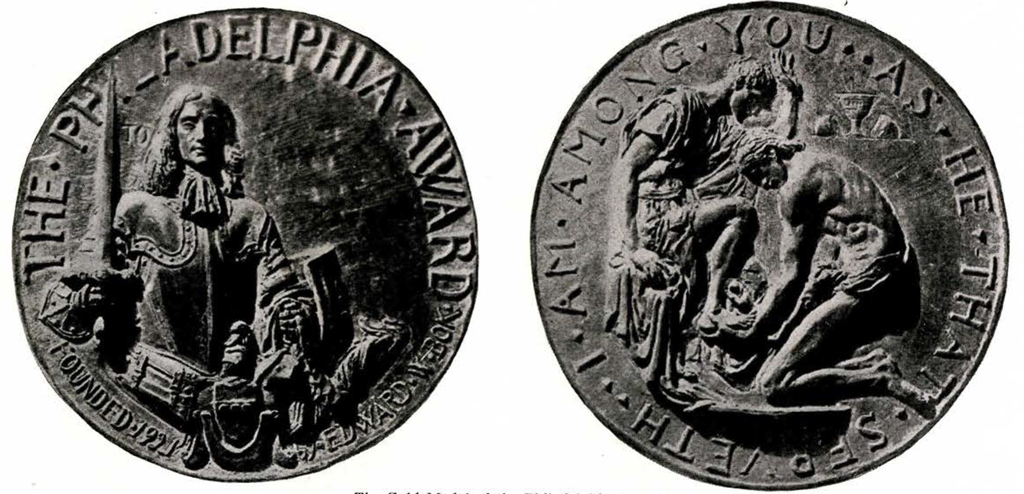

The Philadelphia Award was founded in 1921 by Mr. Edward W. Bak. The Award is conferred upon the man or woman living in Philadelphia, its suburbs or vicinity, who, in the judgment of the Board of Trustees of the Award, shall in the past year have performed or brought to its culmination an act or contributed a service calculated to advance the best and largest interests of Philadelphia.

The Honorable George W. Norris

Ladies and Gentlemen:—The word “service” is one which is very much upon people’s lips these days, but I sometimes wonder just how accurate a conception we have of its meaning. What I thought was a very admirable definition of it that I saw recently was this: “Service is labor baptized and anointed and consecrated to high ends.” That definition is well typified in the design to be found upon one of the old Roman coins, of an ox standing between a plough and an altar, ready for labor or for sacrifice. It is service rendered in that spirit, no matter in what field, that the founder of the Philadelphia Award meant should be recognized and given a visible and public token of appreciation. And it is with an understanding of that spirit that we are assembled here tonight to witness the fourth annual presentation of the Award.

A year ago I found myself in an embarrassing position. Senator Pepper, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Award, was unavoidably detained in Washington, and I had to apologize to you as best I could for his absence, and attempt the impossible task of substituting for him. Some wag remarked at the time that his absence in Washington was due to the fact that he was pouring water on the troubled oil. But this year both you and I are more fortunate. As the newspapers have already advised you, the Senate has confirmed an attorney general and has concluded its twenty-year deliberation upon the Isle of Pines Treaty, so it has adjourned and the Senator is with us. That being so, my only function is to open this meeting, to express the gratification of the Board of Governors and the members of the Philadelphia Forum in being allowed to participate in such an interesting occasion, and to ask the Senator to take his place as permanent chairman of the evening.

The Honorable George Wharton Pepper

Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen:—I think it is no disparagement to my colleagues in the Senate of the United States to say that upon my return to Philadelphia and in the presence of an audience like this, I feel that I am successfully breaking into the best society.

