Some of the finest of the University Museum’s collections come from New Guinea and the adjacent islands. For some time, however, the Museum’s research programs have been focused on other areas. Last spring it was decided to look into the possibilities for resuming research in the Western Pacific. To this end I spent the three months of October, November, and December making an ethnographic survey of the territories of Papua and Australian New Guinea. The survey was jointly sponsored by the University Museum and the Department of Anthropology. Its purpose was to select an area where research would be not only feasible but most rewarding to the Museum from the standpoint of its program of promoting work in areas which are of prime importance for major problems in ethnology and archaeology.

On many counts New Guinea and its adjacent islands form a region of outstanding interest. It is dramatic in the variety and color of its landscapes and peoples. Though, ethnologically, it is one of the least known areas of the world, it has, paradoxically, provided some of the finest ethnographic studies. The works of Malinowski on the Trobriand natives and of Williams on the Orokaiva tribe are two outstanding examples. We know a great deal about native life in a few scattered tribes, but relatively little as to how they fit into the total picture. As yet we can only guess at the area’s history. If our knowledge of North American Indians were based on brilliant studies of the Iroquois, Kwakiutl, Zuni, and Pomo, surveys of the lower Mississippi Valley and the Southeastern United States, solid but less outstanding studies of the Hopi, Nootka, Haida, Creek, and Seminole, fine collections of Northwest Coast art, a number of travel and missionary accounts of life in the northeastern woodlands, a few reports by prospectors and explorers for the plains and Rocky Mountains, and no archaeology other than surface collections from a few mounds, then it would be analogous to our present knowledge of the natives of New Guinea.

Until twenty years ago virtually nothing was known of New Guinea’s vast mountainous interior. In 1933 it was discovered to contain a very large native population dwelling in extensive valleys in the highlands along New Guinea’s mountain backbone. In fact the highlands contain the heaviest concentration of native peoples in all of New Guinea. The war stimulated the opening of this region, which is now studded with landing strips for small aircraft.

Because it has such a large population (estimated at one and a half millions) and has only recently been opened to Europeans, our original plan was to concentrate our survey in the highlands. On arriving in Australia, however, I learned that the Australian National University is launching a program for systematically covering the ethnology of a large portion of this region and that other institutions are also drawing up plans for doing work there. I decided, therefore, to alter my itinerary to include only the western part of the highlands and to extend the survey to cover other areas which have been exposed to Europeans for a much longer time, but about whose ethnology we know relatively little.

As finally organized, therefore, my itinerary went as follows. After spending a week in Port Moresby making arrangements with government officials, I went by Catalina sea plane to Rabaul, New Britain, where I had an opportunity to see something of the fairly heavily acculturated natives in its environs. From there I went by the same aircraft to Talasea, on the Willaumez Peninsula in the central part of New Britain’s north coast. Here I spent two weeks surveying the coastal tribes to the east and west of Talasea. I then picked up the fortnightly plane and flew around the rest of New Britain back to Rabaul.

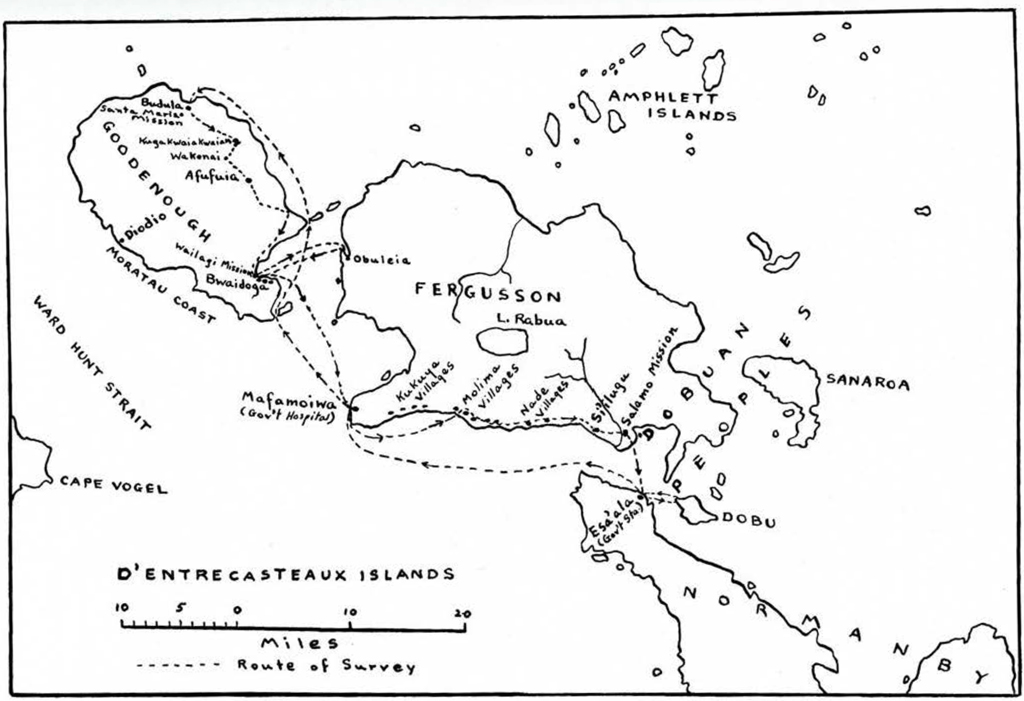

The next area investigated was the D’Entrecasteaux Islands. The plane dropped me off at Esa’ala, the government station on Normanby Island. During the next two and a half weeks I managed a short visit to Dobu, and a two week hike over Goodenough and Ferguson Islands. This was followed by a plane trip around the Massim region, with a night in the Trobriands and a breathtaking view from the air of the Louisiades. A mixture of small high islands, coral atolls, and magnificent reefs, the Louisiade Archipelago cannot be matched for beauty anywhere in the Pacific.

My itinerary then took me to Lae on New Guinea’s west coast and thence by small plane to Wabaga in the Western Highlands. The population here shows a great deal of uniformity over a wide area. Instead of making an extensive survey, therefore, I spent my week at Wabaga collecting as much information as possible on the culture of the local natives.

The last region visited was the Kukukuku Mountains in the southwestern corner of New Guinea’s Morobe District. This is completely wild country, containing one isolated government post established only a year ago. The nearest native villages are close to a day’s walk from the government station at Menyamya. My week here was spent on a patrol to two villages. It was necessary to visit them in the company of a government officer and an armed police patrol, since the natives are not yet pacified and have no fondness for strangers.

Throughout the trip I enjoyed the full cooperation of Australian government officials. Without their assistance it would have been impossible to survey the areas visited. They expressed an active interest in any plans for extended ethnological work which the Museum may undertake in Papua and New Guinea, and impressed me as willing to cooperate fully.*

New Britain

New Britain is about three hundred miles long by fifty miles wide and has a land area of approximately fourteen thousand miles. The earliest missions and trading posts were established at the extreme northeastern tip and in the Duke of York Islands between New Britain and New Ireland. Considerable ethnographic information is available on the tribes in its vicinity, but the rest of the island, with the exception of only one or two tribes, has remained terra incognita to this day. A few scattered plantations along the coasts, and the government posts at Talasea and Kandrian represent the extent of European penetration. Experience with Europeans is otherwise confined to occasional government and mission patrols, visits by labor recruiters, and a year or two of work by young men cutting copra on one of the plantations. Japanese, Australian, and American soldiers created temporary opportunities in the coastal communities during the war. They served to modify pre-existing attitudes towards Europeans to some degree but had little other effect on the natives, except to make them less satisfied with their place in the world.

