At the beginning of November, 1924, the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the University Museum resumed work for the third season at Ur of the Chaldees. Mr. C. Leonard Woolley remained in charge and Dr. Leon Legrain, Curator of the Babylonian Section of the University Museum, joined him as second in command and as specialist in Babylonian antiquities. Mr. J. Linnell is the third member of the expedition. Mr. Woolley’s reports are submitted at the end of each month and are regularly released to the press of this country and of Great Britain simultaneously. It is Mr. Woolley’s practice to prepare two separate sets of reports, one very full as to detail and technical in language and the other with less detail and in language that avoids technicalities. The reports or November, December, January and February have been received. The less technical versions prepared by Mr. Woolley for general readers are given here with a few of the photographs made by the Expedition. On the 8th of March the work of the Expedition came to a close for the season and the members were travelling by way of Baghdad and Aleppo to London and to Philadelphia.

EDITOR.

Image Number: 183128

December 6, 1924.

The Joint Expedition restarted its work at Ur on the first of November and can now report a month’s further progress in the unearthing of the monuments of the buried city of Abraham. Last season we had cleared the Ziggurat, the huge brick mass which, a second tower of Babel, dominated the whole town, but though we had dug down to its foundations we had found that these stood high above the level of the plain and must themselves rest upon an artificial platform. This year our main task was to trace this platform and to discover what were the surroundings of a ziggurat, whether it was an isolated structure or whether it formed a part of a more considerable complex.

