During the campaign of 1925-26 the Museum’s Expedition at Beisan, ancient Beth-Shan in Palestine, discovered altogether four Canaanite temples, two being made during the time of Rameses II, King of Egypt 1292-1225 B. C., one under the reign of his predecessor, Seti I, 1313-1292 B. c., and one during the Tell el Amarna period, 1375-1350 B. C. The evidence shows that the southern temple of Rameses II was dedicated to the warrior god Resheph, and the northern one to the warrior goddess Antit-Ashtoreth, whose monument was discovered in the building. From the time of the erection of these buildings, as the evidence proves, up to the time when King David drove out the Philistines, about 1000 B. c., worship was carried on in both the temples, first of all by the Egyptians and their mercenaries, and later by the Philistines. These peoples seem to have taken possession of Beth-Shan at the death of Rameses III in 1167 B. C. But already before their time, as the evidence indicates, there were Egyptian mercenary troops at Beth-Shan, who, like the Philistines, came from the Aegean-Anatolian regions. At the death of the Egyptian king these troops probably took possession of the place for themselves and mixed with the incoming Philistines, whom the Egyptians knew as the Pulesti. The newcomers are never themselves described as mercenaries of Egypt but always as enemies. Burials of Egyptian mercenaries were discovered at Beth-Shan in 1922; they comprised peculiar anthropoid pottery sarcophagi of the same date (XXth Dynasty) and type as the foreign looking pottery sarcophagi found in Egypt at el-Yahudîyeh and Tell-Nebesheh. A spearhead found with a sarcophagus at the latter place is identical with that found in one of the parallel burials at Beth-Shan.

We see then that at the death of Saul in 1020 B. C. the Philistines were in actual possession of the fortress city of Beth-Shan and they were worshipping in the two temples erected by the Egyptians under Rameses II, the adoration of their Baal (whom they called Dagon) and their Baalath (Ashtoreth) doubtless being carried out in the respective temples in which the Baal and Baalath of the Egyptians were revered. The biblical references are given in I Chronicles x, 10, and I Samuel xxxi, 10. The former passage relates that when Saul died the Philistines “put his armour in the house of their gods, and fastened his head in the temple of Dagon,” and the parallel passage in Samuel informs us that “they put his armour in the house of Ashtaroth and they fastened his body to the wall of Beth-Shan.” The combined evidence, both literary and archaeological, certainly shows that, in the Old Testament, the building called “temple of Dagon” was the southern temple of Rameses II; and that the building called “house of Ashtaroth” in the one place and “house of their gods” in the other was the old northern temple of the king. In the latter connection there is really no inconsistency in the fact that the same temple is termed “house of Ashtaroth (in Revised Version, ‘house of the Ashtaroth’)” and “house of their gods,” for it must be remembered that Ashtaroth is merely the plural form of Ashtoreth. But in any case the passage in Chronicles indicates that there were two temples at Beth-Shan during the Philistine regime. The excavations have certainly proved that such was the fact.

