Romantic tradition in the western world pictures primitive communities as exciting combinations of colorful dress, bizarre customs, and sinister rites. Anthropologists, who make it a business to study these communities, are used to finding their inhabitants normal human beings most of whose time is concerned with the daily requirements of making a living. Furthermore, they are dedicated to the job of showing how the seemingly bizarre and sinister are after all devoted to the accomplishment of mundane ends. Sorcery turns out to be important in law enforcement where police and jails are wanting; elaborate initiation rites at puberty serve to dramatize the seriousness of adult responsibilities; and mysterious secret societies turn out to be social or political clubs which operate very much like our own lodges and brotherhoods. Thus anthropologists find themselves in the role of debunkers of the romantic view of primitive man. The fact remains, however, that most societies have their colorful and dramatic moments, except where they have recently undertaken experiments in “puritanism.” It is one of the crosses which anthropologists must bear that they are likely to study societies precisely at the moment when they are in the throes of these experiments, and the color and drama that were uniquely their heritage have become a distorted memory while modern substitutes are not yet developed.

Image Number: 61821

Image Number: 61822

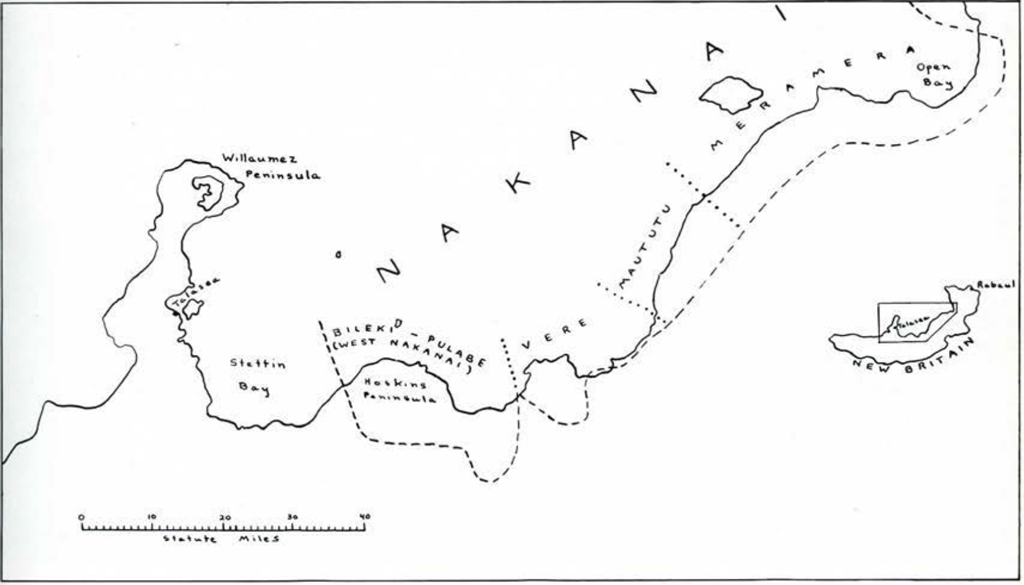

The region of the western Pacific known as Melanesia is one whose native inhabitants prior to European contact presented much of what to us westerners is most dramatic and colorful. It is an area, moreover, in which there are some communities which have yet to see a European, and others which have not yet learned to look clown with shame and embarrassment on that part of their heritage which gives them their individuality. An important part of a museum’s business is to be concerned with these very things which set people apart, which give to each community something distinctively its own, in which its members take special interest and pride. The University Museum has quite properly, therefore, a stake in Melanesia.

By way of doing something about it, the Museum and the Department of Anthropology sent me in 1951 to make a reconnaissance of several areas in Papua and New Guinea with a view to picking one for further study. In my report on the results of that survey (University Museum Bulletin, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1952), I suggested New Britain as the region in which I felt it would be most fruitful for the Museum to conduct a program of ethnographic research. It would not only accord with the Museum’s interests as a museum, study of New Britain could also help fill in a serious gap in our knowledge of the ethnography of Melanesia. Accordingly, I returned to New Britain in February of 1954 with several graduate students to make a six months’ study of the West Nakanai people on the central north coast of the island.1 The following account is based directly on our observations during this study. But it should be remembered that we have not yet had the opportunity properly to analyze our field data-a year or two’s job in itself-so that what is said here is necessarily by way of preliminary comment only.