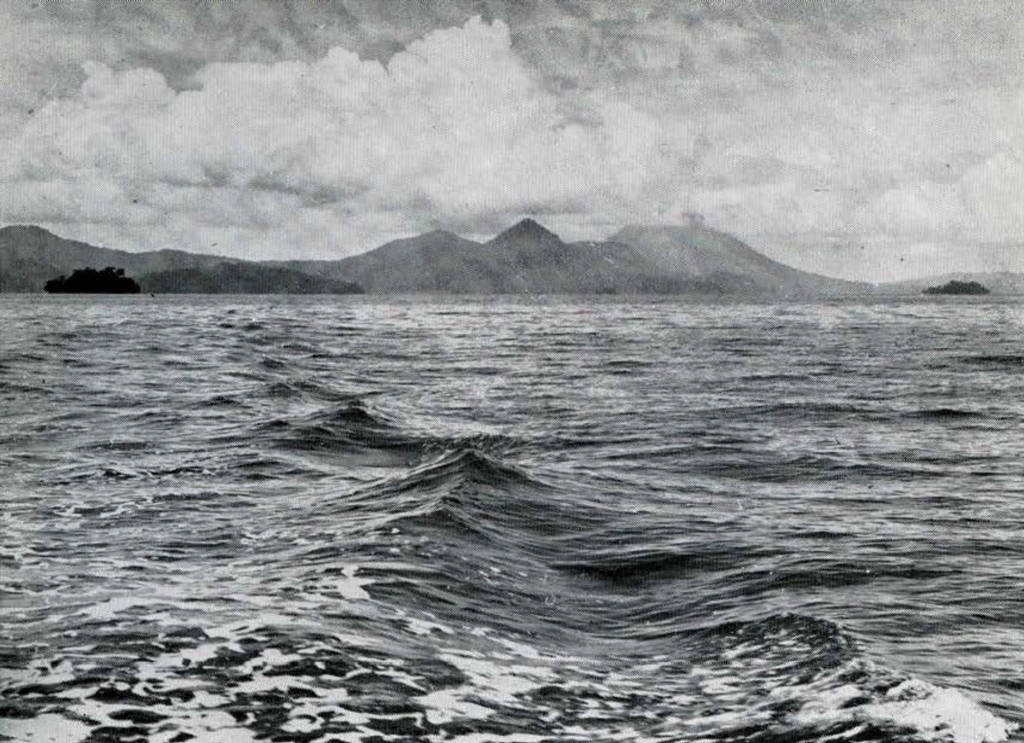

New Britain’s native population is divided into a number of small tribes. Most of those along the coasts speak Melanesian languages, which means simply that they are members of the Malayo-Polynesian linguistic family. Languages spoken by the interior tribes are entirely unrelated, being classed as Papuan, a term which implies little about their actual relationships. The Melanesian-speaking tribes are newer arrivals. Just when they came out of Indonesia is not known. It is clear, however, that they have been coming in small groups for a long time, occupying the smaller islands and sections of coast on the larger ones. In places they have adapted themselves to inland living, but have for the most part retained their maritime orientation. As immigrants having to adapt themselves to new surroundings under varying conditions, Melanesian tribes have exhibited a tendency to specialize in various ways. The result is considerable variation of local cultures. Because of their maritime traditions they have engaged widely in trade; and ceremonies as well as artifacts have been bartered over wide distances, adding to the similarities already provided by their common heritage. Mobility of population has been augmented in New Britain because of the instability of the island itself. Heavily volcanic all along its northern coast, its topography is continually shifting. In 1879, the Willaumez Peninsula was a series of islands. They were subsequently united with each other and with the mainland as a result of volcanic disturbances, of which the natives have clear memory (Fig. 1). Cycles of volcanic activity have unquestionably produced correlated cycles of depopulation and repopulation in many localities along New Britain’s north coast.

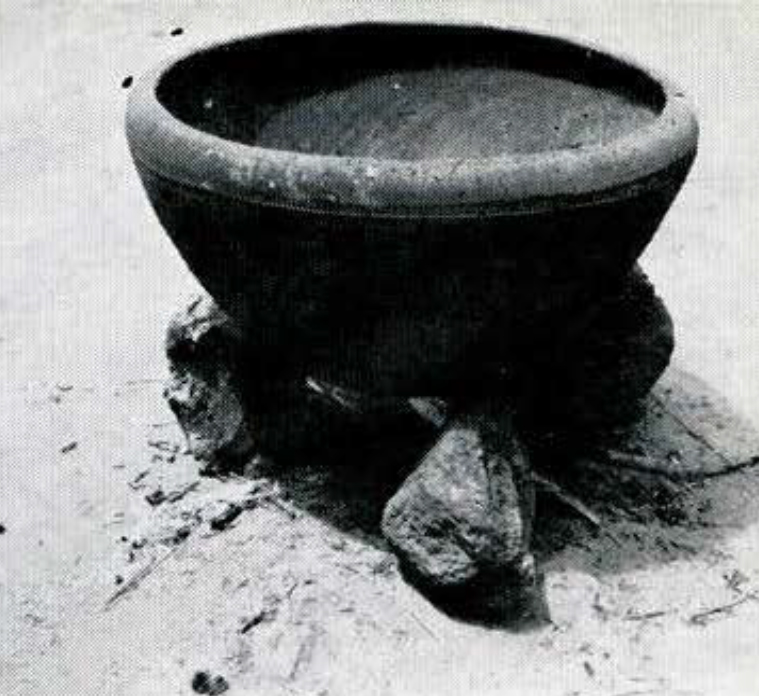

Surface finds on the Willaumez Peninsula and adjacent mainland reflect this instability of population. A number of stone mortars and pestles have been found by natives (Fig. 2). They disclaim any knowledge as to what they are and maintain that their ancestors neither made nor used them. Similar bowl-like mortars of stone are said by natives in the Witu Islands to have been the mirrors of their ancestors, because they reveal one’s reflection when they are filled with water. The Witu Islands contain large human heads cut in stone, which the natives also attribute to their ancestors. There are additional bits of evidence in other parts of New Britain’s north coast for an earlier population, which, whatever it was, is not likely to have been ancestral to the Papuan-speaking tribes of the interior.

The tribes which I was able to visit on my survey were the Koobe (Kombe), Bakovi, West Nakanai, and Banaule. The Koobe live on a series of tiny islets off the coast to the west of the Willaumez Peninsula. They are primarily a fishing and trading people-though they keep gardens on the mainland-and have a reputation for sharp dealing among their neighbors.

The Koobe are divided into five patrilineal sibs, kin groups in which membership is based on descent in the male line. They are locally represented in the various villages by lineages, whose men, with their wives, occupy neighboring houses. According to tradition, the founding ancestor from whom all Koobe are descended came with his family in a canoe to a point on the mainland some distance west of their present location. He brought with him pandanus and betel, which he planted there. Later, because of difficulties with the Bariai Tribe, whose close neighbors they were, the Koobe moved to the small islands which are their present homes. One Koobe village remains far to the west of the others on an island off the Bariai coast.

Each lineage has a men’s house where the unmarried men sleep and where the married men spend much of their time. The ground behind it is taboo to women. It is here that secret parts of the rites initiating boys into adulthood are performed. Masks and other ritual paraphernalia are kept in the men’s house (Figs. 3, 4).

Little boys go naked and little girls wear a wisp of grass. More substantial grass aprons are worn by older girls and adult women. Women are heavily tattooed and girls paint their faces orange and white. When they reach puberty, boys are circumcised. Their ears are slit and noses pierced as well. All men wear a tribal mark consisting of a double row of dots tattooed around each eye. Their clothing now consists of the conventional kilt or “laplap” of imported cloth.

Ceremonial revolves around initiating youths and honoring the ancestors. For these rites impressive platforms are erected with posts carved and painted to represent fish (Fig. 5).