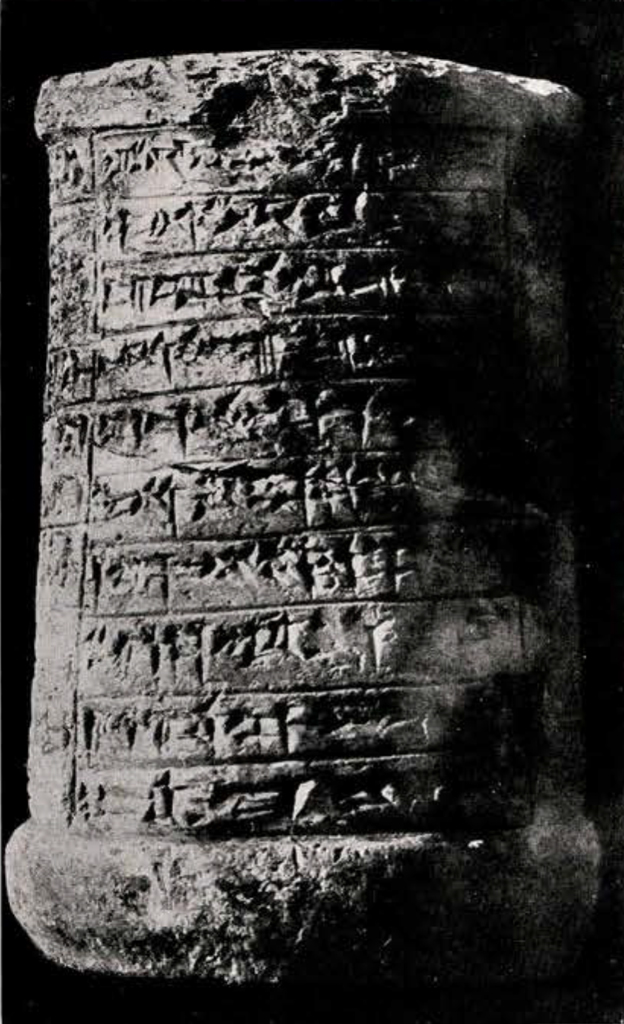

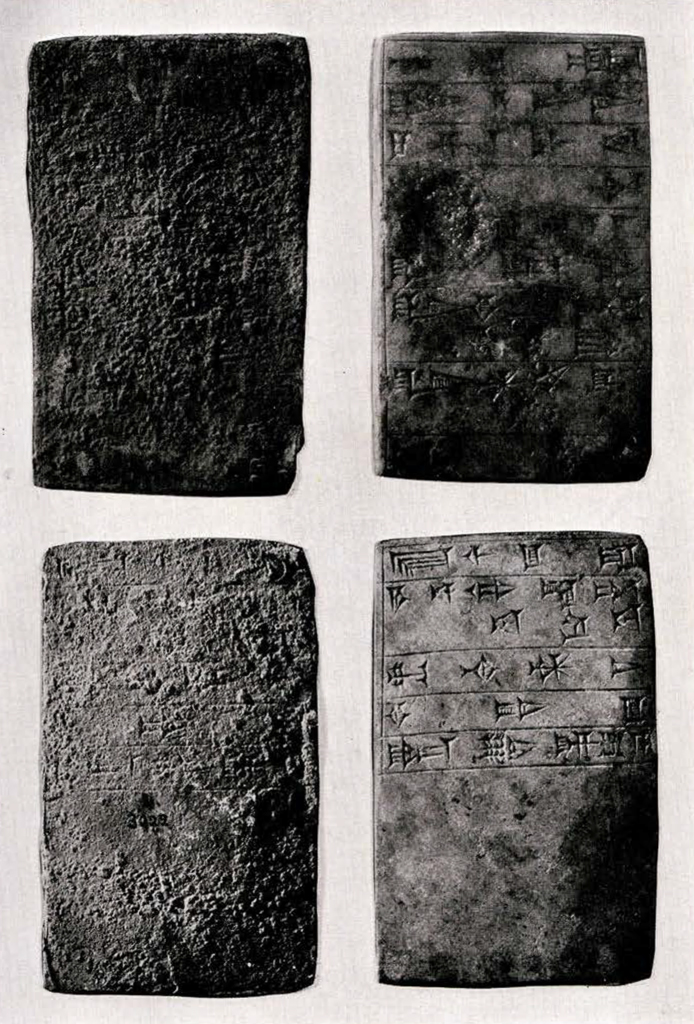

Work was begun to the northwest of the tower, between it and the wall of the sacred enclosure which we had planned in our first season. Almost at once we came upon ruined buildings, but these proved to be of late date, the living quarters and store rooms of the priests who in the Persian period still clung to the perhaps already ruined temple and collected from the faithful few the tithes of grain and oil which in scanty measure were paid to the once supreme Moon God. Below these stretched the wide courtyard laid out by Nabonidus, last King of Babylon, when he restored the ancient ziggurat, an open space covering the whole area between the Tower and the enclosing wall, which we now for the first time recognised as belonging to the late Babylonian period. Under the courtyard floor came all that was left of a great range of buildings dating from the sixteenth century B. c., and under these again still older walls of shrines put up, as the inscribed clay cones from their foundations sheaved, by the kings of Isin and Larsa who ruled Ur two thousand years before Christ: it was obvious that in early times there had been round the ziggurat shrines, store houses and priestly dwellings which more or less masked its bulk and were placed here not for architectural effect but for practical purposes, to fulfil the complicated needs of what was not a church but the palace of the reigning god who had had about him a whole crowd of ministers and administrators devoted to his comfort and dignity but also directing his material estates. How various their functions might be was illustrated by the contents of a small hoard of clay tablets found in another building, part of the business archives of the temple of E-nun-mah; here were receipts for corn and oil, butter and milk and cheese, brought in by the farmers and the diarymen to their overlord the Moon god, and here too notes of the issues of the same—rations to the temple servants, a half bottle of the best oil for the head of a man who was sick, and all the petty routine of a big estate agency. For the smallest item there was a permanent record in the shape of a clay tablet duly witnessed and dated, for these old Sumerians were a business like people, and every month the complete list of tithes paid was drawn out on sheets of clay nearly a foot square ruled like the pages of a modern ledger. With all these goods to store and with the offices for their administration plenty of space was required, and it is not surprising to find that the subsidiary buildings attached to the god’s house cover a wide area of ground.

Image Number: 8751a

But it was when we had dug down through the stratum representing the period of the Larsa kings that we found what was the primary object of our search, the terrace wall of Ur-Engur, the original builder of the great ziggurat itself ; it was a massive wall, buttressed and sloping sharply inwards as befits a retaining wall of a platform, built of unbaked brick, and in rows at regular intervals there were driven into its face nail shaped cones of fired clay, their round heads forming a pattern on the wall, their stems inscribed with the name of the king and the dedication of his building to the god of the Moon. For the first time these inscribed cones had been found in position and their real use made clear;—for the first time we can get some idea of what the ziggurat looked like in its original setting when in 2300 B. c. Ur-Engur “built a terrace and filled it with refined clay and set the House in the midst of it.”

