The excavations that the Joint Expedition of the University Museum and the British Museum is conducting at Ur have already let us into some of the secrets of the builders of that ancient city. The building trade, which is a very old one, has had a continuous development for not less than 6000 years, measured from the oldest foundations that already have been uncovered at -Ur to the present time. It is interesting, therefore, to compare the methods of those very early masters of the trade with the newest and most up to date devices. It will be found that the differences are not always so great as might be supposed.

Image Numbers: 150421, 8703

In taking stock of the performance of the Urites in architecture and building, certain general conditions come at once under observation. One of these is the advanced state of ruin that has overtaken all the buildings and the very incomplete nature of the architectural detail presented to the eye in the excavations. Another is the universal use of bricks for building. Stone is almost entirely absent even in the greatest buildings, for the reason that no suitable stone occurs in the formation of the Mesopotamian plain. The architectural remains of Mesopotamia therefore have an effect different from those of Egypt, Syria, Palestine and Persia, where stone for building purposes was abundant. This difference also, in part, explains the more advanced ruin in which the Mesopotamian buildings are found and in general the more complete obliteration of architectural outlines. These outlines have in large measure to be restored by the excavators from observations made among the ruins and the rubbish in which the buildings are involved. Brick does not last or resist the action of the elements so well as the harder stones. At Ur there is little left of the buildings except the rubbish heaps in which the foundations are found. These foundations as they emerge in the excavations afford the plan on which reconstructions may be developed or at least attempted. The actual structures remaining in position can be illustrated by photographs, and as these structural remnants contain many lessons concerning the builders’ trade 5000 years and more ago, we reproduce here a few of the photographs made at Ur by the Joint Expedition, together with a reconstruction of the Ziggurat drawn by Mr. Newton, the architect of the Expedition in 1923. For further information the reader is referred to the Reports of Major C. Leonard Woolley, Director of the Joint Expedition, printed in earlier issues of the MUSEUM JOURNAL and in the ANTIQUARIES JOURNAL.

It will be seen that many structural details are entirely wanting in the photographs and these illustrations leave us in entire ignorance as to some of the methods resorted to by the builders. Sometimes, however, these details and these methods though apparently absent and unrevealed in the remaining structures may be inferred with a high degree of probability or deduced from evidence inherent in the workmanship or arrived at by observation of the debris or restored by imagination out of suggestions offered by the general condition of things and their fitness, with the help of translated texts. Within a certain margin the results obtained are capable of demonstration even in small details; outside of that margin there may be sometimes a space where conjecture plays a part. To give an example; in the very early temple of the Goddess of Creation excavated outside the walls of Ur in a small suburb of the city called Tell-el-Obeid, a building in which the destruction was very complete, there were found in what had been the, interior of the temple certain sections of long copper casings, square in cross section. The inference was that the ceiling had been supported by wooden beams encased in copper. This is not to be regarded as mere guess work. Some of the ancient texts that have been translated and that describe architectural performances of builders mention beams or other woodwork overlaid with copper, silver or gold. Not to recognize the copper casings found in the temple just mentioned as clear evidence of the methods employed in the construction of the ceiling would amount to a lapse of intelligence. A great deal of the excavator’s work depends on observations upon conditions much more obscure and difficult than this. In this article nothing is presented in the way of restoration or reconstruction except the drawing of the restored Ziggurat prepared by the late Mr. E. F. Newton who was architect on the Joint Expedition during 1923-1924. It is rather the purpose of this article to present by means of photographs the actual situation that arises in the excavations and some of the problems that present themselves to the members of the Expedition that is engaged in digging up the City of Ur. To Dr. Legrain, no less than to Major Woolley, we are indebted for our information, though these scholars conducting the work at Ur arc not to be held responsible for such observations as are made in this article, or for inferences drawn from their scholarly labours.

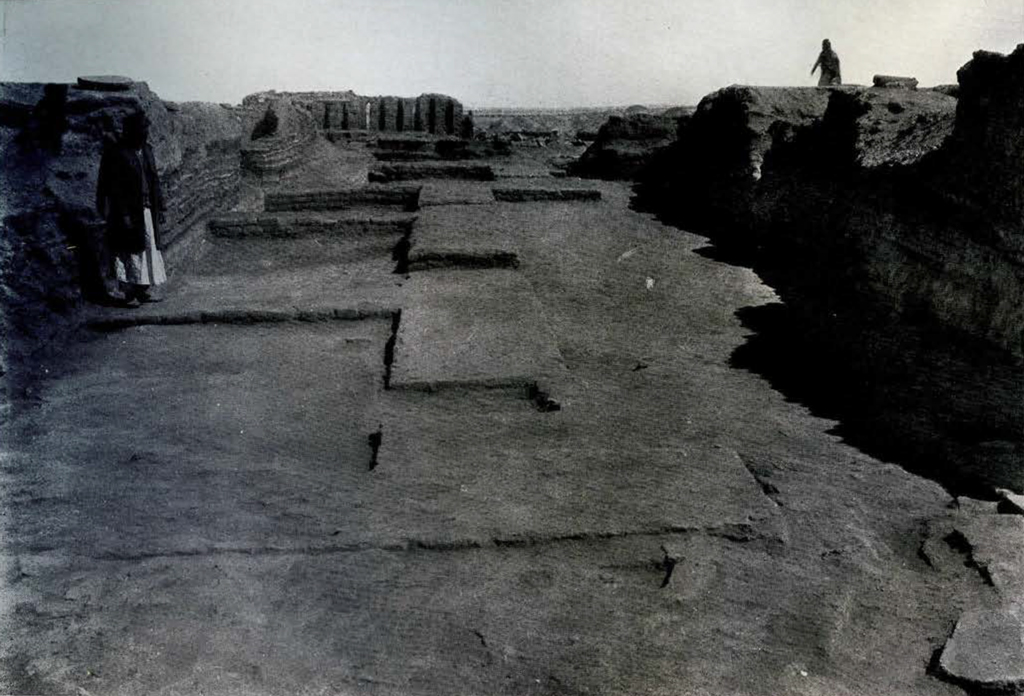

The photograph opposite shows a condition that presents itself when the rubbish is cleared away, walls and floors of different periods are exposed. Everything is of brick, the usual size being about 12″ x 12″x 3″ or 14″x 14″x 4″ or 12″x 6″ x 3″. The sizes vary considerably. Square bricks occur oftener than the oblong form.

The different structures and periods of construction shown in this photograph are as follows.

- The wall sustaining the platform on which the Ziggurat was raised; built by Ur-Engur about 2600 B.C.

- A later wall of the same enclosing the former; built by one of the Larsa Kings 2000 B.C.

- A still later wall of the same enclosing the former two and built by Kuri-galzu about 1600 B.C.

- A pavement laid down by Sinbalatsu-ikbi, about 650 B.C.

In the example opposite may be seen how the construction work of widely separated periods becomes consolidated and how involved are the problems that confront the excavators.

