Occasionally we find some article invented by man in a relatively primitive state, with the strain of necessity upon him, of such great perfection that modern ingenuity has been unable to improve upon it. though it may continue to do service either as a useful device or as a means of sport and pastime.

Image Number: 14348

The snowshoe belongs among the devices of this class. Though it has by no means outlived its usefulness, it cannot be considered as a serious factor in the present progress of civilization. The position it occupies is intermediate between the serious work of life and its lighter side of sport. Already in the minds of most people it is associated only with play, an association that seems very much in keeping with an object of such light and graceful structure as the snowshoe. When we repair to our glittering northern winter playgrounds there is nothing to remind us that the snowshoe, indispensable minister to our enjoyment, has played its part in man’s desperate struggle for existence and that it claims a place in the history of the arts of travel and transportation.

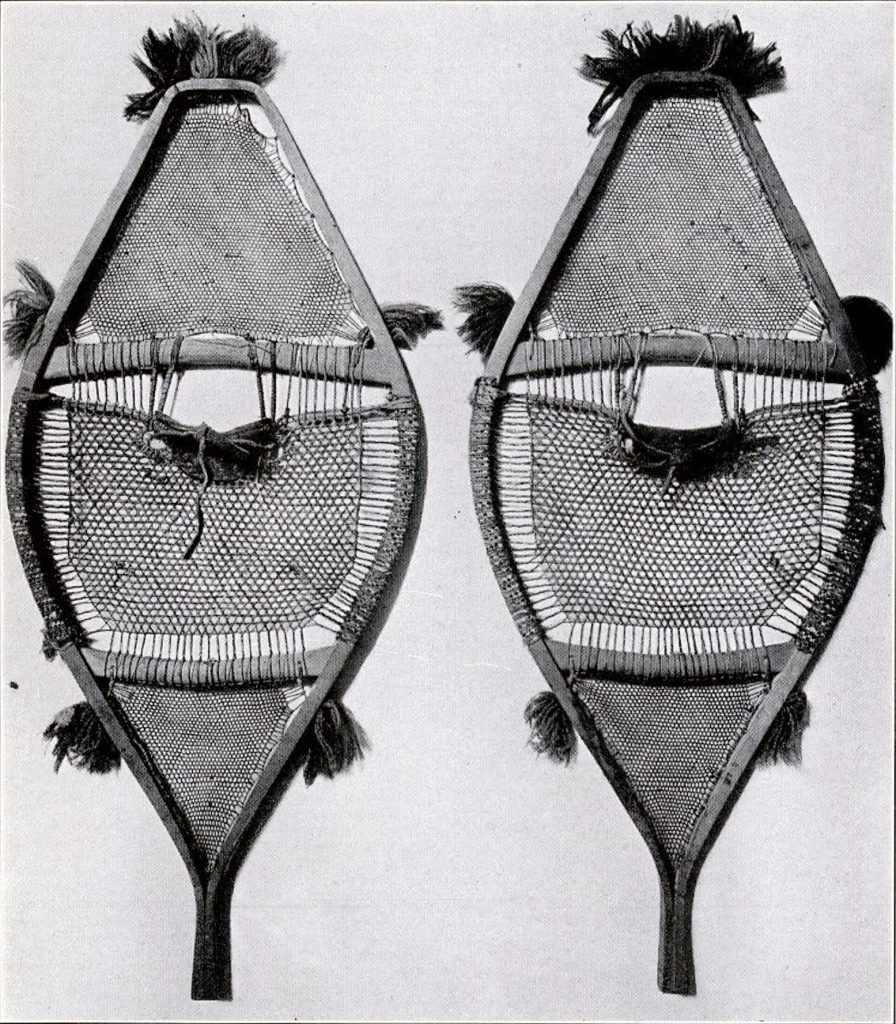

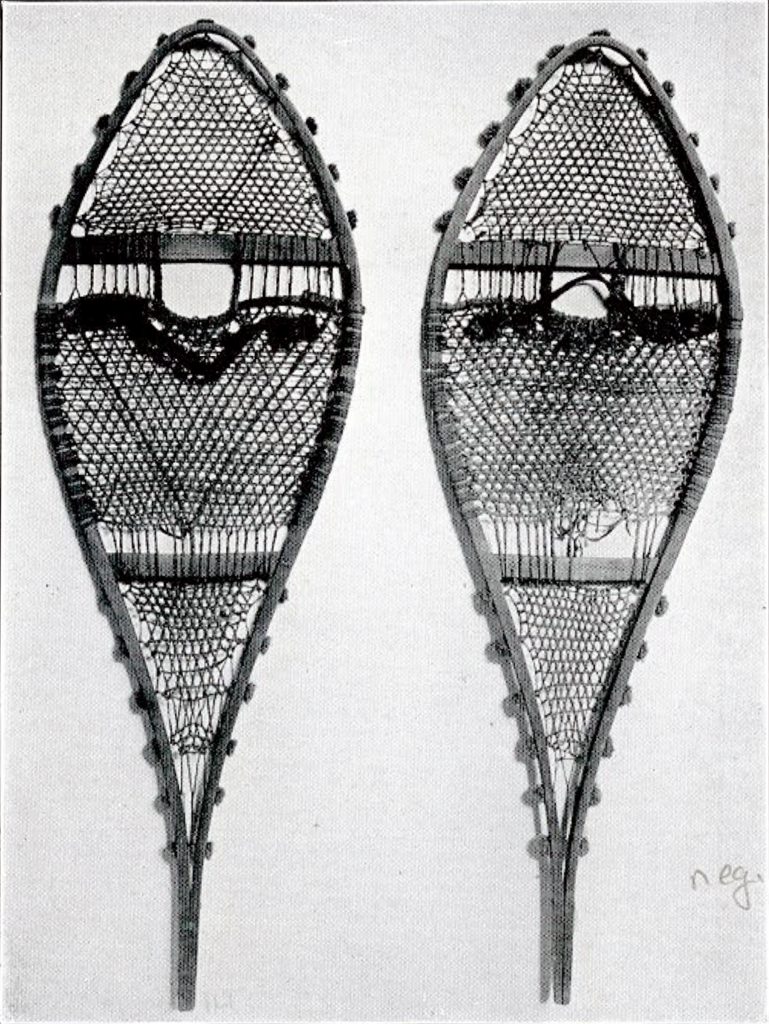

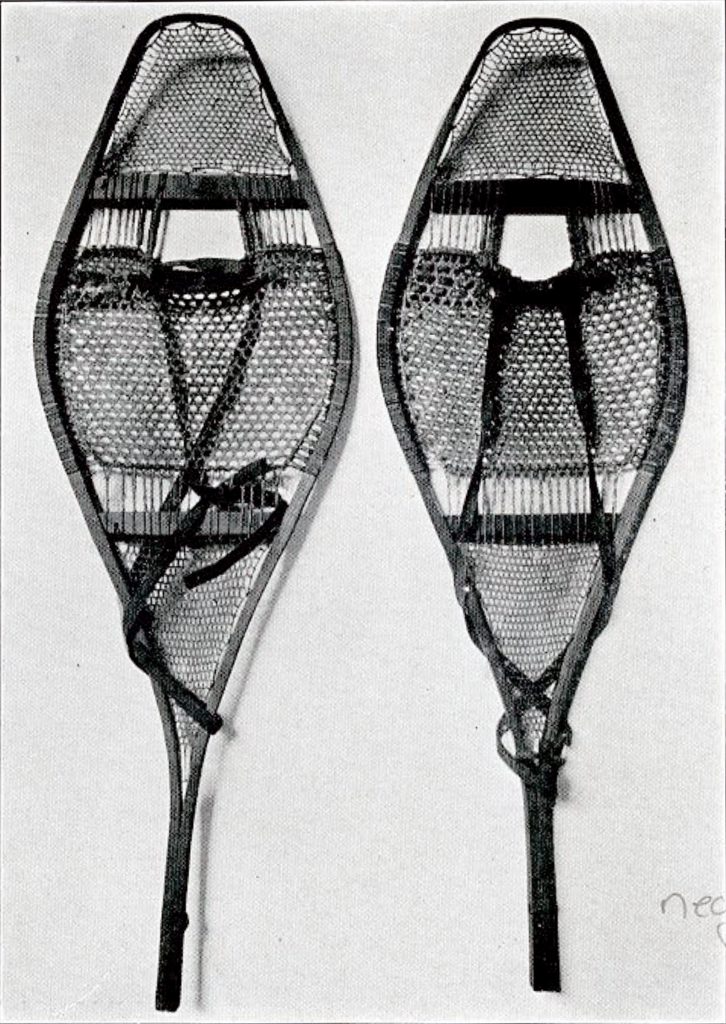

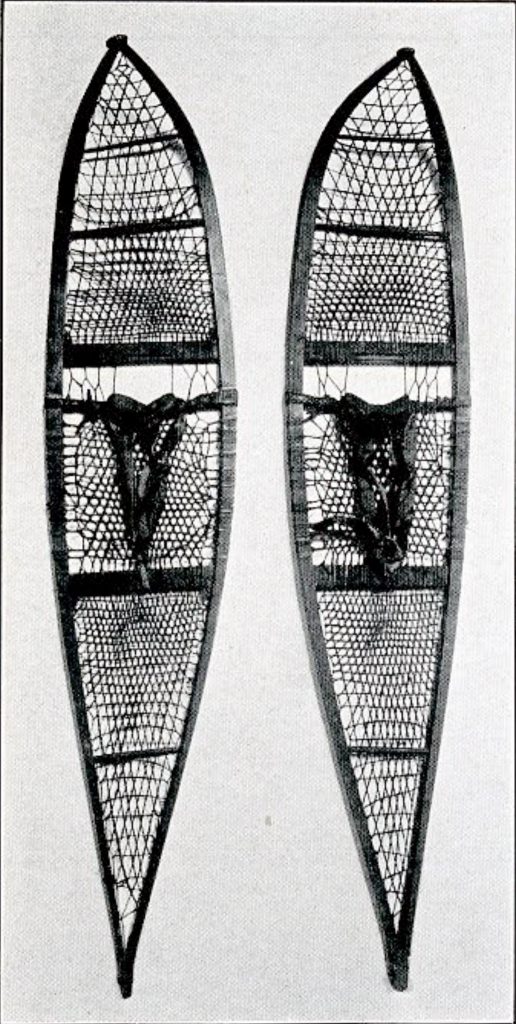

The snowshoe made of a web of meshes stretched on a framework of wood is so characteristic of the North American Indian that it might almost be regarded as his own peculiar property. In no other part of the world except perhaps in Northeastern Siberia did this invention reach nearly the same development as in North America. In so far as the netted snowshoe is concerned that is employed in the United States, it is purely Indian origin and borrowed directly from the tribes of the Northeast. Among these tribes especially, the snowshoe attained a very high state of perfection.