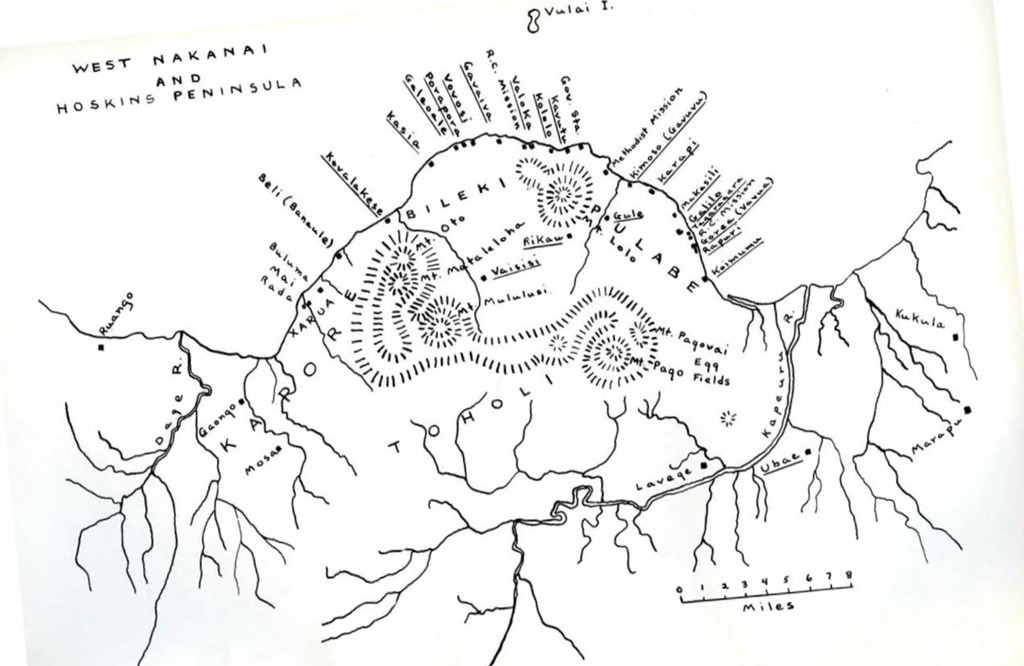

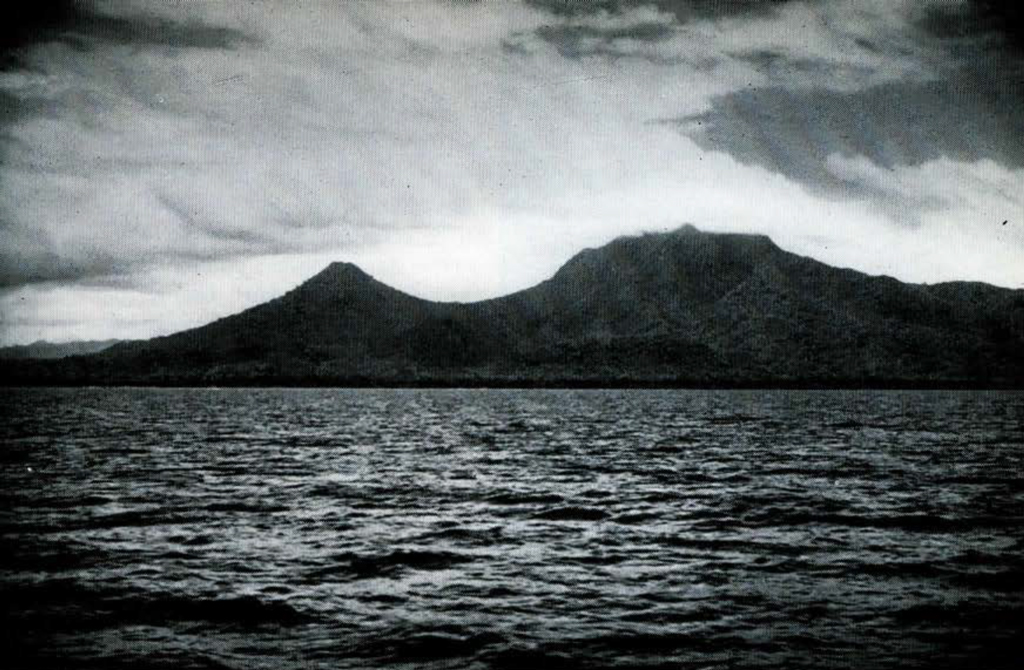

The Nakanai people occupy a one-hundred-mile stretch of coast between the Willaumez Peninsula and Open Bay. Along most of this coastline rugged mountains rise from the shore, leaving only a narrow strip of lowland. The area is actively volcanic. It is subject to a rainy season between the months of December and March, the rest of the year being dry. The Nakanai are divided into several major dialect groups which are very closely related, but whose extremes are not mutually intelligible. Numerically most important today is the West Nakanai group, inhabiting the Hoskins Peninsula. It was here that we worked, settling in the two nearby villages of Galilo and Rapuri.

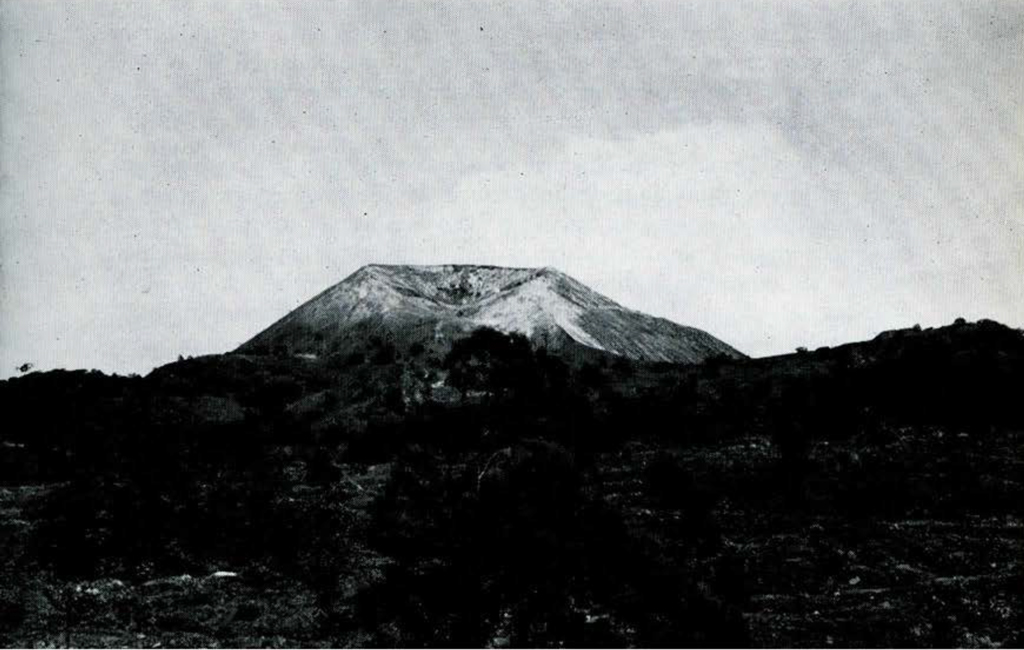

The Hoskins Peninsula is a semicircle of flat Janel bounded at the base by a chain of mountains and ridges. At one end of this chain is rugged Mt. Oto, while at the other is the active volcano, Mt. Pago, whose violent eruption in 1914 laid waste the entire peninsula and forced its people to abandon it for several years. At the apex of the peninsula the extinct Mt. Lolo raises its graceful, solitary cone. All but three of the twenty-two villages located here are near the beach. There are few water holes inland on the plain. Rain filters quickly through the porous volcanic soil and the underground drainage emerges in springs a few yards from the beach. To be close to water, therefore, most villages must be near the shore.

Image Number: 57311

Image Number: 242461

Each village consists of one or more hamlets. In former times the hamlets were separated by a few yards of bush, but now they tend to be consolidated in a single clearing, though retaining their separate social identities. Each hamlet contains several dwellings and a men’s house set around a little square, every inch of which is kept completely clear of all vegetation except for a shade tree or two. The edge of the square is planted with betel and coconut trees. Normally, there are large shade trees at one corner of the square under which is the hamlet’s feasting ground. In former times, the rectangular dwellings were built directly on the ground with frames wooden and bark walls and roofs. Nowadays houses for sleeping are raised on piles and thatched with nipa palm leaves, but the old style houses sometimes continue beside them as “cook houses” in which the older people still prefer to sleep. It is in the latter houses that all valuables are still kept and in which most indoor living takes place. On the dirt floor of these houses are as many stonelined hearths as there are women (other than small children) in the household. Whether young or old, married or single, each woman cooks at her hearth for herself and such of her relatives as she helps to feed from the produce of her gardens.