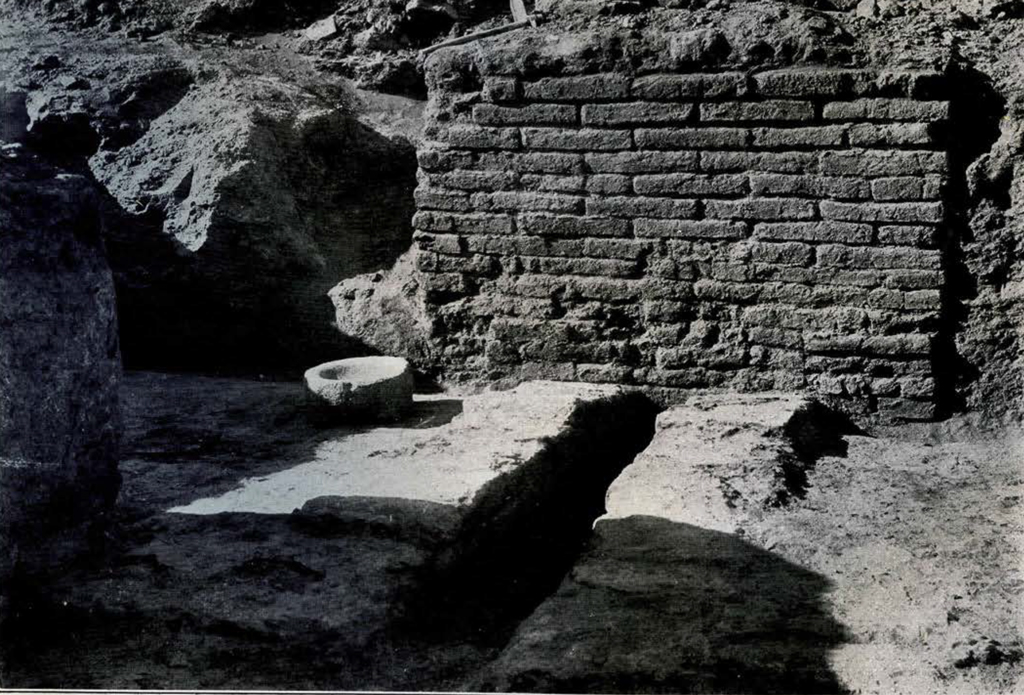

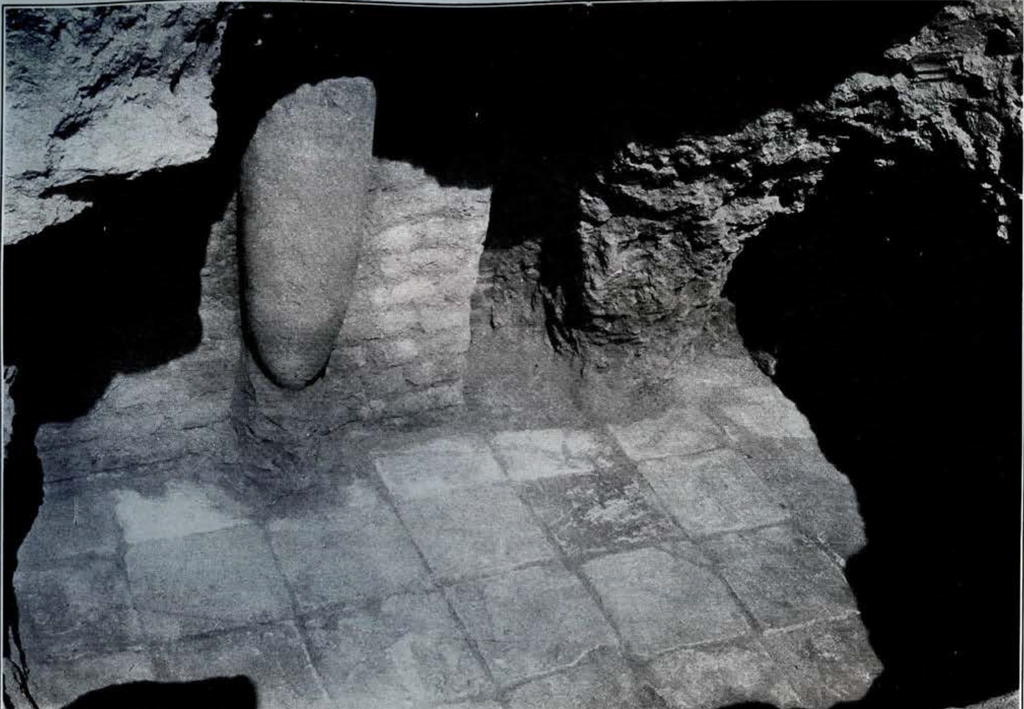

Special features that come within the view shown in this photograph are walls and floors and a structure that is common to architectural methods at Ur and other Mesopotamian cities, namely a hinge box forming the characteristic feature of a doorway. The hinge box is a strong receptacle built of bricks and enclosing a heavy block of hard stone. On the upper central surface of this stone is a large socket and on a part of the surrounding surface a panel of inscription.

The photograph shows a space within the Hall of Justice (E-dublal-mah).

- Brickwork of the Second Dynasty about 3000 B.C.

- A front wall built by Bur-Sin about 2200 B.C.

- Hinge Box of Bur-Sin 2200 B.C.

- A front wall built by Ishme-Dagan about 2000 B.C.

- A floor laid by Ishme-Dagan about 2000 B.C.

- A floor laid by Kuri-galzu 1600 B.C.

- A floor laid by Nabonidus 550 B.C.

A brick altar in the temple of Ningal, the Moon God’s wife. One part of the structure, as can be plainly seen, is older than the other. The smaller and older altar was enlarged by Kuri-galzu about 1600 B. c. The bricks of the later construction rest against and upon those of the earlier structure. It will be understood that structural work of this kind would be covered with some thin material such as gold, silver, copper, bronze, mosaic or woodwork.

A regular feature observed in many buildings and corresponding to different periods at Ur is the drainage. The drain here shown is in the temple of Ningal, the wife of the Moon God. It is lined with bricks and passes beneath the floors and beneath the walls. The period is that of Sinbalatsu-ikbi, 650 B. C. Such drains served to carry off the sewage from the interiors of the buildings. It was conducted into the desert or else emptied into vertical drains that let the drainage down to a depth in the sandy plain where Nature took care of it and where it was rapidly absorbed.

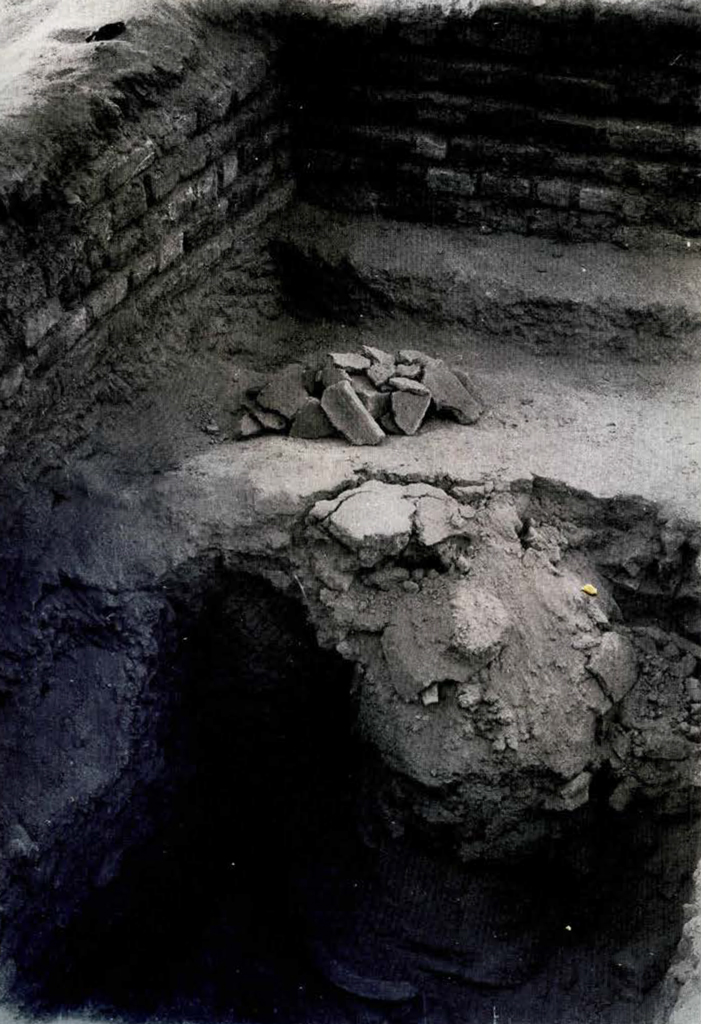

The photograph illustrates an interesting phase of the excavators’ work at Ur. The object in the foreground is a clay cone shown in situ as found beneath the floor of the temple of Ningal. Its surface is covered with writing and it was placed in its position by one of the later builders who restored the edifice, to commemorate and record his interest in the temple and his inauguration of the work of rebuilding. This represents a practice resorted to by all of the kings who indulged in building operations, to associate their names with their buildings by means of those inscribed cones hidden in the structures that they raised. The object itself, cone shaped or wedge shaped, presumably symbolizes the art of writing or the cuneiform character. Magic was probably one of the associated ideas.

A storeroom in the temple of Ningal. The circular foundation formed the bottom of a bin for the storage of grain or some other provision or supplies. Period of Kuri-galzu, about 1600 B. C.

The disklike floor is made of burnt brick firmly imbedded in bitumen. The sides of the cylindrical bin were constructed of the same materials. In the case illustrated the sides had disappeared, the bricks being used perhaps by some later builder. In other storerooms parts of the walls of the bins remained in position, giving the clue to their construction and function.

A narrow street paved with bricks. It is very much like the narrow, irregular streets in any Oriental city of the present day, such as Bagdad or Damascus or Cairo, except that it is infinitely better paved. The brick foundations on either side of this street show the general condition of the buildings at Ur after excavation. Sometimes even less of the walls remain, and often nothing but traces of the foundations. The large building in the distant part of the picture is rather unusual in the amount of construction that remains standing.

A street leading to the temple of Ningal, wife of the Moon God, was labeled by the excavators Ningal Street. In this view of Ningal Street is seen what is left of the Bazaars that lined one side of it. The time is that of Kurzi-galzu about 1600 B. C.

This and the other pictures show the appearance of things immediately after excavation, when brick pavements have been swept clean. Before excavation nothing was visible but sand. It will not be long before these cleared spaces will again be covered by the drifting sand.

