During the summer of 1957, excavations at Hasanlu, near the south shore of Lake Urmia, were carried out as part of the Hasanlu Project of the University Museum and the Archaeological Service of Iran. The work was directed by the author, assisted by Mr. Taghi Assefi, Inspector of the Archaeological Service who also served as staff artist, and Mr. J. Brewster Grace of Philadelphia who served as general assistant; Dr. M. T. Mostafavi and his staff provided full cooperation on behalf of the Iranian Government; while Mr. M. T. Djanahmadlou and his son, Mr. A. A. Djanahmadlou were our gracious hosts at the site. Visitors during the season included Dr. Froelich Rainey, Director of the University Museum; Mr. Ralph E. Jones, Assistant Regional Director for Azerbaijan of the United States International Cooperation Administration; Mr. Harold G. Josif, United States Consul at Tabriz; and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas and his party. On both arrival and departure the expedition enjoyed the traditional hospitality of Dr. and Mrs. John Elder of the American Church Mission in Teheran.

The major objectives for the season’s work at Hasanlu were first, to explore the stratigraphy of the Outer Town; second, to document burial customs and recover skeletal material; and third, to link the two soundings made in 1956 (reported in this Bulletin for March of that year) on the central Citadel mound, Operations I (formerly A1) and II (formerly C9), and in so doing to shed light on the final occupations of that area.