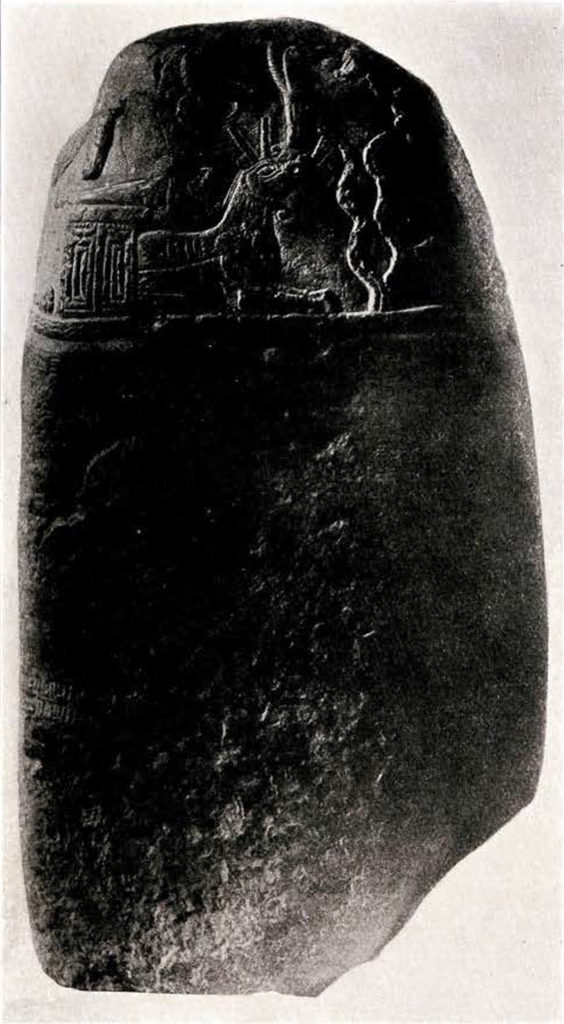

Excavations on the southeast side of the ziggurat, close to the temple of E-nun-mah which we cleared two years ago, have proved not less interesting. A fairly high mound of rubbish covered a building which had been excavated by Mr. Taylor in 1854; Taylor’s summary publication did not encourage hopes of any important finds to be made at least on the upper levels, but for the planning of the city it was necessary to expose anew what he had unearthed and thereafter to dig down to the presumably more fruitful strata below. Actually the top building which Taylor had partially dug has proved to be more than worth while. There are two main chambers with walls of burnt brick of a surprising thickness, quite incommensurate with the apparent insignificance of what was supposed to be a small house of late date; the two principal doors are very wide, and from the first room two small arched doorways give access to chambers built of mud brick lying on either side of the main rectangle. The whole thing is on a small scale, and it was surprising to find on the brick stamps in its walls that it was entitled “E-dub-lal-mah,” the Hall of Justice; but when the plan was put on to paper the real nature of it became clear, for the plan was that of a triple gateway of which the back door had been blocked up by a later cross wall, and the mud-brick chambers alongside had been built in or over the ruins of the massive double wall in which the gate tower had originally stood. Doubtless of old the judges “sat in the gate to give judgment,” and when the remodelling of the sacred area and the abandonment of this part of its wall line made the gate as such useless, the gate tower was preserved to fulfil its traditional function and a new wall was built behind to close it in and turn it into a regular justice hall.

Image Number: 8751b

Later discoveries, even on the higher level, confirmed what the plan had shewn. Fresh brick inscriptions speak of the gate and the fortifications and the terrace to which the gateway led up; and by one of the arched doors was found a magnificent green stone gate-socket shaped as a serpent with a hollow in the top of its head wherein the pivot of the door hinge turned, on the base of which Sinbalatsu-ikbi, Assyrian governor of Ur about 650 B. c. had caused to be written a long inscription recording his restoration of the fallen tower and his setting up of new gates made of costly foreign woods, bronze and silver and gold.

