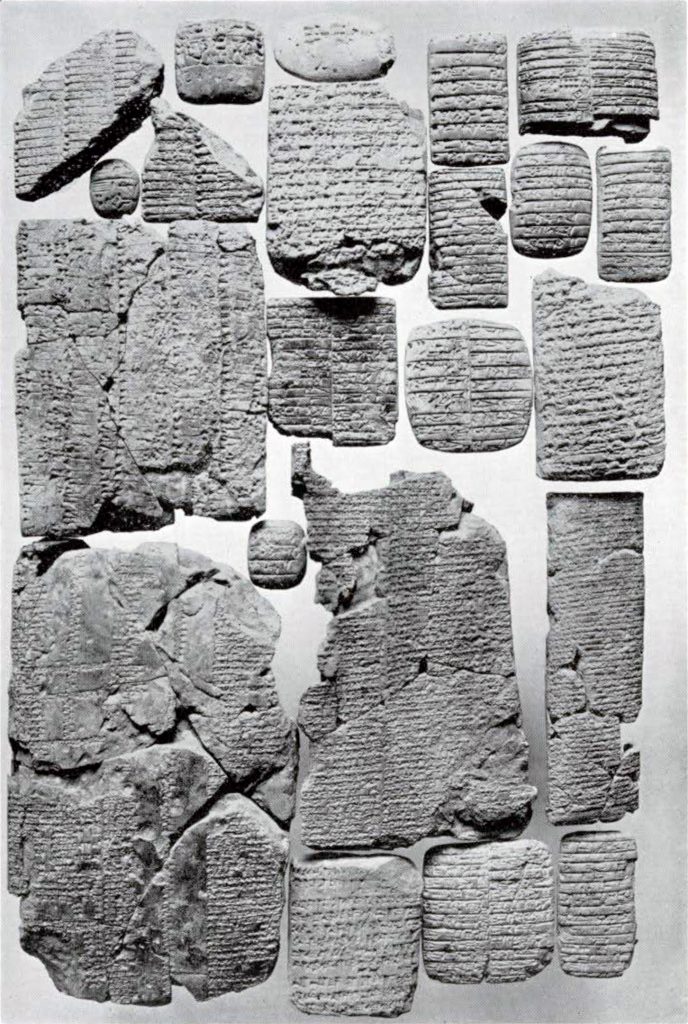

In the spring of 1910 one hundred and fifteen boxes of inscribed tablets and fragments of tablets, excavated by the University of Pennsylvania Babylonian Expedition at Nippur during the years 1888-1900, were unpacked in the workrooms of the Museum. Since that time trained assistants have been engaged in the laborious task of cleaning these tablets, assembling the fragments which belonged originally to the same tablet, putting these together, and securing the proper preservation of the collection. Between 1888 and 1910, 6,970 tablets and fragments had been examined and catalogued. The estimated number which came from the boxes unpacked in 1910 is 10,000. The collections of Babylonian tablets in the Museum therefore number about 17,000. A large proportion are in many pieces, and fragments of the same tablet are often found in the contents of different boxes. This, and the fact that the clay from which they were excavated, adheres to the tablets, together with other matter with which they were brought in contact in the packing, makes the cleaning and mending very slow work. The assistants who are engaged in this work, not being versed in the cuneiform writing, are guided by correspondence of fractures, general similarity of writing, or of color and texture in the clay in bringing fragments together which belong to one tablet. In this way many pieces are sometimes brought together and a tablet more or less complete built up from pieces of varying sizes.

Since they come as often as not from different parts of the box and often from different boxes, there are only two methods of assembling the fragments. One is the method already described, and the other is by means of context in the inscription written on the surface of each tablet. This latter method can be used only by those who read the cuneiform text. After the trained assistants have exhausted the resources of the first method it sometimes happens that a Babylonian scholar discovers in reading the inscriptions that two apparently distinct pieces actually belong to the same tablet.

After being cleaned by means of soft brushes and other methods devised to avoid injury to the tablets, a lot of fragments, large and small, are spread out on long tables, and the work of discovering the pieces that belong together proceeds until no more joints can be made. Each tablet is then packed separately in cotton and placed in receptacles which are kept in rooms with dry atmosphere and even temperature, for these tablets are often of unbaked clay and being impregnated with certain salts are apt to disintegrate under unfavorable conditions.

The important considerations which have been kept in mind in connection with this work from the first are to secure the preservation of the tablets with special reference to their scientific and historical value, and to make them accessible to Babylonian scholars in order that such facts of importance for human history as may he contained in these ancient writings may find interpretation and become matters of general knowledge.

Babylonian scholars everywhere have been invited to avail themselves of the opportunity which these tablets afford for the investigations in which they are interested, and the collections have been placed at their disposal with proper facilities for their study. Among the scholars who have taken advantage of these privileges is Dr. Arno Poebel, of Johns Hopkins University, who spent five months during the summer of 1912 in the Museum copying tablets which he selected to form a volume of historical and grammatical texts. Dr. Poebel copied and translated about two hundred pieces of text, some of which are of great interest.

In the article which follows, Dr. Poebel gives for the benefit of the readers of the JOURNAL, some of the more interesting results of his work.

G. B. G.

Image Number: 206362