Back of each village is a tract of bush-dense secondary growth within which the villagers make their gardens. A strip of virgin forest separates one village tract from the next. An entire village, or several hamlets within one, will mark off an area in its gardening territory, starting one or two miles back in the bush. Within this each participating hamlet takes a strip and fences it. Each man clears his own plot within his hamlet’s strip and prepares the ground for planting. The woman who is his gardening partner plants it and looks after it from then on, harvesting the produce and cooking it. Since there is no way of storing food, the Nakanai are constantly clearing and planting new plots the year round, regardless of the season. A plot is planted only once and when harvested goes back to bush. In the course of time the garden strips move toward the coast until they come too close to the village, where, despite fencing, they are too easy of access to the village pigs. Then the community starts a new set of strips back in the bush and proceeds to work coastward again. After fifteen or twenty years it will return to the first garden site. While garden lands are not communal property, the people feel that since gardening involves only transient use of the land it is not a form of trespass on private property rights, though the owners must be consulted before clearing begins. In- deed, the owners are only too glad to have their land used, because this will keep it from going so far back into forest as to require a new primary clearing operation. Small bush, however thick, is easier to clear (whether the tools are of steel or of stone and shell) than is timber. Once cleared of forest, land acquires a value which can be maintained only by periodic use. Cultivated crops are numerous: taro (the staple), sweet potato, sugar cane, greens, yams, tapioca, cucumbers, tomatoes, pumpkins, beans, tobacco, and ornamental leaves worn by the women. Also planted are bananas, coconut, breadfruit, betel, and citrus.

Behind the garden lands is the virgin forest-tall trees whose deep shade inhibits the growth of underbrush. Here the men hunt for pig, cassowary, and small game. This too is the preserve of a pheasant-like bush-fowl whose meat and eggs are an important source of protein food in the local diet. These fowl lay their eggs in prodigious numbers in holes in the ground in a region of bare hot soil at the foot of Mt. Pago. The Nakanai regularly collect these eggs (which are twice the size of a hen’s egg) throughout the long dry season. Rights to the egg fields for gathering purposes have been the cause of much warfare between native com- munities in their vicinity. The eggs are gathered not only for immediate consumption but also for sale to communities too far away to exploit the fields directly. The Nakanai also keep domestic pigs and chickens. The only other domestic animal is the dog, which is used in hunting-as well as being eaten.

The sea provides the other major food-stuffs in the form of fish and shell-fish. Those communities close to the egg fields have relatively poor fishing grounds, as it works out, while those more removed have reefs close to their shores which provide sufficient quantities of fish. The big rivers at either encl of the peninsula are also important sources of fish.

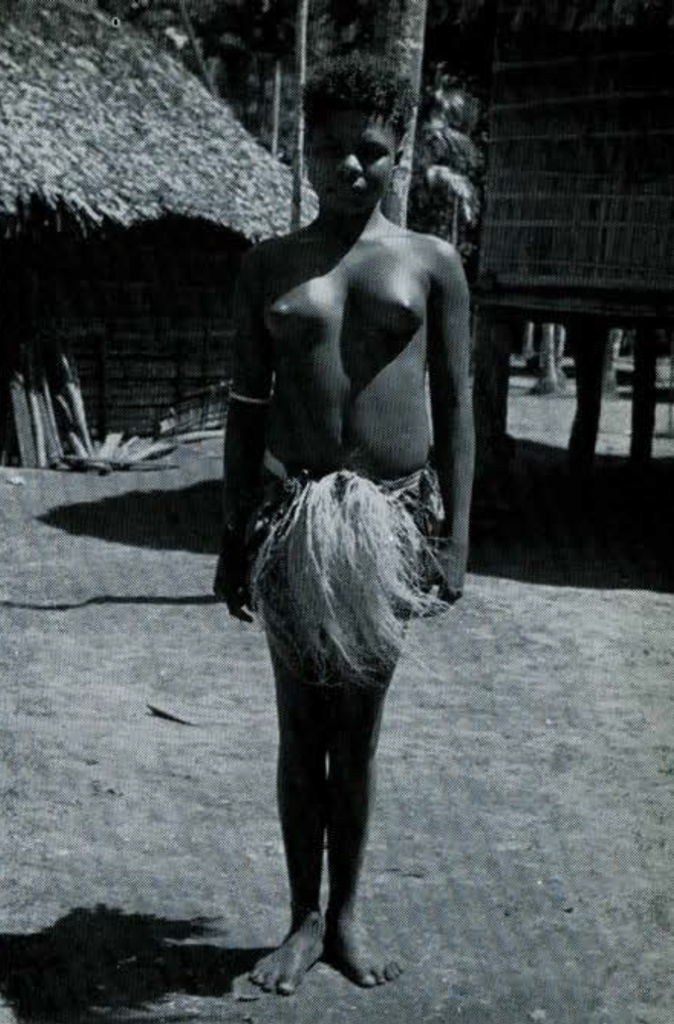

Ordinary dress for the Nakanai women consists of a belt with a short apron of leaves before and another behind. The leaves used are grown in the garden for the purpose. Some of them are heavily scented. Women coming in from their work in the gardens bring a fresh supply of leaves which they don after bathing. Until their recent adoption of the cloth wrap-around kilt or “laplap,” Nakanai men went naked except for barkcloth belts, but when dancing they wore a “grass” skirt made from fibers of the mangrove root. The first donning of this skirt by a first-born son is a ceremonial event. If not given to elaborate clothing, the Nakanai make up for it in adornment. Both sexes cut and stretch their earlobes and put turtle shell or reed rings on the loops. They pierce their nasal septa in which they wear a bar of tridachna shell or a set of turtle-shell rings. On the upper arm and around the leg just below the knee go braided armlets ornamented with small white shells. Over the bicep goes a set of turtle-shell rings. Braided circlets of purple-dyed fibers are worn around wrist and ankle, and men may wear broad fiber gantlets beaded with small shells on their wrists. On the head goes a crown-like frame of cured pandanus leaf tubing supporting a brilliant display of feathers which are family heirlooms. Needless to say, most of this splendor is for special occasions only.

