Object Number: NA3881A, NA3881B, NA3882

Image Number: 14333, 14333a

When Penn made his first treaty with the Indians, their council fires burned at Shackamaxon, the site of Germantown. Here, according to their immemorial custom, were assembled the great chiefs of a powerful confederacy, which in its three tribal divisions, occupied the entire Delaware basin. In recognition of their admitted superiority of political rank, the members of this confederacy received from all other Algonkian tribes of the East the respectful title of “Grandfather.” They called themselves Leni Lenape, the Real People; the French called them “Loupe,” wolves, and to the English settlers they were known as the Delawares.

Their traditional history contained in their national legend, the Walum Olum, or “The Red Score,” was written in picture writing. Among the chiefs who sat around the council fires at Shackamaxon during the early colonial days was Tamenend, from whom the Tammany Society takes its name.

Under pressure of the incoming white settlers, the Leni Lenape began to leave their old homes on the Delaware about the end of the seventeenth century, working westward by way of the Susquehanna and the Allegheny to what is now Ohio and Indiana. Later, one band moved into Canada, and the main body crossed the Mississippi, to settle, after many wanderings, in Oklahoma. To-day that great historical confederacy, whose principal seats commanded the site where Philadelphia now stands, is represented by seven scattered bands, numbering in all about 1,900 souls, who preserve in Oklahoma, Ontario, Kansas and Wisconsin all that is left of the ancient traditions.

Still speaking for the most part their native language, they have given up Indian dress and modes of life, and retain only a few of their ceremonies. In dress, houses and occupations they differ little from the whites about them. Only by persuading the older people to unfold the legends to which they listened in their youth, can a picture of the old life of the tribe be obtained.

In accordance with a social system which was very general among the American Indians, the members of the three tribal divisions of the Delawares were grouped into three clans, the Turkey, the Wolf and the Turtle. These clans did not correspond to the tribal divisions, whose distinguishing names, the Munsi, the Unami and the Unalachtigo were of geographical significance. Each tribe, occupying its own territory, would have a Turkey clan, a Wolf clan and a Turtle clan.1 The members of each elan believed that they were descended from the animal whose name they bore. Each individual was born into one or the other of these clans and claimed by right of inheritance the corresponding animal as his TOTEM. Inheritance was through the mother, that is to say a child belonged to its mother’s clan irrespective of the father’s affiliations. Moreover each clan was divided into twelve smaller groups bearing such names, according to present usage, as Yellow Tree, Slipping Down and Red Paint. These smaller groups or sub-clans as we may call them for the present, were exogamic, that is to say a man might not marry within his own sub-clan, but must choose a wife from one of the other thirty-five sub-clans. His children, then, would belong, not to his own sub-clan but to the sub-clan and the clan of the mother. Among the American Indians the exogamic groups very commonly correspond to the totemic groups, but among the Delawares the custom appears to have been as described.

In the Delaware philosophy all the world was controlled by supernatural beings and all the objects and varied phenomena of nature both animate and inanimate were but the outward attributes of powerful spirits. The heavenly bodies and the blades of grass, the thunder and the wind, Man himself and the beasts of the chase had alike their actions and their destinies controlled by indwelling spirits.

Image Number: 14332

Consequently it was of the utmost importance that man should be on friendly terms with the supernatural agencies and it was equally important that he should know how to thwart the hostile designs of any spirit whose enmity he might unwittingly have provoked.

Over all this spirit world ruled Gicelamukaong, a name usually translated “Great Spirit.” He was the chief of all and dwelt in the twelfth or highest heaven.

He created everything, either with his own hands, or through his appointed agents, and all the great powers of nature were assigned to their duties by his word. He gave the four quarters of the earth and the winds that come from them to four powerful beings or ma-nit-to-wuk:—namely “Our grandfather-where-daylight-appears” (East), “Our grandmother-where-it-is-warm” (South), “Our grandfather-where-the-sun-goes-down” (West), and “Our grandfather-where-it-is-winter” or North. To the Sun and Moon, called “Elder Brothers” by the Indians he gave the duty of providing light; and to “Our Elder Brothers the Thunders,” manlike winged beings, the task of bringing rain and of protecting the people against the great horned serpents and other water monsters. “Our Mother the Earth” received the duty of carrying and feeding the people, while “Living-Solid-Face” or Mask Being was directed to take charge of all the wild creatures of the forest.