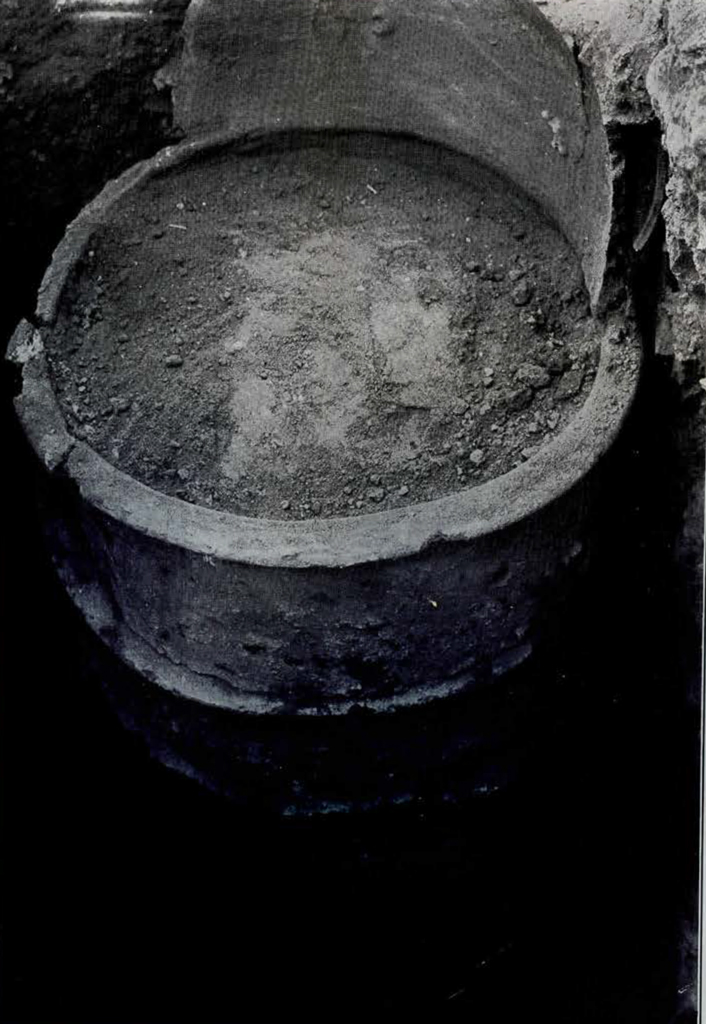

The collapsed sections of a vertical drain found beneath the floor of a room in the temple of the Moon God. Date about 2000 B. C. The sections of pipe are made of clay burnt hard. Better preserved examples will be seen in other photographs, and different systems for joining the sections have been observed. These vertical drains served to carry off the surface water from the pavements and gutters or else to receive the interior drainage of the houses and temples and conduct it to a depth sufficient to dispose of it effectively.

A room in the Hall of Justice. Under the brick floor where it has been removed are seen the upper sections of vertical drain pipes of burnt pottery. In one of the bricks is seen the opening to another drain. In these examples the sewage from an interior went directly into the vertical drains from sinks or catch basins. The function of the room may have been that of a wash room or lavatory.

In the south wing of the Hall of Justice this large pottery drain came to light beneath the pavement. It is made of cylindrical sections of uniform diameter and composed of burnt clay, placed in a vertical position one upon another. This example illustrates a familiar type of drain, in which the sections are simply brought into contact with each other. How the joints were sealed is not altogether clear but it is probable that bitumen would be used in the interiors of the drains for that purpose. This substance was very familiar to the builders and much used by them in the construction of walls and pavements. They would naturally recognize its suitability as a lining for drains.

A floor laid by Sinbalatsu-ikbi about 650 B. C. It is made of unstamped bricks, flat on one side and convex on the other. This type of brick was peculiar to certain periods as has been proved in numerous ways. It thus becomes one of the means of determining the age of a structure in which it occurs.

This photograph illustrates also how completely the desert has encroached on the City and how it lies in wait at its gates to swallow it up again almost as soon as the excavators shall have left.

A pavement laid down by Sinbalatsu-ikbi about 650 B. c. of plano-convex brick. The end of a pottery drain appears at the break in the pavement. This form of drain seems to have been improvised from a certain form of tall pottery jars. By having the bottoms knocked out and being brought together so that the narrow neck of one fitted into the bottom of the one next below, a series of these jars were made to form a very practical drain.

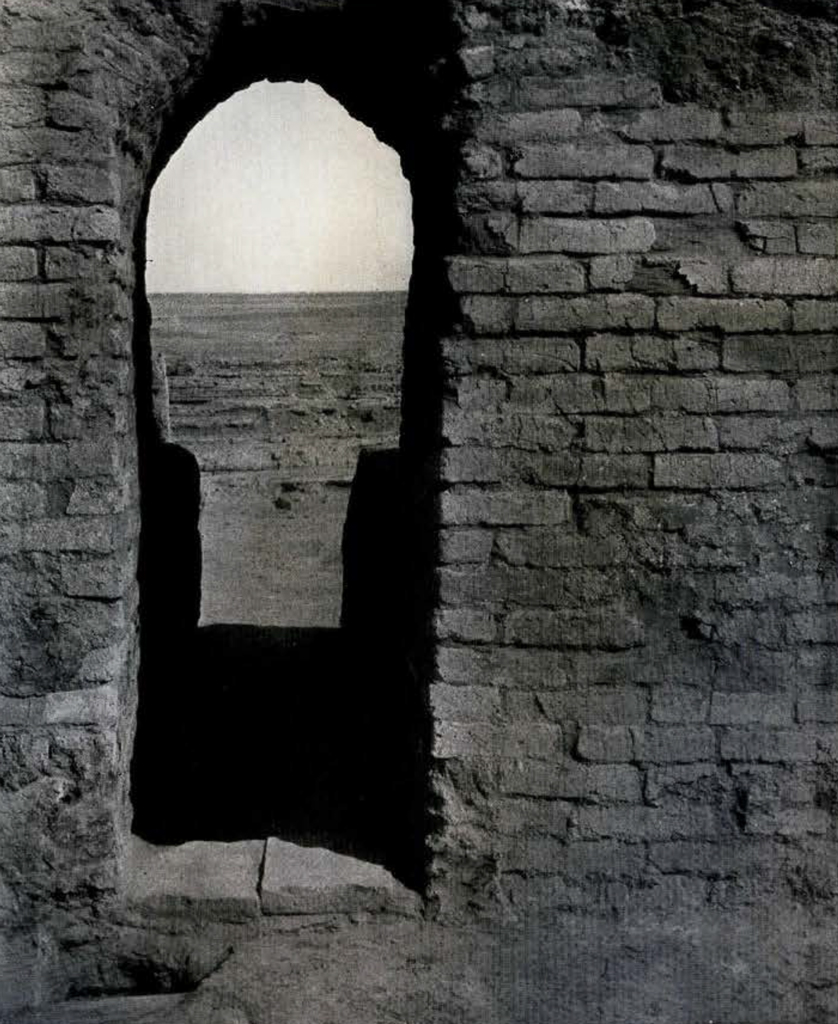

The brick wall of the Sanctuary in the Hall of Justice was found to be pierced by a doorway with a round arch. The structure belongs to the period of Kuri-galzu about 1600 B. C. The round arch would therefore appear to have been known as early in history as that date would indicate. How frequent was its use cannot be decided because so few buildings have so much of their doorways left for observation.

A storeroom in the temple of Ningal showing an earthenware jar in position as found in the excavations. Period of King Kuri-galzu, about 1600 B. c. Such a storeroom would probably be for oil or wine, kept in jars. A storeroom of a different type for keeping dry stores has been shown already. Each temple, palace or dwelling had its own storeroom and large deposits were kept in connection with the government offices.

A kitchen with floor of bricks and some of the stone utensils in the house of the high priestess. The stones are for grinding and are of a hard variety. All stone had to be imported from some neighbouring country such as Persia because the plain affords nothing of the kind.

The Hall of Justice is now roofless and its walls are reduced in height by the action of the elements. Different periods of building, rebuilding or restoration can be traced throughout its structure. The arched doorway belongs to the period of Kuri-galzu about 1600 B. C. The recessed appearance of the walls, giving the effect of a series of stout piers or buttresses of brick is a familiar feature of construction at Ur though by no means a general one.

The platform wall of the Ziggurat. The inner of the two visible walls, still intact, was built by the Kings of Larsa about 2000 B. C. The outer broken wall that rests upon the inner was the work of Kuri-galzu about 1600 B. C. The forms and stamps upon the bricks serve to identify the period and the names of the builders, who in succession, enlarged, strengthened, or restored the platform wall.

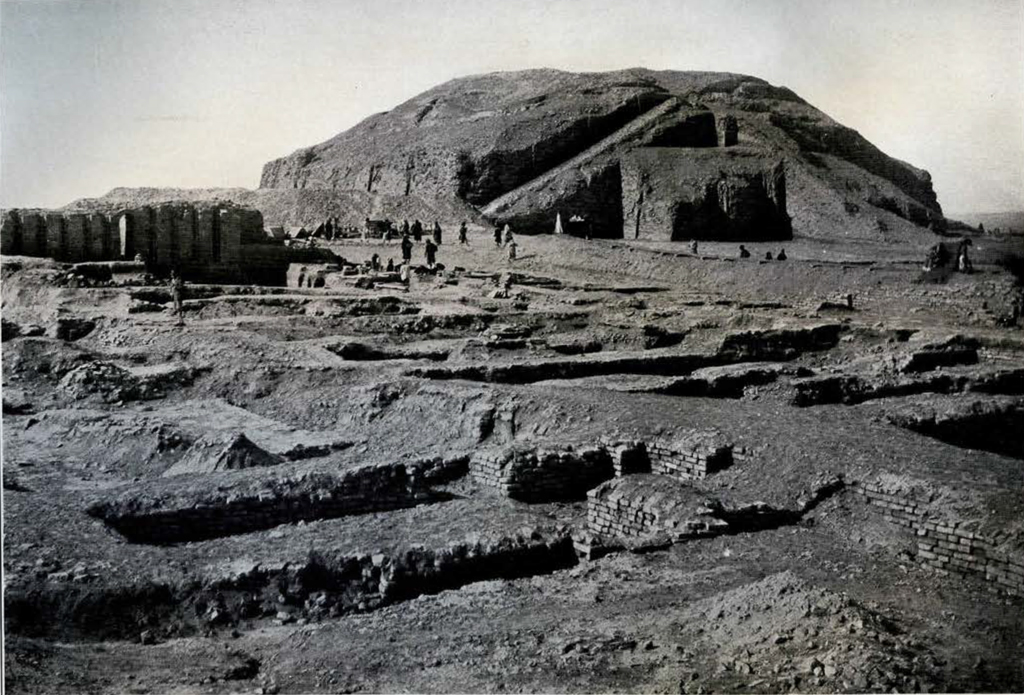

In the background is seen the Ziggurat and at the left a corner of the Hall of Justice. Many different periods of construction are represented in this picture. The Ziggurat is about 2600 B. C. The walls in the foreground about 2000 B. C., the Hall of Justice at the left—l600 B. C. and the pavement in the immediate foreground 650 B. C. The Arabs standing about are the workmen employed in the excavations. They are recruited from the Bedouin tribes of the neighbouring desert.