Image Number: 73784

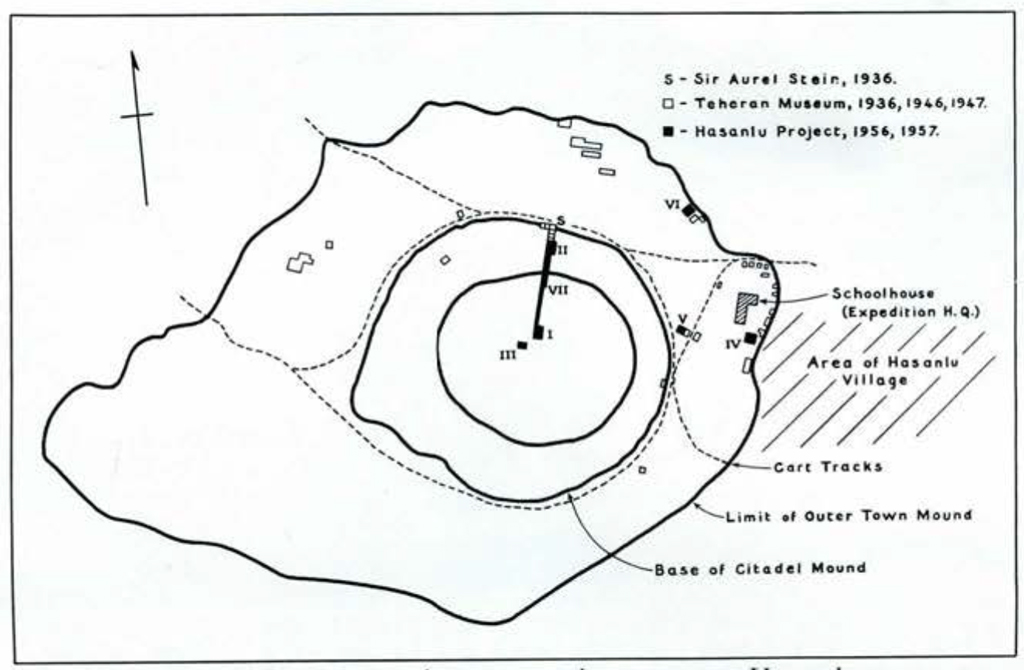

THE OUTER TOWN

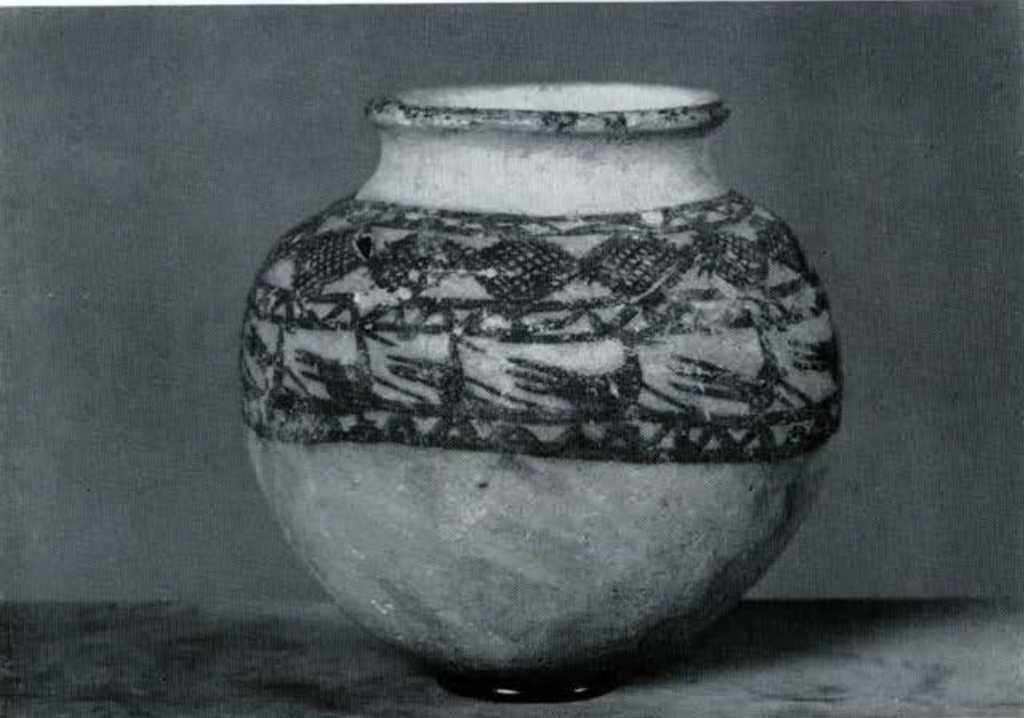

To accomplish the first two objectives Operations IV, V, and VI were undertaken in the eastern and northern areas of the Outer Town. Operation V penetrated eight and a half meters to virgin sand and the water-table. The other two soundings reached the same basal period but were not completed to virgin soil. The Outer Town was built directly upon this clean sand. The lowest occupational debris is very black in color and consists of small domestic mud brick structures, scattered potsherds, and humus. It is quite clear that these strata do not comprise an ancient lake bed as has been suggested. This initial phase of occupation has a depth of up to two meters. In the case of Operation VI it ended with the burning of the house occupying that area. These small houses are entirely of brick with clean clay floors. The pottery is characterized by a type of carinated bowl, and more particularly, but less commonly, by globular vessels with short vertical collars and everted rims. The paste shows granular inclusions and the light orange surface frequently has a micaceous glitter. Geometric patterns in a matt paint of purplish brown color ornament the shoulders of the vessel. In one instance a row of birds was added below a zone of cross- hatched lozenges (Fig. 22).

One complete burial, VI B21, was recovered in which the body of an adolescent child lay on its right side in a slightly contracted position, oriented east-west with its head to the west and facing southeast. Three large jars, each containing smaller ones, had been placed at the feet. Another small jar had been placed in the fill above the head. The body was clad in a tunic of some sort fastened by a slender copper pin at the left shoulder. There was a coiled copper ring in the hair just over the left ear and a necklace of white paste beads was hung around the neck.