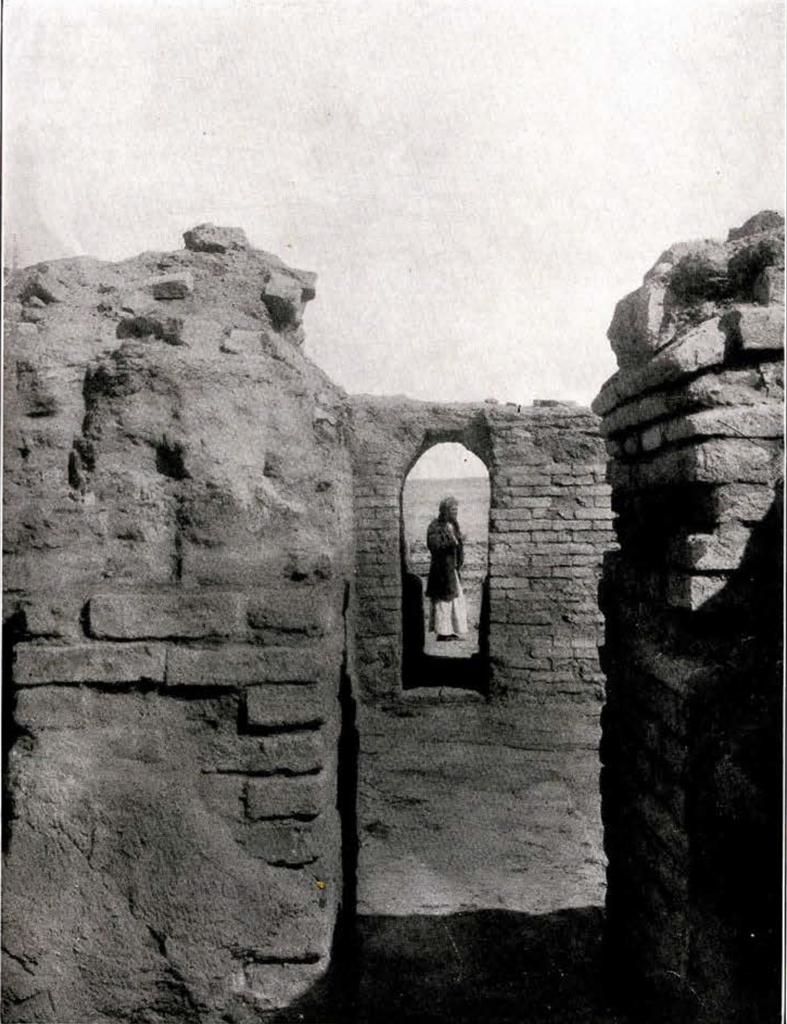

We have yet far down to go before we bring to light the original gate and discover who first set it up: at present we are dealing with the building in its last phase. We know that by 2000 B. C. it had to be repaired by Ishme-dagan king of Larsa, and that again in 1600 B. C. it was in a ruinous state, even its foundations giving way, so that they had to be strengthened and a protecting wall built up against them by Kuri-galzu the Kassite king; nearly a thousand years later Sinbalatsu-ikbi rebuilt it, and still it served as the great gate of the Temenos, the gate, probably, which spanned the Sacred Way, and through its portals on feast days passed the processions going up to the central terrace from which rose the towering bulk of the ziggurat. But what stands above ground today represents the Hall of Justice in late Babylonian times; it may well have been Nebuchadnezzar who laid out the spacious court in front of its doors, and the pavements of the side chambers bear the stamp of Nabonidus, the last of the Babylonian kings (550 B. c.) ; a huge mass of brickwork blocks the old exit. Yet the walls which stand eight to ten feet high above the late pavement are the old walls which Kuri-galzu restored, and even the arch, preserved intact over the narrow doorway, may date back to his time and be the earliest example known of an arch used on the facade of a building as an architectural feature.

December 31, 1924.

During December the Joint Expedition has been carrying on work on both the sites described in my last report. In that I announced the discovery of the mud brick wall built by Ur-Engur in 2300 B. C. to support the terrace on which stood his great ziggurat tower, a buttressed wall in the brickwork of which were inserted clay cones stamped with the king’s name: now we have been able to work out the problems of an unusually tangled site and reconstruct the history of what was the religious centre of the city of Ur.

Image Number: 190389

Ur-Engur’s terrace covers yet older buildings of which our deepest trench has failed to produce any material trace, though the filling was rich in fragments of early pottery and there came to light one delightful little shell plaque engraved with the full length figures of two royal or divine persons which must date back to at least three thousand years before Christ. Probably the actual buildings of that period are buried beneath the mass of the ziggurat, where they are safe from the explorer’s disturbing hands. On the terrace, at the ziggurat’s foot, Ur-Engur erected the House of Nannar the Moon God; it was a walled courtyard with buildings along two sides; of these one, a small but apparently lofty chamber, was probably the shrine wherein stood the statue of the god; the others probably served as storerooms for the offerings made in his honour: it was perhaps due to some tradition dating back to primitive times that the walls of the more important rooms were of crude mud brick, the simplest and oldest building material of the land.

Image Number: 8883

The Third Dynasty of Ur, which Ur-Engur founded, lasted for less than two centuries and then, about the time of Abraham, collapsed as a result of the disastrous wars with Elam. The enemy put Ur to the sack, they overthrew the House of Nannar, and the statue of Nannar itself was carried off in triumph to the Persian highlands. The traces of their destruction are clear to this day in the ruins of the old shrine. Ur did not soon recover, and the hegemony of Mesopotamia passed to other hands, but the new kings of the cities of Isin and Larsa looked with favour on the town of their predecessor. Gimil-Ilishu of Isin brought back the statue of Nannar from Anshan and reinstalled it at Ur, and the son of king Ishme-Dagan, En-an-atum, who was high priest of Nannar at Ur, started to repair the buildings on Ur-Engur’s terrace. Most of the Larsa kings who succeeded him did something to restore the same shrine—one whole range of chambers was rebuilt by Sin-Idinnam—but these rulers were none too powerful or wealthy, and their work is of a poor type, a mere patching of the ruins. A change comes with Warad-Sin, one of the last and greatest kings of Larsa. He built much at Ur, and on the particular site with which we are now dealing he threw out from the old terrace front a fortress-tower of solid mud brick faced with burnt brickwork, containing staircases and a sally port to the low ground at the terrace foot, the whole eloquent of those troubled days and of the king’s constant wars with Babylon whose rulers disputed with him the overlordship of Mesopotamia. When, after his time, Babylon won the rubber, Ur suffered once more from sack, and thereafter from long neglect; the buildings of the Larsa period sank into decay. It was not till about 1600 B. c. that a Babylonian king turned his attention to the ancient city; but then Kuri-Galzu the Kassite took its repair seriously in hand. Already one of the Larsa kings had refaced Ur-Engur’s terrace wall with burnt brick; Kuri-Galzu added to this a fresh facing, thereby still further widening the terrace, and above it he rebuilt one complete range of rooms, following closely on the lines of the former buildings, and the other range, which may have been in better state, he must have repaired, though the actual ruins shew no trace of his work. He also restored Warad-Sin’s fort.

Up to this time the successive restorers had observed with reasonable piety the traditions of the site, so that the terrace of Kuri-Galzu was not altogether unlike that of the earliest builder; and up to this time our history of the work done on the site is sure. About Ur-Engur’s walls, scanty though their relics are, there is no doubt; the minor kings of Isin and Lars left us their inscriptions on bricks in their walls or on scattered foundation cones, and in the case of the fortress of Warad-Sin we found a whole row of his great nail-shaped clay cones embedded in the brickwork just as they had been put there by the builders; Kuri-Galzu too was not sparing in the use of bricks inscribed with his name. But after his time a change took place. In the course of the next thousand years the buildings collapsed and their debris fell down from the terrace edge and filled in the low ground at its foot, and when at last a new builder came on the scene that scene was so different that not only the old ground plans but even the old ground levels had been obliterated. A nameless ruler, perhaps Sin-balatsu-ikbi, who was Assyrian governor of Ur in the seventh century B. c., laid his floors above and beyond the original terrace walls and used for his work bricks of all dates pulled out from the ruins of forgotten shrines; it was shoddy work, and today its remains look shoddier yet, for the paved floors go in waves and billows as the hidden walls below support them or the loose packed rubbish has given way, and the broken walls gape and lean at indecent angles, while the patchwork of material skewing the mutilated names of kings whose reigns were a thousand years and more apart condemns a decadent age.