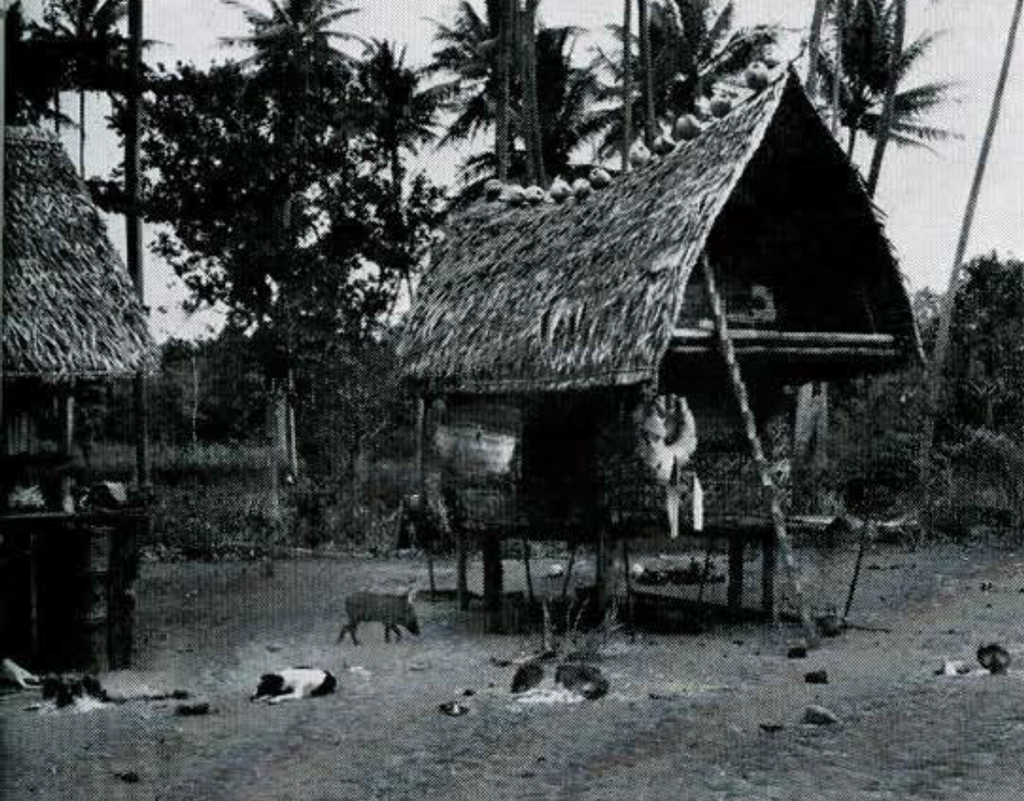

The Bakovi occupy a number of villages scattered over the Willaumez Peninsula. Their economy is oriented primarily towards gardening and the raising of pigs. They build their small thatched houses on piles. As with the-Koobe, the men of a patrilineal lineage occupy a cluster of such houses (Fig. 6), several such clusters forming a village. There are men’s houses for the unmarried youths, who once past puberty are forbidden to sleep in the same house with their sisters. A year-long cycle of rites for the ancestors forms the chief religious festival. There are also graded men’s societies among the Bakovi, with pigs playing a prominent part in the associated rituals. Until recently, the upper arm bones of a dead man were taken from his body and kept as family fetishes.

The extreme end of the Willaumez Peninsula was formerly a separate island. It belongs to the Bulu Tribe, which at present occupies two rather widely separated villages. In contrast with the Koobe and Bakovi, Bulu kin groups are based on descent in the female line. Until about seventy years ago, the entire tribe occupied a single large village on the northwest coast of the peninsula. They are said to have been decimated by small-pox or measles, the survivors moving to their present location. Abandonment of the old village may have been caused by the volcanic disturbances which created the peninsula.

In the bush behind the Koobe and Bakovi is a small tribe, which Father Hagan at Talasea cans the Kendo People. He has visited them on two separate occasions, being one of the very few Europeans to have penetrated their country. He estimates their population at about eighty people. They live in two or three small scattered settlements and range over a wide area in what appears to be a semi-nomadic fashion. Each tiny village is protected by a barricade of felled trees. The trees are cut to fall out from the center where the houses are built, so that the village is hidden behind an impenetrable screen of branches on all sides. There is just one concealed path into the village over the logs. The young men do not marry until after thirty years of age, remaining in military barracks until this time. The only occasion on which all the Kendo hamlets get together is to celebrate the funeral rites of an important man.

The West Nakanai number about two thousand people inhabiting eighteen villages along the coast across the bay to the east of the Willaumez Peninsula. The population is divided into over twenty matrilineal sibs. The villages are neatly laid out with the houses forming straight rows on either side of a wide “village street.” Many of them have attractively painted walls (Fig. 7). Each village has one or more men’s houses which are taboo to women. At puberty, the boys have their ears slit and noses pierced but are not circumcised. Initiation rites are not so elaborate as among the Koobe and are mainly a family rather than a public affair. In former times, the dead were buried under their homes; and funeral rites, mourning ceremonies, and ancestor worship were highly elaborated. The West Nakanai have been subject to mission influence for a considerable time, but some of the former ritual is still carried on. The upper arm bone of an important man no longer is used in his funeral rites, but a cassowary thigh bone has been substituted. Elaborately carved and painted shields, rimmed with white feathers, are among the more colorful objects still being made (Fig. 8). They are used in dancing and as part of the payment which a man makes for his bride. Shell money is also important for the bride-price that is customarily paid among the Nakanai and other tribes in the Talasea region.

The West Nakanai are of special interest at the present time because of a strong nativistic movement. Movements of this kind have developed in many parts of the world as a reaction against Europeans and outside dominance. In New Guinea they began to appear before the war in a form which has given them the name of Cargo Cult. While Cargo Cults vary a great deal locally, they usually start with the emergence of a native prophet who claims that the ancestors, or some other divine agent, are going to send a great ship laden with all kinds of European cargo which will be distributed free to the natives. A new era will follow in which natives will have equal status with whites or in which whites will be driven from New Guinea. In the past decade Cargo Cults have sprung up among a number of tribes in the New Guinea territory. The West Nakanai are one of them.

The Banaule tribe consists of just one village to the west of the Nakanai, and does not number more than 150 people. It operates as a constituent village of the Nakanai as far as its sibs and ceremonies are concerned, but is of interest because of its language. It is completely different in this regard from any of its neighbors. While its language appears to be Melanesian rather than Papuan, it differs from other Melanesian languages in a number of respects. The Banaule merit linguistic study as possibly representing the last survivors of a distinct branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language family.

Beyond these tribes are many others of considerable interest. In the interior are the Sengseng, a strong bush people who try to keep Europeans out of their territory as much as possible. To the west of the Koobe are the Kaliai and Lamogai, riverine peoples who are visited but rarely and have never been subject to mission influences. To the east of the West Nakanai are the so-called Inland Nakanai, unmissionized, living in fortified hill villages. Beyond them are further coastal peoples, the inland Kaulaung, and a little band of renegade Bainings, called the Mokolkol, who until a year ago terrorized their neighbors on the north and south coasts by the sudden surprise raids which they perpetrated. In the extreme west are the Kalenge, builders of great canoes, and to the southeast of them the Arawe peoples, who bind the heads of their infants to elongate them, and who used to kill all widows by strangulation.

THE D’ENTRECASTEAUX ISLANDS

The southeastern tip of Papua together with its numerous adjacent islands culminating in the Louisiade Archipelago forms a region known as the Massim. Except for Rossel Island at the extreme end of the archipelago, all of the natives in the Massim are Melanesian-speaking. Moreover, the numerous dialects and languages show sufficient similarities to form a distinct related subgroup within the larger Melanesian stock, though the language of Tagula Island seems sufficiently distinct to be classed separately from the others. Our knowledge of this area is based on a survey by Seligman, Malinowski’s brilliant studies of the Trobriand Islands, Fortune’s book about the small island of Dobu, a preliminary study by Geness and Ballantyne of the people of Goodenough Island, and Armstrong’s study of native money on Rossel Island. Recently, Cyril Belshaw surveyed the Milne Bay tribes, but the results of his work have not as yet been published. The entire area is closely linked by complicated trading arrangements, the best known and most important one being the Kula exchange, described by Malinowski. Because of this, it would be of great value to ethnology to complete the work so well begun by undertaking a series of ethnographic studies of the many other Massim tribes. It was this consideration which led to including the D’Entrecasteaux and Louisiades in our survey. Unfortunately time and transportation made it necessary to abandon plans to tour the Louisiades.

While there are few plantations and only a handful of Europeans resident in the D’Entrecasteaux, the islands have been subject to heavy missionary activity for fifty years. They have also been a popular source of native labor for plantations elsewhere. Many old hillside villages have been moved to the beaches for the convenience of government patrol officers. As a result, the old native way of life has been modified in a number of ways. The war, too, left its scars. A large kunai grass plain on Goodenough Island, for example, used to be a source of game. The establishment of an air base there during the war destroyed its animal life. The absence of resident Europeans, however, has left the way of life thoroughly native, however changed. Nor is the manner or degree of change the same for all tribes. Some groups in the interior of Fergusson Island have been affected very little, while others in the immediate vicinity of mission stations have changed markedly. The total effect, however, has been to deprive the D’Entrecasteaux of many of the more colorful aspects of native life. This may be a superficial impression which greater familiarity with the natives would quickly dispel, but after sampling the sharp flavors of New Britain, my taste of the D’Entrecasteaux seemed by comparison rather flat. They are, nevertheless, extremely interesting and exquisitely beautiful islands.

