Image Number: 56-3-79

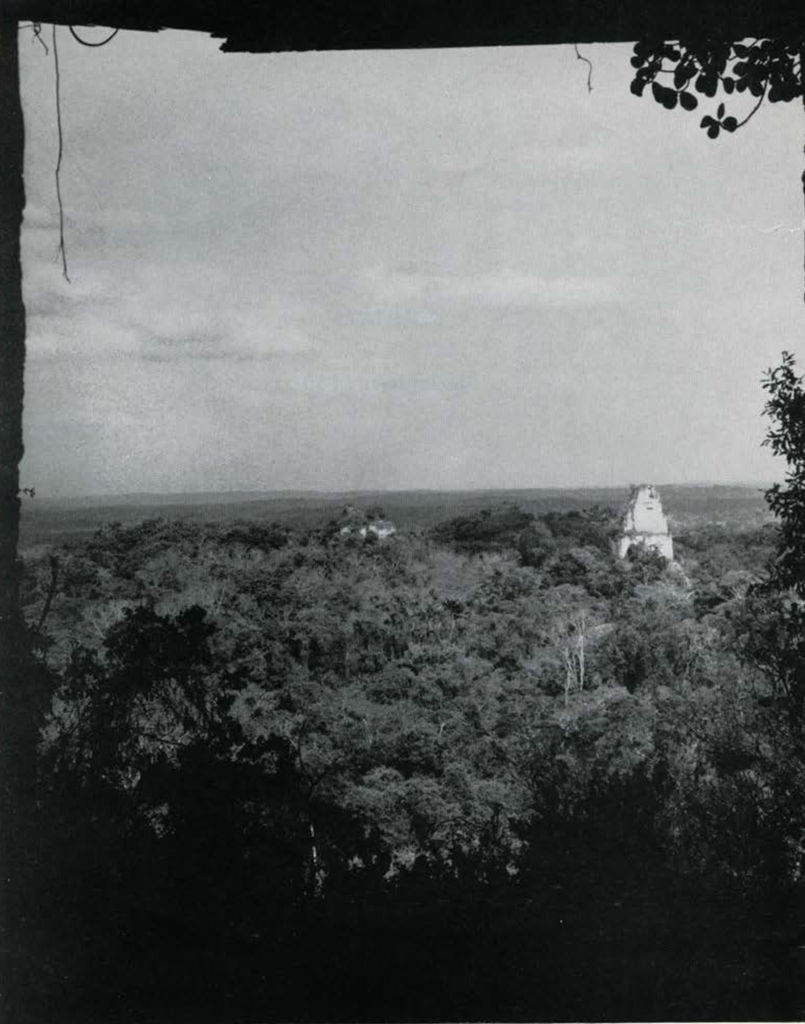

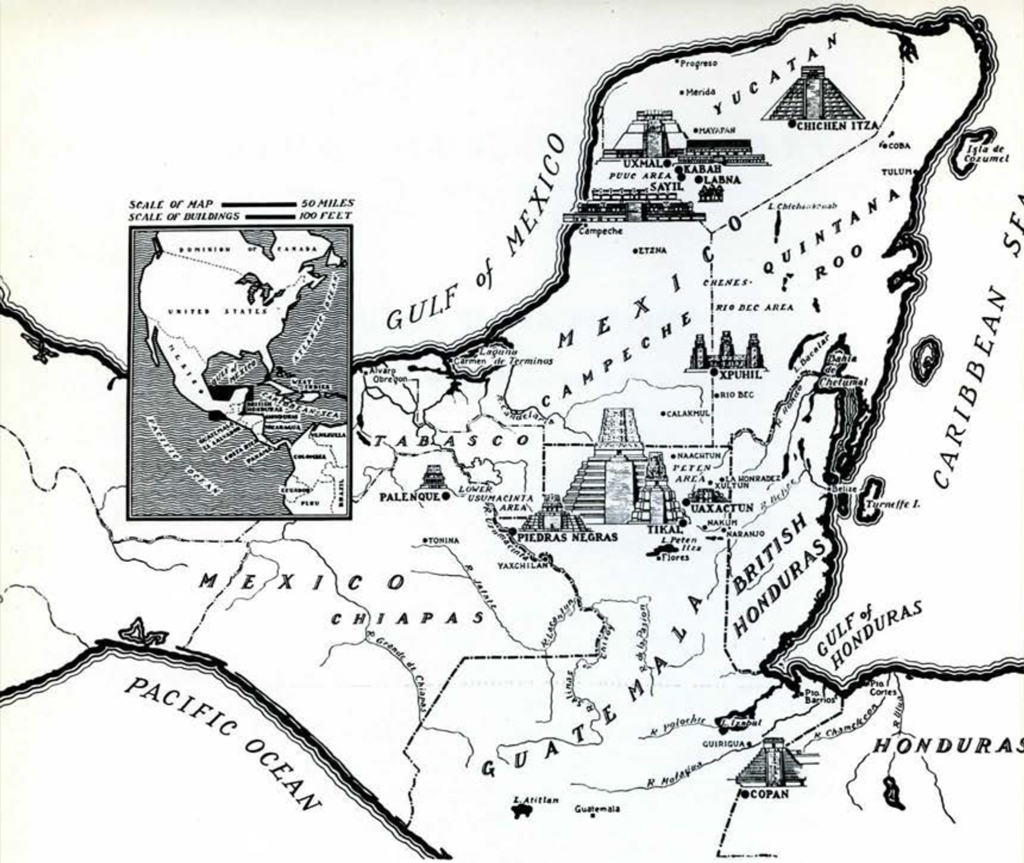

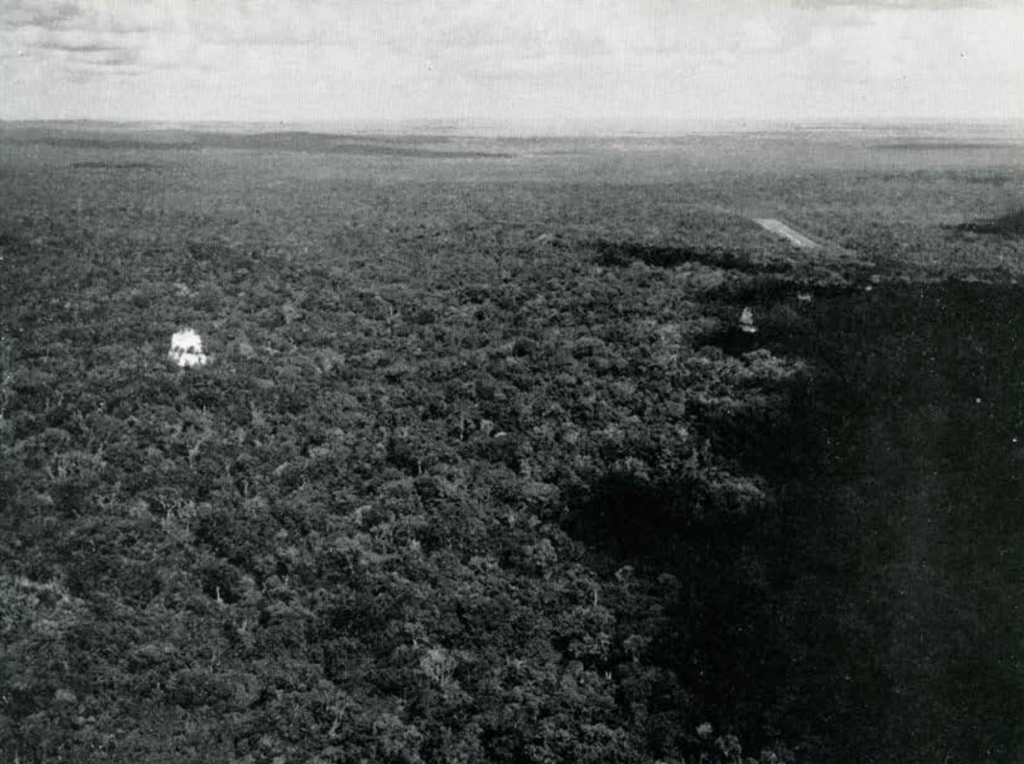

When I came to the University Museum in 1947, Percy Madeira spoke to me of his hope that some day the Museum might undertake the exploration of Tikal, the largest, and probably the oldest, of all the great Classic Maya cities in Middle America. At that time Tikal was a “lost” city buried in the dense tropical jungles of northern lowland Guatemala. It was completely covered by the tropical forest in 1937 when Samuel B. Eckert of our Board of Managers photographed it from the air. It was then feasible for Mr. and Mrs. Eckert to see it on the ground because an air-strip had been opened some 15 miles (24 km.) away for the chewing-gum industry. Though silent and deserted it had been known for a hundred years and preliminary surface explorations by archaeologists had been conducted on several occasions. An adequate investigation here had been prevented by inaccessibility and lack of a year-round water supply. The modern aeroplane changes the picture.