Lastly came the Neo-Babylonian kings, Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus, and found again a ruin so complete that they were enabled if not forced to remodel the site. Round the whole sacred area of the city they built their great double wall, enclosing the ziggurat in its western angle and reaching out to the northwest beyond the vanished terraces and beyond Sin-balatsu-ikbi’s buildings, but returning again to link up with the solid mass of Warad-Sin’s fortress, which they restored anew. In the west corner of this temenos wall was set a massive fort of mud brick. From Warad-Sin’s fort another double wall ran southeast, in front of the Ziggurat steps, to the ancient E-dublal-makh, the old Gate tower and Hall of Justice, which now became part of the fortifications, and thence it ran southwest to meet the Temenos wall at a point where a fourth fort seems to have completed the scheme. Thus the Ziggurat was girded about with a wall of defence, standing in the centre of a rectangular enclosure having a fortress tower at each corner. All this had no relation to the old plan, but though the former buildings were buried deeply under the floor of the court that stretched between the Ziggurat and the new walls, yet the tradition must have survived that hereabouts should be the House of Nannar—and Naboni-dus was not the man to disregard tradition. When then we find in the angle between the flights of stairs leading up the Ziggurat a series of chambers the asphalte of whose floors is laid over bricks stamped with the name of Nabonidus, we can only conclude that here, not knowing where the original shrine stood, he set up his new House of the Moon God.

I said that the Neo-Babylonian kings came last, but in truth there were others after them. In the days of Cambyses the Persian, when the temples of Ur were falling into decay and men were turning themselves to other gods, in the shelter of Nabonidus’ court an impoverished priesthood built with mud and broken bricks crooked hovels for their own shelter and stores and granaries for such tithes as the faithful might yet offer. Today their ramshackle walls stand separated by only a few feet of rubble from the top of the terrace wall of Ur-Engur: in the tangle of walls that intersects those few feet is recorded the story of two thousand years of a great city’s life.

Image Number: 9111

January 31, 1925.

Throughout January, in spite of a cold which at times felt almost Arctic, the Joint Expedition has carried on the work of excavation at Ur, and the results, though not sensational, have certainly been interesting. As usual, we have been digging on two separate sites at once, thus making full use of our two foremen, Hamoudi and Khalil, and creating a healthy spirit of rivalry between the gangs.