All of the islands, large and small are rugged in the extreme. Goodenough, the smallest of the three larger ones, shoots up out of the water to over eight thousand feet. Large villages are, therefore, exceptional. The population is divided into many small tribes, each consisting of an aggregate of hamlets whose members speak the same dialect. In former times, each little tribe was chronically at war with its neighbors. Successful raids were celebrated by eating the captives taken. At the same time there were traditional alliances for the sake of trade, which was extensive and which is still carried on.

For protection, settlements were well back from the beaches part way up the mountain slopes. Beyond this it is impossible to generalize about native social organization, which varies widely from tribe to tribe.

On Dobu and the eastern end of Fergusson Island, for example, each hamlet is the property of a matrilineal sib or lineage. When a couple marries, it spends one year living in the hamlet of the wife’s lineage and the next in that of the husband’s. All their married lives, people shift their place of residence every year back and forth between the two settlements.

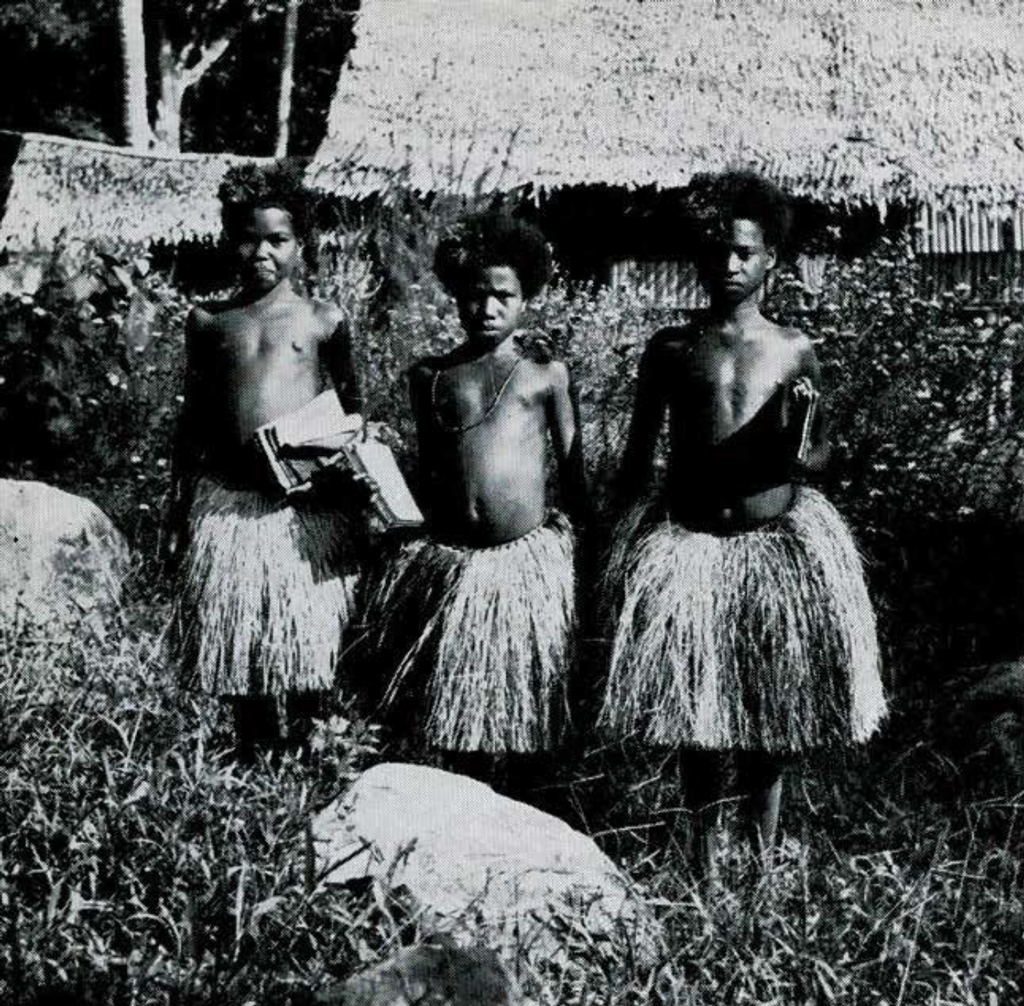

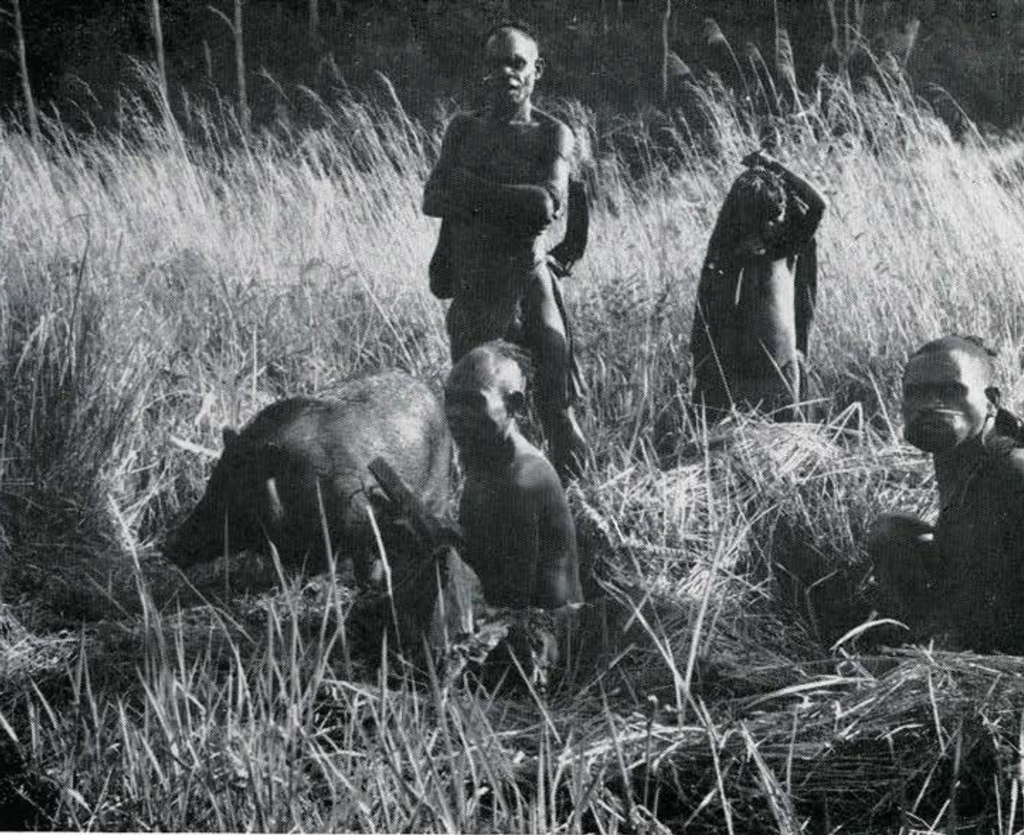

The Molima tribe on the south coast of Fergusson operates in an entirely different manner. It is organized into patrilineal lineages and the men of a lineage live together in a hamlet. But the land where their hamlet is located does not belong to them. It belongs to the children of their paternal aunts. Thus men control the land around the hamlets from which their mothers came, but reside patrilocally with their fathers on land controlled by their cousins (Figs. 9, 10).

The Bwaidogan tribe on Goodenough Island is divided into a series of kin groups called gabu. Membership in them is not based on a rule of descent in either the male or female line. Men are free to choose between their father’s or mother’s gabu, though usually choosing their father’s. Women, on the other hand, normally join their mother’s. Each gabu is subdivided into several family groups called unuma. Each unuma occupies a cluster of adjacent houses surrounding a platform of earth paved with flat stones and equipped with upright stone back rests (Fig. 11). To sit uninvited on the platform of another unuma is to insult its owners. In former times an offender paid with his life.

