Mr. Kirstein was the only selector to choose a piece from the Museum’s large New Ireland collection. Of this dance mask, he said:

Being neither an art-historian nor an anthropologist, the galaxy of objects in the reserve collections of the University Museum attract me primarily as having links with my own work, which is in the theatre in general, and in the ballet in particular.

This magnificent ritual headdress combines in its monumental crest the human and the aerial. Human dancers, hopefully but helplessly, must always dare to assume the quality and compete with the power of birds. Flight and the denial of gravity, fluttering, soaring, stalking and pecking, are all parts of an aviary language which, based on the observation of birdy movement, has, over many centuries and in many cultures, been absorbed into the idiom of the academic dance. In this mask, the bird spread-eagled across the carved biped’s countenance forms for me an ancestral image of the greatest of Western European dance-dramas in the classic tradition: Tchaikowsky’s “Lac des Cygnes,” in its recent brilliant metamorphosis, “Swan Lake” by George Balanchine.

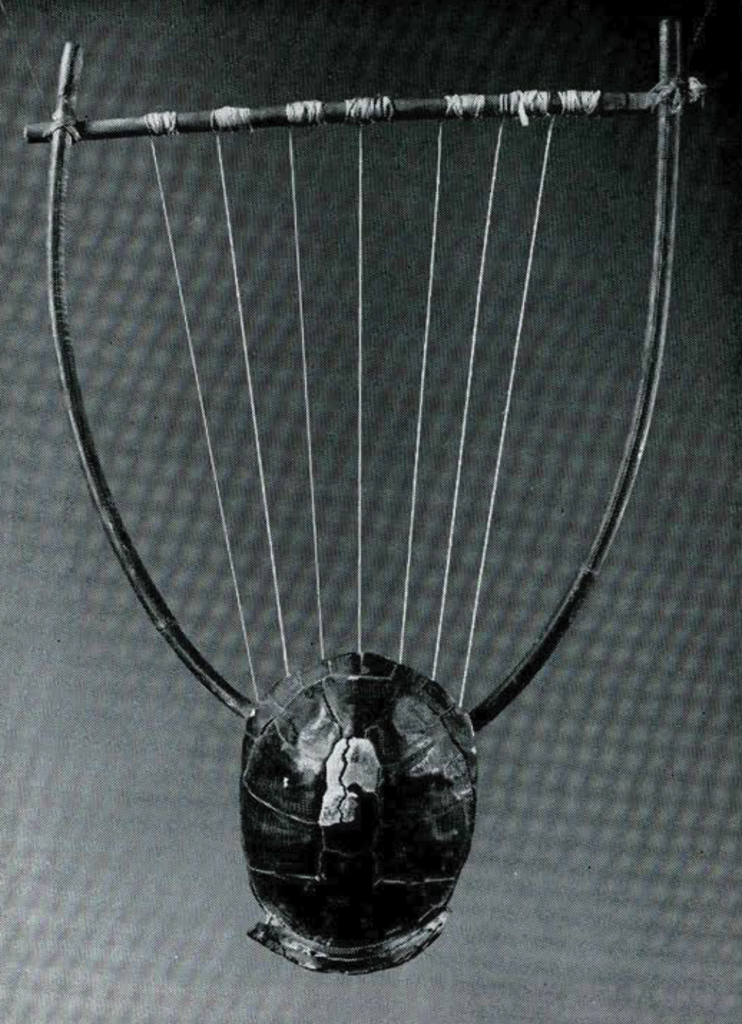

He chose a tortoise shell konttho from Sherbro Island, Sierra Leone.

This basic, elegant instrument, ancient sign of Orpheus’ gift of song and all poetry, epic, lyric or dramatic, is the irreducible inspiring or accompanying viol. Grandfather of all stringed pieces, source of the orchestra, root of symphonic music, this lyre, or others of its type in many far-flung sections of the world, belonged to all the earliest gods and many of the first hero-artists. Without it, no priest or dancer could have developed a very expressive song or dance, for which mere drum-beats are only a metrical blood-count.

The turtle’s sounding board and the vibrating thong, gut or reed, stretched across it, prefigured the pianoforte and all the silken string-sections of our symphonic bands.

And the carved figure of a hornbill, Dyak, from Borneo.

This thrilling silhouette, composed of sharp, cursive shapes which backtrack and reverse, composes a fierce hard plumage, enforcing both the flight and the song of a jungle soprano in its strict visual cadenza.

Taken out of its context, like a bird in a cage miles away from its hot jungle damp and heat, nevertheless this fiery beaked spirit is the essential fierce model of one kind of theatrical force, the opposite of the cool Swan Princess.

Here is the progenitor of Stravinsky’s Jar Ptitza: the Bird of Fire.