It was devised by the Indian under conditions that made increasing demands on his ingenuity. Perhaps it was in pursuit of game that he first met with the large snow fields, and when he found himself thus confronted he had but two alternatives, to invent something that would support his weight on the yielding snow, or to turn back.

Image Number: 13031

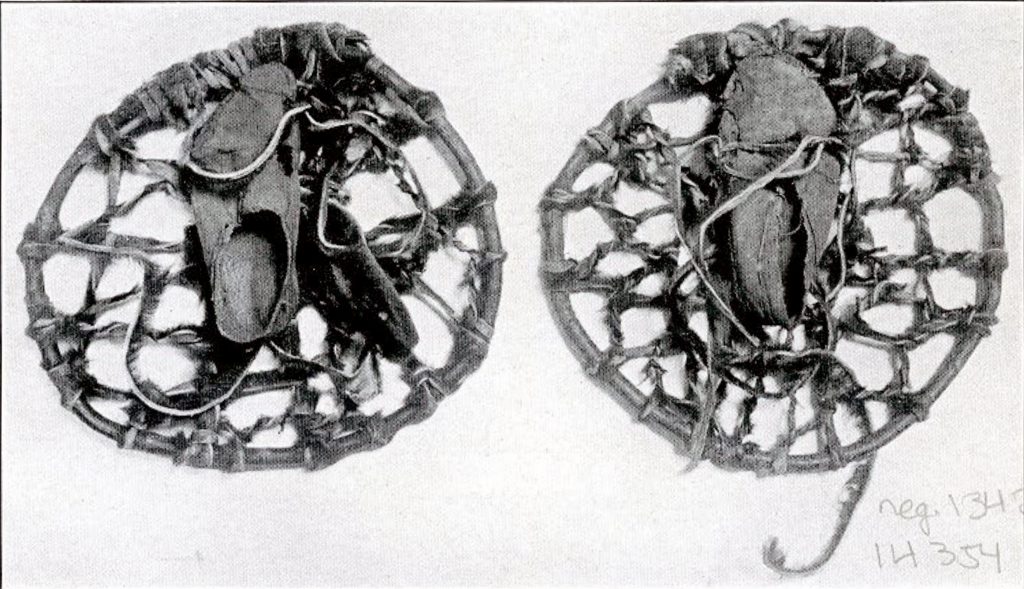

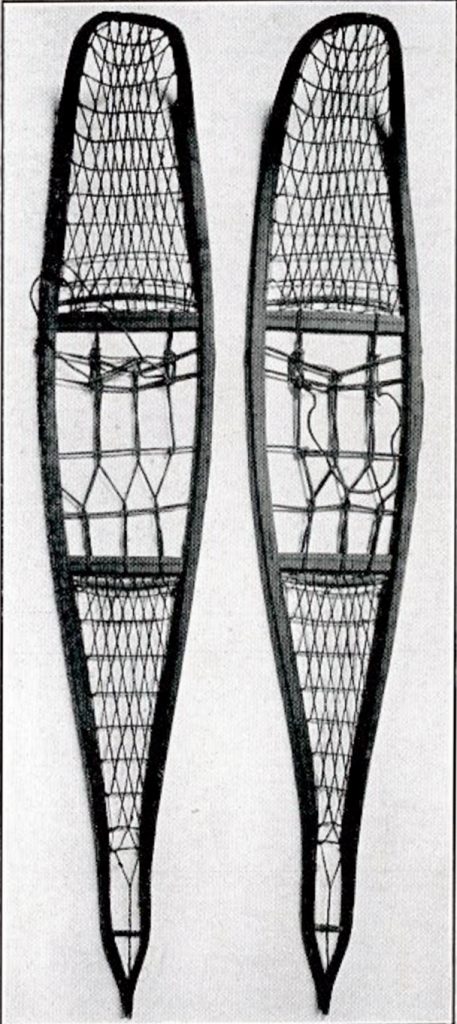

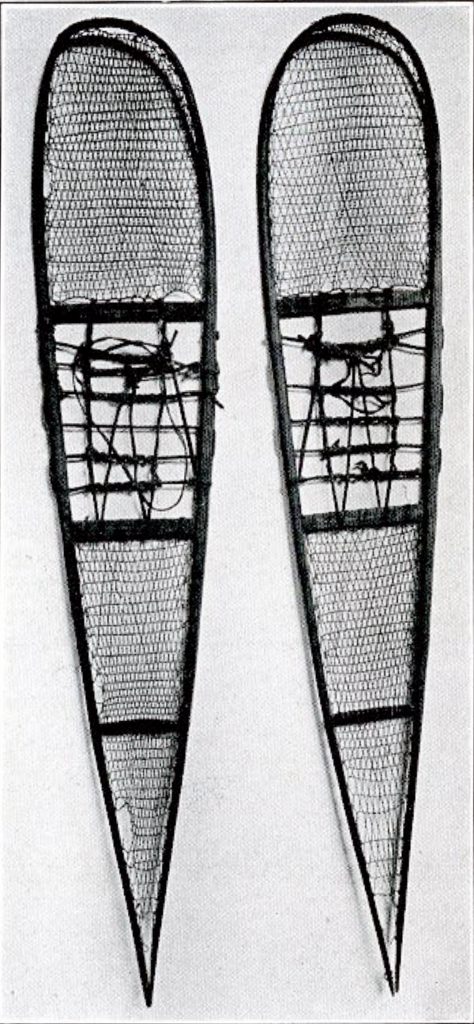