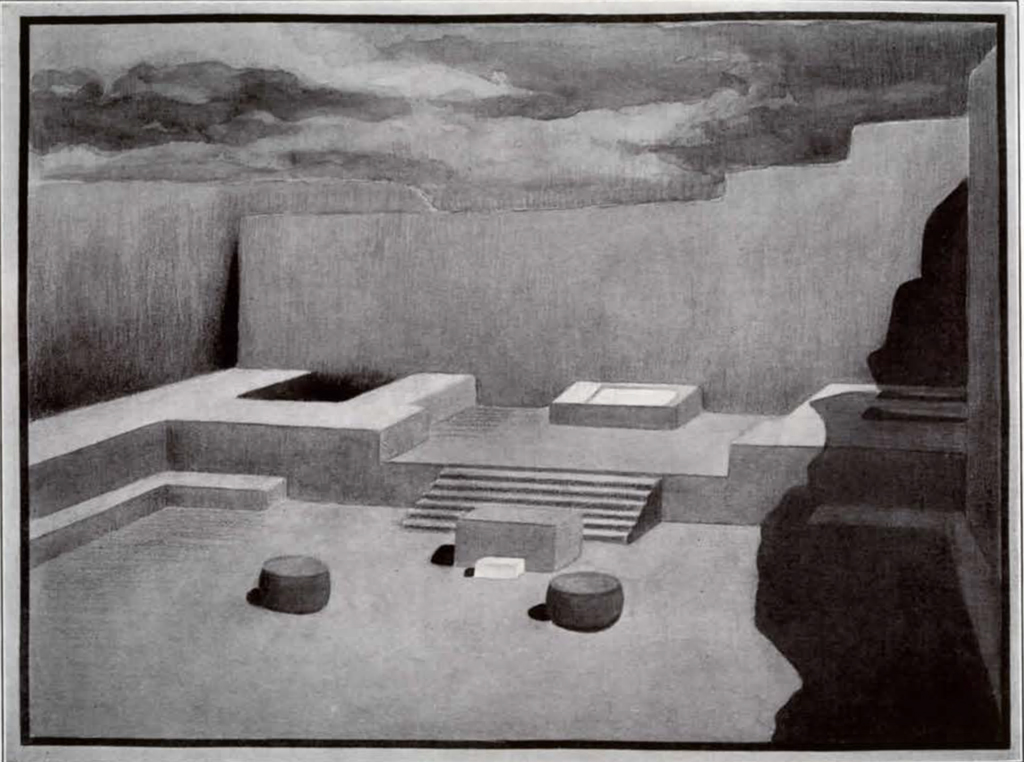

Somewhere about 1000 B. C. King David seems to have driven out the Philistines from Beth-Shan. He was probably also responsible for the partial demolition of the “house of Ashtaroth” and the “temple of Dagon.” A new floor which we found laid in the former building over the debris of destruction, and at such a height as to cover the stone bases of the four columns which they once supported, was perhaps his work. David must surely have established a sanctuary or a tabernacle to the God of Israel at Beth-Shan. If there was such a sanctuary, the only place large enough for it on the Tell (the Acropolis) was in the ruins of the Dagon temple or in the reconstructed Ashtoreth temple.

