The Amazon River has challenged exploration since the men who conquered Peru passed over the Andes and launched their improvised craft on the waters that led them to the Atlantic. To the Spanish and Portuguese adventurers of the sixteenth century the greatest river system in the world was not unknown, yet to-day its shores present for the most part an unbroken forest.

Image Numbers: 140882, 20838

Though such names as Bates, Wallace, Marcoy, Coudreau and Agassiz are forever associated with the history of its exploration, especially on account of their contributions to the natural history of the Amazon, the great wilderness has not been conquered. These men and others who, for the last four centuries, have followed its course from the Andes to the Atlantic and traced many thousand miles of its affluents could only guess what lay beyond the gloomy forests on the shores. Their observations were confined to the river itself. To go one hundred yards from the margin of the stream to-day at almost any point is to enter unexplored country and whoever continued such a journey would soon be swallowed up in the wilderness and lost to the world.

Image Number: 41285

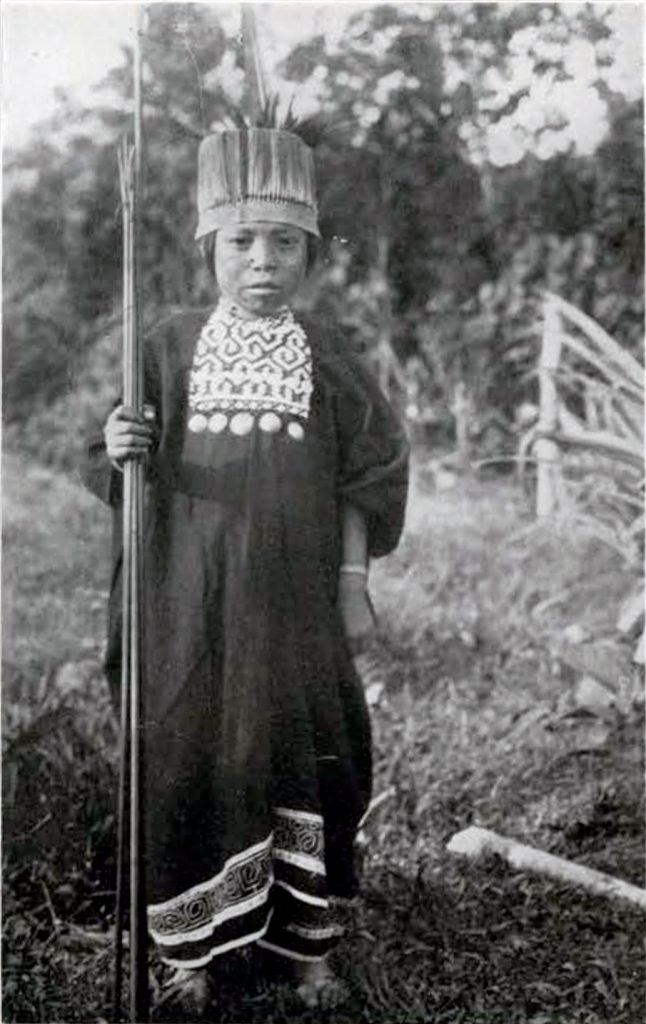

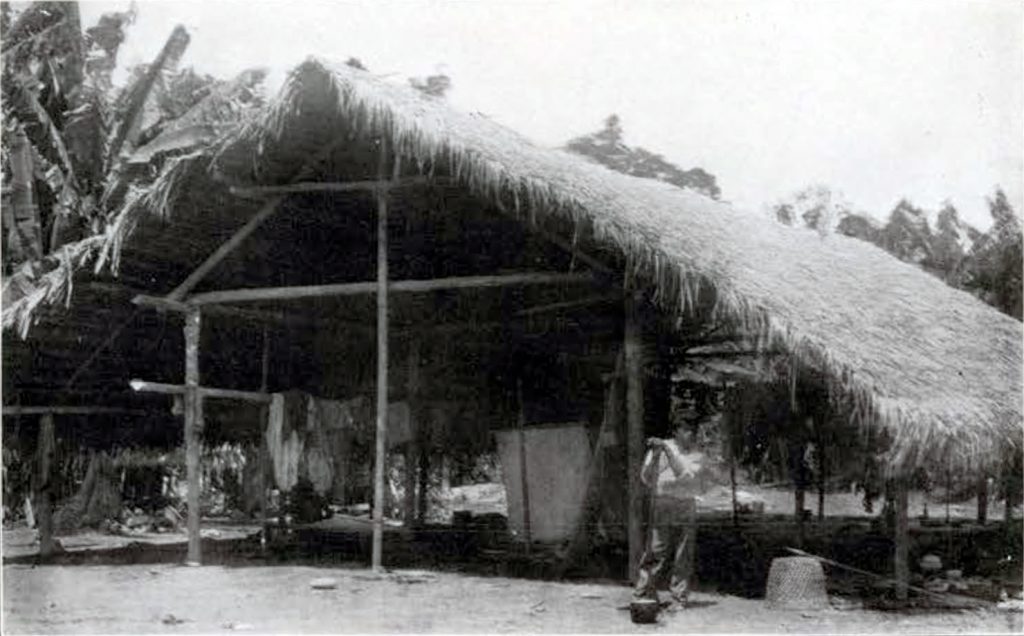

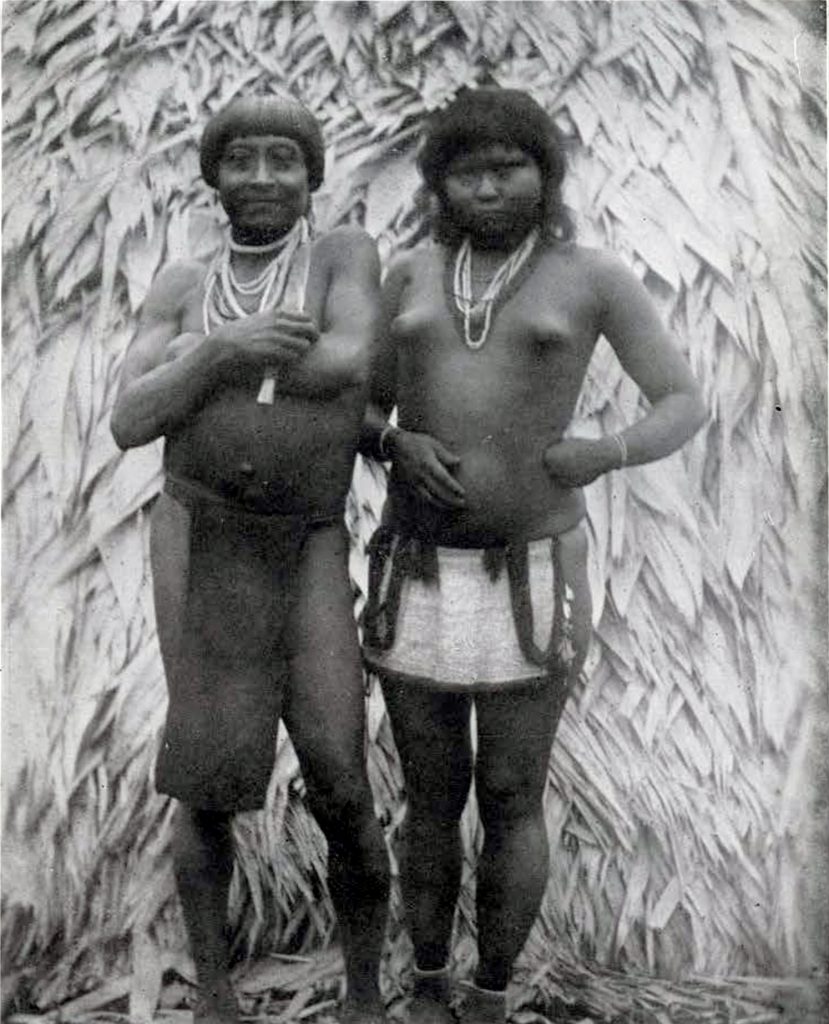

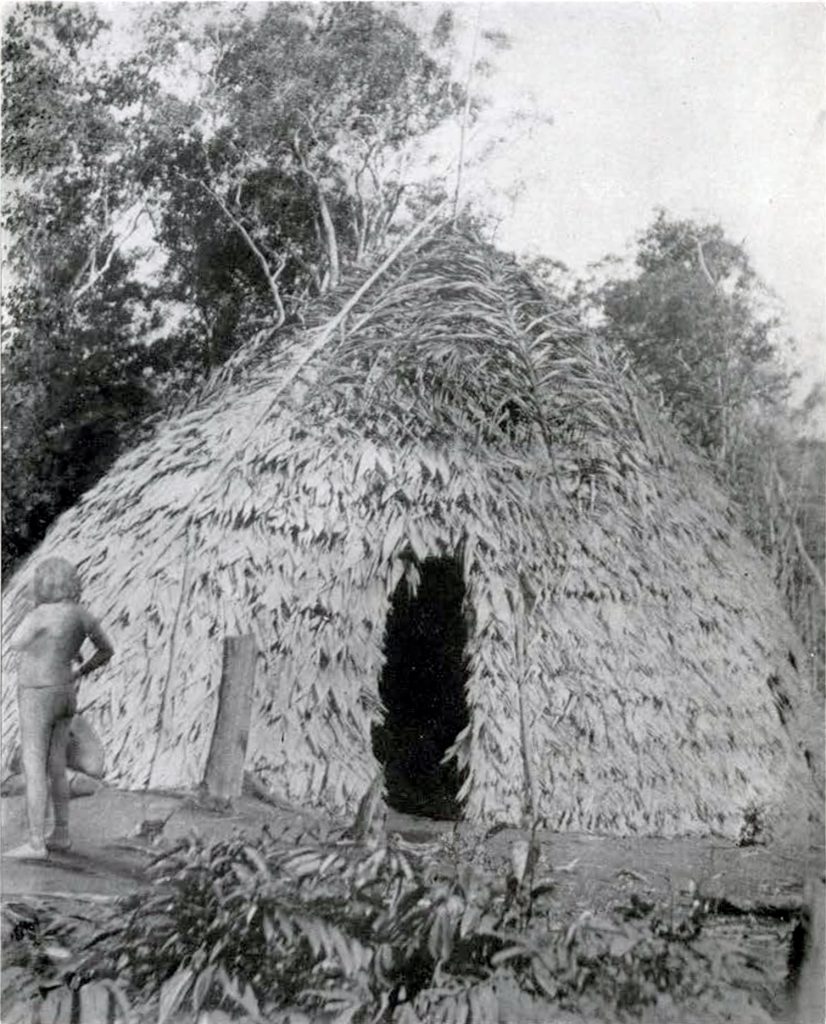

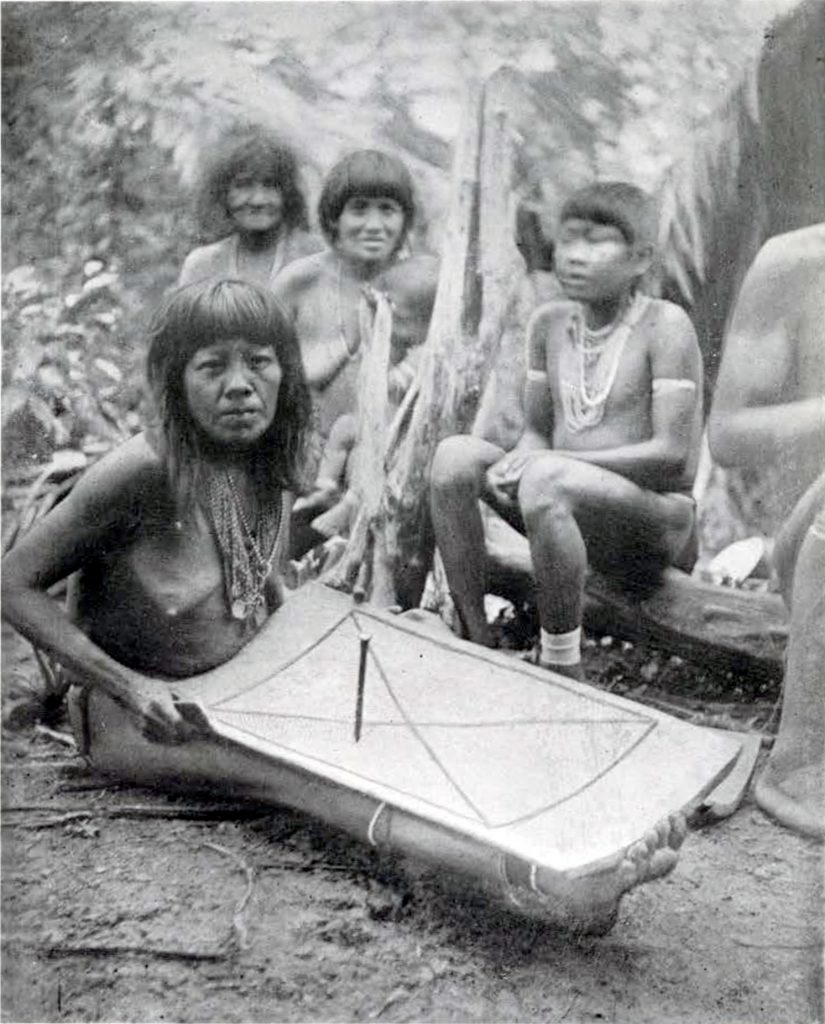