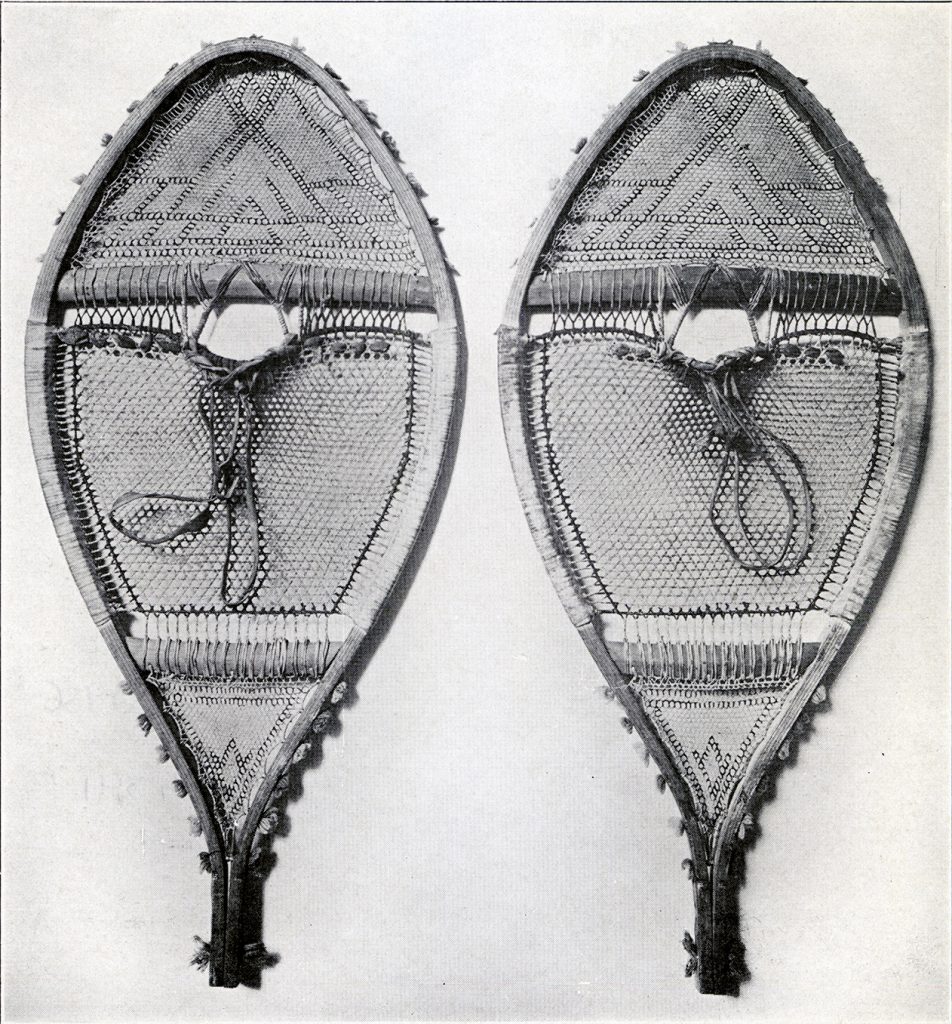

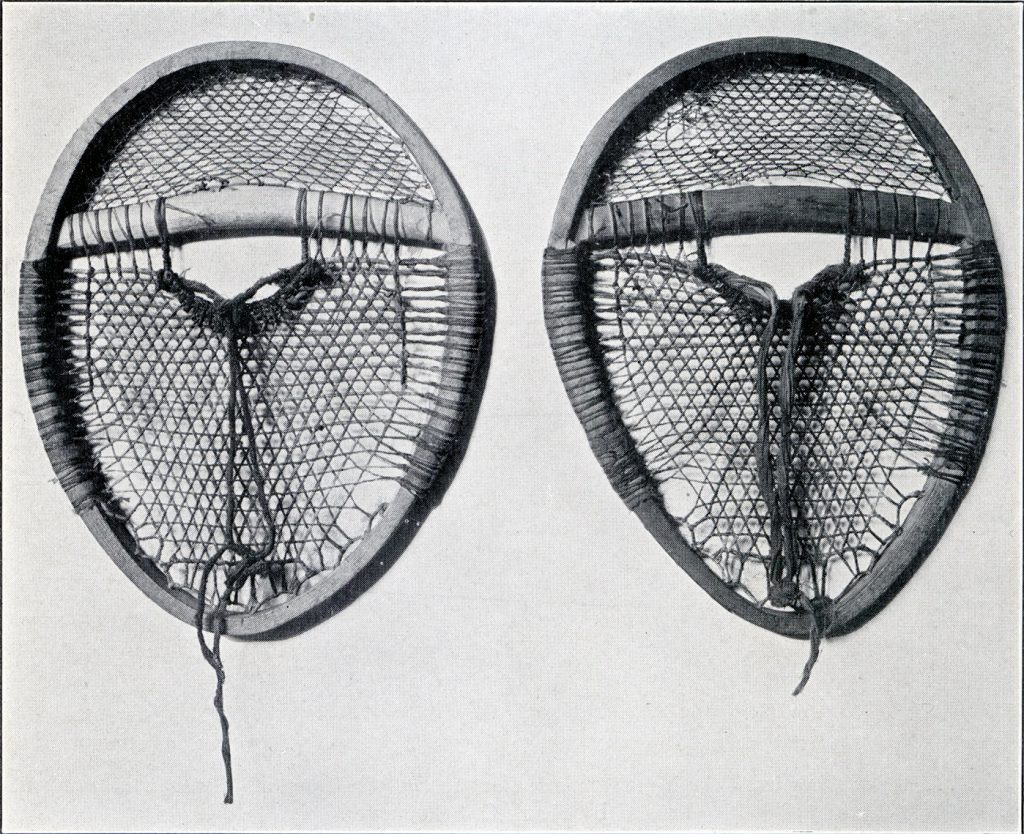

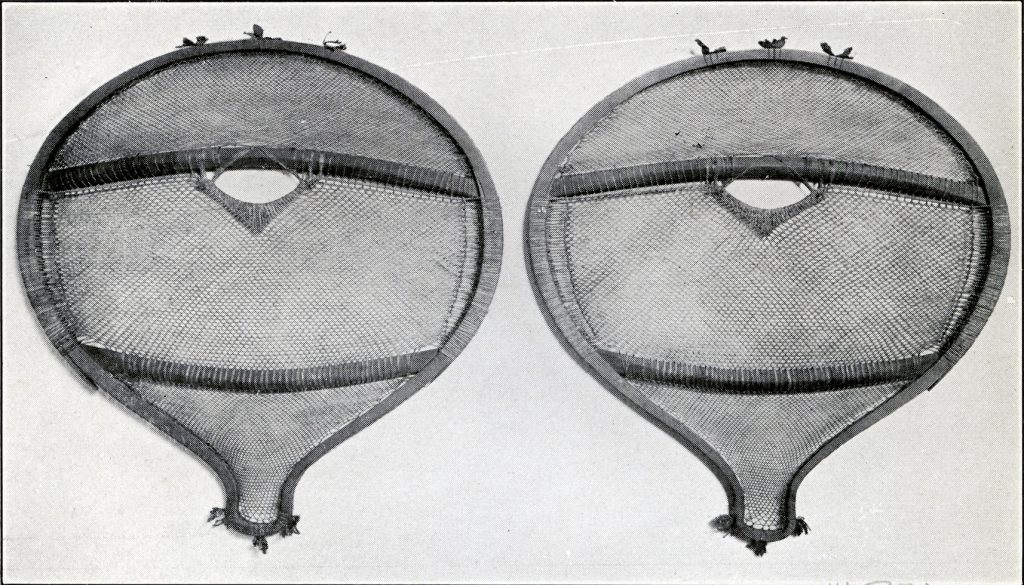

No very intricate device was necessary to distribute is weight on a sufficiently large surface. The difficulty was to find something light enough and small enough so as not to interfere with his motions, and as in all contrivances, it has probably taken a series of inventions to reach the perfection that we now enjoy. Fig. 63 shows a Ute snowshoe, that may not deviate very strongly from the first one made, though we have still cruder examples without any claim to regularity and with only the rudiments of netting. This type of snowshoe is still used by the Piute Indians in mountain climbing and when caught in a snow storm. Fig. 64 shows a type of snowshoes used by the Piute Indians in mountain climbing and rumors say that the owners hold them sacred and take care that they be not polluted by the glance of women, for which reason these shoes can never be taken into camp.