Museum Object Number: 29-103-818

Image Number: 30224, 30225

Museum Object Number: 29-103-830

Image Number: 30222b, 30223

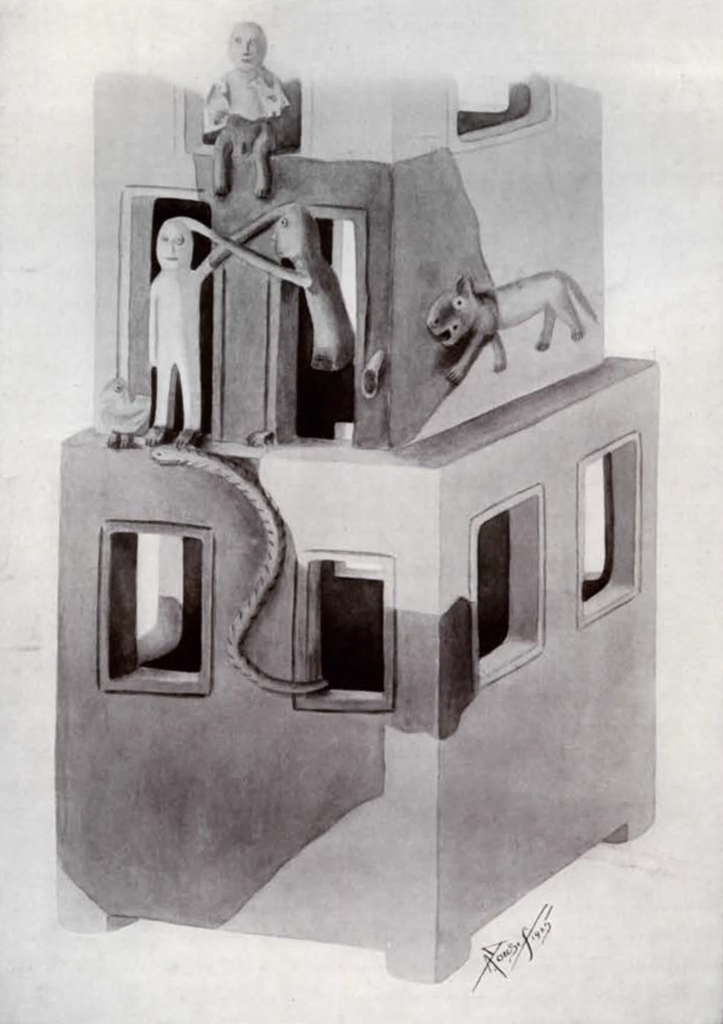

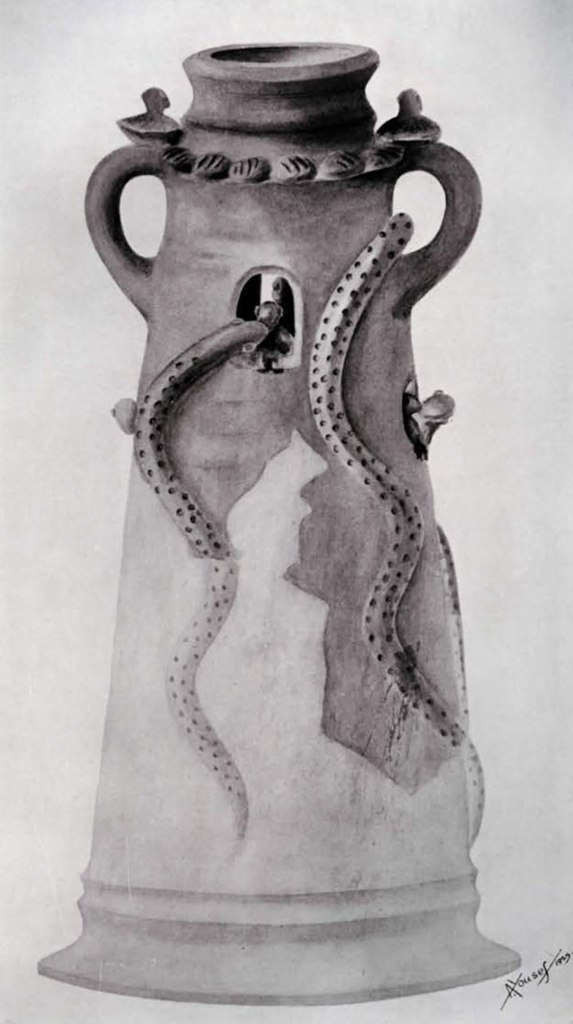

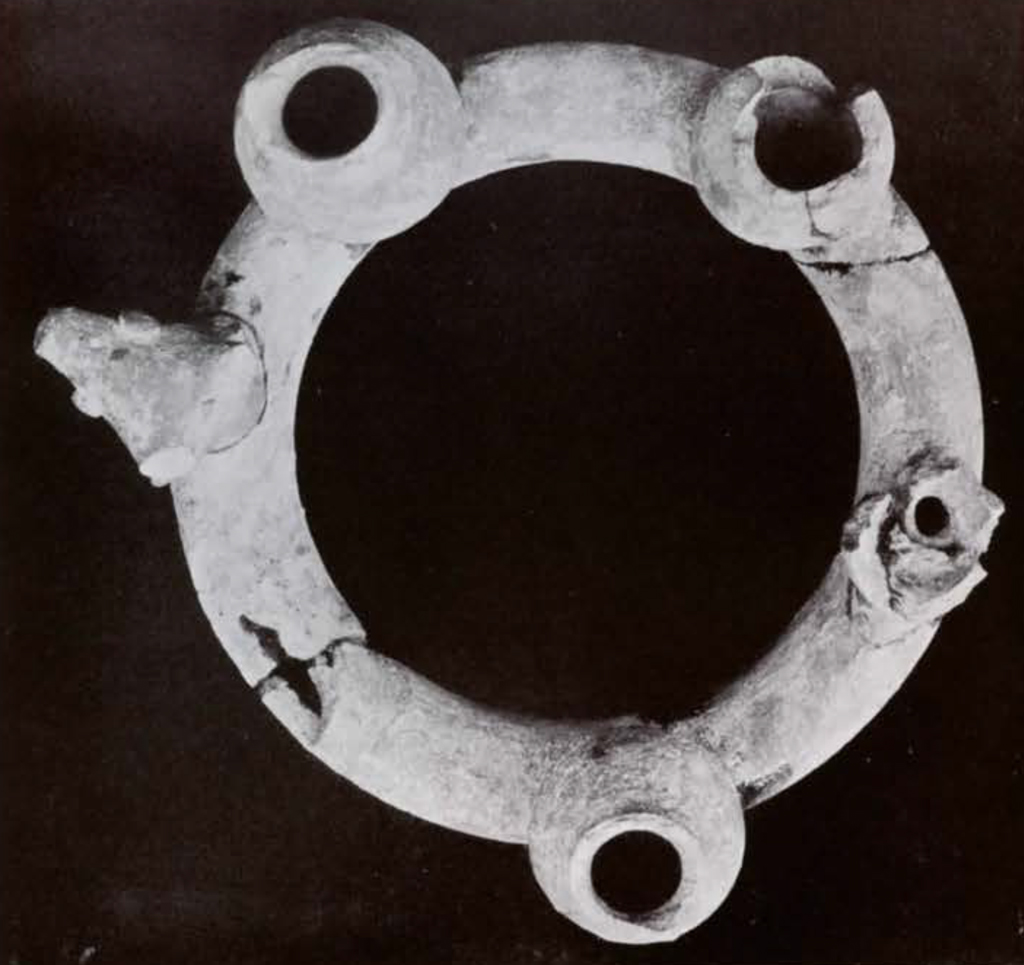

The actual walls of the temples of Seti I and Rameses II seem to have been built by the mercenaries themselves, the engraving of door jambs and stelae being the main work carried out by the Egyptian craftsmen. Some of the bricks in the temples of the latter king have signs on them which are identical in shape with certain Cretan (Minoan) signs, which fact would indicate the home at least of some of the mercenaries. Other Cretan influence is present in the shape of the cylindrical cult objects and ring flower stands. An example of the flower stand (Late Minoan III period) has also been found in Cyprus, where it must have been introduced from Crete. It is of the same date as the Beth-Shan examples. All the various types of peculiar cult objects, other than the figurines of the deities, were unknown in Beth-Shan before the time of Seti I, so it was evidently some of his Mediterranean mercenaries who introduced them. The shrine houses, clay models of places of worship, are something like the houses depicted on certain Cretan faience tablets. Forms of them are also depicted on a Babylonian relief of Gudea, and an Assyrian intaglio of later date. At Beth-Shan the shrine houses were probably used as small stands for special offerings, and the cylindrical cult objects either as incense stands or as vases for sacred flowers or plants. This much we gather from certain Mesopotamian analogies.

The Syrian deities worshipped at Beth-Shan during the time of Rameses II were Antit, Ashtoreth, the Veiled Ashtoreth, Resheph, and a bearded god wearing a conical crown. During the reign of Seti I we find the following deities, Ashtoreth, and Qedesh the holy one, a form of Ashtoreth. During the Tell el-Amarna era they were worshipping Ashtoreth, Qedesh, and Ashtoreth of the Two Horns. Ishtar, the Assyrian form of Ashtoreth, was found on a cylinder seal in the temple of this era. The