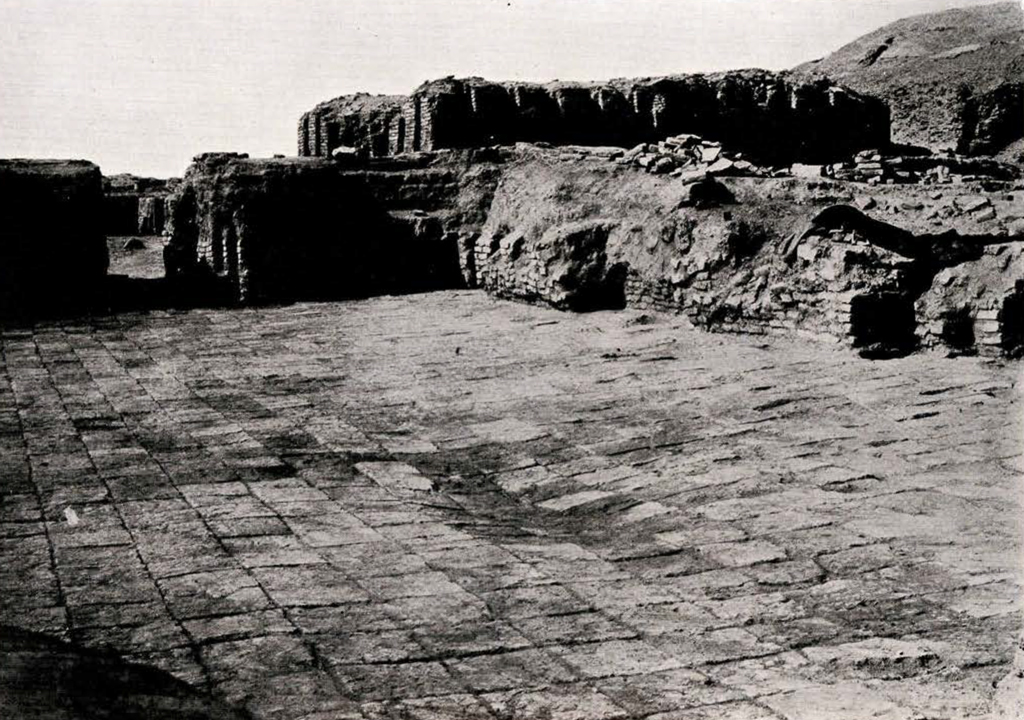

In my last report I described the discovery of the convent built by king Nabonidus for his daughter Bel-Shalti-Nannar, the High Priestess of Ur; we have now gone further with this work and laid bare the whole building—or at least so much of it as is preserved—and find that it comprises within its walls regular houses with private courts and rooms as well as the work chambers and offices which we first encountered: the largest of these may well have been the quarters of the Princess herself, for the tiles of the floors are stamped with her father’s name and the phrase “the House of the High Priestess.” Owing to the ruined state of the building its clearance did not take very long, and early in the month we started to dig down to the lower levels, and below the Convent we found another large complex of buildings first put up about 2000 B. C. by the rulers of Larsa to whom Ur was then subject, and later restored by Kuri-Galzu the Kassite king of Babylon; now virtually the whole of this has been excavated, and with it the great paved court which lies between it and the Hall of Justice described by me in a former report. It is always rather disappointing to look down into a hole and to be told that what you see at the bottom was once a palace or a temple: today at Ur one can wander from room to room between walls eight feet high and come out into the wide spaces of the court whose trim pavement of kiln baked bricks was laid down more than three thousand years ago and above one the fluted walls of the Justice Hall which, though shorn of most of their height, still dominate the buildings round. At the foot of the pedestal on which it is raised are the remains of the brick platform where the priest stood and poured his libations when the great gates of the temple were flung open in the morning; the Arab workmen in their long cloaks going up the steps that lead to the temple door might belong to any age; and it is easy to forget that so many centuries have passed, leaving only ruins, and to imagine for the moment that all is as it was, that the bare walls are clothed again with plates of silver and brass and that in his inner shrine Nannar is still enthroned.

All about the courtyard were fragments of stone, the wreck of statues smashed to atoms by some enemy, and it is tantalising to recover on such the inscriptions which tell that these were the offerings or even the portrait figures of early kings of the city; but the destroyers have done their work only too well, and bits of the same sculpture may be found hundreds of yards apart, and though all are sedulously collected there is small chance of reconstructing anything entire. In the complex of rooms beyond the court there were found above and below the brick floors hoards of clay tablets dealing with the business side of the Temple administration and spewing that this building was one of the industrial centres of the Nannar shrine where the women and children attached to the god’s service were employed on such tasks as weaving the wool which the tenant farmers of the Temple domains brought in as rent and tithes. In a former letter I gave some account of the contents of the many tablets of all sizes which have been labouriously extracted from the ground and baked and brushed and mended by Dr. Legrain; their complete translation is necessarily a question of some time, but already he has been able to extract from them enough to give a new and very human interest to the ruined chambers whose mere ground plan might have told us so little. As it is, a copper smelter’s furnace takes on a new importance when it illustrates a text recording the amounts of metal paid in to the temple by the coppersmiths of the city, and even the long storerooms become less commonplace when one has the tally of their contents.

An unexpected discovery has been made in the south angle of the walled enclosure which Nebuchadnezzar built round the Ziggurat tower. Here I looked to find a fort such as stood in the west corner, but the walls which gradually came to light from under the heaps of ashes covering the whole area soon took a different shape, and one could recognise a temple which inscriptions on bricks and stones proved to be that of Nin-Gal, the Great Lady, wife of the Moon god of Ur. The building on which we are now engaged—for its excavation is not yet complete—occupies the whole of the south corner of E-temen-ni-il, the terrace enclosure of the Ziggurat. Most of the walls are of crude mud brick of miserably bad quality, often ruined right away and where still standing to any height extraordinarily difficult to follow; my most experienced pick men have found their skill taxed to the utmost to distinguish between fallen mud rubble and brickwork so soft that one can rub it to powder with one’s finger; but the floors are of brick well laid and thickly spread with bitumen, looking like modern asphalte, and with their help all the outlines of the chambers could be traced even where the walls enclosing them had altogether perished. The temple was built, in its present form, by Sinbalatsu-ikbi, the Assyrian governor of the city (c. 650 B. c.), who always seems to have been short of cash for his building schemes and so to have employed the poorest materials; fifty years later Nebuchadnezzar added, or repaired, some of its outbuildings, and later again his grandson, Nabonidus, repaved the temple floors. The plan is the best thing about it—it is remarkably regular in its layout and really dignified in conception: from a forecourt flanked by small chambers a pylon gate gave access to the entrance chamber or pronaos: doors on either side of this led to subsidiary suites of rooms filling the angles of the temple enclosure; and from the pronaos, facing the entrance, a flight of shallow steps ran up to the naos or shrine chamber wherein on a raised base surrounded by a screen wall of burnt brick, was set the statue of the goddess. Somebody has been before us here, for the solid pavement of the shrine has been broken through, and a gold bead and fragments of gold leaf lying in the disturbed soil shew that the foundation deposit has been removed; but we have no need to give up all hope, for below the ruins of this Late Babylonian temple are those of a far earlier building of the same character, and though as yet we are busy with the upper levels only, the few trial pits that have been sunk into the lower strata have given more than promises of good results: we have inscribed door sockets of several periods, inscribed foundation tablets in black and white stone and in copper with texts of Kuri-Galzu and of Warad-Sin of Larsa (2072-2060 B. c.) and one of the earliest inscriptions yet found at Ur describing the foundation of the temple by a local governor “for the life of Utu-Hegal king of Erech ” who was suzerain of Ur before Ur-Engur won his independence and founded, about 2300 B. c., the dynasty which gave to the city its greatest prosperity and its most splendid buildings.

