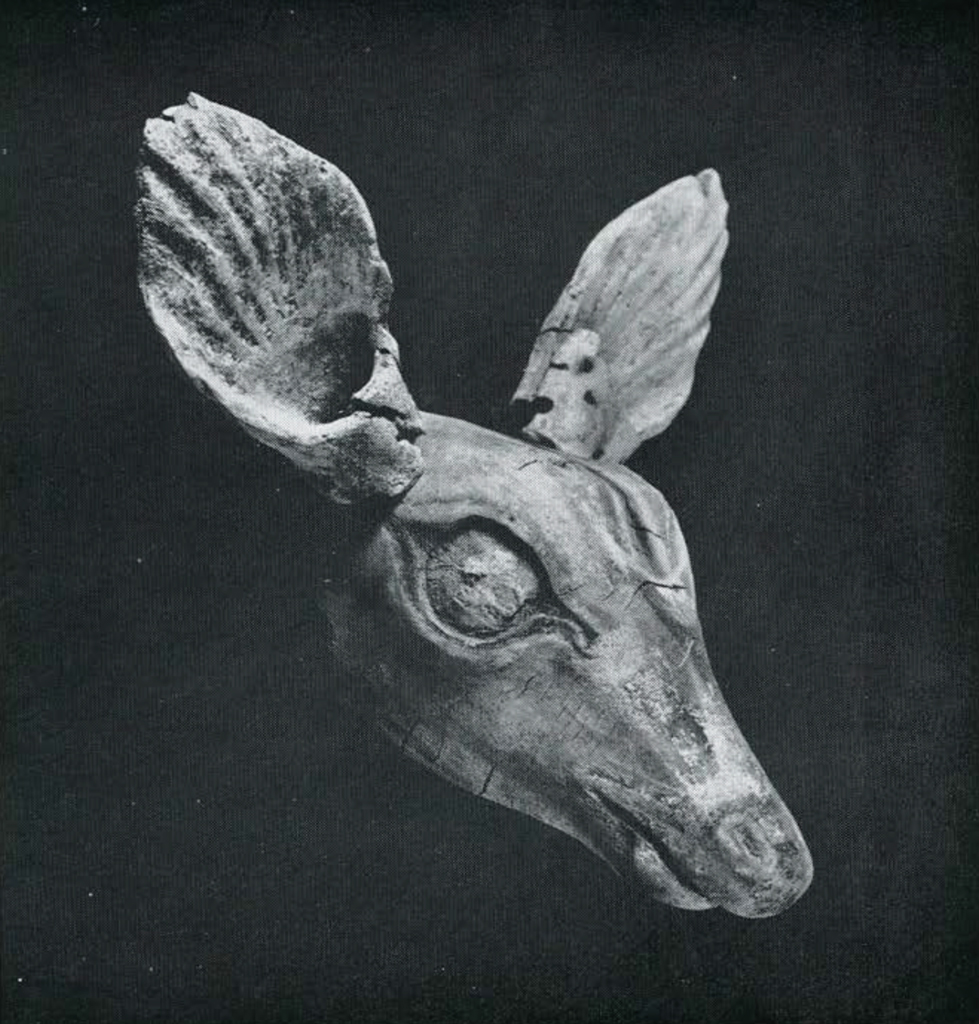

This rare carved deer’s head of the 12th or 13th century A.D. excavated, under water, by a museum expedition off Key Marco, Florida.

I selected the deer head because it is the finest example of realism in American Indian art. The sensitivity of rendering, the delicate curves and surfaces of the deer head, the loving care given to the outline of the eyes and the shape of the ears make one feel as if one were dealing with a living creature.

In spite of the startling likeness, the piece has none of the dryness that we usually associate with a painstaking imitation of nature. It was obviously done by someone who had a great tenderness and admiration for animals and who was able to make the sculpture reflect his own feeling toward the subject matter.

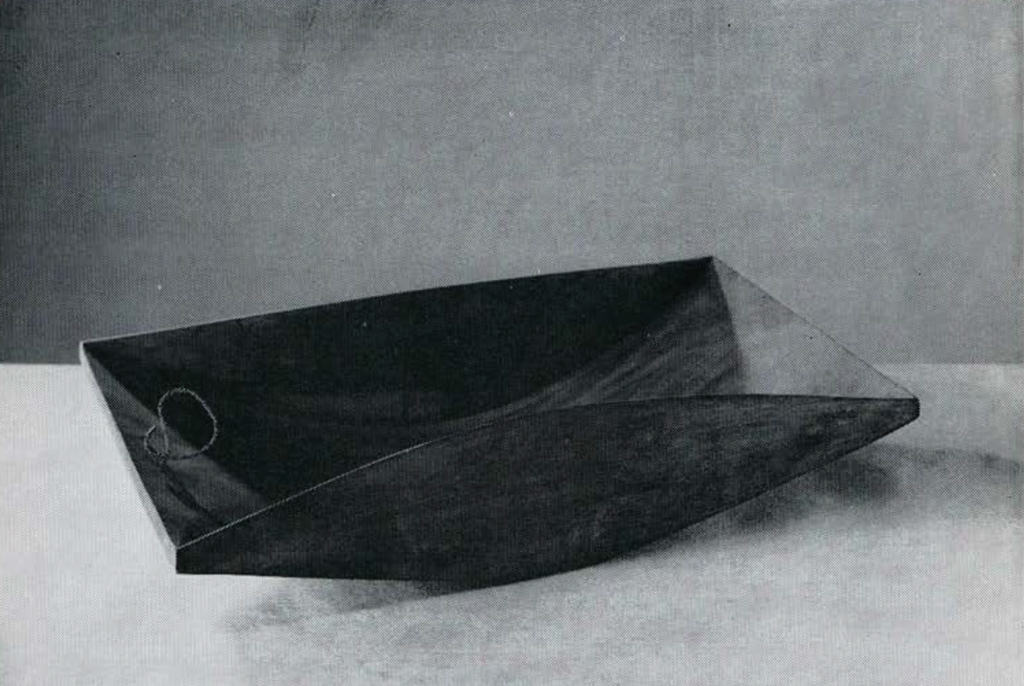

And a wooden bowl from Micronesia.

The food dish from Macey Island is a very fine example of primitive art deriving its beauty entirely from perfection of proportions without the help of surface decoration or elaboration.

In this sense the bowl compares favorably with some of the best produces of modern industrial design.