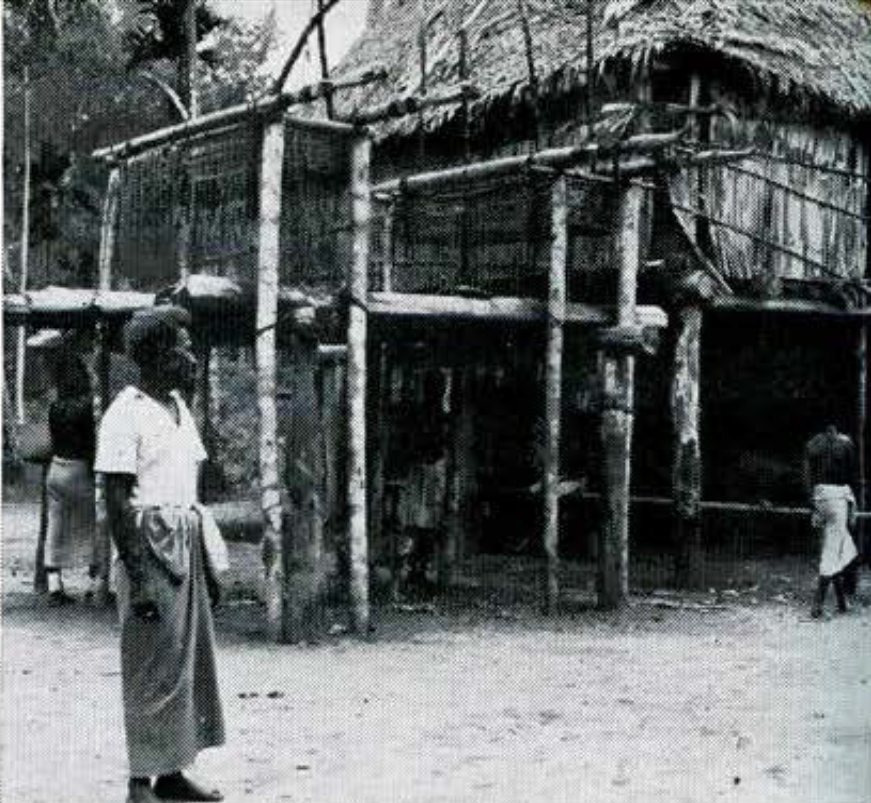

There are only a few places in the D’Entrecasteaux where pottery is manufactured (Fig. 12). The most important of these is the Amphlett Islands. Amphlettese canoes visit the villages on Goodenough and Fergusson bringing pots to trade. One village, Budula, on the northeastern end of Goodenough manufactures its own pottery but does not trade it widely. The type of house built in this village differs from that found elsewhere on Goodenough Island (Fig. 13). The village street also lacks unuma platforms. These differences suggest that Budula represents an intrusive group.

In The Sorcerers of Dobu, Fortune describes the Dobuans as intensely concerned with sorcery, which the Dobuans have developed as the chief form of aggression. This seems to be the case through a large part of the D’Entrecasteaux. Sorcery and poisoning are problems of considerable concern to local government officials.

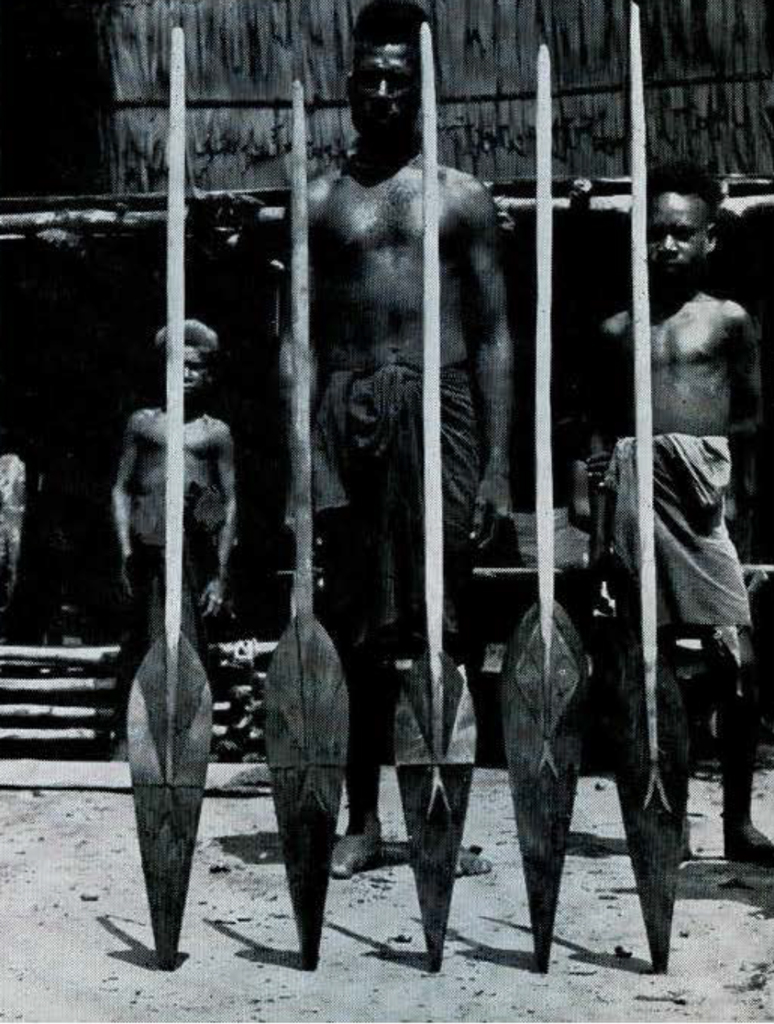

The Massim region is famous for its wood-carving and is one of the chief centers of native art in Papua and New Guinea (Figs. 14, 15). It was gratifying to see that local art work is still carried on. The Trobriand Islanders produce a lot of it now for sale to Europeans. They have adapted their wood-carving to the production of end-tables and salad bowls, objects for which there is a European market. Many of these pieces are done with great care, and compare favorably with older specimens.

THE WESTERN HIGHLANDS

The most publicized part of New Guinea’s highlands is the Wahgi Valley, especially its western end in the vicinity of Mt. Hagen. The Hagen stone axes are now becoming world famous. The demand for them is so great that they are being mass produced for export under the guiding hand of an enterprising trader. Though unknown before 1933, Mt. Hagen has become one of the show places of New Guinea. Already, two valuable ethnographic accounts of its natives have been produced, one by Gitlow, and a three-volume work by Vicedom and Tischner. The government post there has recently been made a district headquarters, administratively comparable to such centers as Rabaul, Lae, and Madang. West of Mt. Hagen, however, stretches a vast hinterland whose exploration has been systematically undertaken only since the war. Immediately west of the Hagen range is the Lai River. Five years ago a government post was established at Wabaga, toward the western end of the valley. It was here that I undertook to get a look at the Western Highlands.

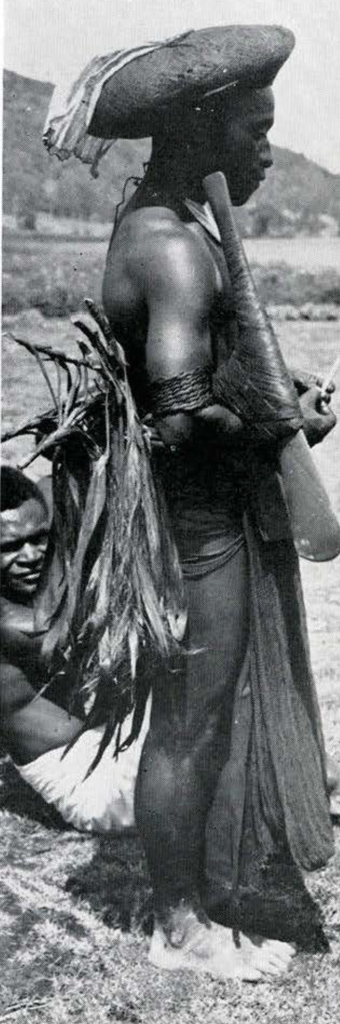

The natives of this area are a relatively short, dark-skinned people. They are part of a large group of related peoples extending westward from Mt. Hagen for as much as seventy miles or more and spreading north and south from the Lai Valley for a considerable distance. They all share a distinctive custom in the elaborate wigs worn by men. They build them up with human hair, obtained from women, which they mat into their own to effect wigs of various shapes. Around Wabaga a mushroom shaped wig is customary. Further westward it is built up to make two knob-like horns projecting from the sides of the head.