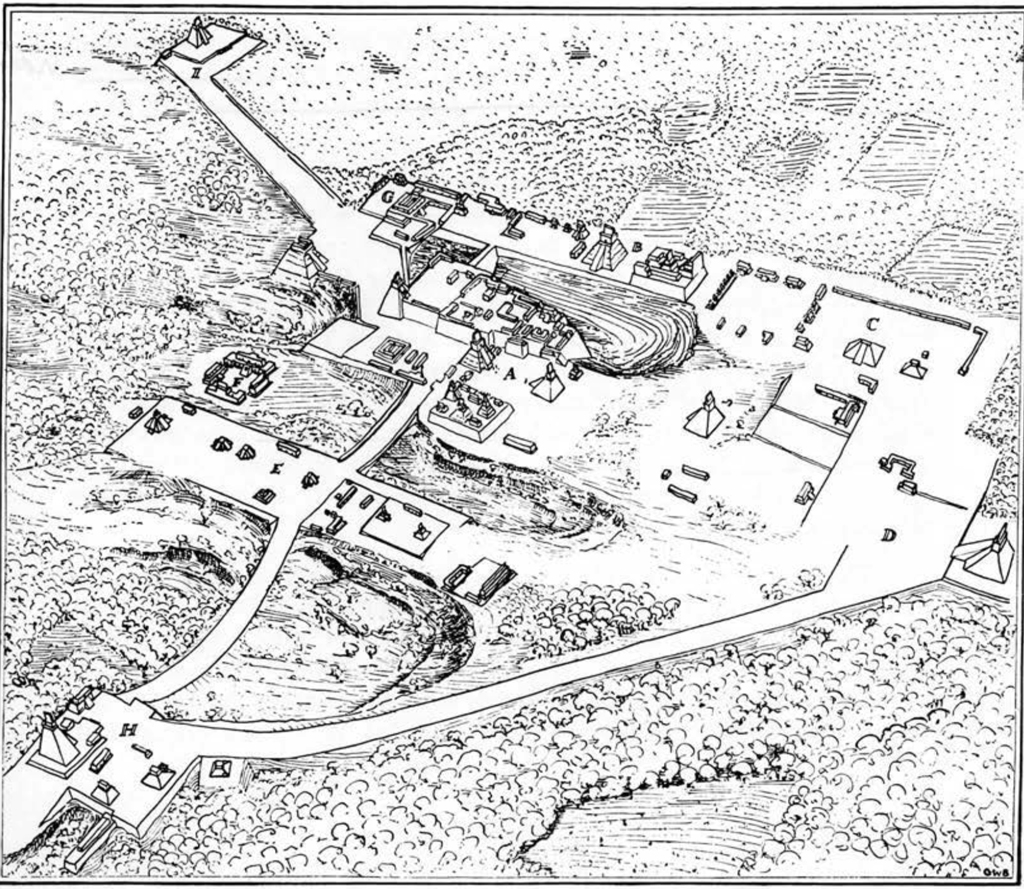

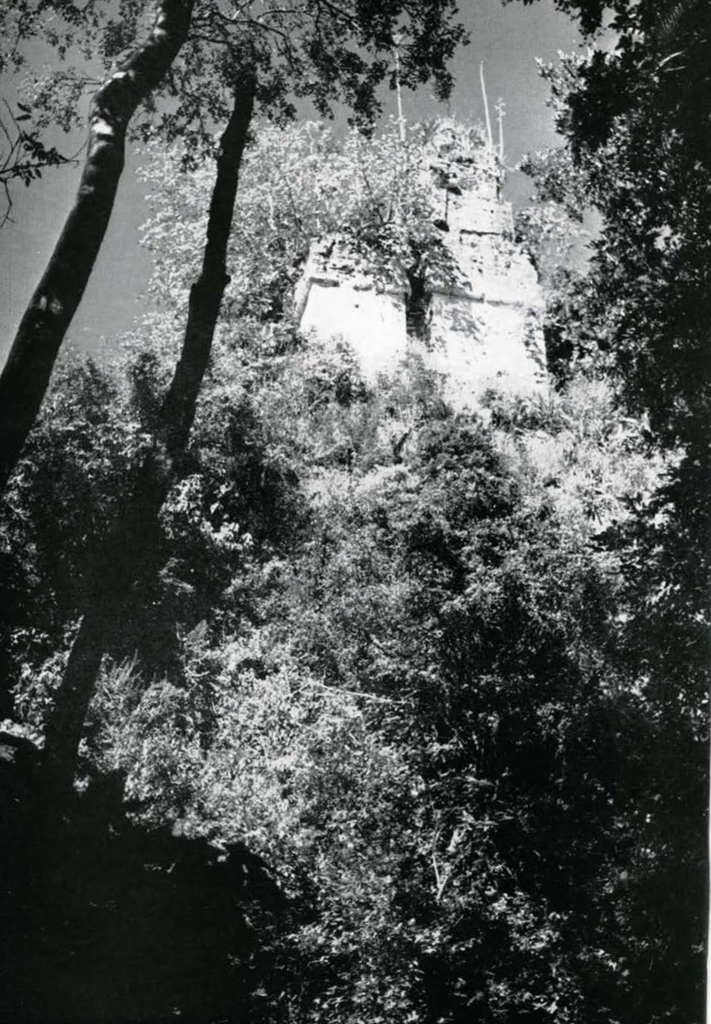

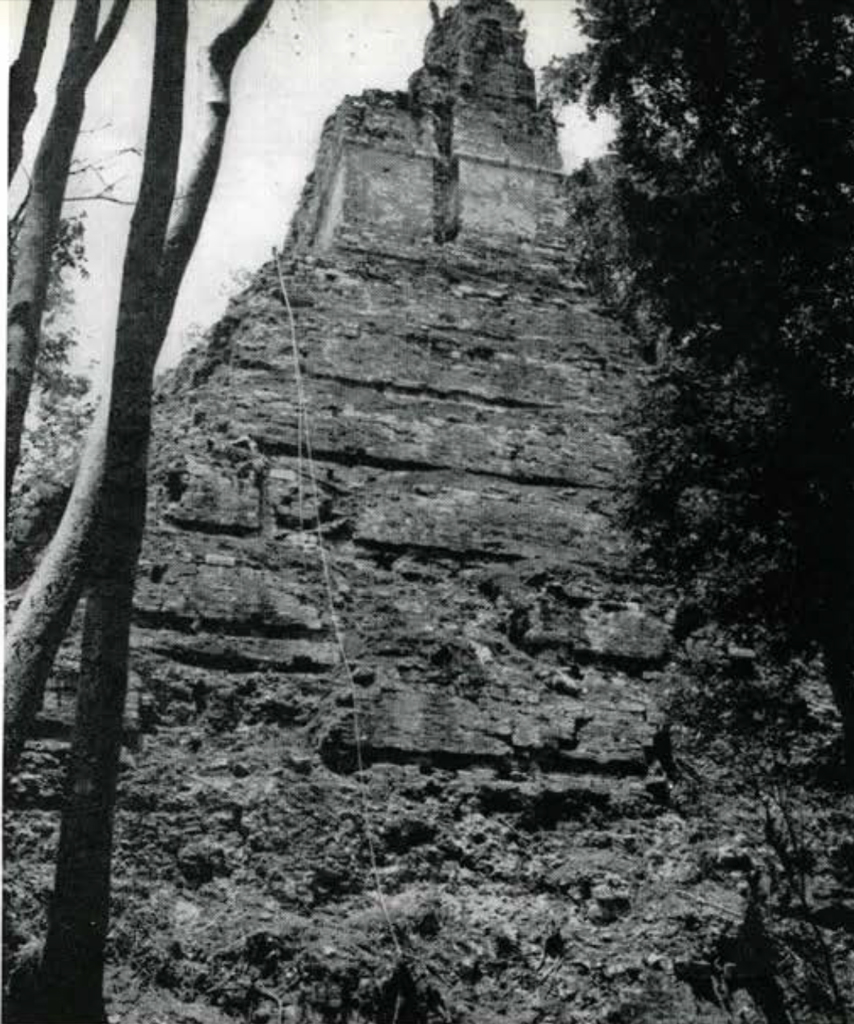

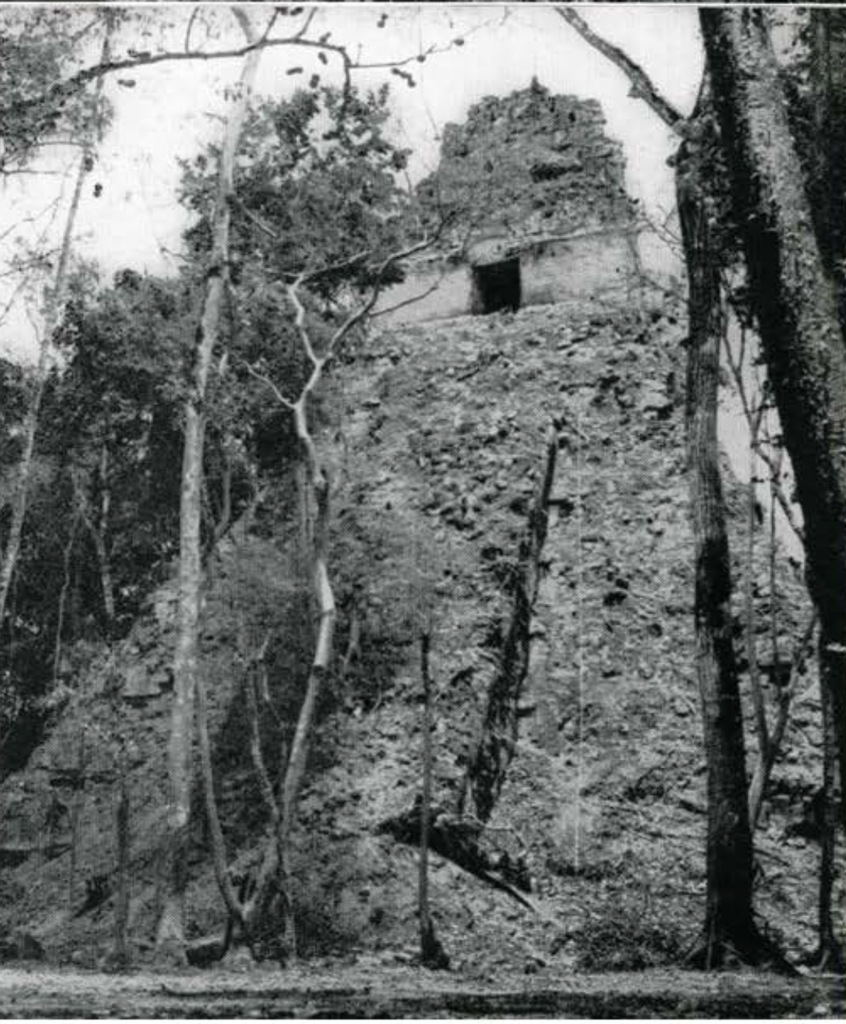

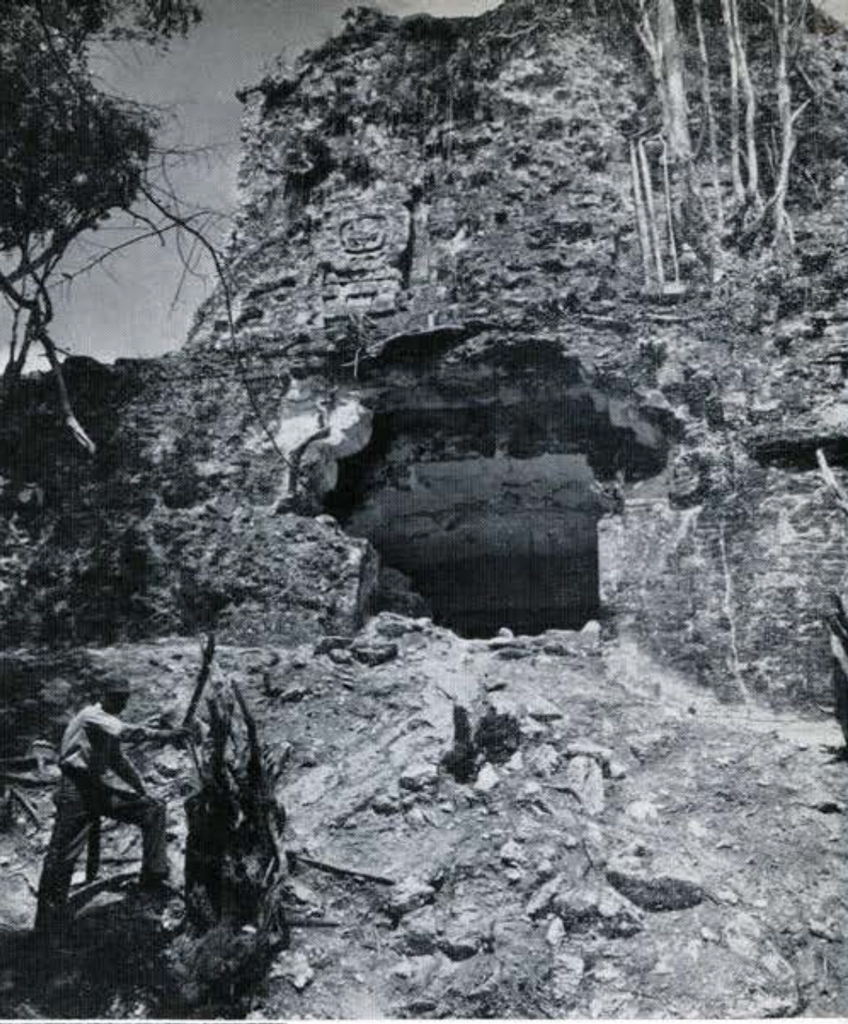

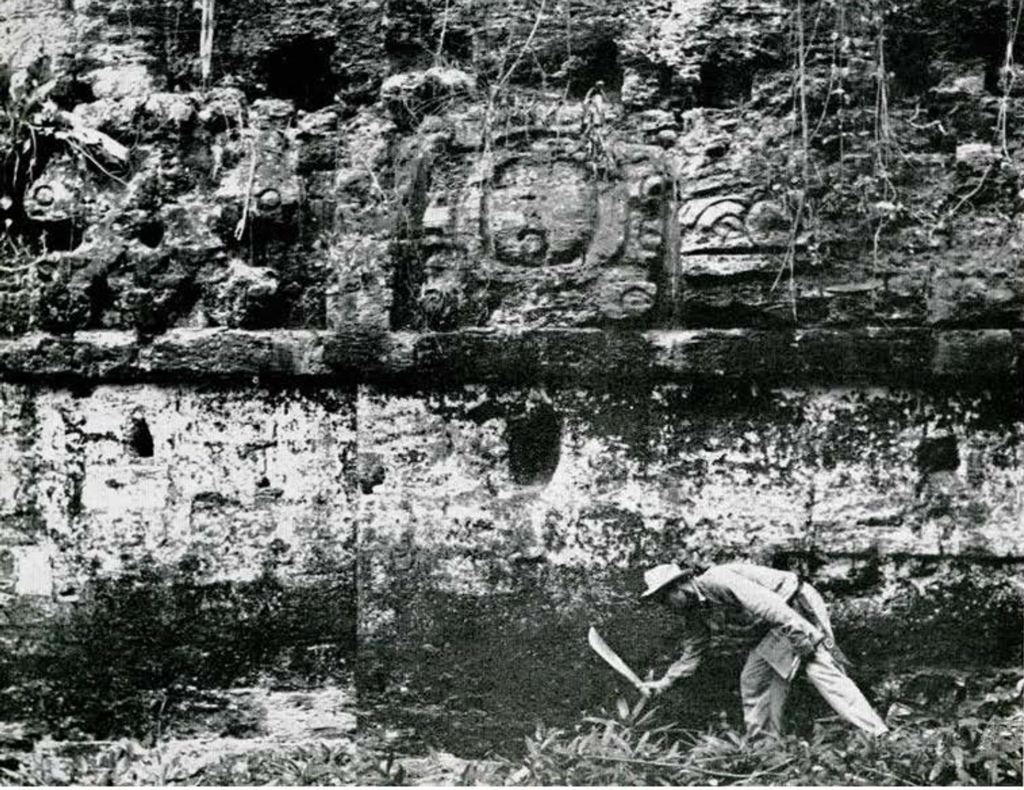

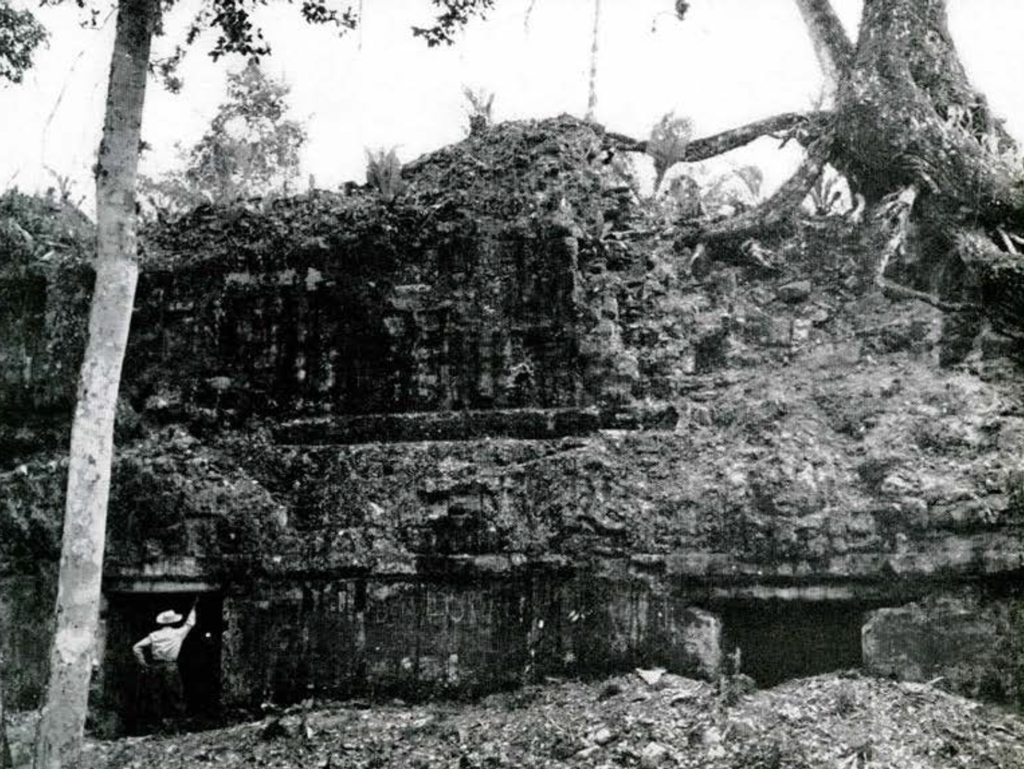

Every visitor has been astonished at the great size of the place, and by the heights of five of its dozens of masonry temples. Thinking of what ought to be done, they have been appalled both at the size of the buildings and at the enormous task of clearing, excavation, and restoration, necessary before the real significance of Tikal could be made known to the world at large. But each visitor had returned an enthusiast for a Tikal project of the future.

As early as 1948 Linton Satterthwaite, Percy Madeira, Samuel Eckert and I set up a tentative plan of campaign at Tikal and enlisted the whole-hearted support of John Dimick, who had excavated and restored the highland site, Zaculeu, for the United Fruit Company, and also of Edwin Shook, who had worked at many Maya sites in all parts of the Maya area for Carnegie Institution of Washington, had assisted Mr. Dimick at Zaculeu, and who knows Tikal better than anyone else. But at that time there were difficulties in Guatemala, as well as insuperable problems of transportation through the jungle to the site, and problems of financing work in such an inaccessible area as the Peten. Our hopes and plans did not materialize.

Now, eight years later, it is a tremendous satisfaction to see our plan put into operation by the same men who conceived it in 1948. Edwin Shook, who has come to the University Museum on leave from the Carnegie Institution for five years, completed the first preliminary season of work at Tikal last spring and is now in Guatemala arranging for the next season to begin in January.