How the spirit of the unborn child kept company with its father. The spirit of the unborn child was especially attached to the father and accompanied him on his daily rounds. Therefore if he anticipated the birth of a boy, he made a tiny bow and arrows and fastened them to his person as he went about his daily occupations in order that the little spirit that followed him might have playthings calculated to keep him near the father’s person. If he imagined that a daughter would be born to him he carried in place of the bow and arrows, a little mortar and pestle such as women used for crushing corn. The father of the unborn child was apt to be less successful in hunting than other men, because the playful little spirit that followed him on his jaunts would, if toys were wanting, sometimes frighten the game at the critical moment and spoil the luck. Hence it is only natural to suppose that a prospective father often received scant encouragement to join the hunting party, and we may imagine that the occasion would bring forth plenty of jokes at his expense.

How the spirit of the new-born child was induced to remain with its human kindred. The Delawares believed that the spirit of the child gained a firm hold on this world only after a certain time had elapsed. At first the little spirit was easily coaxed away by the ghosts of the dead; hence it was necessary to make life pleasant for the children so that they might choose to remain. Precautions were also taken to lead the envious ghosts astray, as when the new-born child was wrapped in clothes previously worn by a grown-up by way of disguise, or when buckskin thongs or strips of corn husk were bound to the little wrists or ankles in the hope of persuading the ghosts that the child was bound to the earth, or when the anxious parents cut holes in the little moccasins, so that the reluctant child might say to the ghosts, “I have holes in my moccasins and cannot travel to the spirit land.” If the mother died in giving birth to her child or soon after, the little one, hearing her entreaties, was very apt to join her in the spirit world, and in such cases it was well to surround the babe with extra precautions so that it might be induced to remain for a time with those who loved it on earth.

How a child was named. The real name to be borne by a person through life was usually ascertained before birth through the medium of dreams from supernatural sources. Either the mother herself or else the father or perhaps an intimate friend would be sure to dream that such a one was coming and accordingly the name of the expected child was known before its birth. Thus if someone dreamed that Walking-with-the-trees was coming, that was the name to be given the child. If it turned out to be a girl the circumstance was at once accommodated by adding a feminine suffix and the name became Walking-with-the-trees-woman. Among the Munsi at least the name was announced at the annual ceremony.

How the Delaware Boy obtained his Guardian Spirit. About the age of ten every Delaware boy was subjected to a severe ordeal which he had to endure for a longer or shorter time according as the spirits were good to him or failed to take pity on his plight. With his face painted black, he was compelled to wander, fasting and without protection, through the forest for days at a time, exposed to all the dangers and hardships that might befall him. In the exhausted state to which this severe treatment inevitably led, he was likely to have dreams and visions, in which some benevolent spirit came to his relief and promised to be his guardian through life. With the appearance of the vision the object of the ordeal was attained and the boy might return to the ordinary way of life, but ever after, so long as he lived, the spirit that was revealed to him in his vision remained his guardian spirit and on this spirit he relied for assistance in all the affairs of life.

Image Number: 14614

Sometimes it was an animal who appeared in the vision; and the Crow, the Owl or the Wolf might become the guardian of the boy, or again it was the Sun or the Thunders or the Fire Ball or the Spirits of the Dead who came to him in his extremity, and promised to be his guardian. In any case the compact was inviolable and a peculiar and sacred relationship was thus established between the individual and some object in the world about him, or else an invisible spirit of the spirit world.

