Since John L. Stephen’s remarkable and justly famous account of his diplomatic journey (1839-1842) and archaeological discoveries in Central America and Mexico, interest in and study of the Pre-Columbian remains in those regions have increased steadily. A long period of exploration followed in Stephen’s wake and it continues to the present day. The results combined with those of many scholars studying historical source material quickly demonstrated that the Maya Indians of southeastern Mexico, Guatemala, and northwestern Honduras had achieved one of the most advanced civilizations in the Western Hemisphere prior to the coming of Europeans in the 16th century.

Another approach to the study of the Maya began shortly before the close of the 19th century with the excavation of their ruined cities. Continued excavation since and research during the past few decades among the living Maya have enormously increased knowledge of the ancient and modern Maya and their neighbors. In spite of a century of investigation, varying in intensity of effort from time to time, there remain major unsolved problems relating to them and other aboriginal peoples of the New World.

How did the Maya master a seemingly inhospitable lowland, tropical forest environment and develop a civilization to the degree that is evident in their great religious and civic architecture at Tikal, Piedras Negras, Palenque, Copan, Uxmal, Chichen Itza, and hundreds of other ruined cities; their magnificent art in stone, stucco, wood, pottery, wall painting; their hieroglyphic system of writing and accurate reckoning and recording of time? Why, after several thousand years of occupation, were most of the great cities abandoned and many regions partly or wholly depopulated?