Image Number: 60046

Tattooing has only recently come into vogue, but ornamental scarification of women’s backs is an old custom. Nor is the hair allowed to go as nature intended it. In former times, it was dyed black and worn in matted ringlets greased and sprinkled with powdered reel pigment. Nowadays it is trained by combing to stand up in a frizzly mop which is trimmed fairly short in modern New Guinea style and is alternately dyed black or peroxide orange depending on the individual’s fancy of the moment. As a result it requires close investigation to discover that the Nakanai are endowed with naturally brown to black hair which ranges from straight through wavy to very curly in form. Other physical characteristics include from medium to dark brown skin, an average stature for males of 5 ft. 6 inches and for females of 5 ft. 2 inches, large teeth with about 90 per cent incidence of shovel-shaped incisors (a Mongoloid trait), large palates, heavy jaws, often rugged brows, and muscular build. The people impressed us as hard-working and vigorous, especially considering the debilitating effects of universally chronic malaria and hook worm.

The Nakanai are divided into about forty clans. These clans are matrilineal, by which we mean that a person belongs to the same clan as his or her mother (not father). Every clan has associated with it a mountain or height; a body of fresh water, be it river, stream or spring; one or more animals or fish which it is tabu for its members to eat; several cultural or other objects whose origin is associated with the clan’s origin; and personal names of people and pigs. The Kevemuki clan, for example, which is currently one of the most important in West Nakanai, has the volcano Mt. Pago as its sacred mountain. The spring Kalea on its slopes is its sacred water, the chicken its tabu, and taro, fire, and the sun are its associated objects. Many clans share in the same mountain, spring, tabu, or objects. These clans are considered to be sub-clans of a single larger one. Thus Kevemuki has at least five sub-clans: Hahili, Kureko, Matapoo, Kalea, and Goau.

When someone sets out to clear virgin forest for a garden or to establish a new hamlet, the ground is thenceforth considered the property of his clan. If two men of different clans jointly establish a new hamlet, its ground is then the joint property of their two clans. Title to the property is administered by the matrilineal descendants of the founder or founders. Men do not normally take up residence in the hamlet associated with their clan, however, until after their fathers have died. Even then they may continue to reside in the hamlet of their father’s clan for a variety of reasons. Each hamlet, therefore, tends to consist of a few older men of the clan or clans which own its ground, their sons, those of their sisters’ sons whose fathers have died, and perhaps a dead brother’s son who has decided to stay on rather than return to his own clan’s hamlet. Each hamlet is composed, therefore, of a group of fairly closely related men with their wives and children. Their leader is ideally the eldest resident man who belongs to the owning clan, but his position is influenced by his wealth and his reputation as a giver of feasts.

Several such hamlets make up a community or village whose members are normally at peace with each other but which as a unit is chronically hostile to the members of other communities (prior to the white man’s peace). Peaceful relations between communities were limited to visits between fellow clansmen and to festival and ceremonial occasions. The two most important foci of festival and ceremonial were and still are the masked representation of spirits-stretching over several months of the dry season (though not necessarily every year)-and the long cycle of feasting and dancing in honor of the dead-taking several years to reach its climax. Masked representation of the spirits is a community undertaking, while memorial feasts are privately promoted by individuals who stand to gain great prestige thereby. Of the two types of festival, that having to do with the dead stands first in drama and energy consumed. There is no festival of greater importance or interest to the Nakanai. This is why I have chosen to take it as the subject of this brief report.

When a man dies, everyone in the community assembles at his house. People from neighboring communities come also, the women in the lead and the men following, all singing a dirge. They sing all through the night. The immediate relatives of the deceased make handsome gifts to the chief representative of each mourning delegation from another community, normally the deceased’s closest kinsman among them, who must then kill pigs and make a funeral feast on his return home. They bury the dead man at noon on the clay following death-they have to wait until the ground has warmed up in the heat of the clay. The man is buried in the floor of his house in a shallow grave with his head left above ground. (Nowadays bodies are buried in cemeteries.) His head is oriented toward the sacred mountain of his clan, from which his spirit came when he was born and to which it returns now that he is dead. His head is exposed so that his family may continue to behold his face. They are concerned about his feeling cold in the ground and build fires over him to keep him warm. This may continue for a few days only or until such time as the dead man’s face has completely decomposed, and then the body is completely buried.