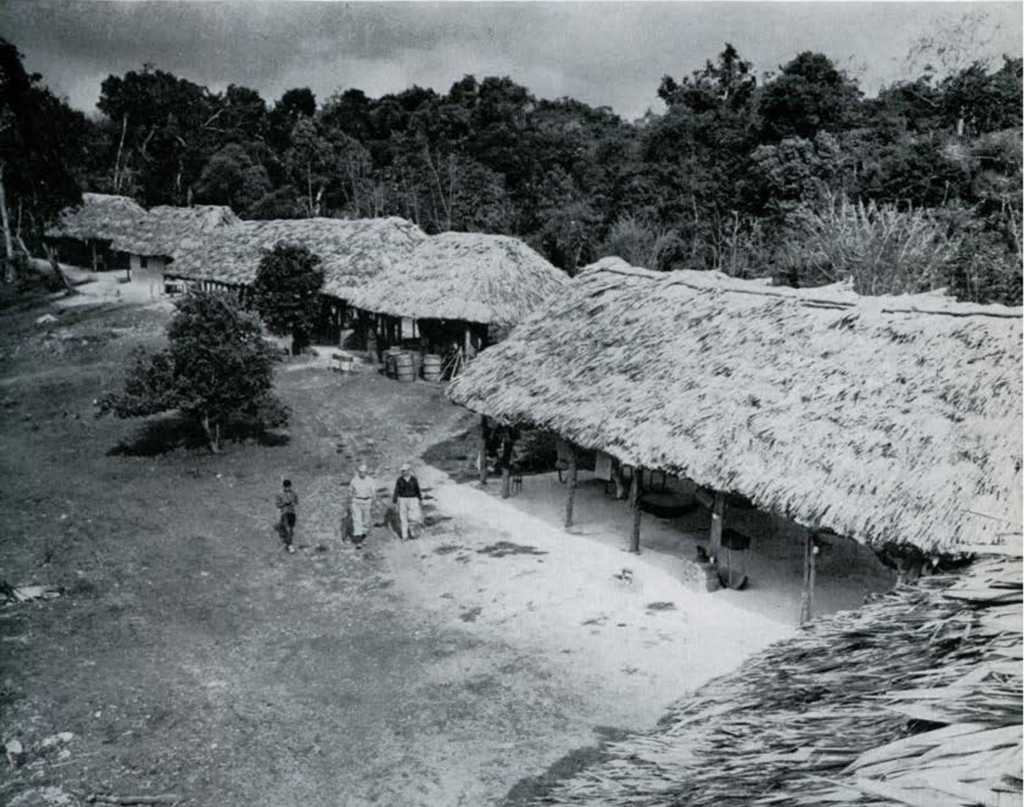

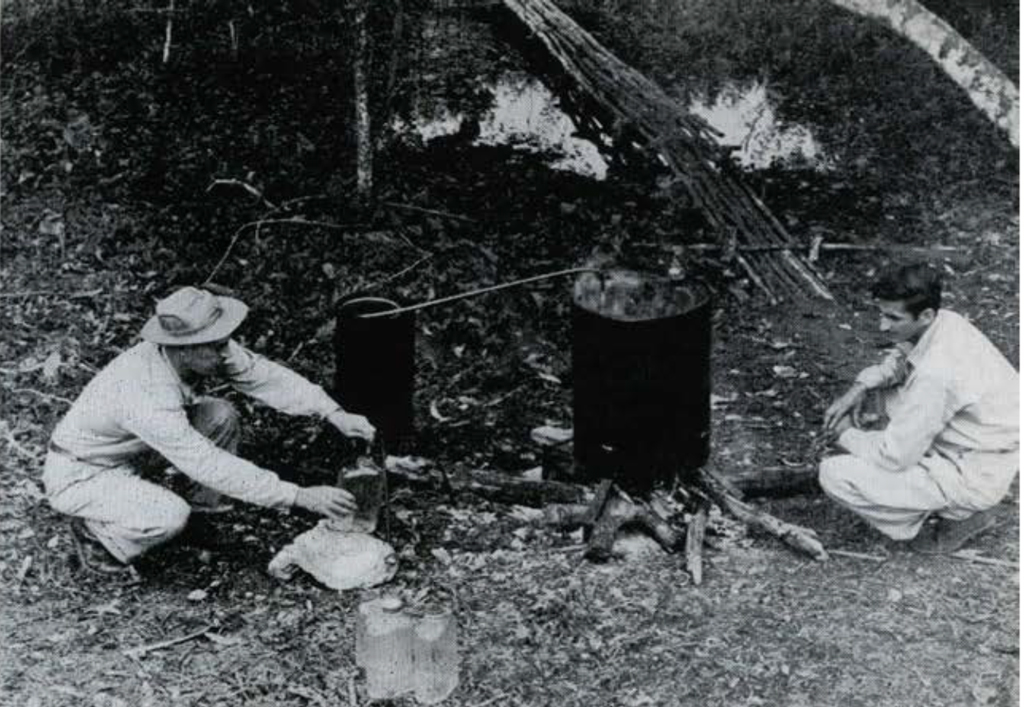

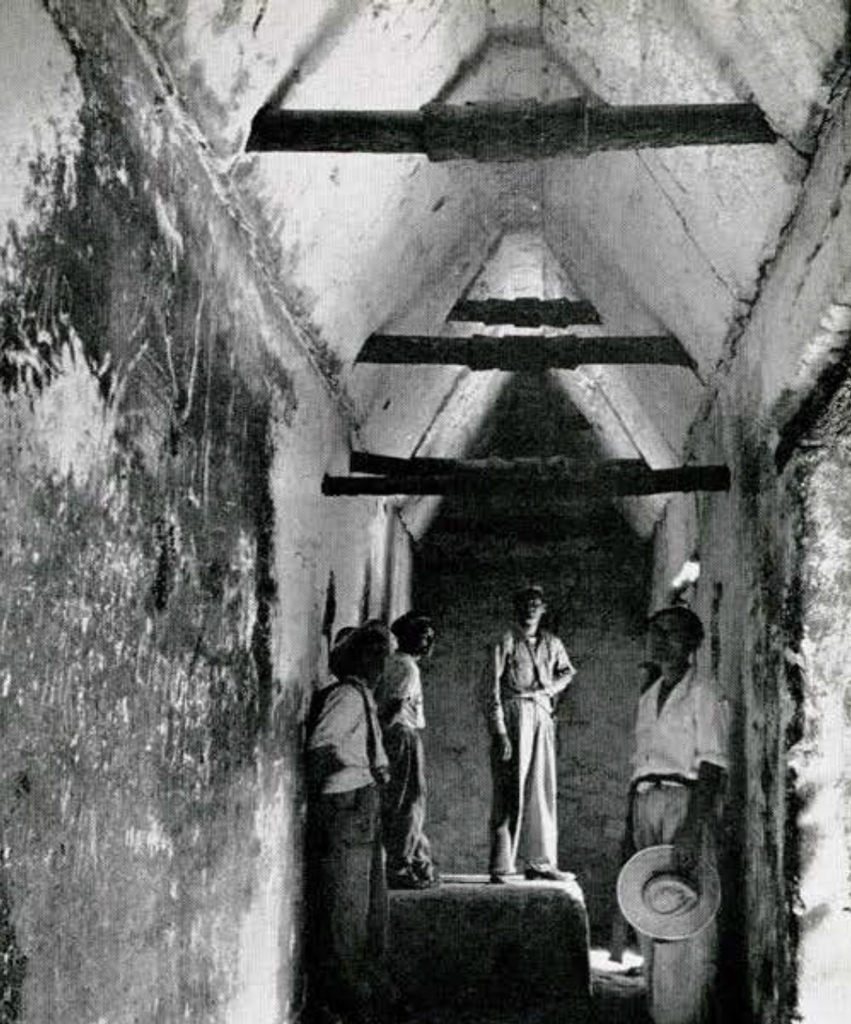

Some of his pictures, with captions based on his reports, are reproduced here. Searching for sub-surface water, “bushing,” and building a camp for the future were the objectives. Scientific results were not expected this first season, but considered as by-products, they were considerable. A companion article by Satterthwaite deals with one of Shook’s discoveries. We have established a permanent camp, cleared some 5 miles (8 km.) of roads through the ruins, and cleared the Central Court with the Acropolis to the south of it, an area of 12 acres (5 hektares). The first season has also resulted in the discovery of many new structures, including a new ball court and the discovery that the area of ceremonial courts and buildings is even larger than supposed. It is now estimated at more than six square miles (16 sq. km.). A 60-foot open well through solid hard limestone failed to reach water. This basic problem is yet to be solved. Clearing and exploration will continue this coming year while excavation begins.