Museum Object Number: 58-4-16

Image Number: 62700

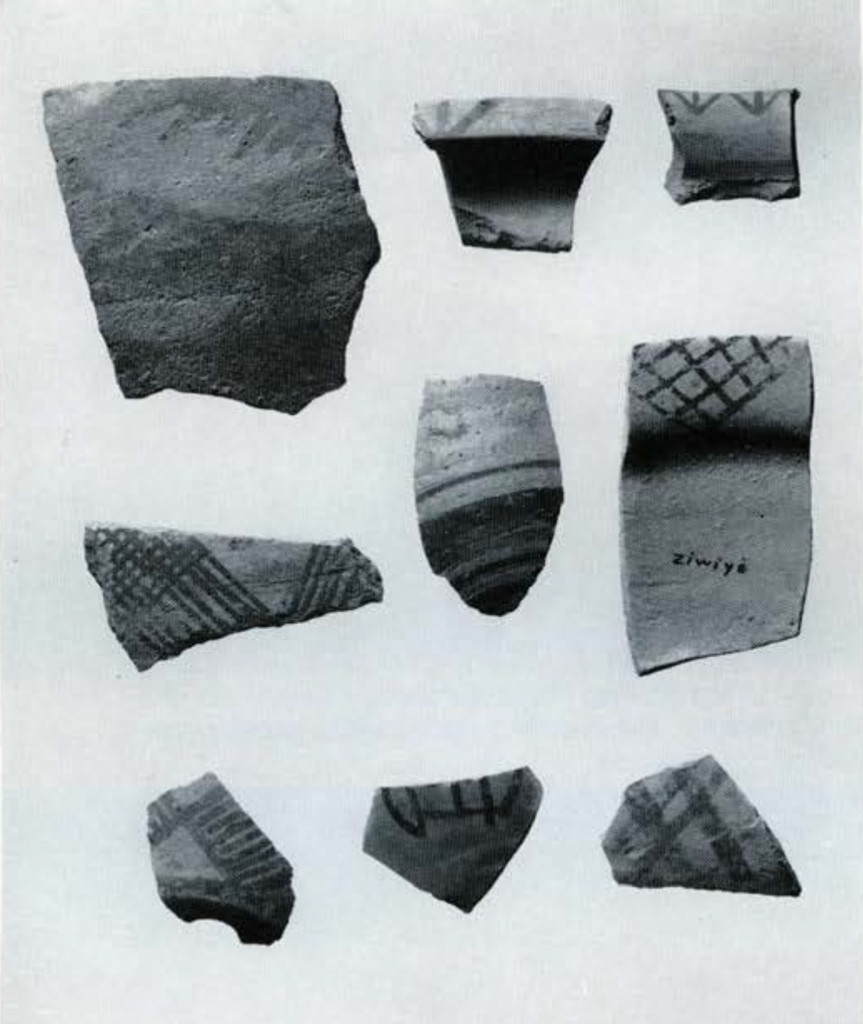

Following the “Painted Orange Ware Phase” in each operation was a period characterized by cups with button bases and loop handles, and by small vases with button bases. The former were of burnished grey pottery while the latter were of yellowish white pottery with simple bands of reddish brown paint. Stratum 6 of Operation I on the Citadel appears to correlate with this phase with the presence of painted triangles and other patterns on sherds of yellowish white pottery. Similar combinations of shapes and patterns are found in tombs at Tepe Giyan at the end of period I and the beginning of period II. This pottery belongs to the tradition of “Khabur Ware” found in Syria and Iraq, ranging in date from around 1800 B.C. to after 1500 B.C. Other varieties of painted pottery (Fig. 27) are also known from Hasanlu but have not been fixed stratigraphically.

The one undisturbed burial of this period lay on its right side, oriented east-west, with its head to the east. Three straight copper pins fastened a tunic around the neck. A copper bracelet adorned each wrist while a necklace of copper and stone beads was around the neck. Fragments of a copper ring were found loose in the fill. A small knob handle of bone lay just over the sternum. Two small vessels accompanied the burial – a grey-ware cup with button base and loop handle, and a simple painted vase with button base. The small, mud brick domestic structures of this period have accumulated a greater depth of debris on the east side of the Outer Town than on the north.

Museum Object Number: 58-4-1

The “Button Base Phase” was followed by a deposit filled with burnished grey, burnished red, and plain pottery in both Operations IV and V. In the northern area of Operation VI this period is represented by a meter and a half of unstructured fill which was used as a cemetery area. Several disturbed burials belonging to this period were encountered in Operation IV. One of these contained a short bronze sword or dagger with wooden inlay in the handle. An identical piece is known from Tomb 10 at Tepe Giyan south of Hamadan. The same type is known from Luristan and has an estimated date of around the beginning of the twelfth century B.C.