In other respects local dress is very much like that in the Wahgi Valley and the Mt. Hagen area (Figs. 16, 17). Men wear a long apron of netting in front supported by a belt. They cover their buttocks with a spray of leaves hooked into the belt by a twig. Ornaments of shell on the forehead and breast are common. Prior to the coming of government officers, men normally carried long wooden spears, some with fire-hardened points, others tipped with bone or with a cassowary claw. Now they carry a stone or steel axe stuck through the belt.

Women wear a knee-length grass apron with a longer, narrower back panel, hanging down like a tail. They normally carry a large bag of netting on the back, suspended from the forehead. They sometimes paint their arms, legs, and breasts with mud in zebra-stripe patterns.

The elevation at Wabaga is 7,500 feet above sea level. The climate is even through the year, the temperature reaching about 70° F. during the clay and falling to as low as 40° F. at night. To warm their scantily clothed bodies, the natives rub themselves clown with pig grease or with a highly valued tree oil imported from the Southern Highlands. To protect their staple sweet potato crop from the cold, they plant in large square mounds of earth mixed with compost. The compost keeps the soil warm enough to promote normal growth.

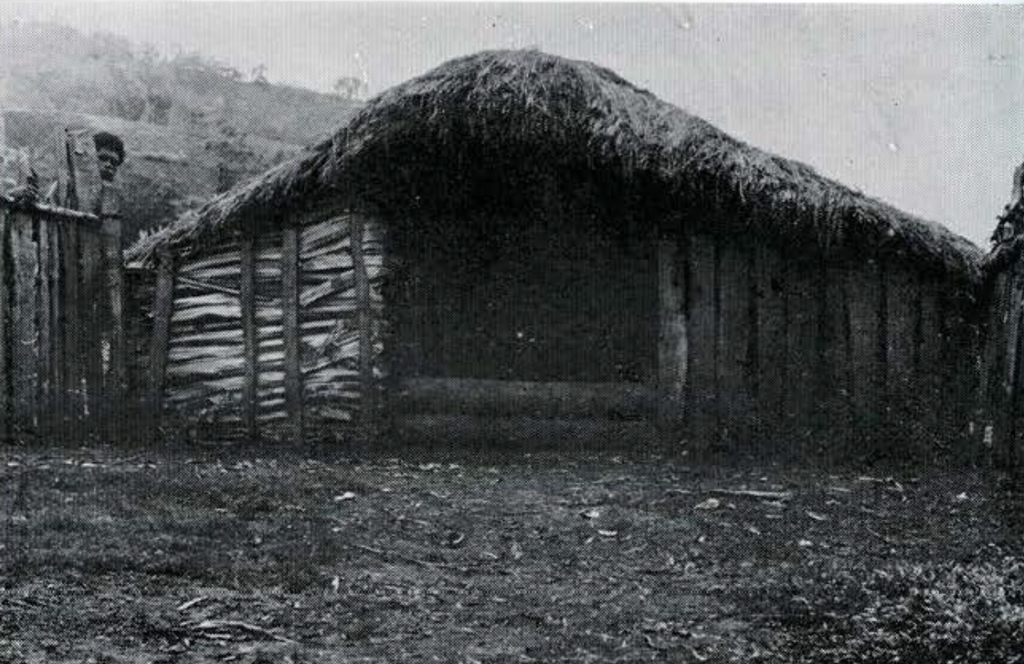

Houses are well built (Fig. 18). The earth floor is covered with a thick carpet of the pulp of chewed sugar cane, which provides a form of insulation similar to saw-dust. Men and women do not sleep together in the same house, even after marriage, but occupy separate quarters. Each of the women’s houses is approached through a fenced courtyard (Fig. 19), and there are special stalls for pigs inside the house.

The Western Highlanders trace descent in the male line. Organized as clans, their descent groups have each their own territory within which the clan members live in scattered homesteads. There are no consolidated villages. Several clans form a larger group with a common ancestor, and each clan is subdivided into lineages. None of these groups is totemic. Each clan has a ceremonial ground, cleared of vegetation. For seating purposes each clan is divided into moieties, which face each other from opposite sides of the ceremonial ground.

Movable property in the form of pigs, stone axes, and gold-lip and bailer shells plays a prominent role in the relations between individuals and groups. Most formal dealings are accompanied by payments or exchanges of these commodities. Birth, marriage and death, all require the gift or exchange of property. Murder, death in warfare, any injury to person or property must be compensated with a payment. Every gift must be acknowledged with a return gift. In the Wahgi Valley there is an elaborate exchange system known as the moka or tei. In the past few years it has extended into the Lai Valley as far as Wabaga, whose natives now participate in the exchanges.

The people of Wabaga believe that all deaths result from unnatural causes. One is always “killed” either by a living person or by the ghost of a deceased relative or enemy. One informant told me, “My grandfather killed my father, my father will kill me, and I will kill my child.” Once a ghost has killed a near relative it is no longer dangerous. Until then, however, one avoids mentioning the deceased by name so as not to call attention to oneself as a possible victim. When someones dies, a diviner is called in to ascertain whose ghost has been responsible. When seriously ill, one sacrifices a pig to placate the ghost responsible.

Close relatives express their grief over someone’s death by cutting off a finger joint. This is clone by both sexes, and parents regularly amputate a finger joint on the death of a child. It is a widespread custom in the highlands and is practiced by the natives of the Wahgi Valley as well as by those west of Mt. Hagen.

Each clan possesses a sacred enclosure in which it grows a plant resembling an iris. This sacred plant is the focus of much of the ritual life of the natives. It can only be tended by young men between the ages of puberty and marriage. They must remain chaste or the plant will wither and die. Induction into the mysteries of the plant provides the occasion for initiating youths at puberty into premarital young manhood. By rubbing their chests with its leaves young men are able to have dreams which foretell the future. The plant is believed to have curative powers. If a bit of its root is eaten, it will ward off the avenging ghost of a slain enemy. It seems to be the most important fetish in the Wabaga region.