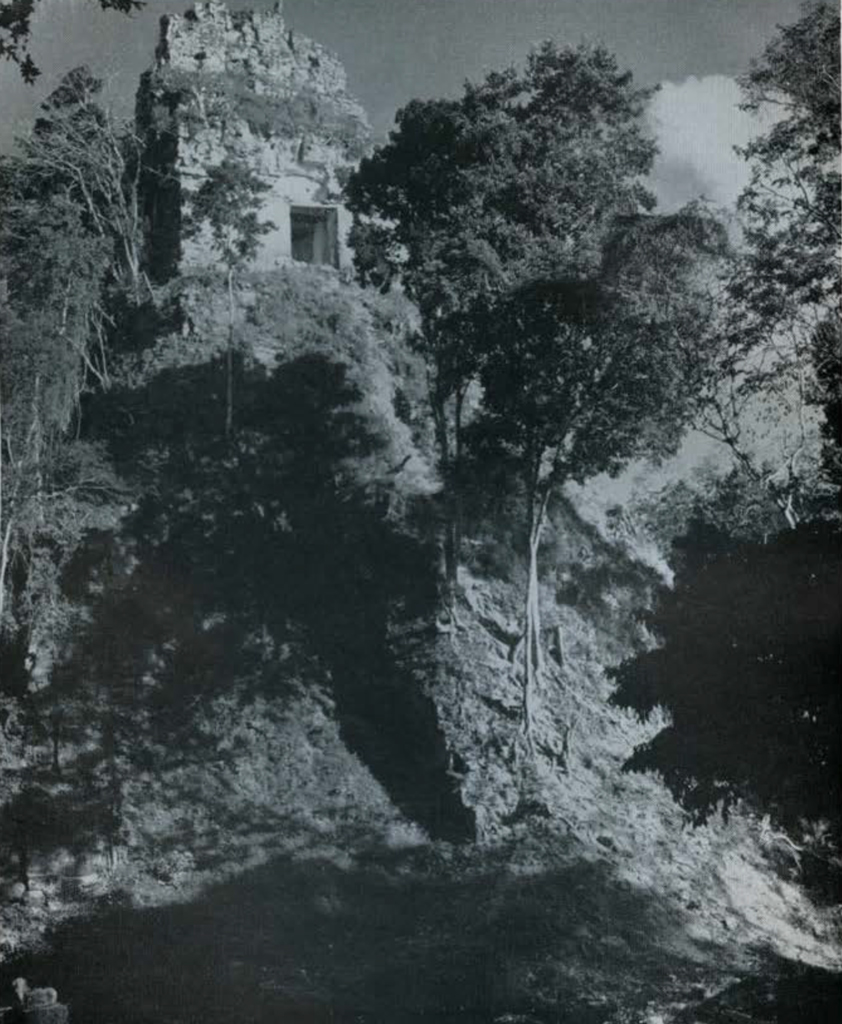

Tikal, located in the heart of the Maya “Old Empire” or Classic Maya Lowlands may hold the answer to such problems as the origin, long development, florescence, and collapse of the Classic phase of Maya civilization. This metropolis, abandoned over a millennium ago to the destructive forces of tropical vegetation and climate, even today retains ruins of pyramid-supported temples equal in height to a modern twenty-story skyscraper, numerous lesser temples, multi-chambered palaces, a host of other religious and civic buildings, causeways, reservoirs, and uncounted house foundations of a teeming population. The whole, spreading over an estimated sixteen square kilometers, is now enveloped and largely obscured by the dense tropical forest which covers most of the Yucatan Peninsula.

In the December 1956 issue of this Bulletin (Vol. 20, No. 4), Froelich Rainey has discussed the University Museum’s interest in Tikal and its tentative plans in 19-1-8 for work there, plans which could not then be carried out because of the inaccessibility of the site, but which have now been made possible by the clearing of an airfield at Tikal by the Guatemalan Government. In that article Dr. Rainey has outlined plans for a long-term project of excavation and reconstruction in cooperation with the Guatemalan Government, and he has also summarized the results of the first season. It is my purpose here to give some details of the 1956 work and to report on the 1957 season.

Early in January 1956, a transport plane of the Guatemalan Air Force landed at Tikal with the first University Museum expedition. It consisted of the writer, three biologists from the University of Michigan, a crew of twenty-five native workmen, baggage, equipment, and food supplies. \Ne found nothing more than several dilapidated palm-thatched huts on the fringe of the airstrip surrounded by the towering green forest which seemed to threaten to engulf the tiny clearing. The workmen slashed away with axes and machetes, gradually enlarging the clearing. Then they made temporary lean-tos thatched with a few palm leaves to shelter each man in a hammock from the rains which fell sporadically. More supplies and equipment arrived by plane, and slowly the lean-tos gave way to houses made of pole and thatch-all material wrested from the surrounding forest. These provided better sleeping quarters, cooking, eating, and storage facilities for the workmen and staff. Once the basic needs of living and working were taken care of, our attention turned to clearing the principal ruins and opening roads and trails to them, and to searching for water. The extreme scarcity of water, available only from shallow surface pools of stagnant rainwater, became more and more serious as the dry season progressed . T he limited supply was ration ed carefully. Nevertheless, by late April, the pools dried up and water to maintain the men in Tikal had to be flown in by plane. We attempted to dig wells by hand, one to a depth of fifty and another to sixty feet, without finding water. Work in the second well continued day and night without stopping for over a month. We encountered hard, crystalline limestone through which little progress could be made without power tools.

Obviously one of the main objectives of the 1957 field season was to procure a permanent water supply for the Tikal Project. We believed that this might be done with well-digging machinery. For this purpose, a heavy well-rig was purchased in the United States last fall, shipped by boat to Puerto Barrios, Guatemala, and air-transported piece by piece to Tikal. It took until February 1, 1957, for the last parts to reach camp and well drilling began the next day. The first machine-dug hole reached a depth of sixty- six feet, the second five hundred and thirty feet, the limit of the drill, and the third penetrated five hundred and two feet without striking water. The last well site was selected by a famous water dowser. Further drilling had to be suspended for lack of water to maintain operations. Another attempt to find water will be made later this year when heavy seasonal rains provide sufficient water to operate the well-rig. Should this effort also fail, the next step will be to improve the drainage into, and then clean and deepen several of the large artificial reservoirs built by the ancient Maya. We discovered three reservoirs the first season and three more in 1957, which, with one previously known, bring the known total to seven for the site. Several still retain water for a brief time after each rainy season despite being choked with vegetation and silt and having been unattended for more than a thousand years. We think it possible to catch and store sufficient rainwater in these Maya reservoirs during the off-season to supply our needs in the dry months from January through May.