A general view of the excavations at Ur. All the ground seen in the picture has been cleared. Before excavation nothing was seen but sandcovered mounds. The picture is made from the Temple of the Moon God looking toward the Ziggurat.

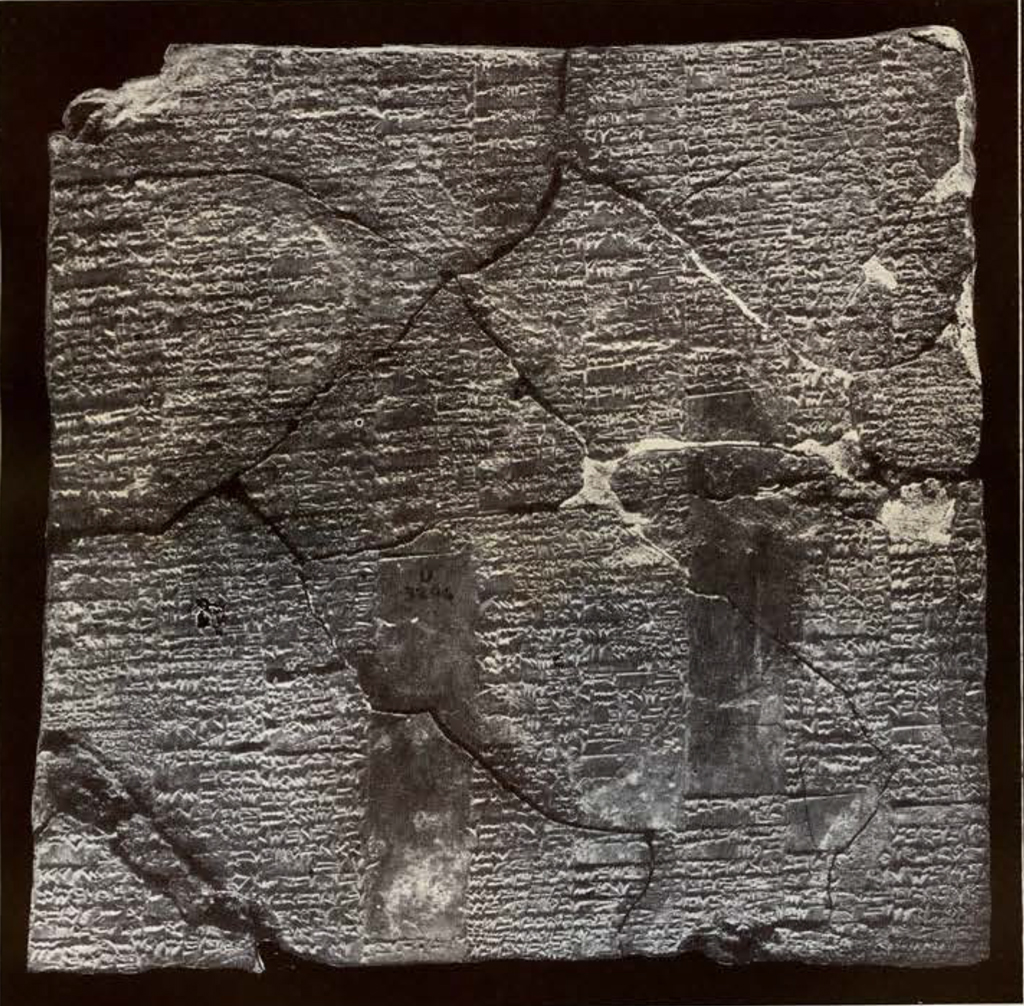

In the fort of Warad-Sin were found for the first time inscribed cones remaining in position. The class of object had already been known in many examples but the manner in which they had been used had not been known till these cones of Warad-Sin were found in situ in the core of the walls of the fort that he built. This purpose would appear to have been partly magical since they may be supposed to represent or symbolize the art of writing by means of the cone shaped or wedge shaped signs on clay. They were also commemorative because the writings on the surface of the cones relate to the reigning king and his works, especially his interest in the building with which the cones are associated.

To the northwest of the Ziggurat the excavations revealed a fortress built by King Warad-Sin about 2060 B. C. Embedded in the walls of this fort were found a number of the usual clay cones that still remained in their positions and contained the inscriptions of Warad-Sin, enabling the excavators to identify the name of the builder of the fort and to fix its date. Three of these cones are seen in the lower part of the picture.

Three of the inscribed clay cones of Warad-Sin found in the core of the walls of the fort that he built at Ur; 2060 B. c. Many of these cones have been found, varying in size from five to ten inches in length. They were commonly used by rulers or their builders to place in the walls or foundations of their buildings to associate their names with their work presumably for the information of posterity and perhaps in conformity with some custom originally embodying ideas of magic.

The south wing of the Hall of Justice looking across the courtyard. In the picture are seen labels attached by the excavators to different features after identification, these marked features represent different periods of building, determined by one or more of the methods that have been indicated in the preceding pages. The picture shows very well the varying stages of decay that at present enwraps the city. The building in the distance is one of the best preserved at Ur. From that condition there is a gradation of decay till the very traces of the foundations are effaced.

The East Wing of the Hall of Justice after excavation. The cross marks the position of the room in which many inscribed tablets were found. A few of these tablets will be shown in the sequel. They relate to various matters and are in varying states of preservation. Many of them are unburnt and when found are sometimes hard to distinguish from the substance in which they are embedded. The room was presumably a part of the archives of the city.

One of the winding passages in the Hall of Justice. This building which was one of the best preserved structures yet excavated at Ur was also one of the most elaborate and complex. It had many rooms, halls and passages connecting with each other. All of the walls were thick and substantial but none of the rooms would be considered large today. This may have been due to their size being limited by the technical difficulties of constructing roofs and ceilings over wide spaces. The circular arch was sometimes used in doorways but whether or not the circular vault was ever employed we do not know.

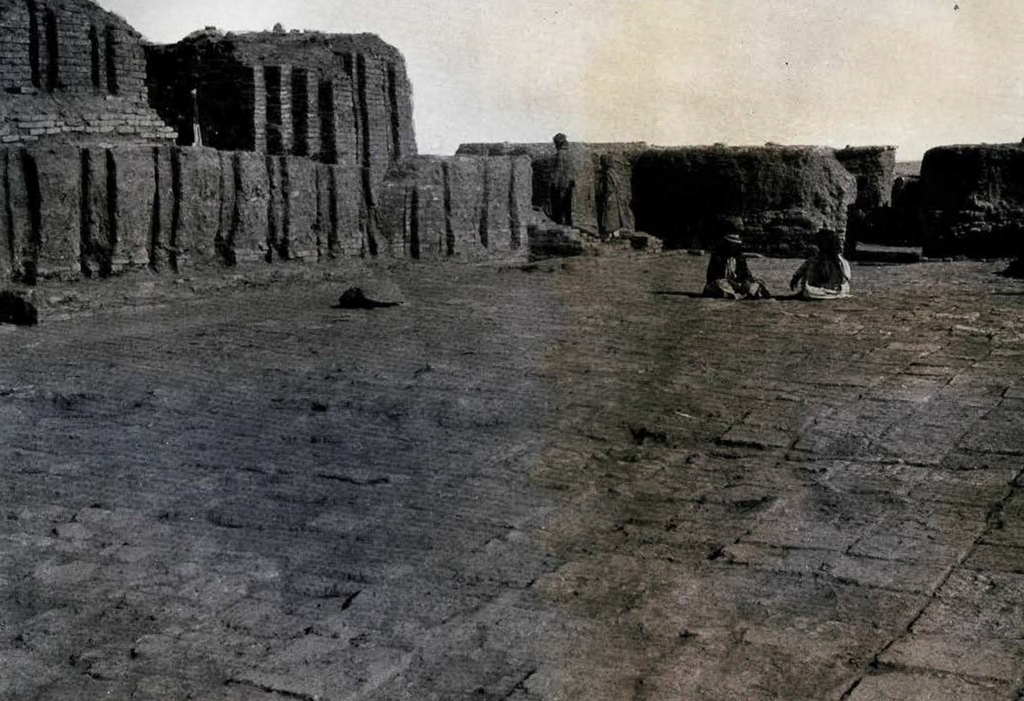

A courtyard in the Hall of Justice and the processional way leading from it, after excavation. The name of this complex building, covering a large area and enclosing many passages, rooms, closed halls and open courts, was E-dublal-mah meaning the Place of the Law or Justice. It was the Department of Justice in the Government of Ur. It was where the Judges sat and read the law and made decisions and pronounced sentence. It also served many other uses connected with the Administration of Justice.