The season’s work of the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania comprised four months’ digging, the last month being the banner month with regard to finds, to crown the year with just that sensational discovery which had been lacking in its earlier months.

Image Number: 9350

At the end of January we were still engaged on the excavation of a temple built in honour of Nin-Gal, wife of the Moon God, by Sinbalatsu-ikbi in 650 B. c. and restored by Nebuchadnezzar and his gransdon. In February we continued this work and completed the plan of the building, clearing what was left of its courtyard and the small chambers round it and finding the well in the court. A curious feature was that in the well head there were numerous bricks stamped with the name of Sinbalatsu-ikbi but having in their text variants which showed that the Assyrian governor had put up shrines and statues of no less than eight deities other than Nin-Gal herself ; the principal sanctuary where the great brick statue base was found in position must have been surrounded by a whole row of minor chapels like the side chapels of a modern church in France or Italy. Having planned and photographed the late temple we proceeded to destroy it, for in its miserable condition it was not a monument worth preserving and certainly there were older ruins below waiting to be dug out. The destruction was soon repaid: under the sanctuary walls there stood in position, just as they had been placed two thousand five hundred years ago, thirteen baked clay cones beautifully inscribed with the Assyrian’s dedication of his work, new texts belonging to a little known ruler; and five feet below the workmen came upon the walls and paved floors of the next period. Generally the royal builders of Ur followed religiously the lines laid down by their predecessors, and each new plan is a copy of the old; but Sinbalatsu-ikbi, perhaps because he was a foreigner, had taken no account of such tradition, and the lower temple was of a different type and differently orientated from that above it. Built by Kuri-galzu in the middle of the second millennium before Christ, this House of Nin-Gal with its courts and store rooms occupied the whole space between the S. E. face of the Ziggurat tower and a paved street which ran N. E. by S. W. from the great court of E-dublal-makh to the limit of the sacred enclosure: a double doorway in a projecting gate tower formed the entry from street to temple, and immediately facing this was another similar doorway giving access to another temple on the south side of the street whose excavation we have only begun. In the filling of Kuri-galzu’s building we found the head of a small statue of a priest finely carved in black diorite, a work of about 2200 B. c., and a written monument of an earlier day, a steatite tablet recording buildings by Gudea; Gudea, who was governor of the town of Lagash about 2350 B. c., is well known from the French excavations at Tello and from the portrait statues of him now in the Louvre, but it had not been suspected that his power stretched so far afield as to include Ur. Kuri-galzu’s walls are built upon a brick pavement which may be five hundred years earlier than his time, but we shall have to dig deeply yet if we are to find here traces of the work of the patesi of Lagash.

Museum Object Number: B16676.14

Image Number: 190457

Museum Object Number: B16676.14

Image Number: 190458

For the rest, our extra funds have enabled us to clear the west corner of the courtyard and further ranges of rooms flanking E-dublal-makh, the old shrine and Court of Justice described by me in a former report. Had this work not been done in the present season it might well never have been done at all, for it is never very tempting to polish off the odd corners left over from a pervious year, especially when there is no reason to suppose that anything of value will be found; even as it was I hesitated to spend money on continuing what had been hitherto the unremunerative task of digging down through seven feet of hard soil to a brick pavement, and it was more obstinacy than anything else that made me go on. Almost the first day produced in one room a door socket of king Bur-Sin (2200 B. c.) with an inscription in 52 lines giving the history of the temple’s beginnings, a very welcome record; but it was in the western wing of the great court that the discovery was made which overshadowed all others. Here the pavement was littered with blocks and lumps and chips of limestone, ranging in size from four feet to an inch or less, some rough, others carved, some pitted and flaked with the action of salt, some as smooth and sharp as when the sculptor finished his work; and all, or nearly all, belonged to one monument, the most important yet found at Ur.

