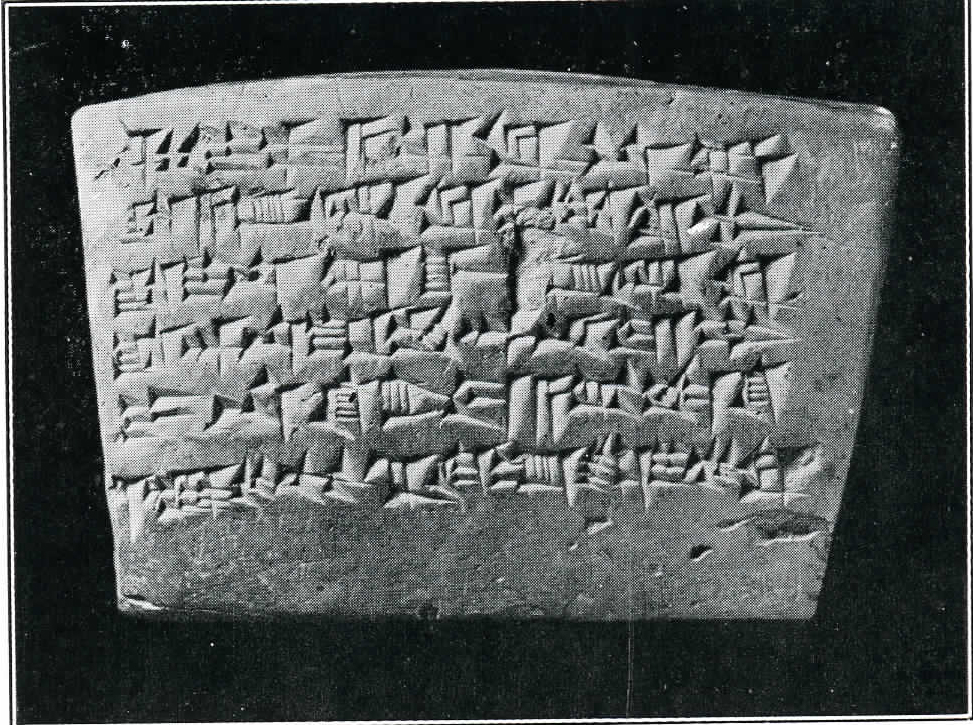

The museum possesses a Babylonian tablet of baked clay, which has been secured by purchase. Unfortunately its provenance is unknown. On the one side there is an inscription written in reversed order in the script of the Sargonic period, about 2600 B.C. The inscription, which offers no difficulties,*1 reads as follows:

Transliteration.

shar âli

da – num

shar

ba-u-la-ti

ᵈEnlil

Translation.†2

King of the city,

the mighty

king

of the subjects

of the god Ellil.

The fact that it is written in reversed order, and that the characters are raised instead of incised, suggests the idea that it was a stamp used in this early period. But the reverse of the tablet enables us to determine that it was actually made in the Neo-Babylonian period, and that it was for a different purpose, being the work of an archaeologist of that age. It contains several new words and apparently some irregularities in the case endings, but the translation appears to be as follows:

Transliteration.

sha a-sa-ar-ru pa-li-su-tim

sha i-na egalli [a-]sa-ar-ru

sha dNa-ra-am- d Sin sharru

i-na ki-ir-ba Akkaduki

ᵐNabû-zêr-lîshir dup-sar i-mu-ru

Translation.

from an exposed (?) vault (?),

which, in the palace vault (?)

of King Naram-Sin,

in the city Accad,

Nabû-zêr-lîshir, the scribe, saw.

We are at once reminded of the archaeological interest manifested by Nabonidus (555-538 B. C.), who in his passion for restoring the ancient Babylonian temples, laid stress upon his efforts in searching for the old foundation stones of the edifices and evidently took a deep interest in bringing to light facts bearing upon the history of the structures. One quotation from his inscriptions, out of several we possess, may present the pious zeal of the royal antiquarian. In his account of the restoration of the temple of Shamash at Sippar he records:

“For Shamash, the judge of heaven and earth—Ebarra, his temple in Sippar, which Nebuchadrezzar the former king had built, and whose old foundation stone he had sought and not found—that temple he had built and in forty-five years were its walls in ruins. I trembled, lost heart, fell into terror, and my face changed its appearance. Bringing Shamash out of the temple and settling him in another house, I tore down that temple and sought its old foundation stone. Eighteen cubits deep I excavated and the foundation stone of Narâm-Sin, son of Sargon, which for 3200 years no king before me had found—this stone was shown to me by Shamash the great lord of the temple Ebarra, the abode of his heart’s desire.” And he proceeds to tell how on a day appointed by the god he covered up again the cornerstone with all kinds of precious stuff, gold silver, rare woods, the stone requiring no adjustment, as it had not moved an inch from its place.*3

This inscription would indicate that the great temple-builder Nebuchadrezzar (604-562) had endeavored to discover the same foundation stone and failed in his attempt, doubtless recording his disappointment in an inscription which Nabonidus knew. The stone itself was, architecturally and religiously, the key of the building, and there was all urgency that it should be located and found to be in true position. This extreme regard for the stone illustrates Isaiah’s word (Is. 28, 16) : “Behold, I lay in Zion for a foundation a stone, a tried stone, a precious cornerstone of sure foundation.” Narâm-Sin, whose foundation stone Nabonidus found, was the son of the Sargon of our brick-squeeze.

Now Nabonidus must have employed the services of what we may call a College of Royal Antiquarians, whose members brought all their archaeological lore to bear upon the king’s undertakings. The contract literature shows that a scribe named Nabû-zêr-lîshir lived in this period and it is quite possible that we have the work of the same scribe before us. Being a member, doubtless, of the royal staff when the palace or temple of Narâm-Sin (about 2650 B. C.) in Accad was being excavated preparatory to the restorations, a stone object of some kind, perhaps in dolorite, containing the inscription of Sargon, who was the father of Naram-Sin, was found. Being only a representative of those under whose patronage the work was being conducted, he contented himself with a replica of the inscription instead of taking the object itself. Fortunately, this interesting impression of the original has been preserved for us.

It should be noted also that although the replica was found in Accad, the capital of the land in the Sargonic period, Ellil, the lord of lands, whose sanctuary was at Nippur, figures in the inscription as the deity par excellence of the ruler for whom the object was inscribed.

A. T. CLAY.

1 * The one side of the tablet was translated some years ago, see B. E., Ser. D, I, p. 517.↪

2 † The reading Shar-ga-ni shar dui instead of Sharganisharri, as maintained by the writer in the appendix to Amurru, the Home of the Northern Semites, has recently been confirmed by aka discovery of the name written Shar-ru-ki-in, Schell. Comptes Rendus, 1911, p. 606.↪

3 * Schrader, Keilinschr. Bibliothek, iii, pt. 2, p. 103 f.↪