The founder of the Philadelphia Award had in mind not merely service as interpreted by Mr. Norris in his opening, but service rendered for this community and through this community to the Nation. And because the service is rendered to Philadelphia, our meeting is incomplete in the absence of the official head of the city who is, Mr. Chairman, detained in Harrisburg, where he is happily discharging the duty of taking part in the presentation to the people of the state of that venerable charter under which the liberties were guaranteed which we, the descendants of the fathers, have ever since enjoyed. We miss him, not merely because his official capacity requires that he should be with us, but we miss him because we e fortunate enough to have in the office of Mayor one who has himself rendered nation wide and notable service in the cause of promoting human happiness and welfare. In his absence, ladies and gentlemen, let us resolve ourselves into a committee of the whole and do some collective thinking respecting the significance of the award which is to be announced tonight. Our collective thinking is likely to be the happier and the more useful if we call upon somebody to direct our thinking and lead us along sane lines. I know no one who can do this better than the man who is himself the head of a great educational institution, the man who is engaged in shaping the educational policies of one of Philadelphia’s greatest institutions, the University of Pennsylvania—a man who is the father of a great student body of fifteen thousand men and women. Suppose we call upon him to permit us to enroll ourselves for a time as part of his great student body, call upon him to interpret the Award for us and direct our thoughts along the lines the founder would fain have us follow.

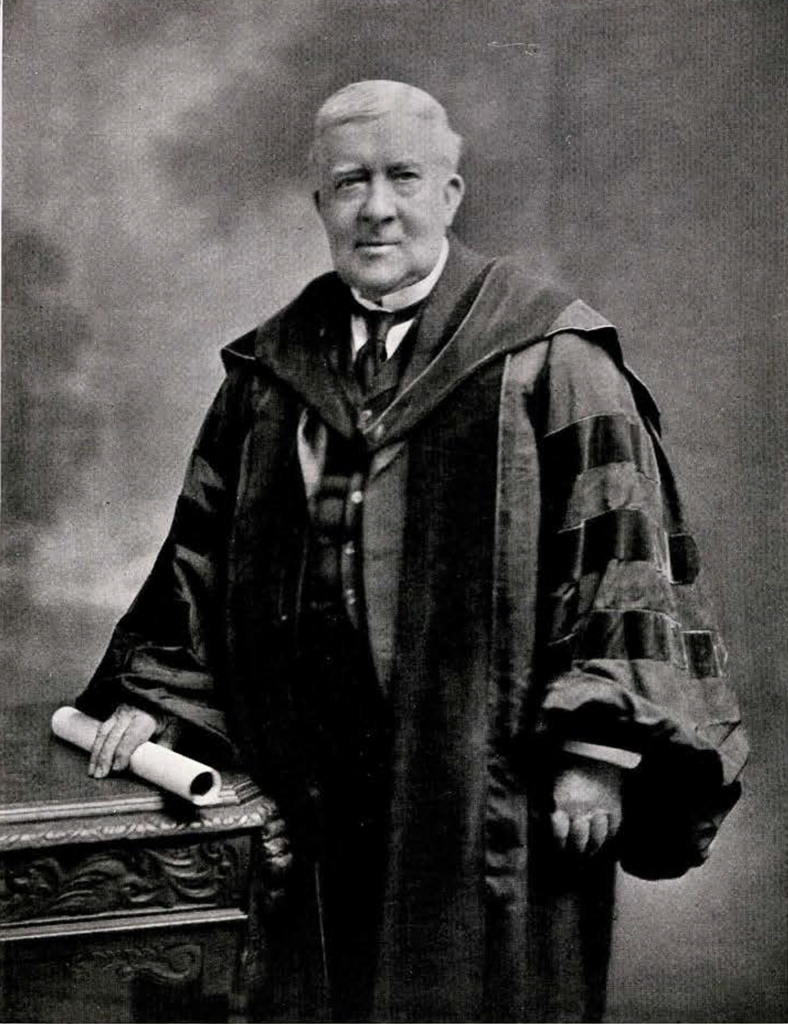

I have great pleasure in presenting to this audience the President of the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Josiah H. Penniman.

Josiah Harmar Penniman, LL.D.

Members and Governing Board of the Forum, Ladies and Gentlemen :—The Philadelphia Award, under whose auspices we have met tonight, exists in two worlds—the world of the material, and the world of the spirit; the world of the real—actual, and the world of the ideal. It is in no sense a prize to be striven for, though its existence in this community is a constant reminder that the good of the people should actuate the lives of the citizens. The prize cannot be given to anyone who has worked for his own selfish interests. It is always given to one who has been characterized by his entire devotion to the service of others.