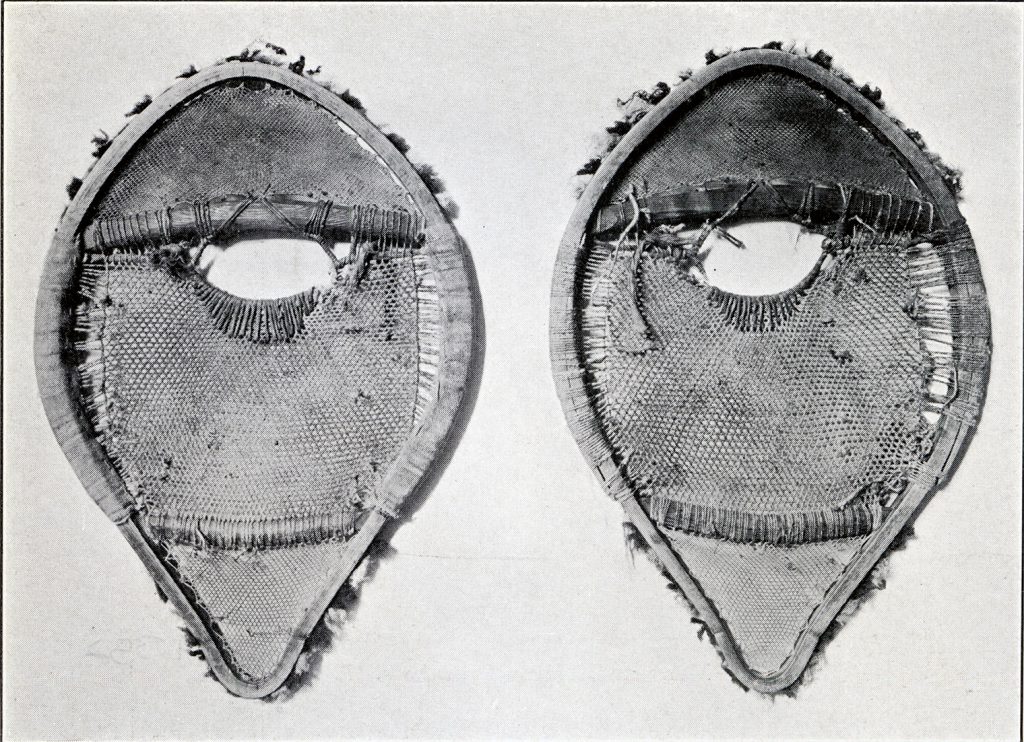

Through the long series shown in the illustrations we may observe a rapid development of intricacy, and of skill in handling the materials. These consisted of a frame of wood, bone or antler, and a netting made of strips of skin. The kind of wood or the nature of its substitute for the frame as well as the particular animal skin employed in the netting, naturally depended on the local supply and therefore on the natural products of the country inhabited by the tribe.

Museum Object Number: NA2101

Image Numbers: 13426b, 14353

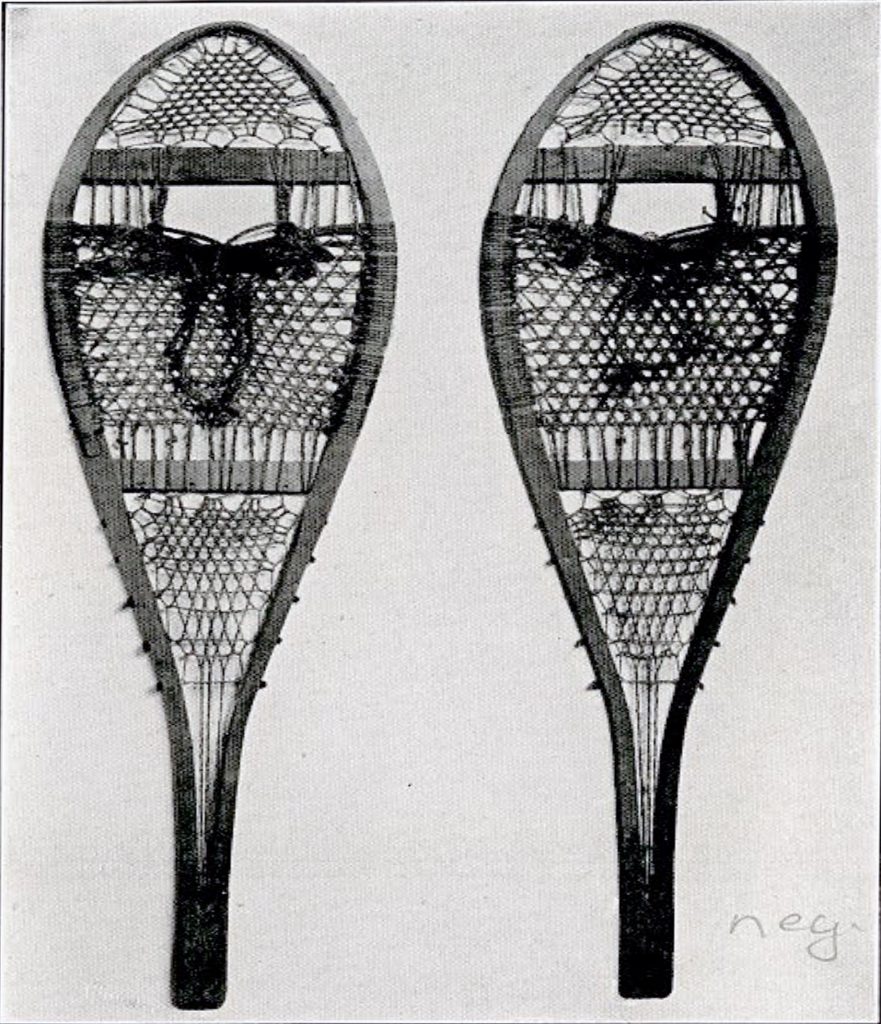

The various snowshoes in the University Museum, ranging in their geographical distribution from Alaska to Labrador and from the mountain tribes to the people of the plains, disclose a number of different technical methods in their construction in the manipulation of the material that make them interesting to the student of man. We can observe, together with a groping after the most practical results, a genuine effort to produce artistic forms, and a well marked pleasure in the playful mastery of technique. The snowshoes of the Hurons and the Montagnais for instance combine in an admirable way the greatest utility and a high degree of elegance.

Image Number: 12816

There is a natural belt for highest development of the snowshoe stretching from the northern part of New York State to within the Arctic Circle. Farther south the snow fall is too slight to serve as a stimulus to a full development, and in the extreme north the snow rapidly freezes and becomes hard enough to sustain the hunter without it.