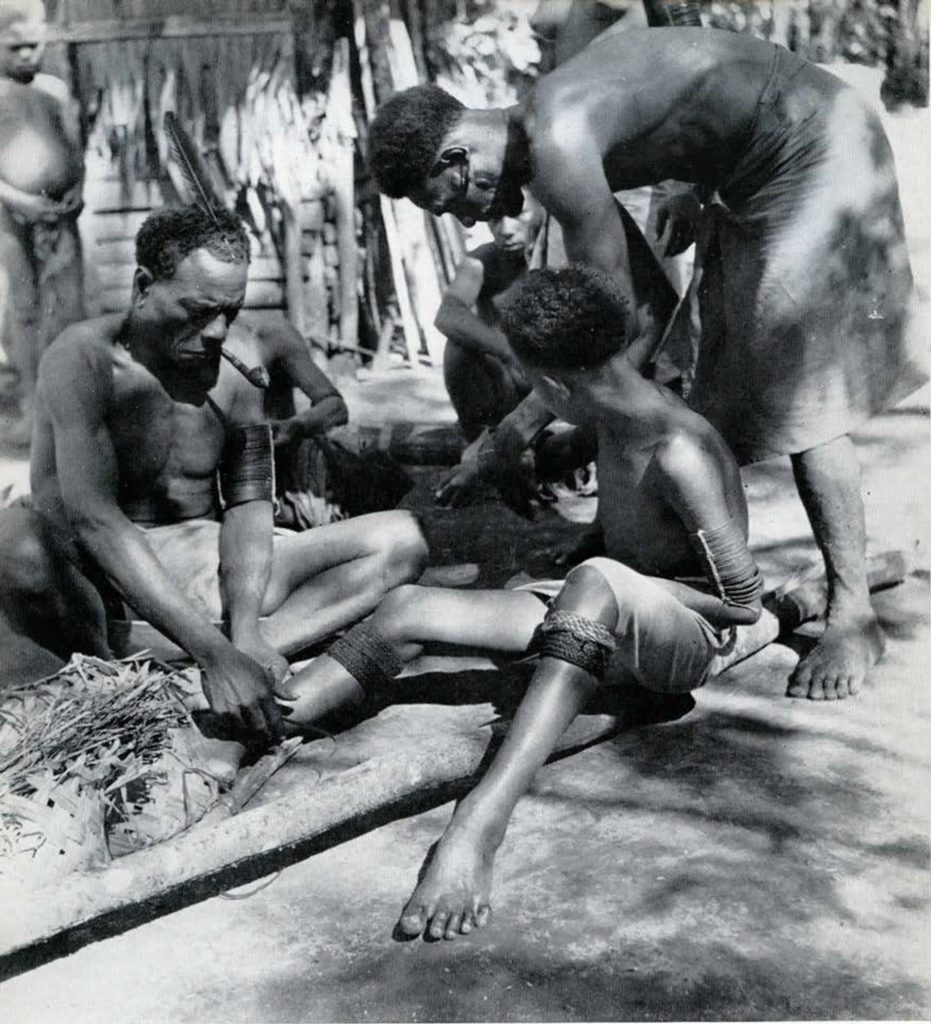

Meantime, the dead man’s wife and sister are incarcerated in a small closet which is partitioned off in the house for the purpose-normally the house of a relative of the deceased. Here they remain in strict mourning for from one to two months, being allowed out only twice a day to perform their natural functions. During this time they may not bathe, must wear special clothes, including heavy wrappings of vines on the legs so that they can walk only in a waddle, and must refrain from eating pork, fish, or taro and from smoking tobacco or chewing betel. When the dead man’s clan mates decide that they have mourned enough, they break down the partition and formally release the women. The widow may now cut her hair and do limited work, but she must still refrain from gardening for about two years. She is not free to marry again during this period, but must wait until her former husband’s clan mates release her from all mourning. If she violates the mourning regulations they are likely to try to kill her.2

A few months after the body has been fully buried, a close male relative of the deceased (brother, son, or nephew) secretly exhumes it. He removes the humerus or upper arm bone, reburying the rest of the remains. He informs the other immediate relatives of his action and, if it appears that they have the means to undertake it, they decide to go ahead with the memorial festival. The man who took the arm bone paints it red, wraps it in red bark cloth, then wraps this bundle in old pandanus matting so that it will resemble many other bundles containing items of family wealth and hangs it with them from the ridge-pole of his house. Nothing is said to the community at all about his intentions.

He and his near relatives who are in on the secret set out to accumulate pigs. They buy them where they can and breed them to raise as many pigs as possible. They begin to give the young pigs to others in the village to look after. By this time, the elders in the community are aware that something is up. One of them discreetly inquires of a near kinsman of the deceased what is the meaning of the pig-breeding activities. The feast-maker then publicly announces that he has taken the dead man’s arm bone and intends making a memorial festival.

Image Number: 57312

This announcement is immediately followed by the ceremony of “hanging the bone.” The feast-maker places the bone on a circular wooden tray which he suspends from the ridge-pole of the men’s house in his hamlet. He hangs a set of ankle rattles, such as are worn in dancing, from the tray, so that any vibration of the men’s house will cause them to make a noise. He kills two or three pigs and distributes meat to the several hamlets of his own village and to those of neighboring villages (how many depending on the number of pigs he feels he can afford to kill). On this occasion other persons in the village who cannot afford to make a memorial festival on their own come forward with the arm bones of their dead. They add their meager resources to those of the feast-maker in return for riding on his coat-tails. All noise and clatter in the vicinity of the men’s house is now strictly tabu. Children may not cry, people shout, or women noisily clump their loads of fire-wood. No stones may be thrown at or near the house. Violation of the tabu is punished by the spirit of the dead man acting through a sorcerer hired for the purpose. These tabus are in force only for a few clays, after which there is a second feast for “taking down the bone,” though the bone is in practice left to hang in the men’s house until the final memorial celebration. This second feast is bigger than the first one and all the men of the village take part in cooperative drives with nets for wild pigs. When they have caught several, the feast-maker kills two or three of his domestic pigs to add to the total. The night after this feast, the feast-maker takes his family’s slit gong (hollowed log drum) and places it in the middle of the hamlet square just in front of the men’s house. This is known as “placing the gong,” and formally serves notice to all neighboring communities that they will be welcome to come here and dance.

The feast-maker thus maintains open-house for one or two years. When visiting groups of dancers come to dance to the gong he must provide them with tobacco and betel. If they stage an all-night dance around some formal theme, he must kill a small pig for them and provide them with food. These “theme-dances” require that all performers wear a particular type of ornament or call for the women of the host’s hamlet to attack the dancing delegation of men with a particular weapon: water, sand, mud, or fire. Such attacks may end with an orgy in the bush. The visitors always name the theme. The style of dancing done on these occasions is not an animated one. A man in the dancing group sits astride the gong and beats it with the butt end of a flexible rod made from a heavy vine. Rhythms are varied but not complicated. The dancers mill slowly around the gong singing and moving their feet in a shuffling heel-and-toe step. The songs are short and are sung over and over again. In theme-dancing one song will be used for the entire night. Other hamlets from the feast-maker’s village may enter into a dancing contest with a visiting delegation. Each group dances around a gong at either end of the hamlet square, singing its own song. Both groups keep going at the same time until one is too tired to continue further. Dances continue to be held around the gong until the feast-maker is ready to make the final grand festival. As the time approaches, the dances are more frequent so that dancing becomes almost a nightly affair for a month or two before the big day.

Meantime, the near relatives of the deceased continue to accumulate pigs, distributing the shoats to the other members of the community to look after. Ideally, on the great feast day every household head in the village should have a pig to kill. As the time approaches, the men go out and clear new garden plots which their wives and sisters plant. When these gardens are ready to harvest, the feast-maker announces the time for screening the hamlet’s feasting ground. Behind this screen the men will rehearse their dances for the coming festival. No adult women are supposed to go within the screened area nor are first-born sons who have not yet been initiated into the dance. What goes on within it, however, is perfectly visible from the outside, the screen of coconut fronds being a no-trespass sign rather than an effective physical barrier. Screening the feasting ground is a formal act. On this occasion the feast-maker kills several pigs and all the men of the community have a small feast within the screened area. Cuts of pork are also lashed to carrying poles and distributed to as many other West Nakanai villages as the feast-maker feels he can afford. The present of pork informs these villages that they are invited to attend the great festival and to take part in its dancing. The present also provides meat for the feast of screening the feasting ground for dance rehearsals in these villages.