The greatest poets have all written of a better world that is to be. The people look forward to a time when existing evils shall have been done away. Youth looks forward, the present generation looks forward, all who believe in the immortality of the human soul look forward. The man who for whatever reason retires from business or from the practice of a profession looks forward, it may be and usually is to the enlarging of his own soul. It is never with the thought of spending his remaining years looking back over the path he has trodden, for there is always a pathway ahead that he must tread. No man with his faculties unimpaired derives pleasure except from the use of those faculties. No other view of philosophy of life, I believe, is worthy of the man or woman who has achieved nobly.

Failures in the past of either the nation, the community or the individual are warnings but they terrify none. The look is always forward, to the avoidance of errors of the past and to achievements greater than any hitherto accomplished. For the great examples of the works of men of long ago, we are profoundly thankful. They show what man has done, and what man has done man can do. The work of great geniuses and creative artists of the past have been vouchsafed to us as a precious heritage. We waste no time in worshiping the past simply because it is the past, although we wonder at the magnificence of the achievements of those who lived millenniums before our own day. It is the present moment that gives us our opportunities, and it is the use of the present moment that determines our future. It is the example of the achievement of the great ones of the earth who utilized what were to them their present moments that has given us our view of the greatness of life itself. Those who have created for us in stone as buildings or statues or monuments of whatever kind have enriched our lives, but the building or the statue, material though it may seem, is after all only an idea in a mind which through marvelous artistic skill has become immortalized in marble. The great pictures of the past are likewise ideas, conceptions which first existed in the mind and soul of the artist and had no object in existence at all. Great pictures by the aid of skill, by the aid of the pigment and the canvas, have become immortalized and the idea of the artist goes marching down through the centuries through his works that have come to us.

The great books of the world are but the embodiment in language of thoughts of men by which they were inspired and through their writings have inspired us, for they are the great storehouses of the world’s learning through which we inherit the knowledge that men have accumulated up to our day and have handed on to us, with no effort of our own for our use.

There is a difference between a power plant and a storage battery. We may, if our souls are open to the impressions and influences of art and literature and science, have our own lives enriched and become ourselves the centers of energy. But there is a difference. We can be the author of an idea or the source of energy and power, or merely the echo of an idea or the transmitter of the energy of others. The power plant which creates or rather transforms into some particular useful form the energy which has existed from the beginning makes possible the storage battery which stores it up merely in order that we may use it when, as and where we desire. The man of genius creates ideas and is the source of energy which he usually also applies. The man of talent usually, great though his talent may be, applies the energy that others have given to him.

It requires faith, hope and love to put at the disposal of other men those ideas upon which the happiness of the world depends, and without which life itself would be a dreary thing.

Giving alms to be seen of men is to be condemned, although those who do it have their reward. The widow’s mite is the gift that is remembered, for she gave all that she had and was doubtless sorry that she could not give more.

In every instance the Philadelphia Award has been given to a person who has borne and is yet bearing the burdens of others and therein finds the height of human happiness. Burdens are borne for others who cannot bear them for themselves, but who need greatly some aid, some sympathy, some sharing of the weight of the burden on the part of others to help them in the accomplishing of the purposes they recognize as the purposes of their own lives. To ease in some way or in some measure the burdens of others; to awaken in them a realization of the possibilities of life, is one of the greatest tasks as it is also one of the greatest opportunities that is placed before any man or any woman. To help others to the realization of their own ideals, imperfectly seen it may be, but still ideals toward which they are striving with all the energies of which they are capable, is likewise one of the greatest tasks and one of the greatest opportunities that are vouchsafed to man.

To open a window of the soul on a side from which may be seen a view, beautiful, surpassingly beautiful, but hitherto unknown until that window of the soul has been opened; if we can do that for a fellow man, we have made one of the greatest contributions that a man can make to the happiness of another individual or to a community.