The branches of the Amazon reach out into the last large unexplored area of the earth’s habitable surface. In forests where the rumors of civilization have not yet reached and where the feet of white men have not made a pathway, the aboriginal peoples still live unseen their primitive lives. So far as we are able to form any opinion of these isolated inhabitants of the earth, they are peaceful and often so timid that the appearance of strangers is a signal for their flight. They are picturesque in the extreme and live entirely on the natural products of the forest. They are without knowledge of agriculture, yet in many of the arts of life they present great skill and many of their social customs often show an elaboration of savage art and practice quite remarkable.

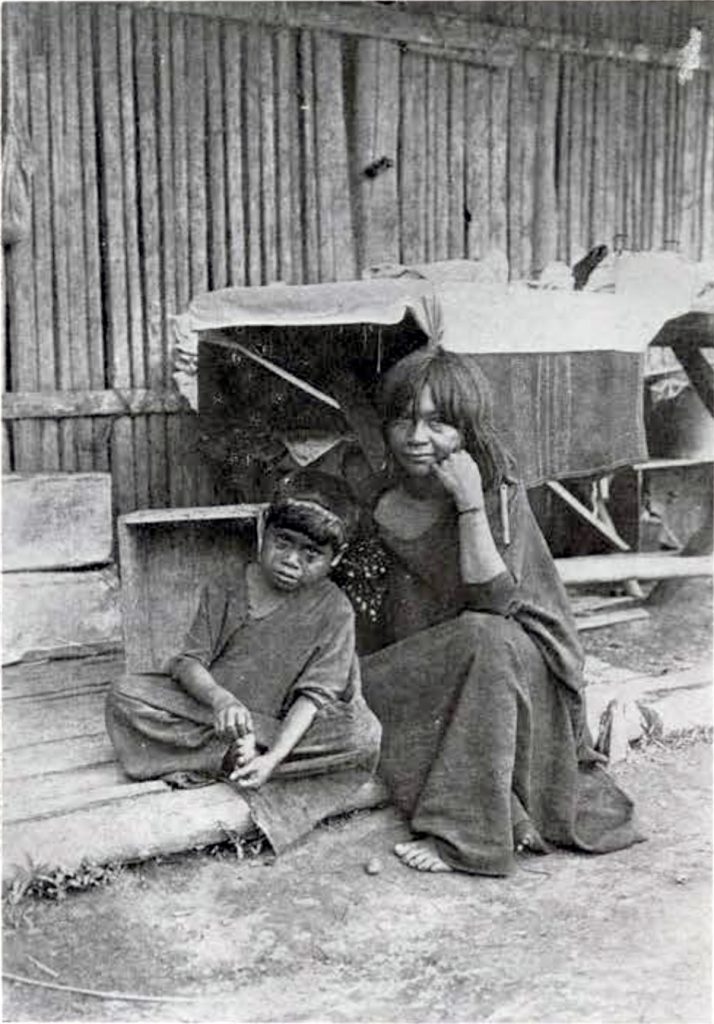

The less fortunate Amazonian tribes that live on the fringe of civilization where the rubber gatherers have built their towns and established their depots, have quickly borrowed foreign habits and invariably show a tendency to abandon their native arts and modes of life. The regions that still remain remote from these persistent influences are becoming gradually less, and the present impetuous search for rubber is bringing all of the tribes nearer and nearer, if not to destruction, at least to obliteration of the ways and works that make them different from other men.