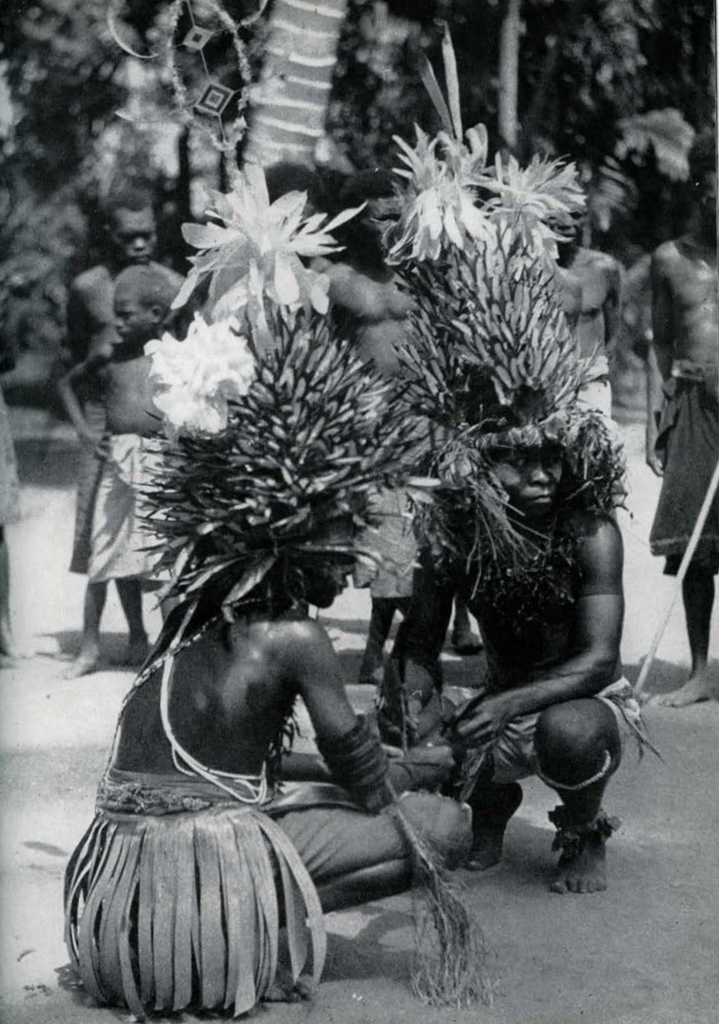

Every day the men of the host and guest villages meet in their respective feasting grounds to rehearse for the coming dancing. Unlike the previous dancing, the dances performed on the day of the big festival comprise a series of patterned movements executed in formation. They call for a double row of dancers. Those who perform as partners on the festival day thenceforth stand in a special relationship and can no longer address or refer to each other by name without paying a fine. The dancers go through various movements somewhat analogous to those in our own reels. There is considerable movement; feet stamp the ground in a variety of steps, noise of the stamping accentuated by ankle rattles. Rehearsal of these dances is accompanied by buying and selling of the rights to perform them. Such rights arc privately owned. Whenever a dance is performed, its owner must kill a pig to reaffirm his possession of the copyright.