dove, serpent, lion, gazelle and duck were associated with this Beth-Shan goddess at all periods. Gazelle horns have been found in all the temples. The bull, which was discovered on a vase in association with the lion or emblem of the goddess, was the emblem of a god. The Hebrews themselves seem to have regarded the bull as the symbol of Yahweh. The animal was also the emblem of Hadad, the Syrian god of weather, storms and lightning.

Museum Object Number: 29-107-916

The roofs of all the temples were undoubtedly made of wood. Those over the courtyards of the temples of Seti I and the Amarna era were supported by two stone columns with palm tree capitals. It is quite probable that the local Syrians regarded these two columns as mazzebahs or sacred standing stones and revered them accordingly. The mazzebah and the asherah (sacred wooden post) were generally found in most Syrian high places and sanctuaries. The shape of the columns in the Beth-Shan temples were certainly very appropriate, for the palm tree itself was a familiar symbol of Ashtoreth; and we also find a “Baal of the palm-tree ” (Baal tamar) in a place name in Judges xx, 33. At times the Israelites departed from the worship of Yahweh and set themselves up mazzebahs and asherahs as we see from II Kings xvii (Revised Version). “The children of Israel did secretly things that were not right against the Lord their God, and they built them high places in all their cities. . . . And they set them up pillars and Asherim upon every high hill, and under every green tree; and there they burned incense in all the high places, as did the nations whom the Lord carried away before them. . . . They made them molten images, even two calves, and made an Asherah, and worshipped all the host [i. e., stars] of heaven, and served Baal.”

The actual details of the worship carried out in the Beth-Shan temples must of course always remain unknown, but the wealth of new material which the excavations have brought forth enables us to get a very good idea of the sacred cult of Ashtoreth, the great Lady of Heaven as it was known in Palestine from the XIVth Century to the XIth Century before Christ.