In the Indian villages of New England and the Maritime Provinces of Canada where the Penobscots, the Mali-sits, the Micmacs and the Passamaquoddies still occasionally exploit the old tales of their race, the good story teller, unaccustomed to make a parade of his gift, is apt to deny it altogether in the presence of a stranger. When, however, friendly intercourse has broken down the barrier of his reserve and the desire to please comes to the aid of his memory, his stock of stories often proves to be inexhaustible. If he is careful of the traditional proprieties of his craft he will tell no stories during the summer lest the listening snakes take offense. It is in winter when the snakes are asleep; when the pipes are lighted after the evening meal and the flickering firelight shows his attentive listeners through the smoke, that the Indian story teller makes his boldest excursions into the mythical past. As he weaves around his hearers the spell of his narrative the actual world is forgotten, and in its place rises a supernatural one in which the actors are beasts with human attributes.

From the stories that I have collected during the last two years I have selected for presentation here one which exhibits the main characteristics common to a large body of mythology. In making the translation my effort has been to preserve the structure of the original rather than to aim at literary form.

In this myth, the characters are the Mink (Putorius vison), the Fisher (Musteda pennanti), a member of the same zoological family, and a Snake. Fisher is a great magician, and the first part of the story brings this fact into view. In the latter part the envious Mink, the younger brother, having been driven from home for stealing his elder brother’s magic flute, encounters the Snake, who is also a magician. The unfortunate Mink, under the influence of the Snake’s magic, is powerless to resist his commands, and when he is sent to catch fish for his host, cannot choose hut obey. After an unsuccessful day’s fishing, he returns empty handed to Snake, and is informed that he himself will be eaten. He is then sent to fetch a stick, and is explicitly enjoined that only a straight stick will serve the Snake’s purpose, which, as he announces it, is nothing less than to spit the Mink and roast him in the fire; but it seems as if the straight stick formed an essential part of the Snake’s magic apparatus. While Mink is mournfully seeking for the instrument that is to be used for his own destruction, his elder brother, Fisher, taking pity on his plight, comes to his rescue and imparts to him the magic of the crooked stick. The story ends with a great demonstration of the power of Fisher’s magic as practiced by Mink in retaliation upon Snake.

THE MAGIC OF THE CROOKED STICK.

FROM THE MALISIT.

Here camps my story. A little old woman and Fisher and Mink, her two grandsons there were. The elder brother was Fisher. Off in the forest they had their camp. And the hunting was bad; then it was that they became hungry. Then went Fisher out to hunt, but just nothing he brought home. Now he spoke to his grandmother. “Grandmother,” said he, “in the bark basket is my magic flute. Shake it out for me, for I must learn where the moose are.” Thus he spoke to his grandmother, for he was a great conjurer and his flute was magic. Off he went, but behind him, following, crept the Mink, his sly younger brother. Now upon his flute Fisher blew the moose call—the moose lure.

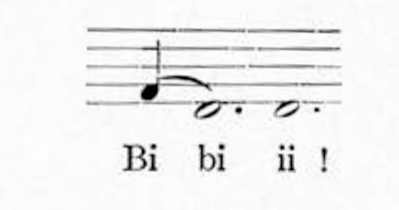

“bi bi ii.” Three times he blew. Now he could hear them dancing, those moose. Now he knew. Where to hunt them he knew. Much meat indeed he brought home that day. Now again he set out and somewhere he went, that Fisher, for a hunting he went again. But Mink, his younger brother, now stayed behind. Quietly he stole the flute; his brother’s magic flute he stole, that sly Mink. Now as he had seen Fisher do, so he blew, and the moose started dancing again. Then to Fisher came a warning and he hastened home. “Who has been meddling with that flute,” he said to his grandmother. “Nobody.” he was told. Now when he seized the flute and blew upon it, no sound would it make. That medicine flute could be used only by the owner. Now was Mink in sore trouble. Whipped indeed he was, and sent away to roam. Is it not so with him even to this day?

So he went traveling, that Mink, till it began to grow dark in the forest. “Somebody’s smoke I see rising over yonder,” he said to himself. Soon into the stranger camp he came; for better or for worse, the wanderer came. Right there a large Snake was lying. “I greet you, venerable Grandsire,” the Mink hastened to exclaim. “I am glad of your happy coming, Little One. Even this long time have I been hungry. You shall go fishing for me. I am so hungry for some little fishes!” That is what the Snake said to him. So the Mink went fishing roundabout. Again it was evening, and when it grew dark nothing had he caught, for empty handed he went back. “Ee! Grandsire, nothing at all have I caught. Tomorrow, indeed, something may be caught.” Very sad the Mink felt because he got nothing at all for his fishing, for he too was hungry now. Then spoke Grandsire. “Ee! Grandson, do not be troubled, you yourself indeed I will be content to try for a meal. Go quickly now and bring a stick, hut let it be a straight stick so that your insides may not be injured more than is necessary.” Such was the manner of his speech, that Snake, for to the Mink he said that he would roast him on a spit. Then out again he went, the Mink, and wandering roundabout, he cried all over the place, for his thoughts were very sad.

“Now, indeed, I fear that I am going to die,” he thought, and he sang a song as he went about looking for a straight stick. Three times he sang it, and this was his song:

“Snake going to eat me, straight medicine.” Thus three times he sang sorrowfully, and all the time he kept thinking, “Snake is going to eat me and I must fetch him straight medicine.”2

Now from afar off the Fisher heard his younger brother’s voice crying, his younger brother Mink on whom the Snake was practicing his medicine.. “Something, indeed, troubles my younger brother now. I had better go and help him.” That is what Fisher said to himself, and he was a great magician. Stronger than the magic of Snake was Fisher’s magic. To the Mink then he came, and even before he had spoken he knew what the trouble was. “Ha! ha! younger brother, do you go quickly and get a crooked stick, the most crooked stick you can find. Tell the Old One that you can straighten it for him.” Just that he told his younger brother, whereupon that Mink went about again, and to his Grandsire Snake with a very crooked stick he came. “Grandsire,” said he, “that is all I can find.” “My Grandson, now, indeed, will your insides be sorely injured.” To which the Mink made answer. “Oh, no ! but I can straighten it, and you will rest your head right here and watch me. I will heat it at the fire and presently it will be straight.” Now he held the crooked stick, and the Snake as he watched him fell into a doze. Three times he dozed, and the third time Mink dealt him a mighty blow. Outside his wigwam then rolled that Snake. With fearful wrigglings along the ground he rolled into the depths of a valley.

Now he cried with a loud voice, that Mink, far and wide he called that all might hear : “Oh ! ye creatures ! Come ye all and eat.” Then he kept on cutting up the crooked one. Two valleys became filled up with the meat. Yea, more, a mountain of it rose between. And the creatures all came to eat, and as they ate they heard a Turtle over the hill calling, “Feed me meat,” but they just kept on eating, and when Turtle arrived, all hot and panting, there was nothing left. It was then, my hearers, that I came away.

F.G. Speck