THE KUKUKUKU MOUNTAINS

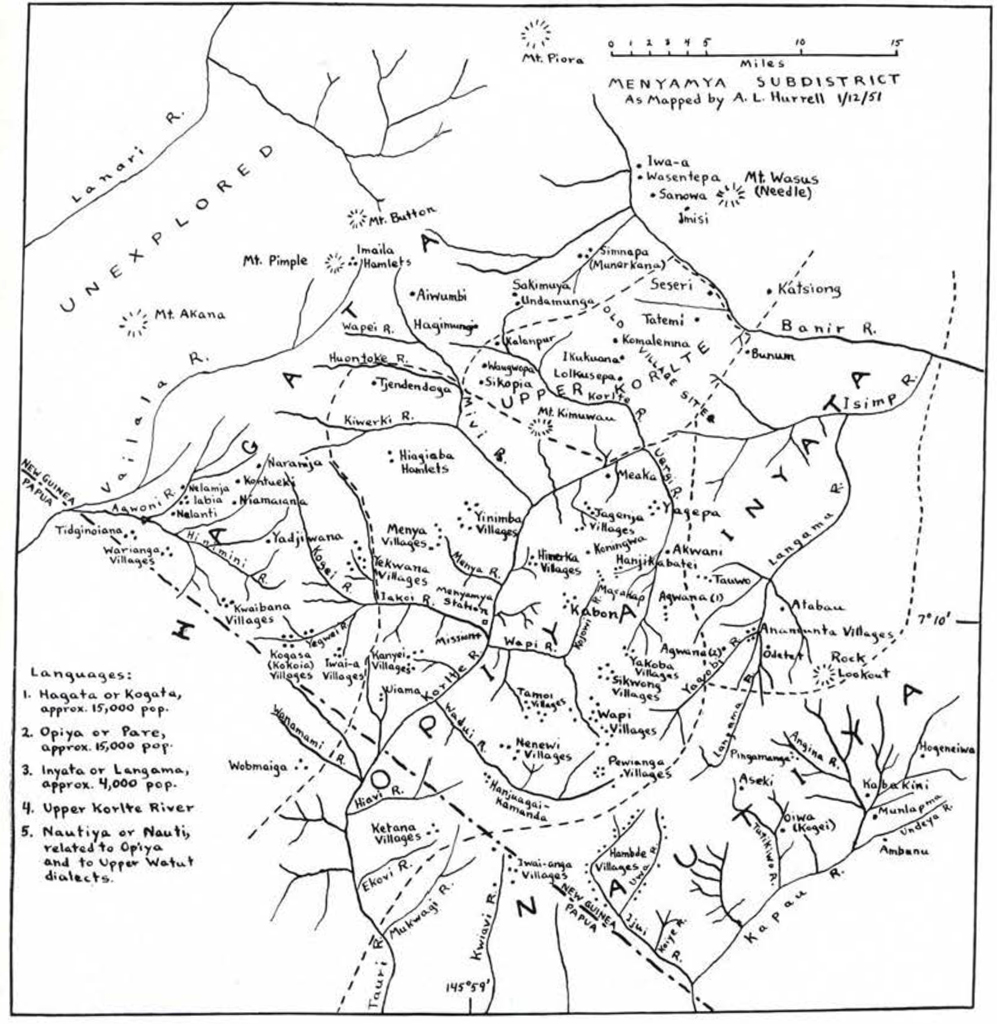

The southwestern corner of New Guinea’s Morobe district and the adjacent parts of Papua are inhabited by warlike natives known to their neighbors as the Kukukuku. It is a derogatory name which they dislike. Actually the Kukukuku people fall into three major groups: the Nautiya, Opiya, and Hagata; and two minor ones, the Inyata and Upper Korlte River people. The Opiya and Nautiya speak closely related dialects of the same language, but the Ilagata language is distinct.

Before the war two patrols penetrated the heart of Kukukuku country, but both were forced to withdraw after repeated attacks. A year ago a government post was opened at Menyamya in Opiya territory, the one spot in the entire area suitable for constructing a small air field. A mission station was established there as well, but it has yet to make converts. Since then, two Australian officers and a squad of twenty native police have been attempting to make contact with the 30,000 natives in the area and bring them gradually under government control. They are slowly making progress, but it will be several years under the most favorable of circumstances before these initial objectives can be satisfactorily accomplished.

The natives arc hostile to strangers, native and European alike, and arc reputed to make short work of them, given any kind of opportunity. The villages are continually fighting with one another as well, thereby making travel in the area as unsafe for Kukukukus as for outsiders. It was only through the courtesy of Mr. A. L. Hurrell, Assistant District Officer in charge at Menyamya, that I was able to visit two of the Opiya village groups. To do this required that Mr. Peter Moloney, Patrol Officer, and a line of ten police escort me for four clays. The hospitality and assistance which I received from these busy men was truly magnificent.

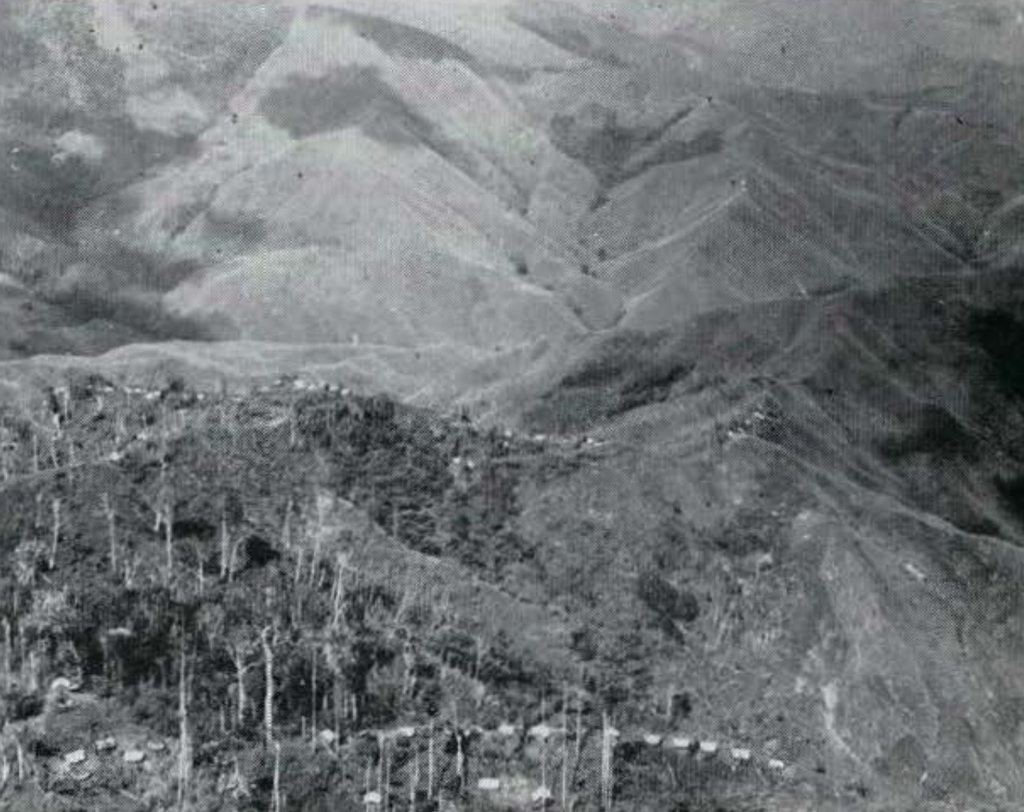

The Kukukuku country is extremely rugged. The mountains go up to between seven and eight thousand feet. There are numerous streams which have cut deep narrow valleys. Menyamya, which is in the Korlte River valley, has an elevation of about three thousand feet. The native villages are all up on the ridges between five and seven thousand feet at the headwaters of streams (Fig. 20). This arrangement gives them a water supply and at the same time provides a strategic location for defensive purposes. The valleys are no man’s land between village territories. All of the valleys are without trees, except along the stream banks. They are blanketed with kunai grass extending well up the mountain slopes. The tops of the mountains arc forested. Gardening is clone on the edge of the forest on steep slopes, with logs laid across the slopes to hold the soil.

Native diet is largely a vegetable one, the main crops being sweet potato, taro, sugar cane, and pandanus. Pigs are not numerous and no fowls are kept at all. The cassowary appears to be one of the chief sources of game.