It is the opening of the eyes of the blind, the unstopping of the ears of the deaf, the restoring to them, the giving to them, of the great world of beauty which with blinded eyes they cannot see; or opening to them the marvelous beauties of music and of the sounds of nature which with ears stopped they are deaf to. There are various obligations that rest upon us as individuals and collectively as a community and no obligation is such that aid in fulfilling it may not be found as the expression in action of a leader of men, for the leader inspires those who follow and they follow because they have been so inspired. Maeterlink said in a familiar passage, in substance, that the life of the peasant of Europe today is different from what it would have been had Plato and Platinus, of whom mayhap the peasant never heard, not lived. George Eliot said in ” Middle-march” “the fact that things are as they are with you and me is due in large part to the lives of those who wrote sincerely in their day and now rest often in unmarked graves.” What we hear, what inspires our soul may be but the echo of a sound struck long ago. The quality of the echo, nay the very coming to us of the echo, is dependent upon two things—one is the quality of the original sound, and the other, the quality of the surface from which it reverberates.

To change my figure—energy makes itself felt by us first and necessarily because there is a source of that energy without which it could not reach us and then because there is a medium of transmission through which that energy has been conveyed to us. We may be ourselves, and in the case of geniuses of which there are not many in any generation or any century, we may be ourselves the cause of the sound or the source of the energy by which the life of another is vitalized. It is then that our own souls and minds sound a musical note of our lives that reaches others, the quality of which is peculiarly ours, and which differentiates from every other one who strikes that same note in the same pitch, as the note of a violin differs from the note of an organ or flute. It may be the same note, but there is something individual about it that characterizes it as coming from that person and no other.

If either factor in the creation of an echo is changed or modified the result is also changed. If the original sound were different, the echo would be different. If the reflecting surface were different, the reflection would be different, so that things have come to us from the remote past through a definite line of intermediaries it may be, but things come to us from the genius of the present direct and fresh from the soul of the great. If either factor in the transmission of energy is changed, we receive only a part and not the whole of the energy that should come to us. Some men and some women are like the great resonators or loud speakers of which we hear today. The sound which reaches them is multiplied a thousand fold and through their intermediation reaches millions, it may be.

There are souls that create and there are souls that transmit. Some may transmit not a single sound with its overtones, but may blend it with other harmonious notes or an occasional deliberate and artistic discord so that the original sound when heard becomes a part of a complex. The note is there, it can be heard, but the harmony of the chord may make a deeper appeal to the soul which recognizes harmony as a higher thing than melody.

Life is complex. The contents of the mind and the workings of the mind are complex. They are subject to all kinds of influences. The fact that things as they are, not as we would like to have them, if dwelt upon morbidly as they are by some, render unutterable anguish to those souls, but the thought that things may be changed as a result of the efforts of even an individual or a small group, magnetizing, calling into action a great group or whole community, is a great thought. It is inspiring. Inspiration to work full of faith toward the bringing into harmony, if not into unison, things as they are and our ideal of them as they ought to be furnishes intellectual life with a motive urging it on, and a goal toward which it runs.

Faith in the possibility of realizing our own ideals, even though it be disturbed as it often is by doubts as to our own ability to achieve, nevertheless sustains the inspiration by a mighty challenge to our manhood.

The interpreter of art or of music or of philosophy, the teacher of what is known to those who know it not, the observation of new facts and phenomena and the correlation and the interpretation of those facts and phenomena contributes to the highest intellectual and spiritual happiness of the world. It is not given to all to discover or even to interpret, but it is within the reach of all to teach others what has been received. He that is able not only to create but also to interpret and then to impart to others the results of his creation and of his interpretation of phenomena and facts places the world under great obligations. He may do all of these things, yea, frequently does do all these things unconsciously, as Emerson said, “Nor knowest thou what argument thy life to thy neighbor’s creed hath lent, all are needed by each one; nothing is fair or good alone.”