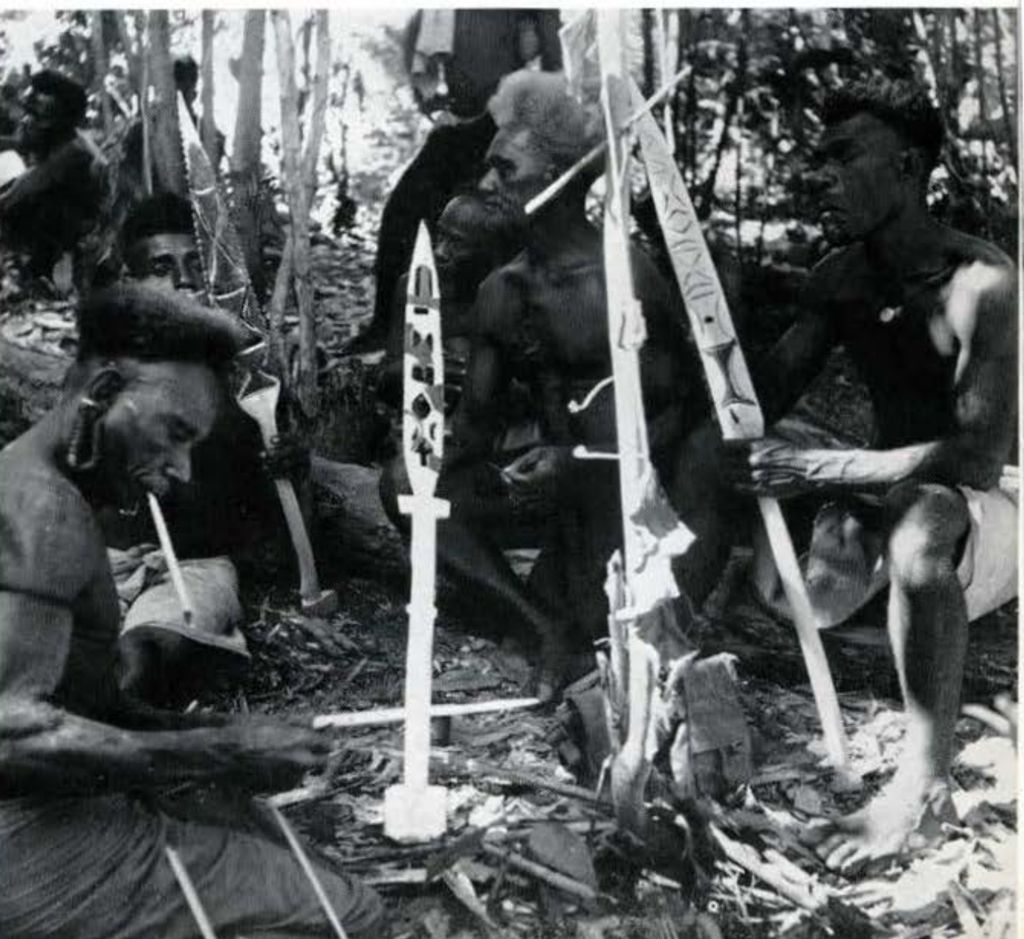

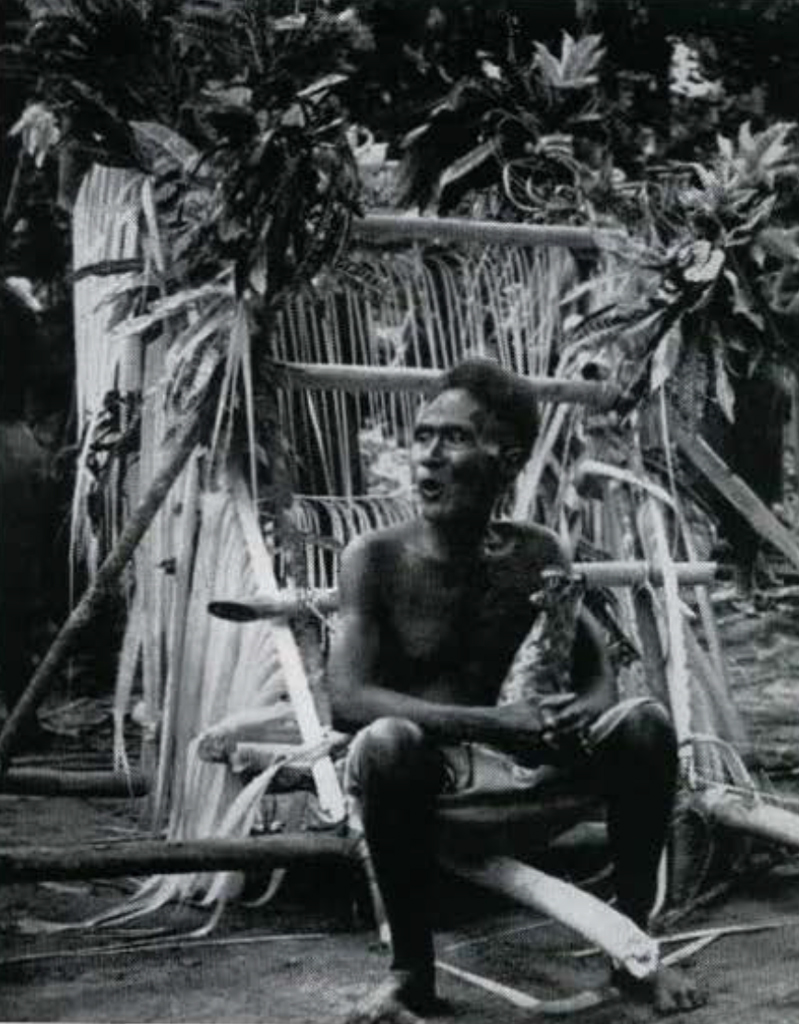

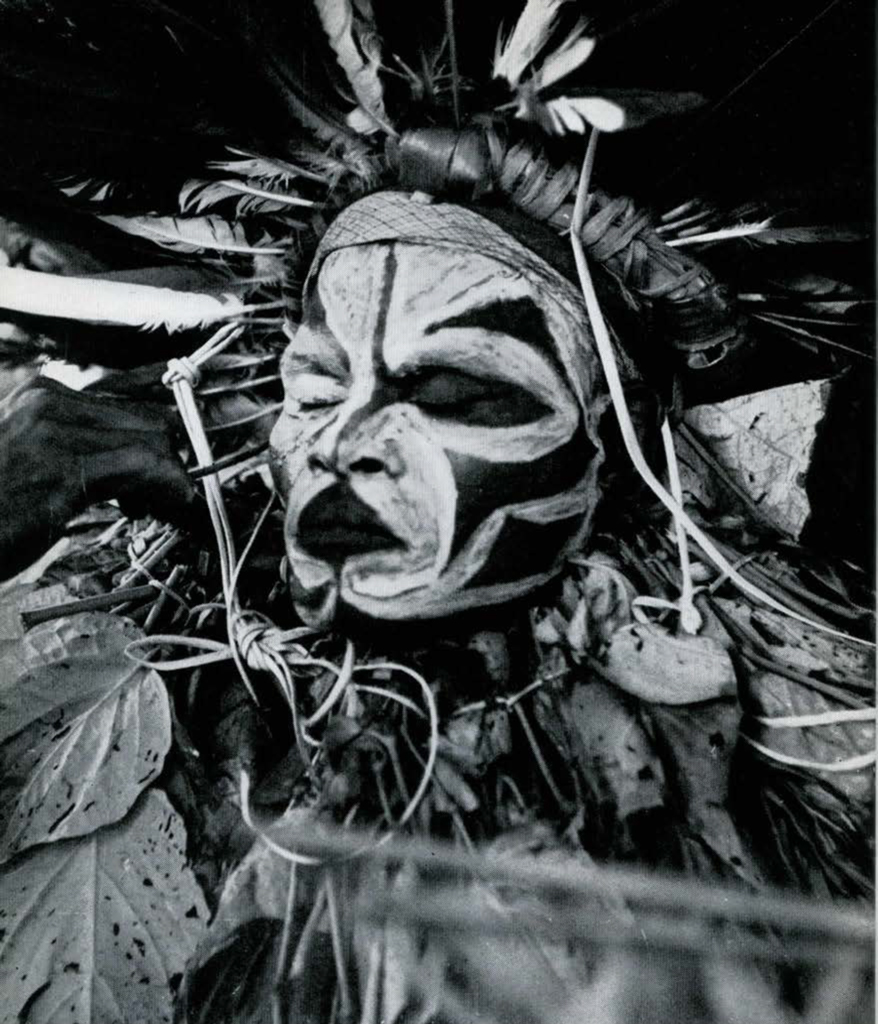

Men also start preparing the paraphernalia which the dancers will wear. Most of this work they do in the bush out of sight of women and children. The chief job is carving and painting the crocodiles, snakes, and lizards which will be manipulated by solo performers during the festival. Their relatives by marriage carry them on litters. A solo performer stands braced on the litter’s platform while his carriers heave it up and down. His face is elaborately painted. and he wears the fullest of ceremonial regalia. All the time he is carried, his eyes are glued shut so that he cannot see. In this blind and tossed condition, he performs his act, in the course of which he is paraded around the village area for five to ten minutes.

There is a wide variety of these solo acts-all of them, again, owned under private copyright. A common type of act is one in which a carved wooden crocodile, lizard, shark, dog, or pig is mounted on a track or trolley. It is rigged so that the performer manipulates lines which make the carved animal move forward and appear to bite his face and then retreat from him again. Instead of this, a performance may hold an elaborately carved wooden “pillow” across his shoulders behind his head. Another stunt is to appear to cat some inedible thing such as raw taro, or a human bone. Still other stunts call for having a fire burning on the performers lap, a spear seemingly run through his middle, snakes emerging from his mouth. Again, the performer may exhibit stalk-like protruding eyes or a greatly elongated tongue, or he may dress as a woman and carry a wooden doll-baby.

Prior to all of these acts, the performer must abstain from food and water for several days. He may eat and drink only enough to sustain life, and this only providing appropriate spells have been made first. The reason behind it all is love magic. Every stunt performed carries with it a potent love charm which is designed to make the performer irresistible to women. If he eats or drinks, he “cools” the charm and makes it impotent. The violent tossing he receives on the litter following his fast often results in physical collapse. Solo performing is a genuine ordeal.