Image Number: 56-3-48

Image Number: 56-3-3

All this has been made possible by changing circumstances in 1955. An air field constructed by the Guatemala Government at Tikal itself has at last made major work there a practical possibility. But even more important is the sincere and enthusiastic support of Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, President of the Republic of Guatemala, and many other Guatemalans such as Carlos Sameyoa C., Director of the Institute of Anthropology and History, Antonio Tejeda, Director of the National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, and Lie. Adolfo Molina Orantes, Member of the President’s Council. Many other friends in Guatemala, not in government, aided our Field Director in countless ways. Together we all embarked upon a Guatemala-U. S. venture in cultural relations which will result in the rediscovery of America’s greatest monument to its ancient civilization.

This cooperation, it seems to me, is dramatically illustrated in the figure which shows a Guatemalan Air Force plane unloading supplies for the expedition at Tikal. The Government supplies air transport of materials and men; without such very material help from Guatemala our venture would be impossible. President Armas has twice during the last season visited the expedition camp at Tikal and has personally arranged to establish radio communications between the camp and Guatemala City. The Guatemalan Government maintains the air field there and now commercial airlines have begun to fly in plane-loads of visitors from the North as well as Latin America.

Our most urgent problem at the moment is water. In the dry season when we can work at Tikal there is no water supply except a catch-basin of rain water. This normally runs dry in April and at best cannot supply the necessary number of workmen. Edwin Shook, our Field Director, upon whom most of the burden of the whole operation must necessarily fall, is at the moment arranging to air-lift well-drilling equipment into Tikal from Guatemala City. It may be necessary to drill as much as 300 feet to reach a permanent water supply and we need at least two wells to supply the camp and air field.