The problems of the modern city come within the purview of what I have been saying, and the citizen who makes no pretensions to genius or to greatness, does his daily task with mind and heart open to what is going on around him may be by that very fact adding to our happiness and comfort and mind, adding to our faith in life and its great purposes.

My mother, on a number of occasions, remarked to me as we were traveling through foreign lands and saw people at work at various tasks, “I am profoundly impressed,” she said, “by the lives of those who do the hard work and the drudgery of the world.”

The strategy of the greatest general amounts to nothing without the men in the ranks to put it into action, while the men in the ranks are as sheep without a shepherd unless they have leaders who may develop from their own numbers.

We honor leaders when they are successful. We sympathize with them when they are not successful. We reward with medals, with citations, with promotions, the private in the ranks who has performed a notable deed.

No evidence of spiritual forces as the real ruler of the world came to us as a lesson from the great war comparable, I believe, to the thought that in practically every land there is now a shrine enfolding the body of an unknown soldier who typifies to his nation the spirit and the achievement of millions, and who in return, though nameless, receives the homage of a grateful people. Such idealism, though present in a sense cannot characterize the presentation of the Philadelphia Award, someone may say, but is he correct in saying that? Shall we not later, when we hear the name of that woman or that man to whom the award is given this year realize that in an individual, whoever it may be, actually exists the power of a general in command, the power of the private in the ranks, to do his share in the carrying out the strategy of the great thinker.

The recipient of the Philadelphia Award is of necessity one who planned wisely and wrought successfully, not for selfish purposes, not for personal glory, but because, with such qualities of soul and mind and heart, it was not possible for him or her to do otherwise—for us the service was rendered. We are among the thousands that have had sight given to us, have had our ears unstopped, the windows of our souls opened to the greatness of the contribution to life that may be made by one person.