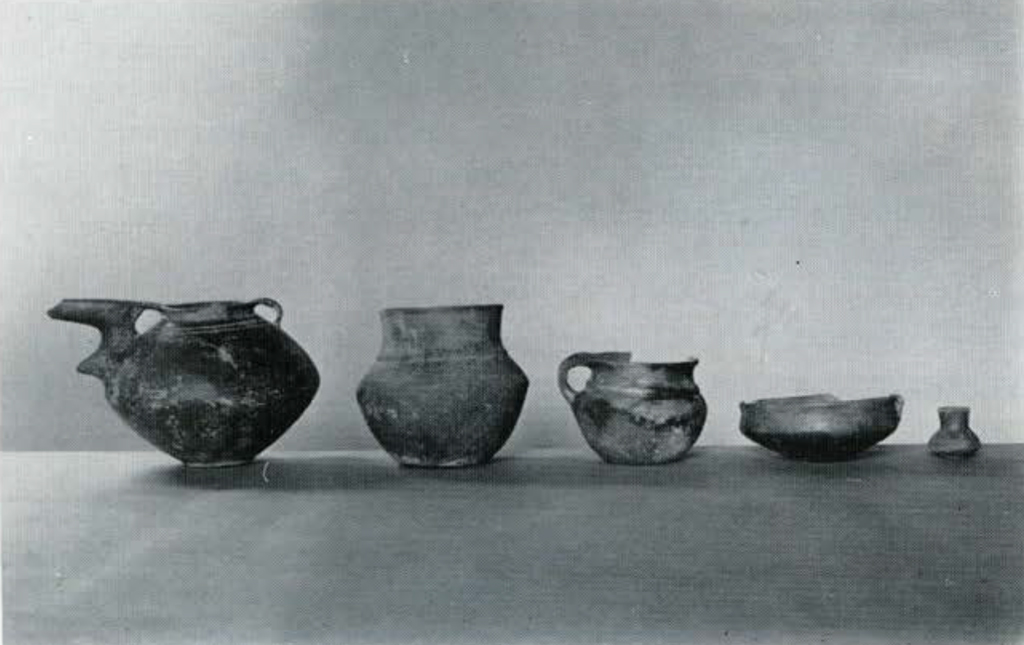

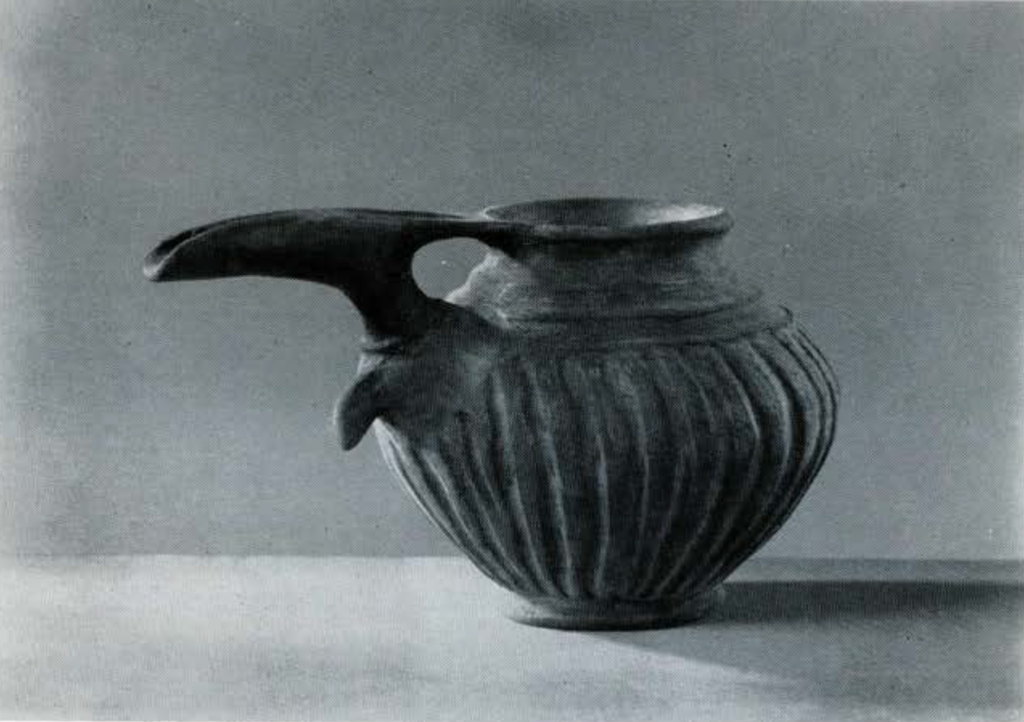

No correlation of the Grey-Ware Cemetery with other excavated levels bas yet been made. The stratum in which the graves are dug appears to have two phases, and the graves themselves obviously cover some period of time. Twenty-three graves were opened. They showed no consistent orientation or arrangement of grave furniture beyond the fact that each contained a spouted pitcher of either burnished grey or burnished red ware and several other vessels (Fig. 23). The pitchers were in great variety: some had spouts with “beards” and “ears”; some had fluted, incised, or plain bodies; some had flat, disc, or ring bases; some were with and some without strap handles from rim to shoulder; others were decorated with raised crescents; and all possible combinations of these elements occurred, but in no discernible order. Personal equipment included rings, bracelets, and anklets of bronze and iron, straight copper pins, a gold crescent-shaped pendant, a necklace of native silver pellets, bone handles with incised circles, a cylinder seal, and various kinds of beads.

Sealing the Grey-Ware Cemetery in Operation VI was a small house with stone wall foundations and a stone door socket. The pottery was a coarse, reddish buff ware including pitchers with trefoil rims and flask types of the late first millennium B.C. The material is reminiscent if not identical with Parthian pottery found at Taxila in West Pakistan. It is perhaps to this period that the cut stone column base known from the site and much of the glass picked up in the surrounding vineyards belong.

Museum Object Number: 58-4-51

Image Number: 62702

Image Number: 62703

THE CITADEL

Operation VII was undertaken on the Citadel itself to join last year’s Operations I and II. This trench cut through the final occupation of the mound, a mediaeval Islamic fortification linked with the two stone stairways reported previously. The Islamic stratum is about sixty centimeters deep and yields lime-encrusted sherds of heavy, plain-ware water jugs with flat bases and almost vertical sides. In Operation II on the north