The Hall of Justice at Ur after excavation. Date 1600 B. C. The terraced construction or storeys by receding stages is a familiar feature of all ancient cities of Mesopotamia. Its most familiar aspect appears in the Ziggurat. It, or something like it, was known also in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and in this example it is seen in the design of a large building for official uses. The design was a matter of long experience from which much had been learned. One of the lessons that would be learned would be that a building in receding stages attained great solidity and strength and could be raised to a greater height than one with walls in the same vertical plane.

A courtyard in the Hall of Justice. The spaciousness of precincts of this important and complex building is well illustrated in this picture. Though many of the enclosed rooms were small, the spreading ranges and the broad open courtyards, beautifully paved with brick, gave an effect of space and must have achieved no small degree of grandeur.

A gatehouse or guardroom in the Ningal Street entrance to the Hall of Justice after excavation. A close inspection of the brickwork in many buildings of different periods reveals the fact that the bricklayers in general were careful to break joints exactly and methodically in every course, but sometimes it will be found that the workmen were not so particular and laid two or more courses with the joints together. Floors and pavements were always laid with the joints between the bricks forming continuous lines in both directions.

The southern part of the Hall of Justice after excavation. The members of the Joint Expedition have labeled the different features for their own guidance, as each was brought to light and identified by them according to the methods already described.

The members of the Joint Expedition of the University Museum and the British Museum at Ur, beside the Hall of Justice, season 1924-25. The amount of sand and debris that has to be removed in the clearance of such a building may be realized from the fact that none of these walls were visible when the excavation began.

A room in the Hall of Justice called the Sanctuary. At the entrance are two brick steps with rounded ends. Floors in this complex building were on different levels requiring sometimes the introduction of steps at the entrances. In this instance the two steps are rounded at the ends, are of different lengths and both exceed in length the width of the doorway.

This piece of brick wall in the Hall of Justice shows plainly the King’s stamp on some of the bricks. The stamp is that of Bur-Sin who reigned about 2200 B. C. Sometimes the stamp was placed on one side of the brick and sometimes on an edge. In the latter case the stamp might show if the stamped edge happened to be in the face of the wall. In the former case the stamp would never show. Indeed it would appear that the stamps were not intended to show in the construction, for it is probable that such brickwork was covered with plaster.

Image Number: 8762b

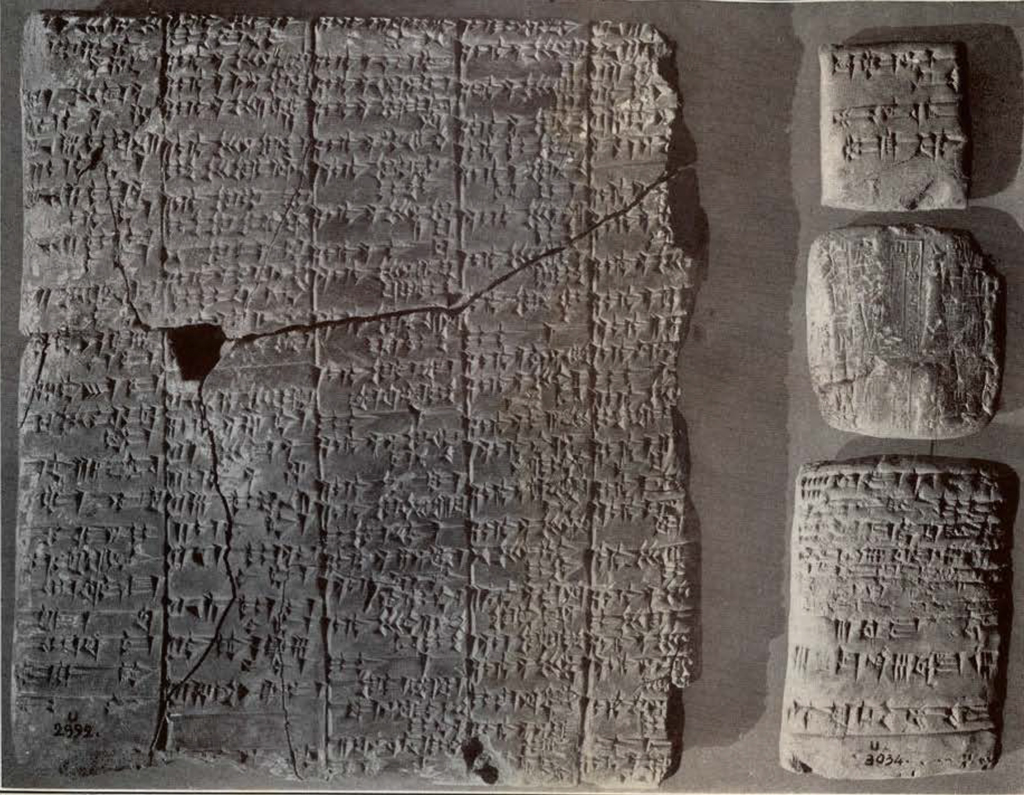

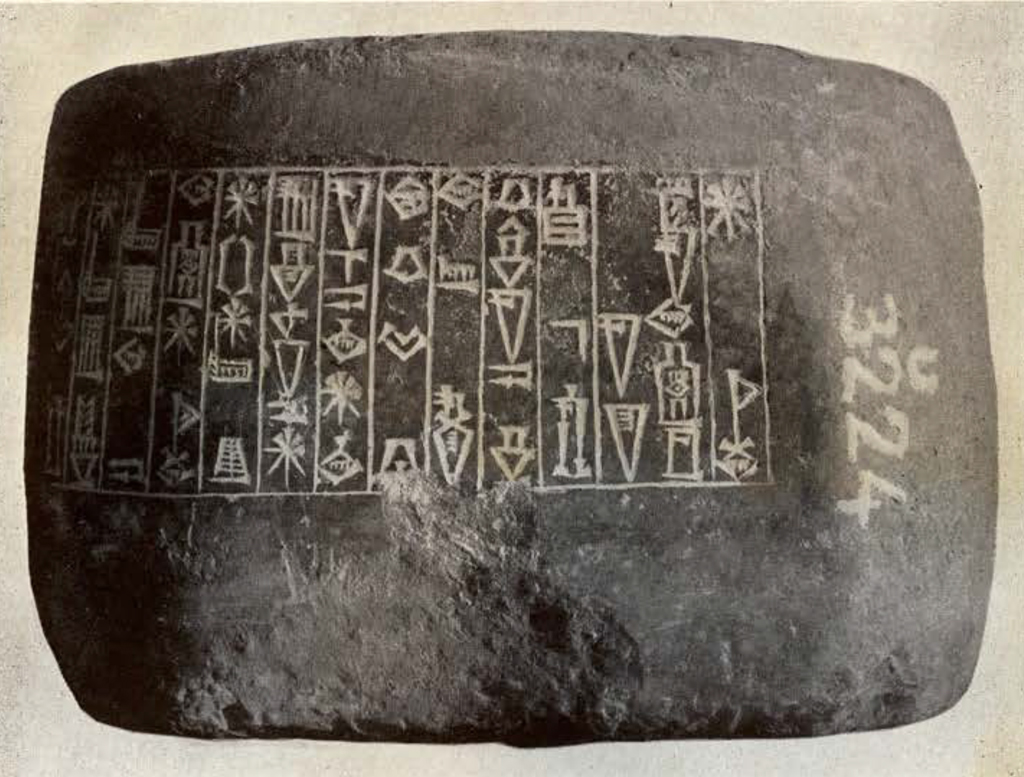

A large clay tablet with many lines of writing found in a room of the Hall of Justice. The contents of the tablet consist of a record, for a definite period of time, of the receipts of wool in the government offices that stood within the temple enclosure and were a part of the Moon God’s establishment. Many tablets referring to the work of administration were found in the same chamber which would appear to have been a record office or filing room connected with the offices of administration of the Moon God’s government. A similar tablet found in the same place gives the roll of 98 women and 63 children employed in a factory run by the Temple or a subcontractor. It gives the weight of wool issued to each woman and the quantity of cloth turned out by each, recorded by weight, measurement and quality, with an allowance for wastage of wool in the weaving. Other tablets specify the rations issued to each woman and child, the allowance varying with the age of the worker—an old woman receiving the same as a child. Deaths are recorded together with stoppage of rations and every detail is minutely tabulated.