In 1957 the Guatemalan Government lengthened and improved the Tikal airfield; transported by Air Force and Aviateca planes approximately 100,000 pounds of equipment and supplies in addition to personnel and baggage; established and maintained radio communication and regular air service twice weekly from Guatemala City; supplied most of the workmen who built five miles of roads from camp to outlying water holes. We acknowledge with deep gratitude the valuable assistance and contributions rendered by the Guatemalan officials. The late president, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, visited Tikal in April for the third time and as always gave his unstinting and enthusiastic support to the Tikal Project. He appointed Colonel Ramiro Gereda Asturias as liaison officer to expedite government assistance to the project.

In spite of our preoccupation with well drilling, camp and road building, substantial progress was made on the archaeological project. Exploration of the central ruins and the surrounding area in the two field seasons brought to light seven previously unknown stone monuments: one carved altar (Altar X), two plain and four sculptured stelae (Stelae 22-25) . The total number of stelae now known from Tikal is ninety-three, of which sixty-eight are plain. We also discovered the six artificial reservoirs mentioned previously, a ball-court, several minor ceremonial groups and a large one of temple and palace structures, and an as yet uncounted number of house-mounds, “chultuns” (bottle-shaped pits, possibly for storage), and ancient quarries. This exploration disclosed that the arbitrary limits of sixteen square kilometers we propose to map in detail do not encompass the metropolitan area of Tikal. House foundations and small civic and ceremonial buildings continue for some distance on the east and south beyond our assumed map boundaries.

The second University Museum expedition to Tikal reached the site early in January 1957 and remained in the field until late May. Many individuals took part in the investigations from time to time. Those on the staff who remained the full season included the writer as field director; William R. Coe and Vivian L. Broman, archaeologists; James E. Hazard, engineer; Walwin Barr, photographer; and Antonio Ortiz, foreman.

Through the kind efforts of J. 0. Kilmartin of the U. S. Geological Survey, we obtained the services of a topographic engineer, Morris R. Jones, for one month. Jones, assisted by Hazard, Coe, and Broman, began the arduous task of mapping Tikal where the dense vegetation often limits visibility to a few feet. He also trained Hazard and Coe so that they can continue this important survey. They completed one square kilometer of the site map on a scale of 1:2000 with contour interval of one meter. This detailed map of Tikal, indispensable to the research program, also will be a major contribution to Maya archaeology. It will represent the only large Lowland Maya site intensively surveyed for some distance beyond the nucleus of the more impressive public buildings.

The staff jointly initiated controlled excavations at Tikal in late January and minor digging continued through the season. In these various operations we received assistance and advice from Froelich Rainey, Alfred and Mary Kidder, and Linton Satterthwaite during their stays in camp.

The first excavations were in a newly discovered group south of the Temple of the Inscriptions. There, while hunting, two of our native workmen observed and reported the top of a carved stela (Stela 23) protruding above the ground at the base of a small pyramidal mound. Upon clearing, Stela 23 turned out to be not a complete standing monument as we expected, but only the upper half of an Early Classic one. The sculpture, at some time, had been deliberately mutilated and broken by the Maya, then later the upper half was re-set before the stairway of a Late Classic pyramid and temple. A cache of eccentric flints and obsidians beneath the stela fragment also had been re-deposited, presumably salvaged by the Maya from the original cache under Stela 23. Coe and Broman continued excavation in the area in an unsuccessful search for the lower half of Stela 23. Their work disclosed a long series of building activity, three minor burials, and a crypt vault containing fragments of human bone and two pottery vessels.