The Honorable George Wharton Pepper

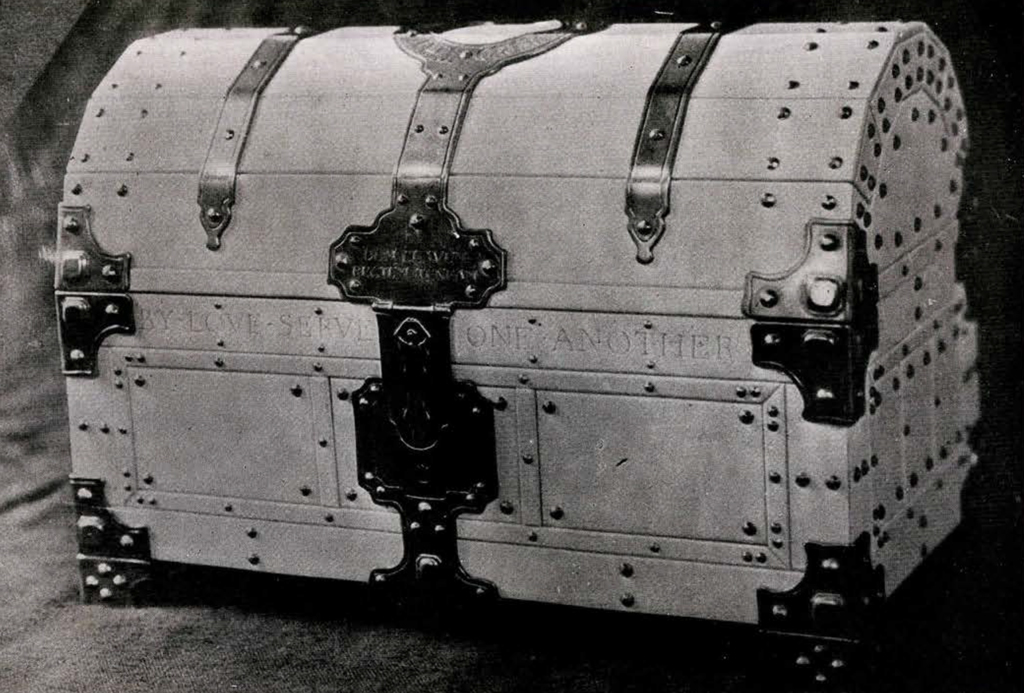

I hold in my hands a casket of exquisite workmanship. When it is opened, it will be found to contain a medal of gold, a medium for the payment of the award to the recipient, and a scroll upon which the name of the recipient is inscribed. Whose is the name? Is it the name of man or woman? Three years ago the award was bestowed upon one who had set the name of Philadelphia to music and sent it echoing around the world—Leopold Stokowski. Two years ago the choice fell upon one, a man of God, who has proved to be guide, philosopher and friend to more young people in this community than any other single person, and last year the happy choice was made of one who had, unobtrusively and unselfishly, placed within the reach of thousands the means of self expression through art. Who shall it be this year?

Somehow I have an inkling that this year again it is a man and not a woman—but what manner of man? What has been the quality of his life? Of course, it has been a life of service. Of course it must be true that he has spent of himself and of his substance freely for the citizens of this community and for others more remote. Has he done this at large or through the medium of a single institution?

It is always more or less dreary to recite things in retrospect. Instead, therefore, of standing in 1925 and looking backward, go back with me in thought to a time many years ago when this man was young, and let’s look forward and forecast the order of his life.

It is a hot June day in 1862, sixty three years ago, and the Class of ’62 is holding its commencement exercises. I know how those boys in the top gallery feel when they hear about the class of ’62. When I say I graduated from this stage thirty eight years ago this year, I am sure that they will feel they are watching the moving picture of ” The Lost World,” seeing brontosaurs and dinosaurs with queer shapes strutting across the stage which it would be more decent for them to vacate. But here is a hot morning in June in 1862, and the stage is set for the commencement exercises. I look at that little group of men and I recognize the features of some of them. I see my own father in that class; I see my stepfather; I see my uncle, Dr. William Pepper; I see our dearly beloved and lamented friend, John Cadwalader. I see many men destined to become notable in the life of this community. And there is a student graduating at the head of his class who is delivering in Greek the commencement oration. Look forward over the course of his life. In three years he is to win his master’s degree. A dozen more and you will find him a trustee of his Alma Mater and a chairman of her most important committees. In the years that follow, you find him identified, unobtrusively, with the continuous growth of the institution. Thirty-two years after his graduation, you can see him in prospect taking account of the great estate to which the University by that time has attained. You will find him reckoning the assets of the University in terms of five millions of dollars. You will find him counting over two thousand students upon her roll. You will find him reckoning the teaching force at close to two hundred; and then you find him the year later, in 1895, honored by election as Provost of the institution. And there ensues one of the most remarkable periods of unselfish, devoted and fruitful service that this country has known—a period of sixteen years, at the end of which, when he voluntarily in 1910 lays down the cares of office, you find that he has placed upon the shelves of the library eight volumes for every one that he found there; you will find that he reckoned a student body double in size of that which was there when he entered upon his duties; a teaching force twice as great in numbers and many times as great in efficiency. You will find that he himself erected sixty three buildings; that he has trebled the acreage of his Alma Mater; that her resources have increased more than three fold; that he has enhanced her prestige among the institutions of learning, and placed Philadelphia in the fore front of centers of American education.

And then, quietly and unobtrusively, having left no inheritance of debt on any building or in any expense account, you find him turning to a different department of service of his Alma Mater, giving himself with unremitting effort to the upbuilding and development of a great free Museum of science and art, carrying on the work of a distinguished predecessor and so insuring that Philadelphia will have in perpetuity a treasure house destined to be comparable to the British Museum in London, and the Metropolitan Museum in New York; and, friends, not only this, but he, during the all but fifty years of unselfish service to you and to me, through his Alma Mater, this man has himself raised by personal solicitation and in cash just a little short of twelve millions of dollars. Have you ever tried to raise a thousand?

And all of it done under the inspiration of a love of learning and loyalty to the institution that breathed into his nostrils the breath of the academic life. And he himself for the advancement of learning and the enlargement of the boundaries of knowledge has created the George L. Harrison Foundation which today amounts to more than a million of dollars and is known and valued all over the world.