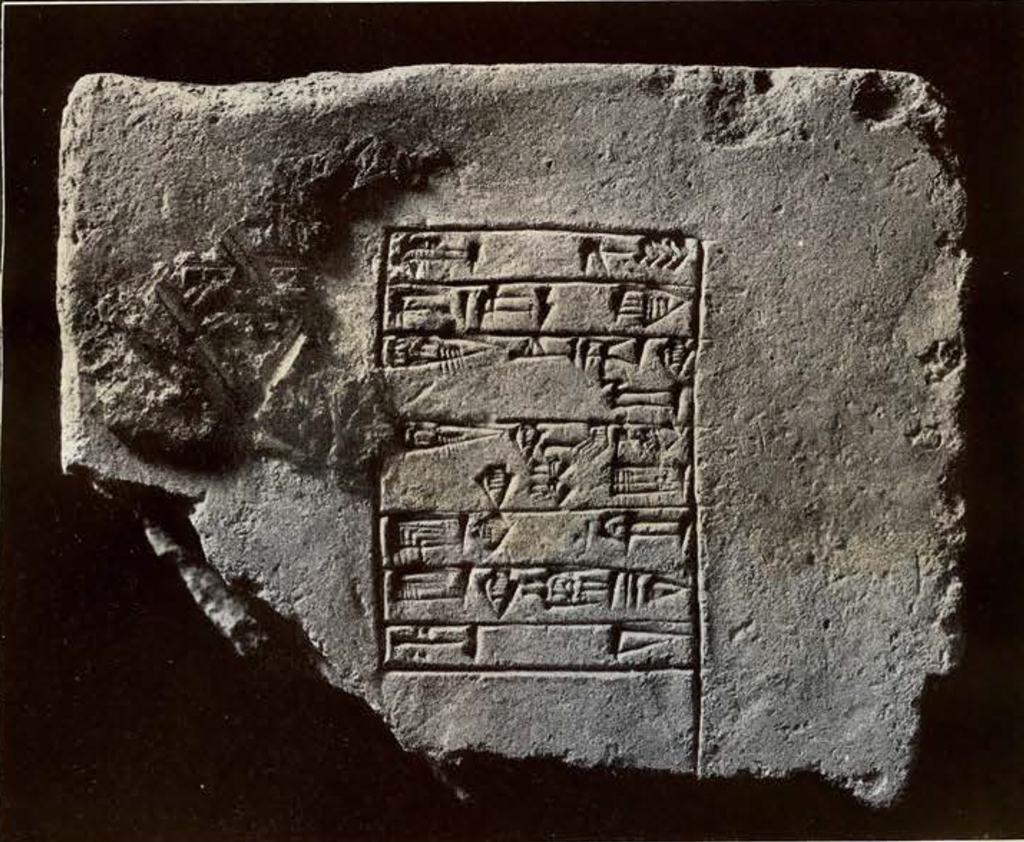

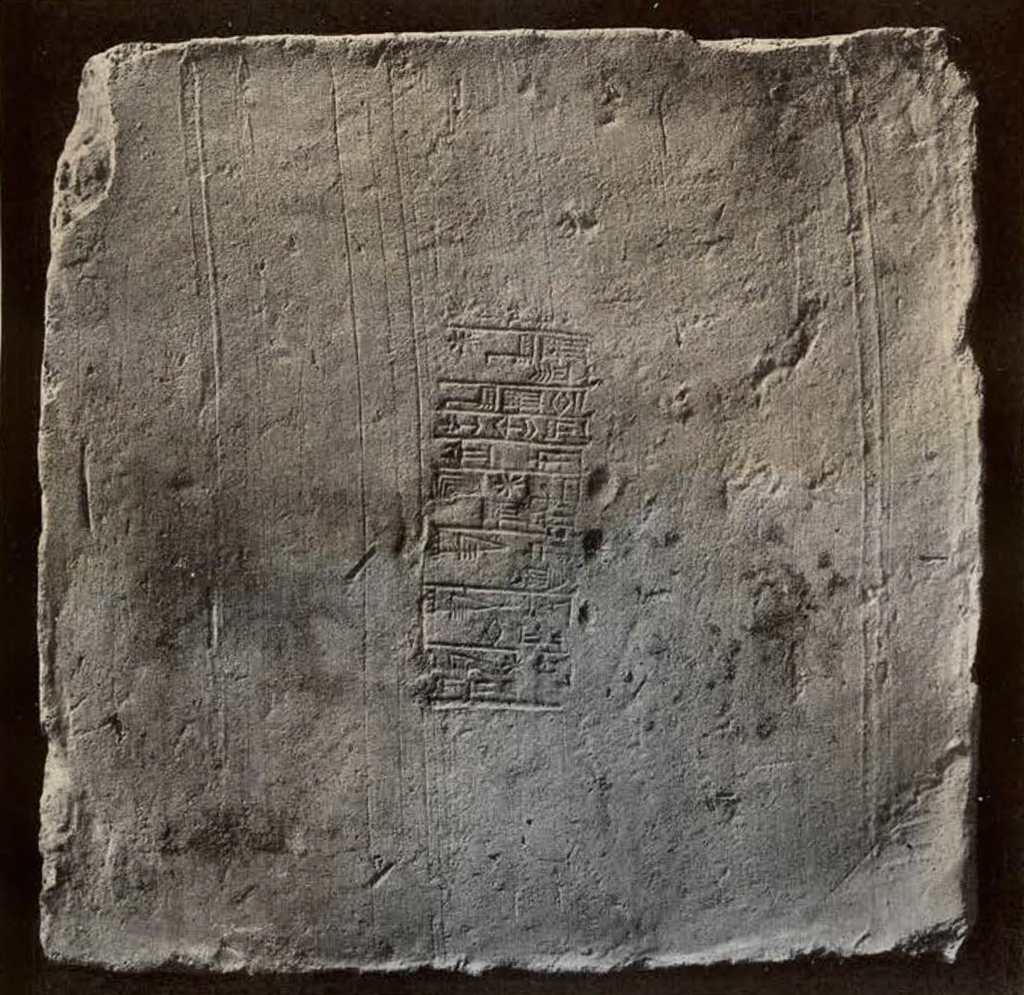

A group of inscribed clay tablets found in a room in the Hall of Justice. All of these tablets after being recovered are baked in an improvised furnace at the house of the Joint Expedition, to prevent them from disintegration. They can then be cleaned without injury. The tablets shown have been subjected to both these processes.

The larger tablet gives details of information about the management of the factory connected with the Government of Ur. It was within the sacred enclosure of the Temple and came within the Administration of the City and the Temple. A number of tablets have been found relating to this cloth factory. It employed 98 women and 63 children at its looms and the tablet here shown is the record for one month of the rations issued to these women and children, for all of which they where charged, each having a separate account.

The next largest tablet on the illustration opposite is a receipt for gold and silver paid into the government Treasury. The next is a receipt for the sheepskins also paid into the Treasury and the smallest is likewise a receipt.

It is clear from such records that the building trade at Ur was developed along many lines corresponding to many uses. There were temples, palaces, office buildings, treasuries, libraries, dwellings and many other classes of buildings.

The members of the Joint Expedition of the University Museum and the British Museum at Ur, beside the Hall of Justice, season 1924-25. The amount of sand and debris that has to be removed in the clearance of such a building may be realized from the fact that none of these walls were visible when the excavation began.