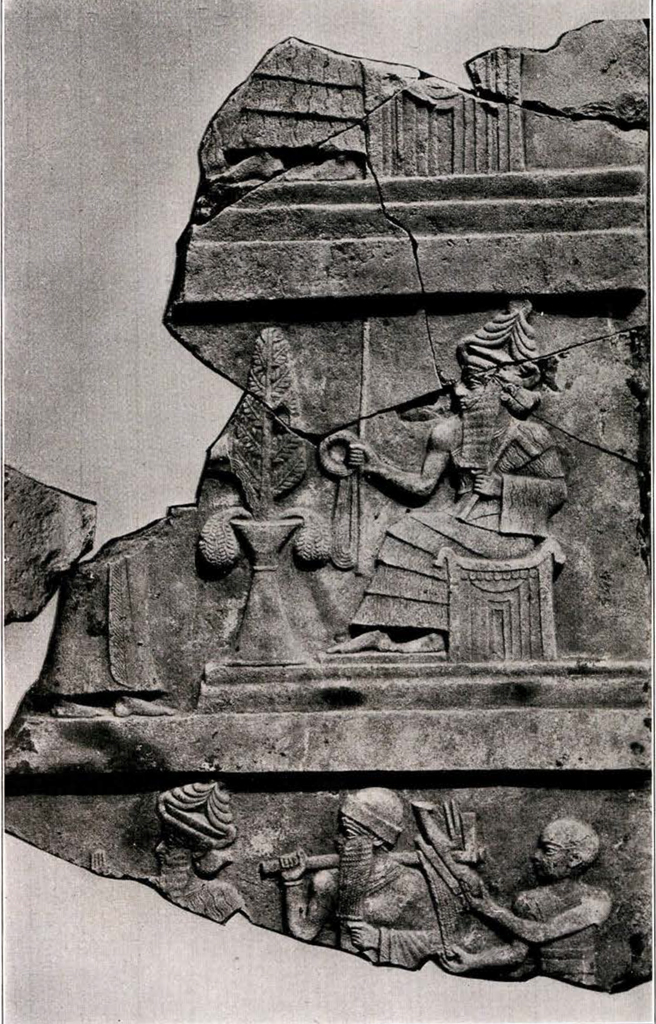

This monument was a stela or slab five feet in width and perhaps fifteen feet high, carved on both sides with a series of historical or symbolic scenes arranged in horizontal bands of unequal heights. It bore a long inscription, now fragmentary and with the king’s name missing; but here luck favoured us, for on a mere flake of stone, the drapery of a figure otherwise lost, there is inscribed the name of Ur-Engur, and we can therefore identify the author of the stela with the founder of the Third Dynasty and the builder of the Ziggurat. The fragments found by us represent only a fraction of the whole carved surface: none of the registers is complete, some have disappeared altogether, of most we have only bits, often disconnected, from which to reconstruct the design; but even so the monument ranks with the famous (and equally fragmentary) Stela of the Vultures in the Louvre as one of the two most important relics of Sumerian art known.

Museum Object Number: B16676.14

Image Number: 190460

The reliefs illustrate king Ur-Engur’s care for his people as shown by the digging of canals for the irrigation of the land, and his piety in building for the Moon God the great Ziggurat of Ur. What remains of the inscription is a list of the canals made by him, and this is illustrated by a most curious scene in the top register of the stone: the king stands in an attitude of adoration before the seated figure of the god, and above his head is an angel flying down from heaven and holding in her outstretched arms a vase from which streams of water pour out upon the ground: the scene, which appears on both sides of the stela, seems to have been repeated several times in the register, perhaps with an angel symbolising each of the principal canals. The whole conception is new to us, and the graceful figure of the angel is unique in Mesopotamian art.

Other scenes are those of sacrifice to the gods. In one, two men have thrown a bull down on its back, one grasps its forelegs and sets his foot upon the beast’s muzzle while the other stoops forward and seems to be cutting it open to examine the liver for omens; a third man has cut off the head of a he goat and, holding the body in his arms, pours out the blood from the neck before a smaller figure, perhaps the statue of a god, which stands upon a low pedestal; others pour libations of water upon a simple pillar like altar. In another scene two men are lustily beating a great drum; in another there seems to be a row of prisoners, a record probably of the king’s conquests. But most interesting of all are the pictures of the building of the Ziggurat, shown upon three registers the main fragment of which appears in my photograph. In the upper scene we have the Moon God Nannar seated upon his throne and receiving the worship of the king who pours the water of libation into a tall slender vase wherein are palm leaves and dates; a continuation of the stone gives the rest of the scene. On the left, corresponding to Nannar, is seated Nin-Gal, the Moon’s consort, and the king reappears before her making the same libation; in each case behind the king there is an attendant goddess who assists in the sacrifice. Nannar holds in his left hand a pick axe, and in his outstretched right hand the measing rod and line of the architect: here then Ur-Engur in a vision receives from the god himself the order to build him a house. In the next register, only the top left hand corner of which is preserved, one of the minor gods ushers into the presence of Nannar the king who comes to declare his readiness to obey the divine instructions; upon his shoulder he carries pick axe and basket, compasses, the ladle for the bitumen mortar, and the flat wooden trowel of the bricklayer, as if he would himself take part in the work and lay the first brick: behind him comes a shaven priest who solicitously relieves the royal shoulder of its unaccustomed load. In the register below, represented now only by small fragments, there was pictured the actual building of the Ziggurat; the background is formed by the wall of the tower, and against this are ladders up which go men carrying on their heads baskets of mortar. Fortunately the surface of the stone is in these fragments wonderfully preserved, the carving sharp and fresh, and we need not draw upon our imagination to do justice to the skill of the unknown artist who in 2300 B.C. designed and wrought this splendid monument: the simple treatment of the drapery, the restrained faithfulness of the rendering of the body muscles, the delicacy of the features of the different faces, show the hand of a real master: And if we have here in such excellent state a magnificent example of the art of the time, we have also a historical document whose appeal is not less direct. The Ziggurat of Ur is the most imposing relic left in Mesopotamia of the land’s early grandeur; now chance has given to us the pictorial record of its building and a contemporary portrait of the great ruler who was inspired to build it.

Museum Object Number: B16676.14

Image Number: 190461

Museum Object Number: B16676.14

Image Number: 190459