And during all this time this fellow citizen of ours, this unobtrusive man, whose course we have fore-shadowed from that hot day in June of 1862, this unobtrusive man has done all these things without pecuniary compensation or reward even during the sixteen years of his provostship—not a penny of compensation for the work done, and a hundred cents out of every dollar in twelve millions has gone undiminished to the cause to which it and he were alike dedicated. But, my friends, it is easy for me to stand here and recite these achievements, but those of you who know what life is; those of you who know against what obstacles one must contend in the development of a great institution; those of you who know what fire of enthusiasm and resistless energy it takes to open the imaginations of those whom you would have partake with you in the great task that you set yourself, will know that in a few words I am telling you the story of a great life. This is the record of one who has wrought mightily from love of learning and from mere loyalty to the institution that nurtured him. Here is a man who has lived into his mature life, through to his three score years and ten, and then beyond; and instead of finding that his strength is then but labor and sorrow, he is working patiently and persistently onward and upward to the end that Philadelphia may be a happier place to live in; to the end that we may radiate far and find the gladsome light of learning.

My friends, it is the name of this man that is inscribed in the scroll within this casket; it is the name of this man that is inscribed on this beautiful medal of gold; it is the name of this man that I now pronounce to you, in virtue of the authority conferred upon me by the trustees, and on behalf of the founder as the worthy recipient of the Philadelphia Award in 1925—a Doctor of Laws, a friend of man —Charles Custis Harrison.

Charles Custis Harrison, LL.D.

Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen :—Naturally my first thanks are due to Mr. Bok, who cares nothing for money except to make the best use of it, and by whom the Philadelphia Award was made solely possible. After that, and with deep sincerity, to the Presiding Officer, to the Provost of the University of Pennsylvania, to the President of the Philadelphia Award, Senator Pepper, who has just made the presentation address, and last, but not least, to the Committee upon the Philadelphia Award, by whom the present choice was made.

Of course, I can say nothing in addition to the words which Senator Pepper has so generously spoken, other than to accept gratefully the decision of the committee, the words which have been spoken here tonight, and the evidences of the award which just have been handed to me.

It would be quite impossible for me, happily to accept this great award without full recognition of the indebtedness which I have owed for many years to others, without whose constant care and devotion whatever may have been accomplished during the last fifty years would have been out of the question.

This indebtedness is due—first of all to my father, who as he was one of the best, so he was one of the ablest of men, helping me in season and out of season, and turning my thoughts in certain directions with the best help of his advice and judgment from day to day.

But even mare than to him, I owe that debt of gratitude to her, who, though no longer with me, stood by my side in every public work which I undertook during the entire fifty two years of our married life together. Living in a certain sense in the past, one of the chief enjoyments of the privilege which has now been bestowed upon me is to be able to name to this audience my father and my wife, to both of whom my daily thoughts always turn, and who will be remembered with even greater fervor of affection from this time forward.

I do not know that I can add any further words, except that it may be a pleasant thought to this great audience to know that I am one of a large group whose name I bear, who for generations, even from the founding of the city, have been Philadelphians.

I beg again and finally to thank you all for your generosity, your courtesy and your great kindness.

Comments of the Philadelphia Press on the Philadelphia Award

A Well Merited Award

Dr. Charles Custis Harrison’s devoted and disinterested service to the cause of education and to the community of which he has been one of the brightest ornaments has been of such a character that no distinction, no especial honor, could enhance the esteem in which he is held by his fellow citizens. Nevertheless, the conferring upon him of the “Philadelphia Award” for service “calculated to advance the best and largest interests of Philadelphia” will be hailed everywhere as a well merited recognition, wisely and justly bestowed.

For Dr. Harrison’s contribution, in personal service and in material aid, to the University of Pennsylvania and to the University Museum cannot be measured in dollars and cents, nor even by the growth of these institutions in usefulness and public estimation. It was Dr. Harrison’s personal example of untiring and selfless devotion to the best interests of the college and the museum, the inspiration of his guiding influence, which won for them a support and a co-operation of immeasurable value and importance. The record of that service is written in stone and steel, it is true, for coming generations to see and emulate, but it is engraved more deeply still in the hearts and memories of his contemporaries and in the impress which it has made on the permanent policy of the University. —The Public Ledger.