Near the above group, Hazard and Ortiz while blazing a trail to Aguada Naranjo, stumbled upon another early monument, Stela 25. It lay face down on the ground, apparently unassociated with several mounds nearby. This sculpture, like Stela 23, had been broken in ancient times and its principal figure and hieroglyphic text partly effaced. The surface of the broken edges had been evened by stone pecking. These two newly discovered examples of willful destruction of carved monuments by the Maya led us to re-examine other early stelae at Tikal. Satterthwaite, who undertook this work and the study of available hieroglyphic texts at the site, determined that many of the early monuments had been broken in ancient times and that only fragments of the original sculpture were re-erected at some later date. The violence thus indicated may have been responsible for the end of the Early Classic period and perhaps for the hiatus in the known sequence of inscriptions at Tikal.

Broman and Ortiz supervised the additional clearing in the Main Plaza, in a twin pyramid complex which includes Stela 16 and Altar V, and in another complex in Group E where Stela 22 and Altar X were discovered in 1956. The bushing of the two twin pyramid complexes and the examination of three others verified our observation that the Tikal Maya developed a unique architectural assemblage and repeated it five times at definite intervals of one katun or twenty Maya years. Each complex consists of a court with a single stela and altar set in an enclosure on the north side, facing a vaulted building directly opposite on the south side. Identical pyramids are on the east and west sides. These are flat-topped and have a stairway on each of their four sides. Invariably, the east pyramid has a row of plain stelae and altars on the court level at the foot of its west stairway. Both pyramids have a perfectly square, level top. It is certain they carried no masonry structure but may have had a pole-and-thatch temple.

Of the five twin temple complexes in Tikal, four have dated monuments within their enclosures and one has a plain stela. The dates in the Maya system on the carved stelae are 9.14.0.0.0, 9.16.0.0.0, 9.17.0.0.0, and 9.18.0.0.0. The missing date, 9.15.0.0.0, may be represented by the plain stela in the one undated complex. These dates are discussed in some detail by Linton Satterthwaite in Vol. 20, No. 4 of this Bulletin.

Miss Broman excavated beneath several of the plain stelae aligned on the court side of Structure 78, the east pyramid of the 9.17.0.0.0 complex. She recovered no sub-stela caches nor evidence of any construction predating the twin pyramid complex.

We gave special attention to the plain and carved wood lintels remaining in the five great temples. Coe painstakingly cleaned, photographed, and made accurate drawings of the sculptured beams in situ. There remained two of the four beams over the second doorway of Temple I and nine of the ten beams forming the lintel over the rear doorway of Temple III. These nine beams are superb examples of Maya wood sculpture and previously had not been recorded. Coe and the writer carefully measured the missing beam impressions in Temples I-IV and it seems quite certain that replicas of the sculptured Tikal beams on exhibition in American and European museums can be replaced in their original positions. Through the kindness of Dr. Alfred Bühler and Mr. Adrian Digby we are receiving latex molds of the Tikal carved lintels now in museums in Basle and London. From these we plan to cast plastic replicas. They will be attached to concrete lintels and installed in Temples I and IV from which we are now quite sure the originals came.

D r. Lester C. Walker, Jr., of the University of Georgia spent several weeks in Tikal recording the etchings on the interiors of many of the better preserved temples and palaces. These random drawings, illustrating a variety of human activities, birds and animals, occur on the lime-plastered walls, vault faces, door jambs, and floors of standing buildings.

Bert Noble, a consulting engineer, rendered invaluable assistance to the Tikal Project. He not only gave generously of his time on our camp problems, piloted us on urgent trips to and from Guatemala City, Puerto Barrios, and Tikal, but inaugurated an important phase of the archaeological program, that of repairing the many badly shattered carved monuments. This exacting work was started on Stelae 12, 23, and 25.

We have made available, on a cost sharing basis, the facilities of our field camp to qualified students in all branches of research which may throw further light on the Maya. In 1956 scientists from the University of Michigan began studies in entomology, herpetology, and conchology. During the past season, Frank B. Smithe and Raymond A. Paynter, Jr., of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, initiated a study of the bird life at Tikal. We will do all that we can to encourage such cooperative programs on fauna, flora, climate, and geology of the region, since a more thorough knowledge than we now possess of the lowland tropical environment in which the Maya lived is essential to an understanding of their brilliant achievements.