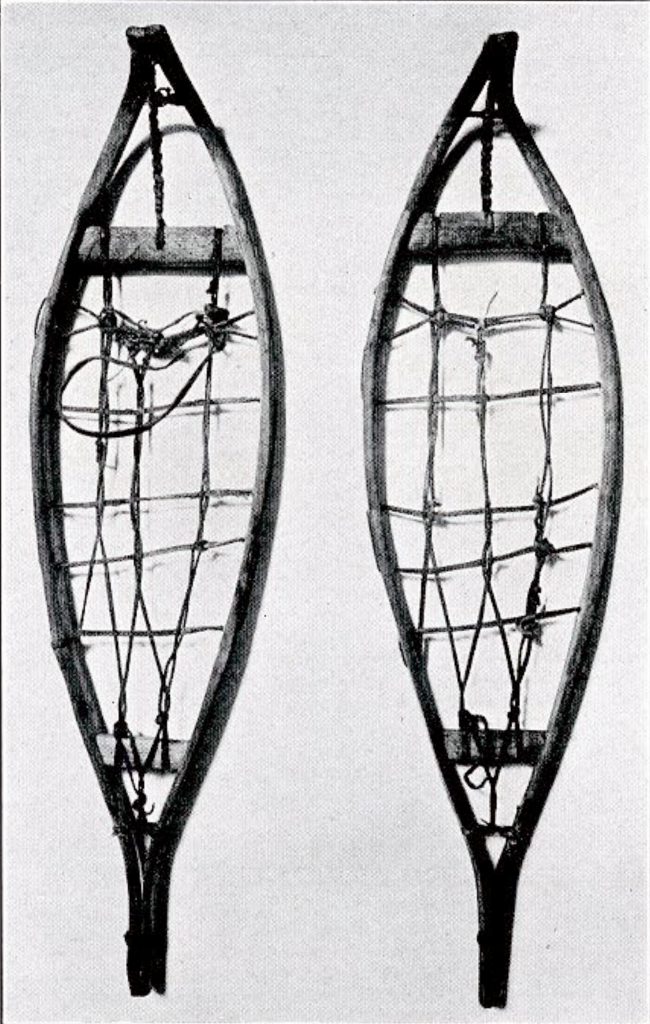

The outer frame or rim is made sometimes in two pieces locked together at the toe and heel. This method is employed by the Alaskan Eskimo and the Northern Athabascan tribes Chipewyan, Louchoux, Kutchin, Khotana, etc.). Among the Algonkians and other eastern peoples however the frame is made of a single piece of wood bent to the approved shape. In either case it is strengthened by cross pieces of wood or stout strips of rawhide. There are usually two of these cross pieces, though occasionally only one is used, and in some types the number is increased to four. In applying the babiche to the framework the Indian has displayed much ingenuity and in the articles of finer mesh has shown his fondness for decorative effects.

In the spring of the year, when the snow melts, the netted snowshoes become clogged with slush, which renders the weight fatiguing. Wooden snowshoes, well suited for this season of the year, are then sometimes substituted.

Throughout the north, from the Micmacs of the Maritime Provinces to the Naskapi of Labrador and the Eskimo of Alaska, southward to the latitude of the Great Lakes the snowshoe is made after different models, each tribe following its own approved pattern. Definite types prevail in each tribe and thus it becomes an easy matter to identify any tribe from its snowshoe. Some varieties are, however, found in common throughout the whole area. A closely woven mesh is best for dry, powdery snow, a coarser mesh for crusted surfaces, a long narrow frame with upturned prow is better for tracking or running in a level open country, while a flat broad frame excels in mountain journeying, or traveling through forests.

In the University Museum collection are a number of types and varieties of snowshoe which show its distribution and specialization. Unquestionably the finest specimens come from the northern Algonkians (Naskapi, Montagnais and Penobscot), and from the Hurons. All these tribes inhabit a country where the deep snows of winter caused the Indians to attain a high degree of excellence in their means of winter transportation. Even the Eskimo, in a more truly arctic region, have less need of perfecting the snowshoe because with them the fallen snow does not lie as deep, nor remain as soft as in the subarctic latitudes. In the prevailing the Naskapi and Montagnais or Labrador type, known popularly as the “beaver-tail,” the frames are of spruce and the netting of caribou rawhide. Farther south in less mountainous territory dwell the river tribes, the Malisits of New Brunswick, the Penobscots of Maine and the Hurons and Abenakis of Quebec. The snowshoes of these tribes are longer, narrower, and have lengthened tail-pieces of trailers. Those of the Northern Athabascan tribes are still longer and narrower with upturned prows. All of these peoples use a bone or wooden netting needle about three inches long tapering at both ends with the eye in the center. It is one of the interesting sights of Indian village life in the north to see the men filling in the network of the frames and passing the time with smoking and story telling.

Image Number: 14358

The snowshoe is attached to the foot by means of an ankle loop and a toe thong. The Indian readily puts them on without the assistance of his hands, slipping his foot through the ankle loop and adjusting the toe thong by a swift and dexterous movement of his moccasined foot. The method of attachment leaves the heel entirely free, the weight of the shoe as it is lifted and brought forward at each step being borne by the toe. Thus the prow of the snowshoe only is raised at each step; the heel is left to the trail along the snow. In traveling over the snow the Indian walks with a long swinging gait and swaying motion of the body.

To the welfare of hyperborean peoples generally snowshoes are absolutely necessary. They could not procure food without them. They could not procure clothes without them, because the animals that furnish these people with furs must be captured in winter, and the ground to be hunted is of great area. So some of these northern tribes go out in the fall and build their birch bark houses wherever the hunting ground seems promising, and when the north wind sweeps down over their country, and their faces and fingers freeze almost stiff on the bleak winter day, they have to outface these difficulties or go hungry. Many a storm has tried their vitality and no one has kept count of those who were defeated in the struggle for existence before the return in the spring. It is under these conditions that the snowshoe does its service to man and under these conditions it has had admirable development.