Image Number: 8763a

Image Numbers: 8452, 8453

Image Number: 190400

Image Number: 9108

Image Number: 190435

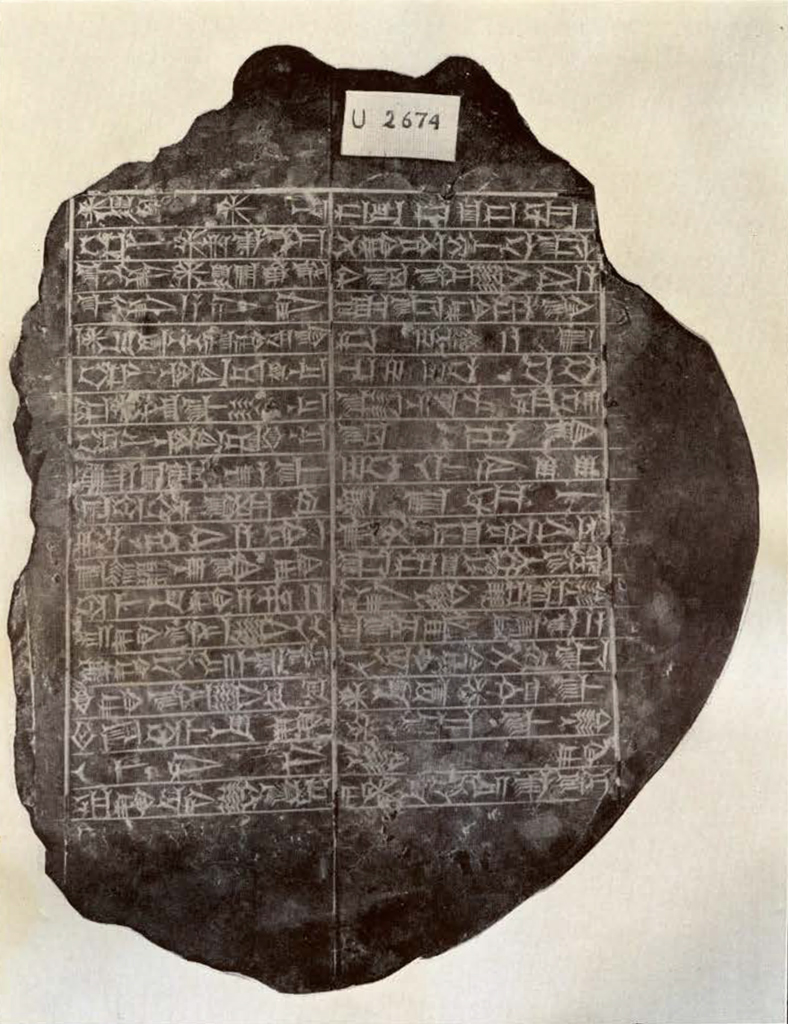

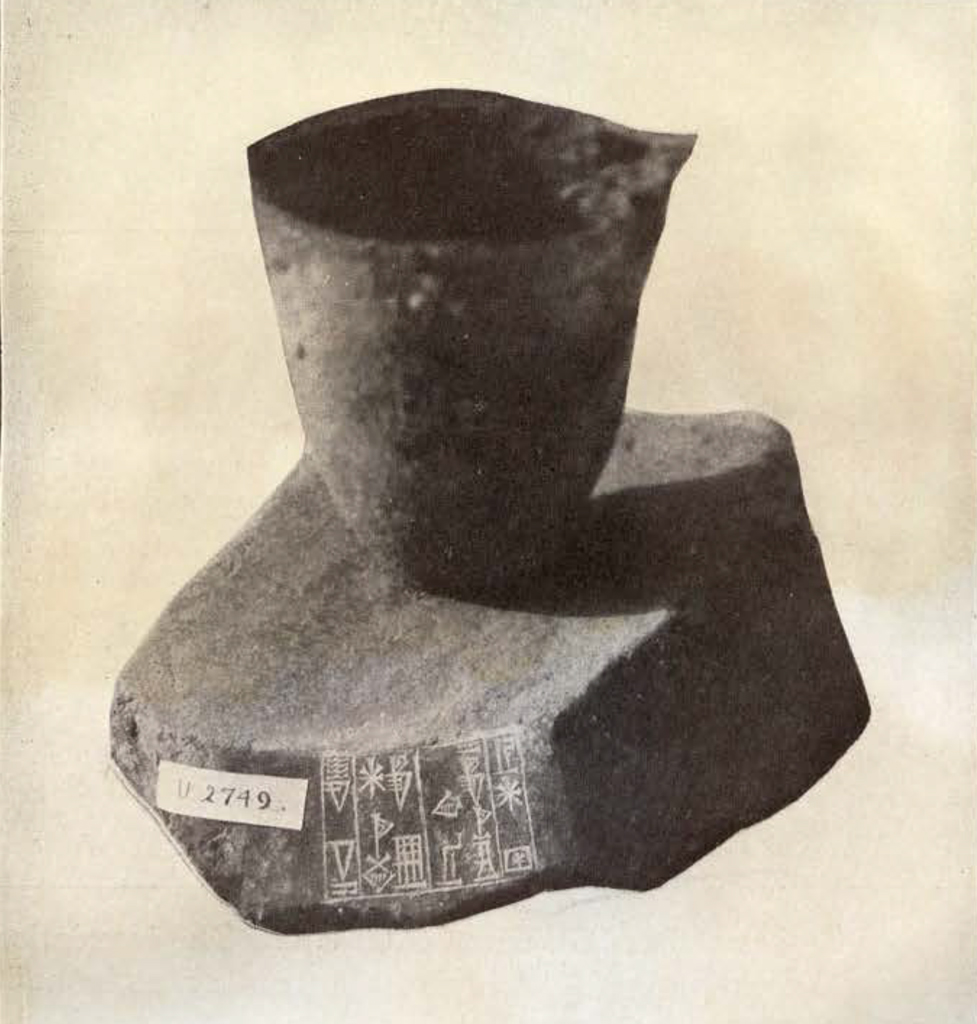

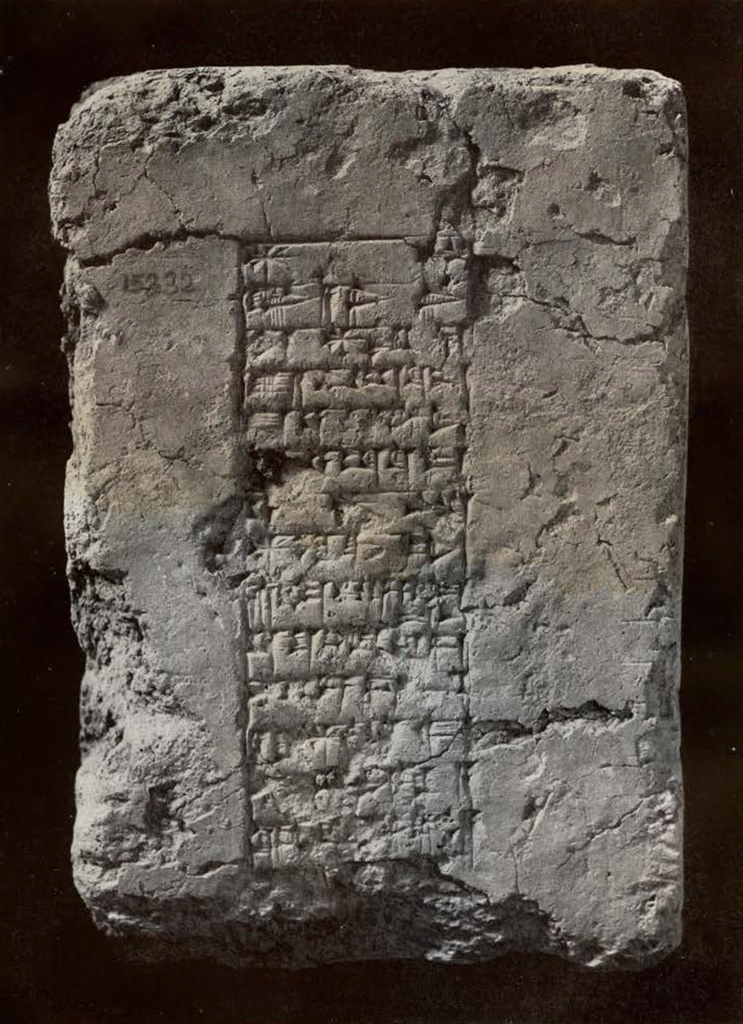

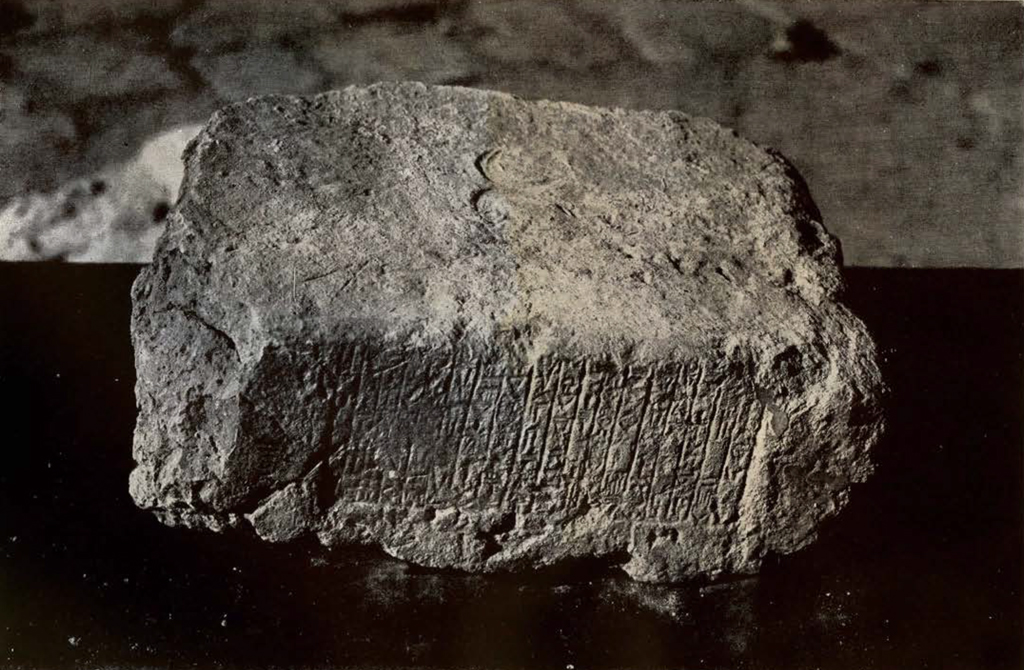

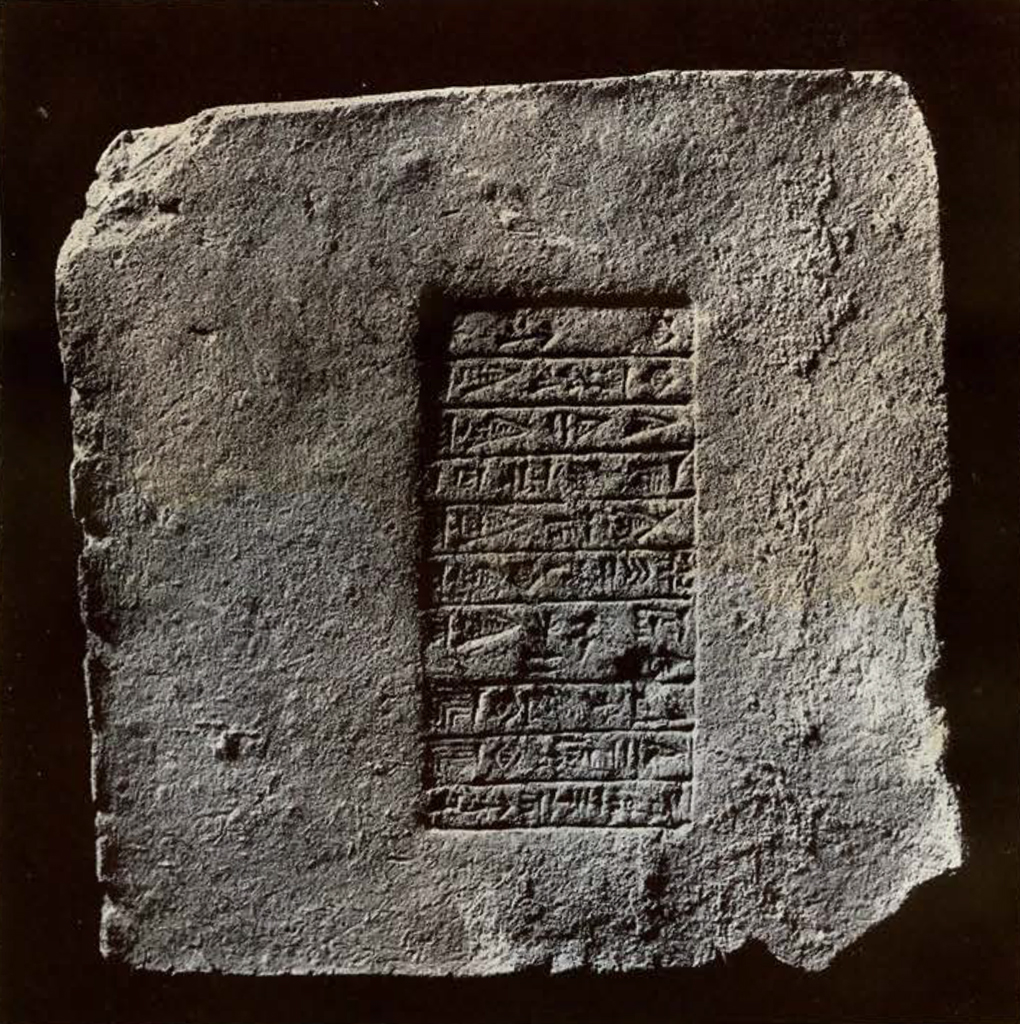

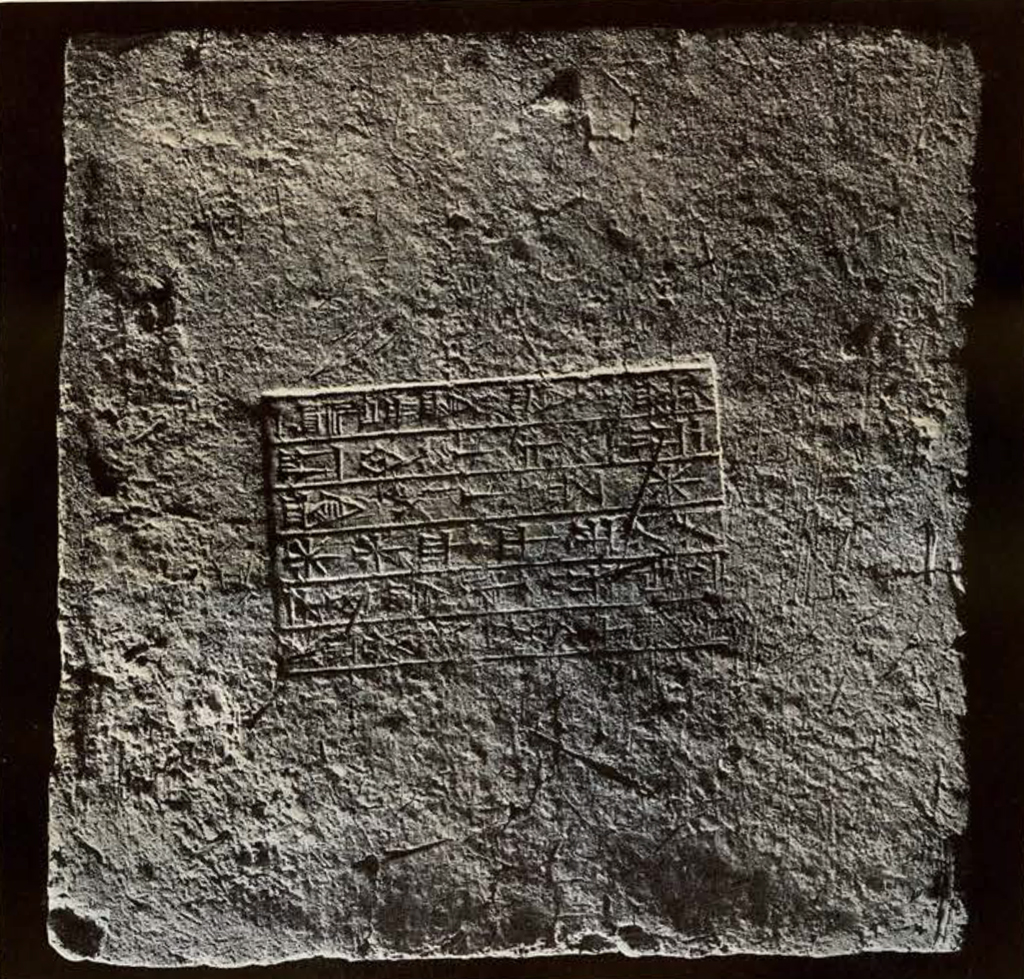

The position and function of the door socket in the architectural and ceremonial life of Ur is explained on page 222. The door sockets are usually made of diorite, a very hard, fine grained black stone. The inscription in each case gives the name of the king in whose reign the building was erected, together with mention of the principal events with which his reign is connected. Sometimes also there are lines of magic, a curse or an incantation. A door socket of Ur-Engur, for instance, found in the Hall of Justice or Place of Judgment, recording the name and works of King Ur-Engur, lays a curse in the name of the Moon God and his wife on anyone who shall remove the stone. It reminds one of Shakespeare’s lines on his tomb. Some of the door sockets are shown on the following pages.