slope this stratum is represented by a deposit of superficial wash redeposited from the top of the mound. At the base of the Islamic stratum on the top of the mound one potsherd of smooth, thin, buff ware from a small carinated bowl, with triangles of brown paint around the inner edge of the rim (Fig. 27, upper right), was found. This is identical to material collected last year from Ziwiye (Fig. 27) and, together with other evidence, indicates an occupation lasting down to at least the middle of the first millennium B.C., if not later.

Only the northern half of Operation VII was carried lower than the base of the Islamic level. This section joined Operation II and revealed the heavy rock foundation and brick superstructure of a defensive ring wall beyond which lay a sloping stone pavement. This defensive wall was destroyed by fire. About a meter of debris intervenes between this destruction and the Islamic level. Below this fortification lies a stratum of burned ash from which the Carbon-14 Laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania has obtained a radio-carbon date of 2770 ± 130 years ago. The pottery is all burnished grey or burnished red. Correlation of these levels has not yet been made, and acceptance of the Carbon-14 date is of course dependent upon subsequent runs of other samples and other evidence.

To summarize briefly then-our evidence to date gives us an early level of painted pottery which at present we cannot date. Above this lies a period of simple painted and grey-ware cups and vases related to material at Tepe Giyan dating from around l 400 B.C. and later. This phase is followed by a period of burnished red and grey wares and local bronze casting dating in part around 1200 B.C. Associated with this culture, but later in date, is the Grey-Ware Cemetery with its spouted pitchers, which shares the ceramic traditions of Cemetery B at Tepe Sialk near Kashan in central Iran. This material is now dated by the excavator, Dr. R. Ghirshman, to around the ninth century B.C. Two later periods of occupation are tentatively indicated-one in the eighth or seventh century, and one in the second or first century B.C.