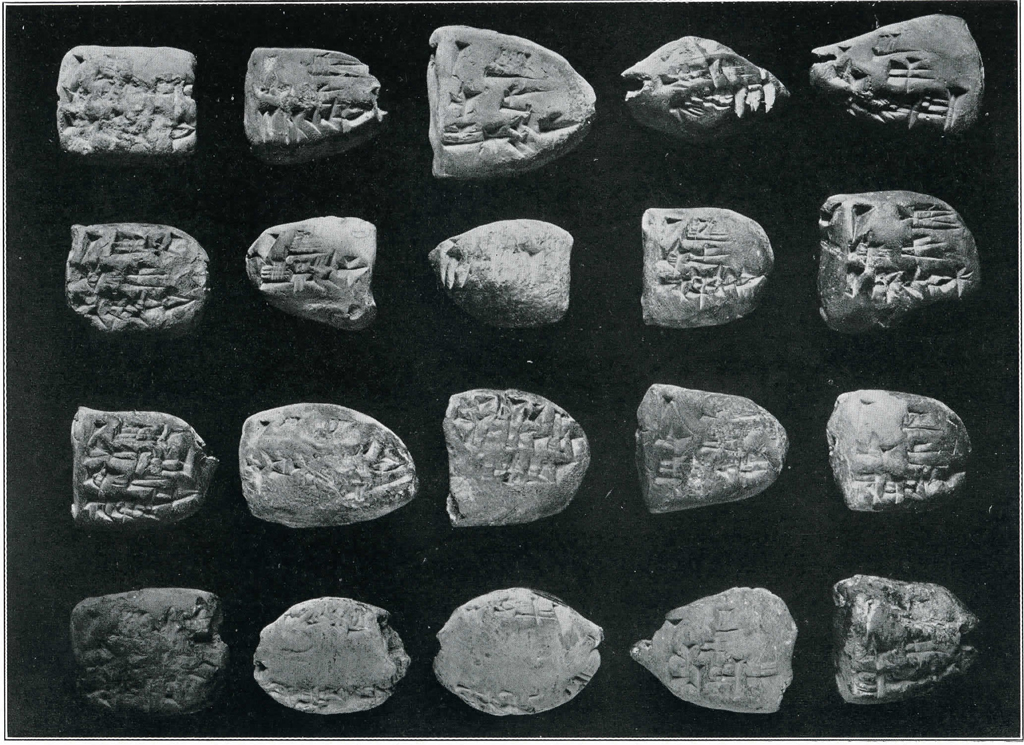

As clay was the common writing material among the Babylonians, it is quite possible to duplicate among the thousands of tablets from the Mesopotamian Valley every use known in connection with our writing material. In the large number of temple records, published from all periods of Babylonian history, practically all our legal and commercial transactions can be duplicated, e. g., records of loans, payments, receipts, contracts, deeds, etc. Of special interest, in connection with the cuneiform material excavated at Nippur, are the duplicates of the common, present day paper or cardboard tag and label.

Clay labels or tags, baked and unbaked, so far as the material at hand gives evidence, are found chiefly in connection with temple records. On the one hand there are those which were put on the revenues received, in kind, at the temple storehouses; and on the other those which apparently were used to tag live stock placed in the keeping of official caretakers or shepherds.

The former generally were lumps of clay pressed, in different shapes, upon the knot of the cord tying the object or goods to be tagged. The hole passes along the main axis of the label and clearly shows the imprint of the cord. This suggests that in all probability the cord was made of fibers or rushes tied together usually with a straight, though in several cases a slightly twisted, strand. On the outside edges of the clay are plainly seen the finger markings of the scribe. This group generally enumerates the articles tagged, the individual sending them, by whom received, the month and the year. Others merely state the goods were received (mu-du), or delivered (zi-ga), and the date. Almost all have the impression of the scribe’s seal. These last statements are based more particularly on labels coming from Drehem and Djioha.

Tags, on the other hand, are either triangular or shield shaped and flat. A hole passes through each corner, and though much smaller than is the case in the former, yet the imprint is of the same character. These contain no seal impressions. The inscription mentions the kind of animal, and the name of the shepherd to whose care it was entrusted.

The purpose or use of the label evidently was twofold. By its attachment to the goods it stated the amount, whence and by whom received. This was a sufficient note to enable the scribe to later credit them to the proper individual. Among the records of the Cassite Dynasty are receipts of tithes and revenues from the outlying districts of Nippur. The Telloh records mention TU-USH-GAL officials. These probably were revenue officers, who, as agents of the temple, collected the taxes. The revenues, collected in these outlying districts, were sent to the temple to be deposited in its storehouse. On their receipt the scribe in charge apparently attached the label with the necessary statement, and so the steward had no trouble in keeping his accounts of receipts, which were as necessary as those of his expenditures. Later the label was detached and burned along with other tablets, and then preserved as a record, in fact a receipt of the transaction. In this way the label, like many little notes found among the temple records, can be likened to the modern daybook entry from which the monthly and annual accounts, of which we have record, were made.

The purpose of the tag in the case of live stock was to designate ownership. Though no labels or tags have yet been found among the Cassite records, yet some of the inventories of animals, as well as of those placed in the care of individuals, are most interesting and interpretative in this connection. One of these tablets (Vide: Babylonian Expedition, Vol. XIV, No. 48) records the conditions upon which live stock was farmed out, and stipulates what returns were expected from the individual. Another tablet (Vide: Babylonian Expedition, Vol. XV, No. 199) is an inventory of cattle which were in the care of shepherds in certain towns. Among the records from Telloh and Drehem are numerous similar inventories. Some of these state the number of animals entrusted to an individual (Vide: Langdon, Archives of Drehem, No. 61). Others are round-ups of flocks, usually giving the number present (gub-ba-an) and the number that are missing (lal-ni-an) (Vide: Barton, Haverford Library Collection, part II, No. 34). In the light of such records, the use of the tag seems evident and intelligible. Tags quite likely were also used in connection with bags of flour and grain. In such cases they simply give the amount, and at times the date.

The following four inscriptions illustrate the general character of these tags.

- One large kid of Awilum.

- One sheep of the shepherd Ribam-ili.

- One lamb of Uzi-el.

- One goat of the shepherd Ahanuta.

These are animal tags with the names of their shepherds.

The following is a label for wool from a shepherd:

One talent and six mans of wool for the weaving woman.

dSin-mu-sha-lim, the shepherd.

The 30th day of the month Shebatum, the year when Ammizaduga, the King, (dug) the Canal Ammi-zaduga.

The bulk of the objects of this class from Nippur are animal tags, and belong to the time of the First Dynasty of Babylon, 2000 B. C. Scattered through the published material are labels of other periods, e. g., Lugal-anda, Dynasty of Ur, and the Assyrian period. A large number are in the Yale Collection, and in the library of Mr. Morgan, which in connection with others in various collections, I have fully treated, and expect to publish under the title: “Cuneiform Labels and Tags of the Third Millennium B.C.”

C. E. KEISER.