Image Number: 56-3-6

Image Number: 56-3-34

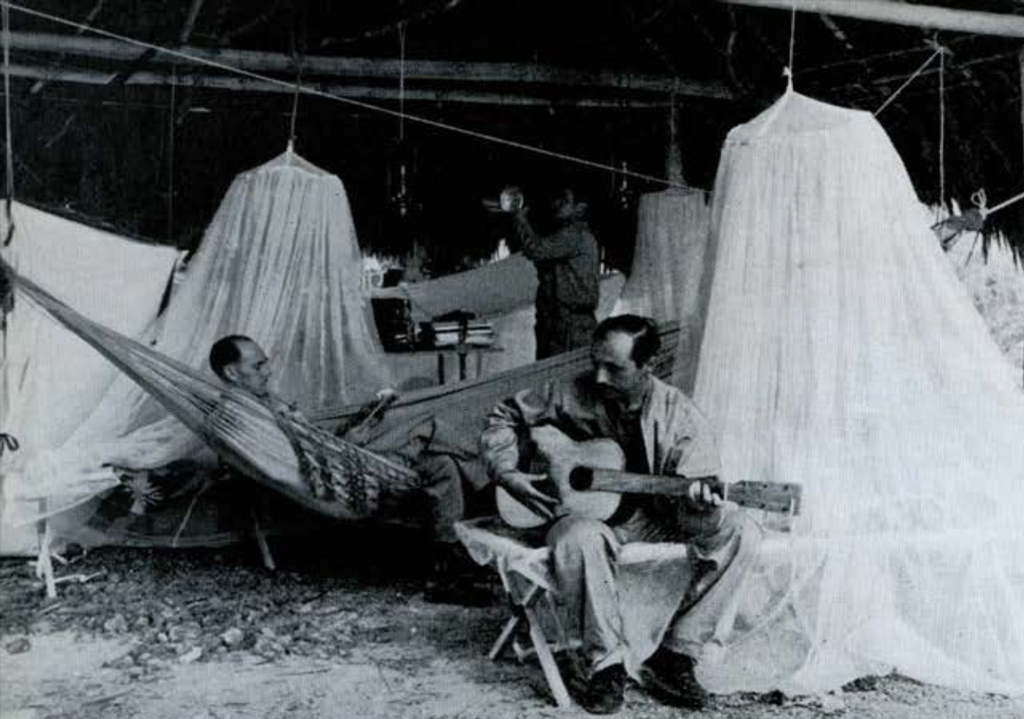

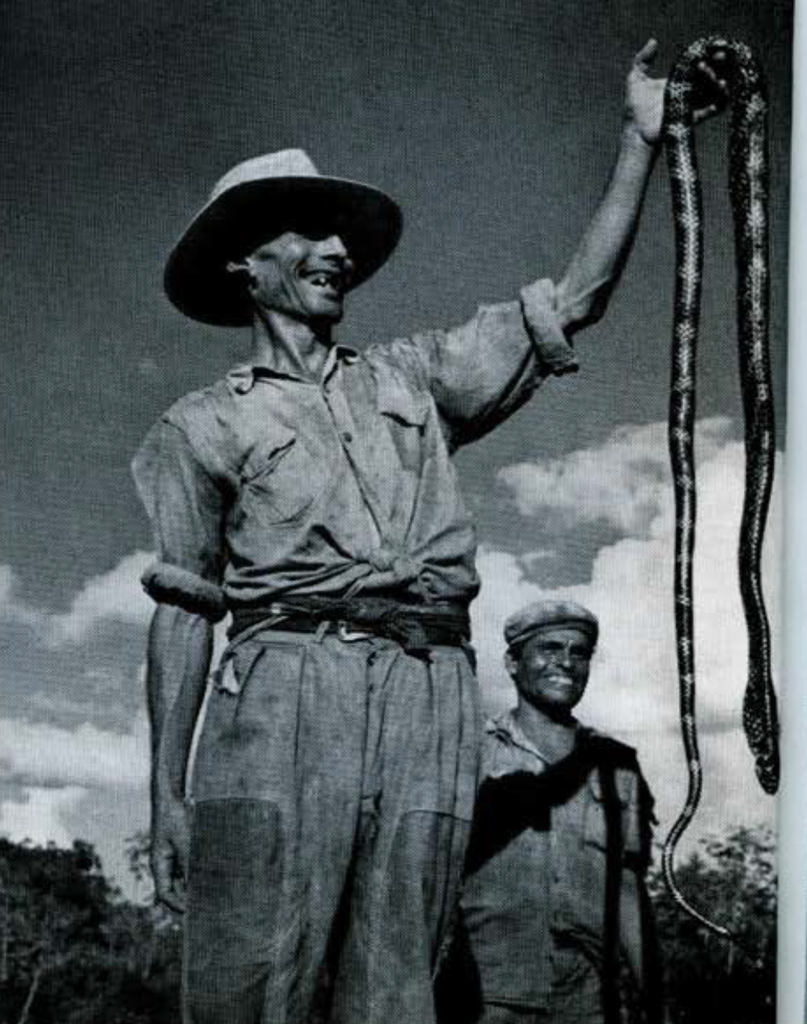

Last season our party at Tikal consisted of Shook, Peter Mack, George Holton, and Antonio Ortiz, with Linton Satterthwaite temporarily there during the excavation period. But in addition, collaborating with the Museum’s expedition, was a party of naturalists from the University of Michigan: T. H. Hubbell, L. C. Stuart, I. J. Cantrall, and Paul Basch. All of these men with 40 workmen and many visitors were a heavy drain on the scanty water supply. But it is part of our plan to encourage collaboration with other scientists eager to work in the little known jungles of the Peten, believing that this is useful to the whole project and to the opening up of the Peten.

The area of Tikal has been declared a National Park, and it will not be invaded by oil rigs which are expected to appear all around it. As soon as permanent water is found, private enterprise will undoubtedly install hotel facilities for visitors. It is part of our plan to help tourists learn about the past by seeing some of its greatest products face to face. Tikal is being opened up not only for archaeologists, but for the people of America in general, who support them.

Our belief in the significance of Tikal is justified, I believe, by the nation-wide response to the announcement in American papers that we would undertake its exploration. Response from people like Colonel Truman Smith and Phoebe Gilkyson, who have long urged the study of Tikal, is not surprising. But letters of encouragement have come in from all over the country, some with contributions toward the work by people knowing little about the Museum or of its years of work in Middle America. Others, like Ambassador Spruille Braden and Mr. and Mrs. John Dimick are giving much of their time and energy to advance the long-term project, believing as we do that the rediscovery of this great city in the jungle will be a major contribution to our study of human history and to the best kind of cultural collaboration with our Latin American neighbors.

Image Number: 56-3-24

Image Number: 56-3-41