To reach the tribes that still remain in their primitive condition in the forests of the Amazon is a plan which the University Museum has been considering for more than a year. The undertaking presents many difficulties, for the climate is a particularly trying one, fevers are prevalent, the distances are great, the forests are difficult to penetrate and the human inhabitants of these forests are often as shy as the wild creatures which they hunt. In order to cope successfully with these conditions a steamer was provided at the outset for the service of the expedition, to provide the means of caring for the health and comfort of the members and serve as a movable base from which extended explorations could be carried on. The expedition sailed from Philadelphia on March 19th. On reaching the Florida coast it was found that the yacht needed repairs. As these repairs required considerable time to effect, Dr. Farabee, the leader of the expedition, decided to proceed at once with Dr. Church to Para, and thereby avail himself of an opportunity of studying at closer range the field of operations that lies before him and the problems which the expedition will have to meet. At the same time, Dr. Farabee arranged that repairs on the yacht “Pennsylvania” should be completed, after which she should return to Philadelphia, there to await further orders.

Meantime, the Brazilian Government, through the State Department in Washington, have expressed their active interest in the expedition and have offered to give Dr. Farabee and his associates every assistance within their power.

From Para the expedition will proceed to Manaos; from thence it is proposed to ascend the Rio Negro, the largest tributary which comes into the Amazon from the northwest. The first labors of the expedition will therefore lie in that direction. On the upper waters and on the branches of the Rio Negro live numerous tribes of which little is known. These tribes will probably occupy the attention of the expedition for six months or perhaps a year.

Image Number: 153752

The collections to be made will consist of weapons, utensils, ornaments and all objects relating to the arts of life, which will be found among the various tribes visited. They are destined to supply material for future research and especially to enable the Museum to reproduce for the public benefit, the actual life of some of the most picturesque peoples now inhabiting the earth, but soon to disappear. Such an exhibition, together with those from North America already in the Museum, will form a truthful and permanent record of the first Americans.

While the program of the expedition is subject to change, a general scheme has been laid down from the outset and the main objective points of these explorations will remain unaltered. The regions which especially invite investigation are the following: the highlands lying along the borders of Brazil on the one hand and British and Dutch Guiana on the other; the region drained by the Araguaya and the Tocantins, the upper waters of the Rio Negro and its branches the Rio Branco and the Uaupes, the Ucayali, and lastly the regions lying between the Madeira, the Purus, the Tapajoz and the upper Xingu. The ethnological problems presented by the natives of any one of these regions are sufficient to engage the attention of a group of ethnologists for an indefinite period and the main work of the expedition will be confined to the parts where the most favorable conditions are met with. What the Museum especially hopes to do during a three year period of exploration is to pave the way for a more intimate knowledge of some of these primitive peoples and to bring the country which they inhabit into closer touch with scientific inquiry. This exploration has its dangers and its risks; its cost is difficult to reckon and experience is all to make, but the ends to be attained are so important, the scientific interests at stake so great, that it seems to be worth an effort.

Notable ethnological work has recently been done in some of the regions mentioned, chiefly under German and American auspices. One of the most notable of these explorations was done by the de Milhau expedition of Harvard University, of which Dr. Win. Curtis Farabee was the leader. This expedition entered the country from the Pacific coast and after crossing the Andes reached the upper waters of the Amazon. Having been chosen as leader of the University Museum Amazon Expedition, Dr. Farabee will this time enter the field of exploration from the opposite direction. He will, for the most part, be covering new ground, but, at the same time, will be dealing with conditions with which he is already acquainted.

Dr. Farabee is a native of Pennsylvania and received the degree of Ph.D. at Harvard, 1903. Since that time he has been continuously engaged in teaching and in special scientific work at Harvard University. In January, 1913, he was appointed to the position of Curator of the American Section of the University Museum.

Image Number: 173849