Image Number: 14357

In Europe the invention that corresponds to the American snowshoe is the Norwegian ski. The relative merits of the two are often debated by those who are accustomed to use the one form or the other, and each has its advocates.

There is no doubt that the long, swift, upturned wooden runner lends itself to performances of a kind for which the American snowshoe is by no means adapted either by design or by practice. In open country the ski has advantages over the snowshoe, and especially on sloping ground, where the straight, smooth runner allows the sportsman to perform those long glides and those extraordinary flying leaps in which he launches himself into the air from the take-off for a jump of 50, 75 and even 135 feet. The last distance mentioned is the record jump, the others are common enough. The record time in racing with the ski is 15½ miles in 2 hours and 7 minutes, over open, level country.

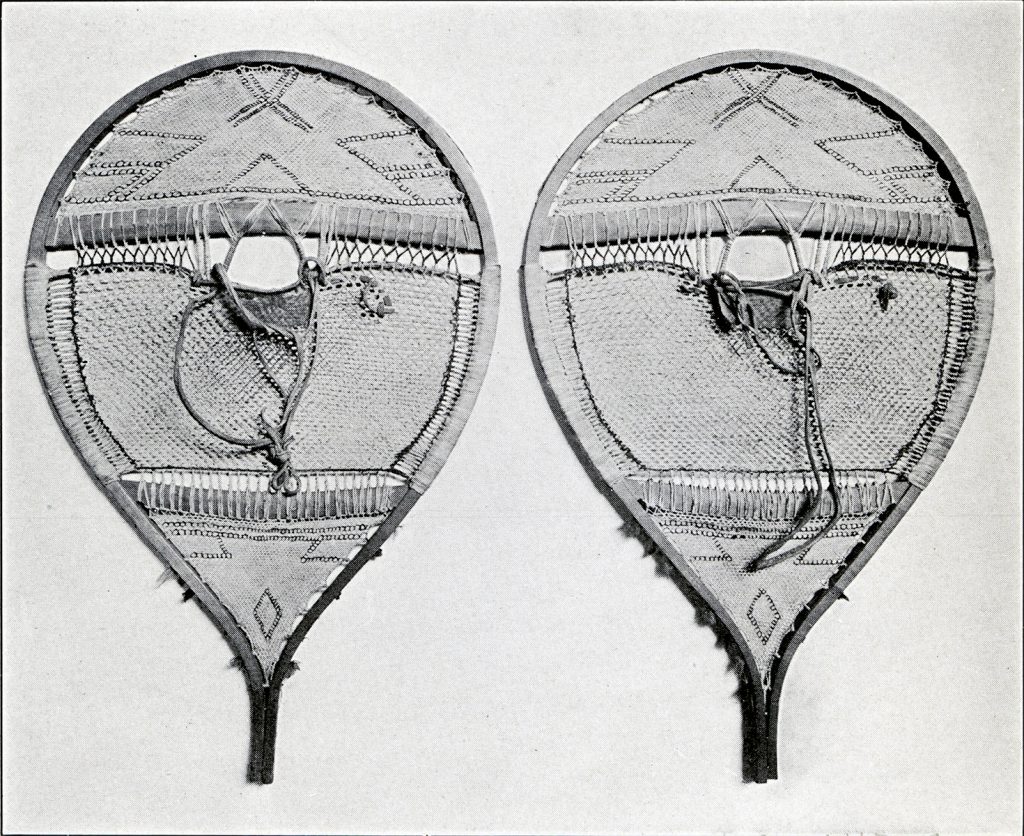

But compared with the Indian snowshoe the ski is unwieldy, and for tracking through timber or over loose snow all authorities are agreed that the snowshoe is very superior to the ski. In the American snowshoe, moreover, the qualities of lightness, strength, gracefulness, ingenuity of construction, and facility in use, are combined to make it an article of special merit, remarkably adapted to its purpose. As though not content with this achievement the Indian essayed, in the more perfect examples, to render his workmanship still more attractive to the eye and more pleasing to the mind by working into the fabric of the mesh, a decorative pattern which exhibited at once his desire to please and his skillful mastery of technique, an exercise of his faculties in which the Indian craftsman took special delight. Examples of this form of decoration may be seen in Figs. 73 and 77. Or he embellished the wooden frame with tufts of dyed moose hair, or colored worsted after the manner seen in Figs. 61 and 67.

Image Number: 12986

Although it is quite true that the racquet form of snowshoe is to be assigned in its development to the American Indian and although the ski is of Scandinavian origin, both ‘types are now widely used by different peoples. Both forms are best known in connection with sport, but in France and in Italy the ski is employed in military maneuvers, and in the Andes it is used by mail carriers. In Canada the snowshoe is used by the Royal Northwest Mounted Police, by fur traders, trappers, couriers, and travelers who have occasion to traverse in winter the vast tracks that are still remote from railroads and other more modern methods of communication.

In Canada the snowshoe club contribute largely to the interest in snowshoeing as a sport and serve to stimulate the practice of this pastime. Snowshoe racing forms one of the principal sports of these Canadian clubs.

Other forms of snowshoes have been used historically by different peoples of the world. They were usually made of skin, and in Ancient Greek literature we are told that the horse of the Armenians were equipped with snowshoes of this kind.

Image Number: 14343

Image Number: 14342

Image Number: 14341

Image Number: 14345

Image Number: 13033

Image Number: 13034

Image Number: 13032

Image Number: 14352

Image Number: 14351