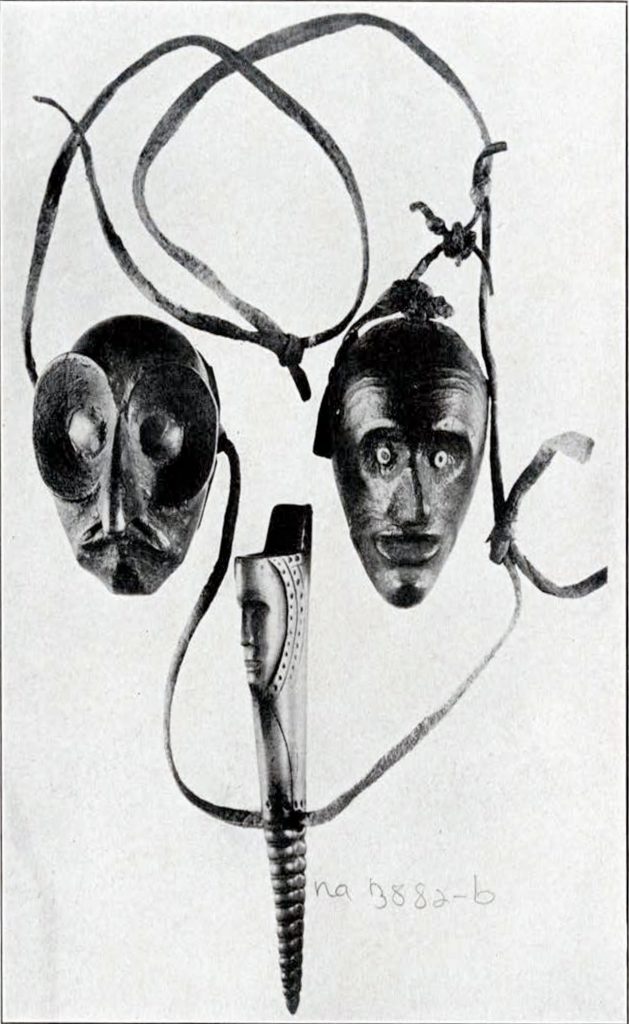

Charms and Amulets. Often, by way of a token, the guardian spirit would communicate to the object of its care some sacred charm by which the presence of the protecting power was rendered visible and especially potent. In these communications received in dreams, the boy or man was often told to make a little image either of the guardian spirit itself or of some object whose magical properties were vouched for. To this class belongs two little wooden masks and the face carved upon the powder charge made from the tip of an antler, all shown in Fig. 32. Such charms were worn upon the person and believed to bring good luck.

Image Number: 14335

Living Solid-Face. This being was, in the beginning, a personal guardian spirit which came later to be a kind of a tribal divinity. Tradition has it that three boys, fasting in the forest. saw a grotesque, man-like, furry creature riding a deer. This curious being, whose great moon-like face was painted one side black and the other red, told the boys that he was the guardian of all the animals and that he had come to their rescue and would help them as long as they lived. Some years later, because the people had grown careless and forgot to keep up the annual ceremony in which their visions were related, a long series of earthquakes ensued. Then Solid-Face appeared to one of the three boys, now grown to manhood, and explained the cause of these calamities. “Let the tribe resume the old rites in honor of the Guardian Spirits,” he said, “and the earthquakes will cease.” He then directed the young man to carve a wooden mask to represent his face and to provide a bear-skin suit to represent his body and to wear these at the ceremony. “When you put on that mask,” he said, “you will represent me and you will have my

Image Number: 141806a

power.” Thereupon the earthquakes ceased, and since that time Solid-Face was always seen at the annual ceremonies, while every spring a special dance was held in his honor.