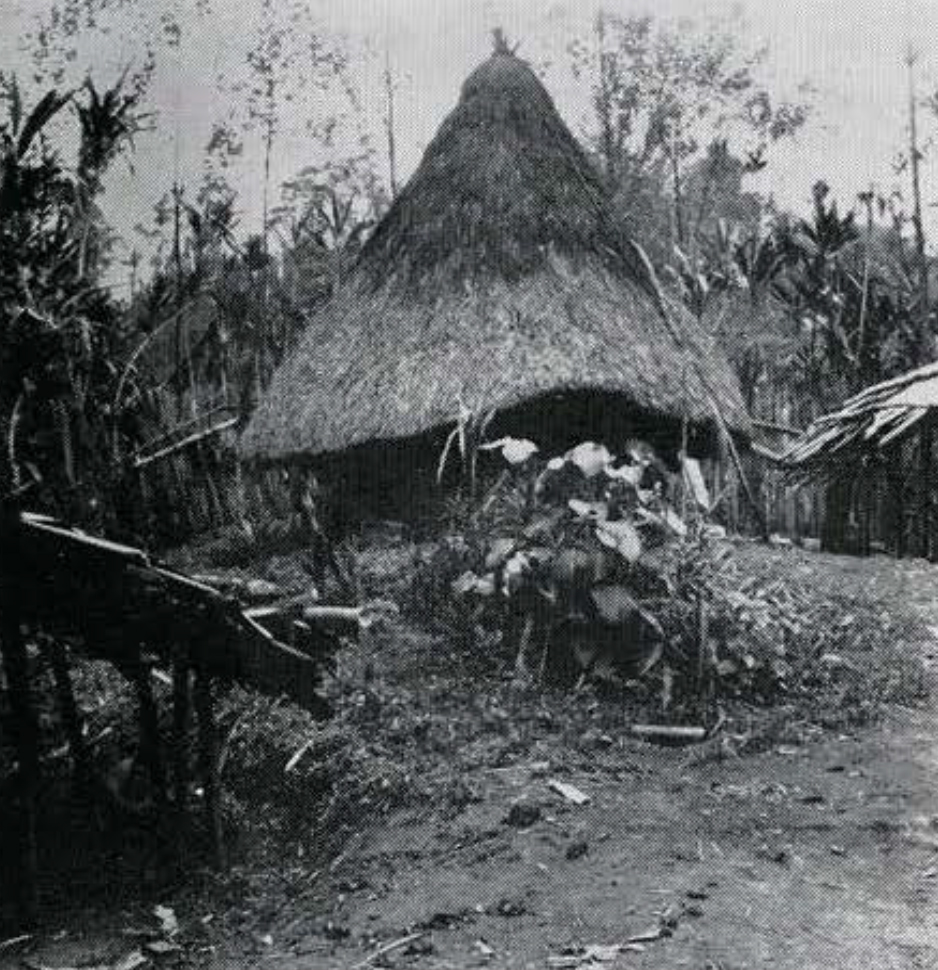

Each village consists of a group of scattered hamlets, anywhere from fifty to a hundred yards apart (Fig. 21). Each hamlet is occupied by the men of a patrilineal lineage together with their wives and children. Marriage within the lineage is prohibited. Within a hamlet each adult man has his own household. Since polygyny is common, his household is likely to contain quarters for several wives. One which I examined had two sleeping houses (Fig. 22) with two wives in each, a cook house for the women and a cook house for the male members of the family. Men’s houses are not a feature of Opiya hamlets, but are found regularly in Hagata villages.

A local group may consist of two or more villages clustered around the headwaters of the same stream or lying on either side of the same ridge. It customarily takes its name from the stream about which its villages are clustered. There is no social or political group of larger size. Political leadership is in the hands of “fight chiefs,” men who, regardless of age, have distinguished themselves in war.

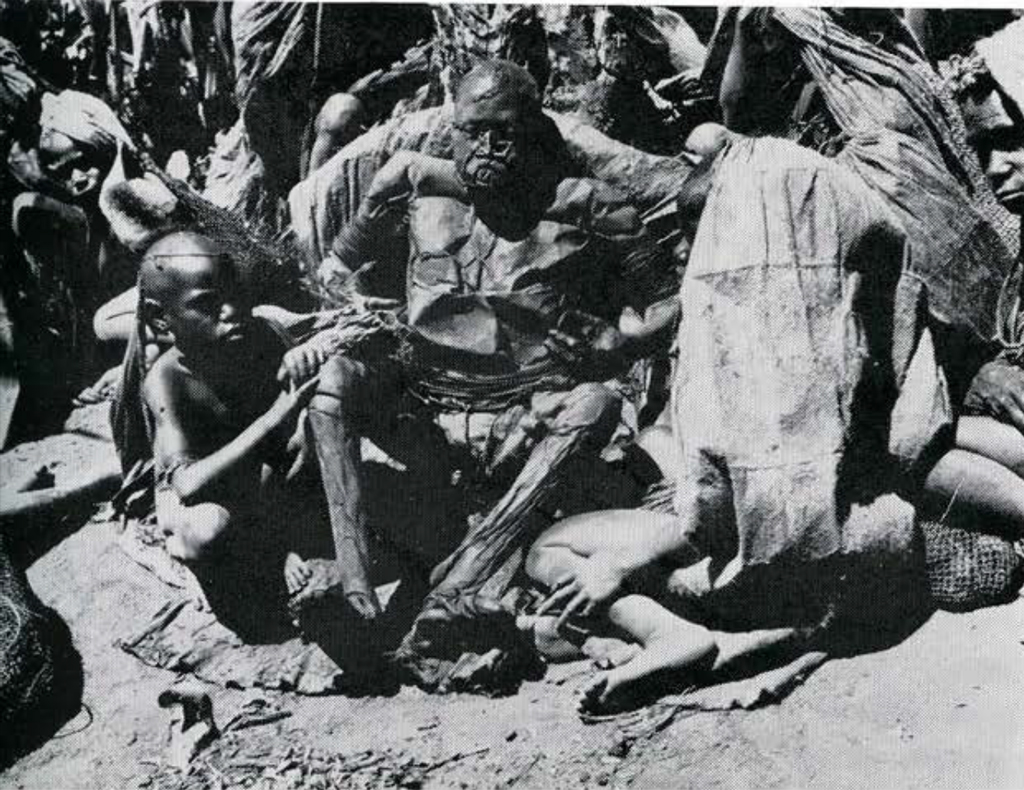

In warfare, the Opiya use an oval shield. The main weapon is the bow and arrow. Multipronged arrows are used for hunting, but single pronged arrows tipped with bamboo for fighting. The simple bow, made from a single piece of wood, is from three to four feet long. For in-fighting the favorite weapon is a stone-headed club. The stone heads take a variety of shapes. Discoidal and pineapple-shaped heads are common. The sneak raid is the usual tactic employed in warfare.

The Opiya are light skinned, short in stature and slight in build, though their musculature is usually well developed (Fig. 23). Men keep their heads shaved except for a circular tuft of thick, woolly hair on the crown. Every man carries a small cape made of barkcloth. The top of the cape is gathered on a loop of string which is pulled over the tuft of hair at the back of his head. Suspended in this manner, the narrow cape hangs straight clown his back to a little below the waist. A loin covering provides the only other item of dress other than ornaments.

To the accompaniment of bull-roarers, boys go through an initiation ceremony when about eight years of age. The nasal septum is pierced at this time. Following initiation, boys assume the dress of adult men. In addition to the items already described, this dress includes a pair of cassowary thigh bones, hung around the waist, and a bandolier of many strands of black and yellow beads going over the left shoulder and under the right arm. The usual nose ornament is a short yellow reed through the septum. The black spine of a cassowary feather is inserted in each end of the reed, its point curving back in the direction of the cheek bone. Less common as nose ornaments are bones or pairs of pig’s tusks.

The Hagata people bury their dead in an upright position. The Opiya, on the other hand, put the bodies of their dead in special smoke houses. The body is placed in a rack in a sitting position where it remains for six to eight months until it is thoroughly smoked. Before smoking, the head is opened and the brains removed. All body openings are stopped up. After a few clays of smoking the epidermis blisters and peels off. When the internal organs have liquified, the body is tapped through the anus and the liquid is drained off. As smoking progresses, fats drip from the body. They must not be allowed to touch the ground, and someone must be in constant attendance to prevent their doing so by wiping them off the body. When the smoking is finished and all traces of odor have left, the body weighs about twenty pounds (Fig. 24). A house like a large bird-cage is then erected on a post in the garden or pandanus grove, and the body is seated in the house (Fig. 25). The Opiya believe that the body in this manner protects the land from evil spirits. It remains in its cage until all but the bones has rotted away. The bones are then taken to a community ossuary on a mountain nearby.

CONCLUSION

Each of the four areas surveyed would greatly repay intensive ethnographic study. For the time being, the Kukukuku country must be ruled out as unsafe for any but a strongly armed party. There are groups related to the Nautiya in the Upper Watut Valley which are under control and which could be studied. Their life, however, has been affected by the proximity of the Wau and Bulolo gold mines.

The Western Highlands are ideal for study from almost every standpoint. They do not present a great deal of variety, however, and a few intensive studies in strategically selected areas would go a long way towards providing a good ethnographic picture of the region. If the Museum’s plans for study in New Guinea are of limited scope, this would be the place to work.

Adequate coverage of New Britain or the Massim will require ambitious plans for a long term program of study. Once organized, such a project would provide countless opportunities for study for a long time to come. Of the two, New Britain is the less known, the more varied, and the more colorful. It presents opportunities for every kind of ethnological interest. For purposes of long range study it is the most inviting of the places visited.

W. H. G.

1 I am indebted for help and hospitality to so many people-government officials, missionaries, plantation managers, traders, and natives-that it is impossible to make individual acknowledgment to them all in this paper. The kindness that I was invariably shown, the friendships that I made, all leave me profoundly grateful. ↪