Our belief is also justified by the financial support we have already received from the American Philosophical Society, the Rockefeller Foundation, and from a very generous individual who desires to remain anonymous. With such aid, augmented by contributions by members of our Board of Managers and other individual friends, and added to regular Museum research funds and the active support of the Government of Guatemala, we shall be exploring, clearing the forest, and excavating for a minimum of five years.

But we are arming at a 10-year program, and at consolidating the masonry of the New World’s tallest and most beautiful temples. As some of Shook’s pictures show, after a thousand years these are still magnificent, but each year takes its toll and some of them are in danger of sudden and complete collapse. Much repair work is needed, and soon, but it cannot be done without many modest and some very large contributions. Our hope is that by opening up the site and getting started, the need will become apparent to those who can help to meet it. We shall be probing the buried levels for information on origins of perhaps 2,500 years ago and on the growth of Maya civilization thereafter. We shall be “saving” the great temples and palaces at the surface by recording them on paper. But we want also to save them actually, a task which we owe to the future. There is a great chance here for those who are fascinated by the great monuments of the past. The success of the more ambitious part of our plan depends on them.

If we succeed, Tikal will become a breath-taking experience for countless people, and it will teach them directly that a stone-age technology and a hostile environment did not here prevent development of true civilization.

Image Number: 56-3-33

Image Number: 56-3-40

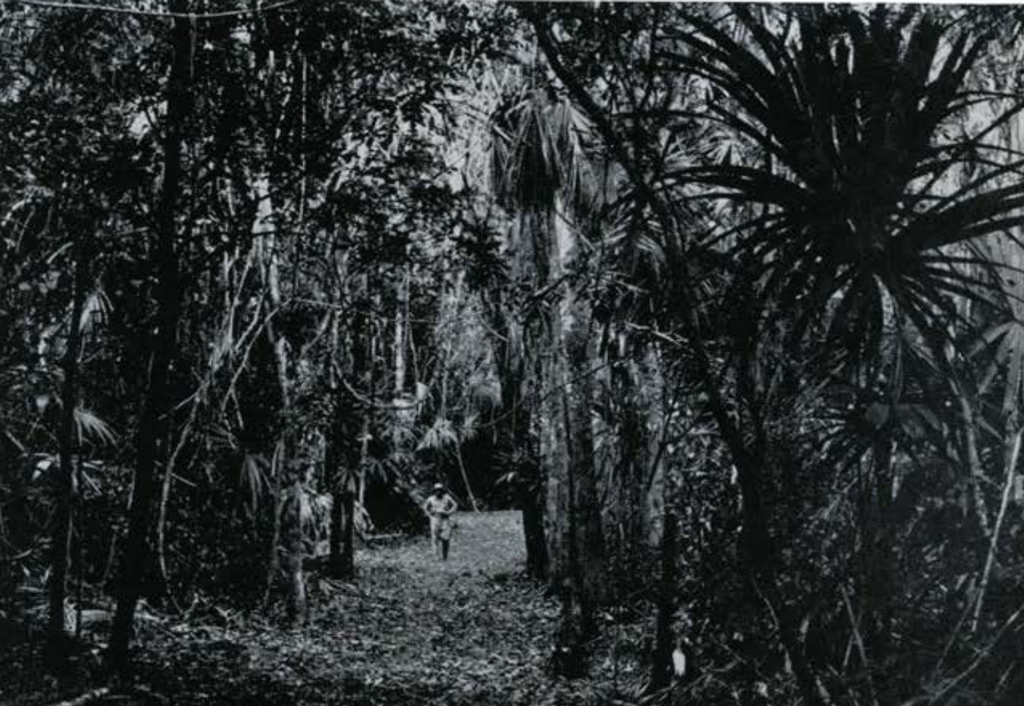

Image Number: 56-3-21

The trail would become choked with fresh growth and newly fallen trees within a year unless kept in shape by a skeleton crew during the long rainy season. As long as it is properly maintained one may walk as in a park, getting the “feel” of the undisturbed tropical forest on either side. Monkeys are frequently overhead. Shooting has been forbidden and one hopes they will remain unafraid.

Image Number: 56-3-11

Image Number: 56-3-12

Image Number: 56-3-14

Image Number: 56-3-69

Image Number: 56-3-72

Image Number: 56-3-73

Image Number: 56-3-88

Image Number: 57-3-100

Image Number: 56-3-64