Door Socket of Kuri-galzu, 1600 B. C., in situ. The block of diorite with its inscription is encased in a box built of brick. The socket measures about 5 inches in diameter, indicating a thick and heavy door.

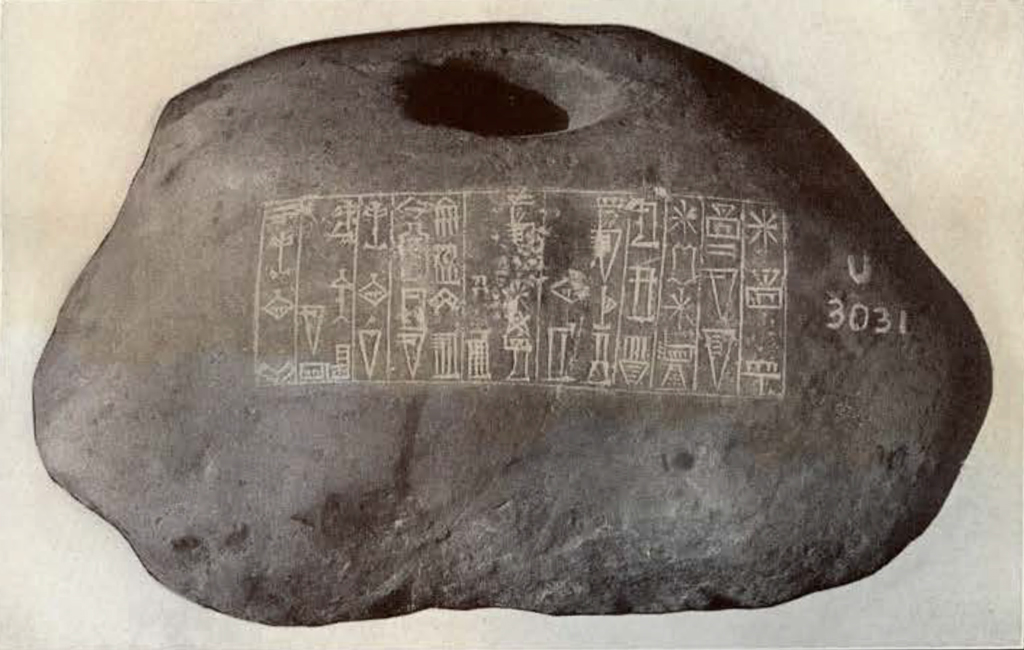

One of the most reliable ways that the excavator has at his command for identifying any building, pavement or wall is by means of the stamps on the bricks. On the following pages are shown some of these stamped bricks. Bricks varied somewhat in size and shape even during the same reign. Sometimes they were oblong but usually they were square. Sometimes they were burnt and sometimes only sun dried.

The brick shown opposite bears the stamp of Shulgi, King of Ur, 2260 B. c. At the left side is seen a mass of adhering bitumen. Bitumen, found in lakes in the desert that are still a feature of the country, was used in ancient times for mortar in brick construction. “They had brick for stone, and slime [i. e., bitumen] had they for morter.” —GENESIS 1 1 : 3.

Museum Object Number: B15331

Image Numbers: 8070, 190725

Image Number: 8077

Image Number: 9110

Museum Object Number: B15330

Image Number: 8076, 190726

Museum Object Number: B15348

Image Number: 8079