Merited Honor to a Useful Philadelphian

All those who are familiar with the life and the civic activities of Charles Custis Harrison will agree that no mistake was made when he had conferred upon him the Bok Award. The scroll of fame, the gold medal and the $10,000 check which go to this distinguished educator and philanthropist only serve to emphasize the esteem in which he has been held by his fellow citizens.

The reasons given for bestowing this particular award upon Dr. Harrison are starting work on a new University Museum plan; completing a new wing of the museum at a cost of $500,000; bringing the unrivaled collection of Oriental art, valued at $2,000,000, to the museum; financing the expedition of the museum in connection with the British Museum at Ur of the Chaldees, and his many charitable gifts. But the work that he did during the past twelve months only added to the good he has been doing all of his life. While he was the Provost of the University he raised more than $11,000,000 for the institution; he completed forty seven buildings on the grounds; he fathered Franklin Field; he raised $4,000,000 for the University Museum; he gave $500,000 for the George Lieb Foundation; he collected $250,000 for the memorial chapel at Valley Forge, and for half a century he has been a leader in good movements.

It is well to speak of these things during the lifetime of such a busy and useful member of society. His personal modesty and unostentatious life have only been equaled by his activity and aggressiveness in helping to advance everything likely to be desirable for the city. We have had other men of this type in this community, but it is doubtful if any one has been able to accomplish more than Dr. Harrison during his long span of life. When he passes away from this earthly sphere he will leave many monuments to himself, all of them conceived in an unselfish spirit. His heart has been in the University of Pennsylvania and naturally most of his work has been in the interest of that great institution, but those who know him best are aware that he has not permitted his benefactions to halt there.

It is characteristic of the man that he should at once decide to present the cash award to some worthy object. The first and last thought in connection with the incident is that the judges have honored themselves and the City of Philadelphia in honoring Charles Custis Harrison. —The Philadelphia Inquirer.

A Well Deserved Distinction

He would be captious indeed who would find any ground for criticism in the honor conferred upon Dr. Charles Custis Harrison in being selected for the Philadelphia Award of 1925. No Philadelphian would seem more deserving of it, for in his long and most useful life no one has served his native city more unselfishly, more modestly and more generously. To his labors as Provost the University of Pennsylvania owes much of its remarkable growth of the past quarter century, and when he laid down that burden it was only to take up that imposed upon him by the claims of the University Museum. To him more than to any other one person the rapid development of that admirable institution is largely due, and it is a good thing that Philadelphians should be made acquainted with his great service in this direction during the past year.

It has always been characteristic of Dr. Harrison that he has subordinated himself in his many lines of civic activity, and for this reason the general public has a faint conception of how useful and valuable a citizen he has been. It is gratifying, therefore, to see that the directors of the Philadelphia Award have not overlooked this modest gentleman, but have recognized his great services in the only way possible to him. Still active in his eighties, there are more years of usefulness open to the recipient. His remarkable record makes it certain that he will continue to spend himself in the public service until the very end. —The Philadelphia Record.

A Builder Honored

A man to whom a great university is a monument needs no prize for his good deeds—except in so far as the awarding of the prize concentrates attention on the man himself and increases the number of persons who know and appreciate his life work.

The Philadelphia Award cannot make Dr. Charles Custis Harrison greater than he has been. But it can make his fellow citizens greater by emphasizing his example. Doctor Harrison has been a builder. His forebears have been builders. This year’s prize winner, as provost of the University of Pennsylvania, completed forty seven University buildings. He raised $11,000,000 for the University. He has made the University Museum one of the great institutions of its kind in the world. He has made possible the erection of a divinity school and he has made countless benefactions to charity.

The city is very glad that Doctor Harrison publicly and officially has been designated the great builder he has always been. And the city hopes his active life is not nearly over and that the man himself, as well as his shining deeds, will remain through many a helpful year. —The North American.