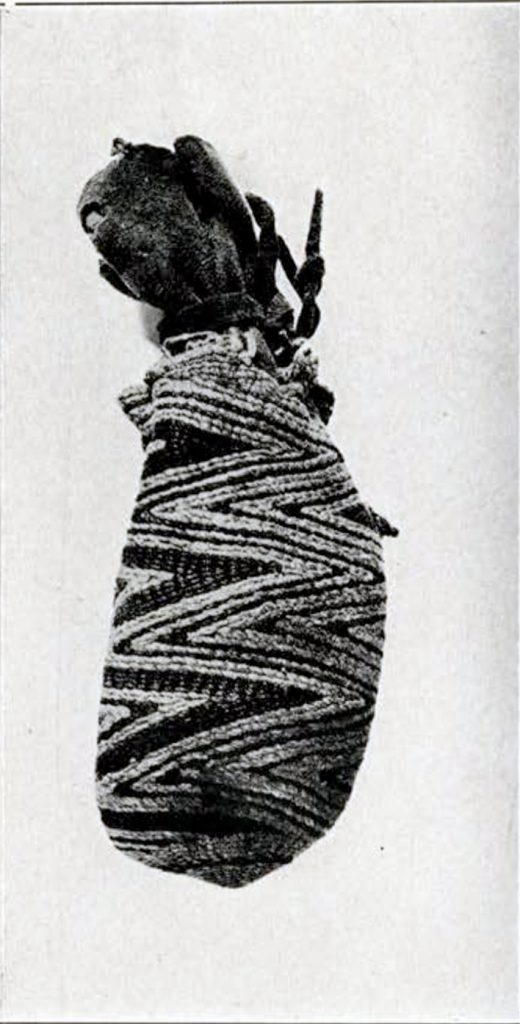

The Rain Maker. Once upon a time on the shores of the Big Water Where Daylight Appears, certain heroes captured the great horned serpent that lives in the depths of the sea and, while they held him captive, scraped some of the scales from his back and placed them in a little pouch woven from Indian hemp, with symbolical designs representing the lightning (Fig. 33). There is enmity between the Thunders and the great horned serpent who cannot show his head above the waters without provoking the wrath of the Thunders who immediately gather to attack him with their bolts of lightning. Therefore, when the scales taken from the back of the serpent, were exposed on a rock, beside the sea, or on the shore of a lake or stream, thunder clouds would immediately gather and the cornfields would presently be refreshed by rain. The owner of the charm must remove it before the first rain drops fell or he was in danger of being struck by lightning.

The Annual Ceremony. The vision of the Guardian Spirit and the adventures connected with that supreme event of boyhood formed the subject of songs and rythmic chants composed in later years and recited once every year at the great religious ceremony. To-day there may be seen in Oklahoma a rough wooden lodge. On the twelve posts in the interior are twelve carved faces representing the messengers of the Great Spirit. Here, in their land of exile, when the October leaves are yellow, a remnant of the Leni Lenape make their camps to celebrate within these walls of rough hewn logs their ancient rites.

The ceremonies last twelve consecutive nights. In the center of the lodge burn two great fires and round the walls on dried grass sit the assembled clans, each clan in its appointed place. On the opening night a chief addresses himself in a few words to the Great Spirit, and declaring the purpose of the gathering gives way at once to the leader of the ceremony who takes his place by the great central pillar with its two carved faces, and shaking in his hand a little turtle shell rattle to beat time, proceeds to chant in a high monotone the story of his Vision. Meantime two drummers who have taken their places before a peculiar drum made of a dry deer hide rolled up and stuffed with dried grass, take up the leader’s chant in the same tone and carry it with him to its conclusion when the dance song is begun. This the drummers sing in like manner, beating time upon the drum, while the leader, still holding the rattle, takes up the dance, circling about the fires, and followed by as many of the assembled multitude as choose to take part. When all his verses are finished, after a short intermission, the turtle-shell is passed on from hand to hand until it reaches another man whose Vision entitles him to a place in the performance and he in turn takes the lead. When the turtle has thus made the circuit of the Big House, usually along toward morning, the people pray by raising their left hands and crying the syllable “Ho-o-o” much prolonged, twelve times. The twelfth cry they say reaches the twelfth or highest heaven and is heard by the Great Spirit. Then a feast of corn mush called sappan is eaten and the meeting breaks up until the following night.

On the fourth day a band of hunters sets out to obtain venison for the feasts in the Big House, and returns on the seventh day. Before leaving, the hunters beseech the Solid-Face or Guardian of Game, impersonated by a man in bearskin costume and wooden mask painted half black and half red, to give them good luck. Solid-Face, armed with turtle-shell rattle and staff is seen from time to time about the camps as the ceremony progresses, and occasionally enters the Big House. Approximately the same ceremonies are enacted every night until the ninth, when the old ashes are carried out of the lodge through the west door, used only for this purpose, and a new fire is lighted with fire sticks. Prayer sticks to hold up when the cry “Ho-o-o” is raised are distributed this night and a pair of very old forked drum sticks each bearing a carved human face take the place of the drum sticks used before. One of these sticks is represented as male and the other female, and the two are said to symbolize worship by both men and women. The pair obtained for this Museum are said by the Delawares to have been brought from their old home in the East.

The twelfth night is given up to the women to recite their visions, and the day after about noon the worshippers file out, and forming a line facing the east, twelve times cry the prayer word “H-o-o,” which ends the ceremony. Before leaving the house the caretakers, the drummers, the speakers—everyone who has done a service to the meeting is paid, even to-day, with wampum.

M.R. Harrington

- 1It appears, however, from statements made by the Munsi that the Turtle was lacking in this division.