The rehearsal period lasts for about two or even three weeks. The feast-maker ends it by killing a few more pigs and making another small feast. He sends cuts to all the villages to which pork was sent earlier, informing them that on the fourth day thereafter the festival will begin. One of the great concerns of the feast-maker is that there should be no rain on the festival clay. He hires rain-magicians, therefore, to keep rain away, and foil the attempts of any jealous rival to spoil the festival by magically causing a downpour. When the rehearsal period ends, the women break clown the screen around the feasting ground and rush in. First-born sons who have reached the age to be initiated into the dance go through a little ceremony of having the dancing skirt put on them at this time. They are then put in a line of dancers to follow as best they can. Their mothers, aunts, and sisters beat the ground at their feet with mats and throw food and wealth to the crowd in joy at the boys’ initiation.

The festival itself lasts for three days. It is opened with a dance by the boys and girls of the feast-maker’s village. A men’s dance belonging to the feast-maker or his family follows. Visiting delegations from other villages then present dances. The morning of the second day begins with solo performances. In each the arm bones to be honored, elaborately wrapped in ceremonial bindings, are carried by young kinsmen (occasionally women) of the dead as they are being tossed on litters. Also tossed on litters or carried on the shoulders of relatives are first-born sons who received their dancing skirt at the close of the rehearsal period. These appearances are followed by dancing on the ground. The third day is a repetition of the second, with the more spectacular acts reserved for this time. The host village performs the last number to close the dancing. The feast-maker has tile pigs (from forty to fitty in number) killed on the third day. The division of food to take home winds up the affair on the third afternoon, though informal festivities continue through the night and for several nights thereafter.

Image Number: 57313

The atmosphere on these three days is one of intense excitement. The dancers and solo performers get ready for their acts in the bush just off the village square. The women of the village dance in the square just in front of where they will emerge. Then with much shouting and chanting they come out surrounded by friends, some beating hour-glass drums, and led by one or two men with brightly painted shields and long wooden spears. They rush about beating their legs with the shields and thrusting at shadow enemies with the spears. Running about the fringes there may be a woman with spear and toy shield lampooning the men. Clowning, regularly done by women, usually enters into the performance somewhere. All the spectators follow the solo performer’s tossing litter about the village or throng around the rows of dancers so as scarcely to leave them room to perform. Sweat and paint stream clown the dancers’ bodies, turning to mud in the swirling dust. They wear fixed expressions-their gaze turned inward-as they struggle to call upon the last ounce of reserve to overcome their starvation and thirst and last out the dance.

After the festival, the feast-maker kills a pig to pay for “drilling the bone.” The dead man’s arm bone is drilled so that it can be mounted on the butt end of a spear. Everywhere men now go about their work with caution, and visiting other villages stops, for the spear with the attached bone must shed blood. To this end, the feast-maker presents the spear to one of the foremost warriors of his village. Under his leadership, a raid is organized. Raids against other villages continue until the spear takes a life. The warrior receives a pig, spears, and gold-lip shells in payment from the feast-maker, who takes back the spear with the bone. It will be used subsequently in fighting as an especially deadly weapon, but no further ceremonies attach to it.

There is no festival of greater importance or interest to the Nakanai than this one. The dancing and solo performances provide a tremendous spectacle. It absorbs the attention of the Nakanai as the World Series of baseball absorbs ours. But what this pageant means otherwise is not so easy to say. Presumably there have been beliefs about death, the life thereafter, and the relation of the living to the dead, all of which provided justifying reasons for taking the arm bone of the dead man, honoring it in some way, and finally blooding it on a spear. But what these beliefs are or were our informants either could not or would not say. Their stock answer was simply that it is something that has come down from their grandfathers. However frustrating this may be to inquiring anthropologists, the fact remains that there is little more that most of us could say about the reasons for doing much of what we do at Hallowe’en or Christmas. We have to have festival occasions, and these occasions must follow prescribed patterns if we are to enjoy comparing the way this year’s festival was put on as compared with last year’s. In this regard, the Nakanai are quite like ourselves. Their memorial festivals, moreover, not only honor important men who have died, but are the means by which the living prove themselves to be important as well.

Image Number: 57314

Successfully to make a great memorial feast is to establish one’s reputation through all of Nakanai as a leader among men. A leader must continue to promote such feasts when his kinsmen die in order to maintain his position. Memorial feasts, therefore, are an integral part of the social processes by which men gain public stature, and establish their right to represent their community to the outside world and speak with authority in it. There is no higher praise than to be called “foundation of the slit-gong,” which we may loosely translate as the “source of celebration.” The successful feast-maker, therefore, in honoring his dead, performs the most respected of public services. What, for reasons no longer remembered, started out as rites in honor of the dead have, in the course of time, been transposed into an expensive public entertainment which few men have the energy and resources to promote successfully and which has therefore become a means for gaining social recognition and influence. Private sentiment for the dead is felt, of course, by the immediate kin, but death also serves as the established excuse for a public celebration whose meaning must be found in the pattern of life in the larger Nakanai community.

Striking evidence for this conclusion is provided by the fact that the memorial celebration and events specifically leading up to it are the least modified of all Nakanai customs relating to death. Formal mourning has almost completely disappeared-only the food tabus continue to be observed. Burial is now in a cemetery instead of in the house. The arm bone itself is no longer taken, but some object intimately associated with the dead (e.g., cane, toy, leaf apron) has been substituted. Attaching the bone to a spear and shedding blood with it has, of course, gone out under European rule. What remains is the great celebration, the pageantry, the economic effort, the prestige-all of which show how important to the Nakanai are the social aspects of their mortuary customs.

1 Accompanying me were Miss M. A. Chowning, Mr. D. R. Swindler, and Mr. and Mrs. C. A. Valentine. The expedition was aided financially by the Department of Anthropology of the University of Pennsylvania, the American Philosophical Society, and the Tri-Institutional Pacific Program (TRIPP, a research program jointly administered by the Bishop Museum, University of Hawaii, and Yale University). Mr. Swindler’s work was helped by a pre-doctoral fellowship from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, and Mr. Valentine’s by a Fulbright Scholarship to the Australian National University. Our work was greatly helped by the extraordinary courtesies extended us by the Administrator of Papua mid New Guinea and his staff, which included synchronizing a botanical survey of the Nakanai area by the Department of Forests with our study. We are especially grateful to Assistant District Officer Michael Foley and Medical Administrator A. V. Bell, both of Talasea, and in Nakanai to Patrol

Officer and Mrs. Ernest Sharp, Miss Cynthia Smith of the Malalia Mission, Father W . Berger and the Sisters of the Valoka Mission, and Mr. Frank Maynard of Matavulu Plantation for their many kindnesses and cordial hospitality. ↪

2 Men are subject to similar mourning restrictions on the death of a wife, but for a shorter period of time. ↪