The President of the Museum, Mr. Eckley B. Coxe, Jr., has recently presented to the Museum Library a copy of the Description of Egypt published under the patronage of Napoleon and growing out of his Egyptian campaign. Mr. E.P. Wilkins has kindly contributed the following descriptive notice of this work for the JOURNAL

—Editor.

My attention was recently called to the copy of Napoleon’s Egypt acquired by the Library of the University Museum. Upon examination my interest was aroused by the fact that this proved to be the only perfect set of the first edition that I have ever had the good fortune to see. It was then that I made some investigation of the history of this important and monumental work with a view to finding the reasons for the varying merits of different copies. It may be interesting to the readers of the JOURNAL to recall something of this history.

Napoleon’s Egypt, so-called from the fact that it represents the scientific results of Napoleon’s Egyptian Expedition in 1798, takes rank as the first great work which revealed to the world the treasures of Ancient Egypt. From the publication of this monumental work dates the real beginning of the long line of scholarly productions which have added to our knowledge of Egyptian civilization, Before its publication in 1809, the remains of Ancient Egypt were known only through the hasty notes of travelers, or at best the passing notice of explorers who, like Bruce, 1768-1773 (seeking the sources of the Nile), had other objects in view. Before the summer of 1798 no systematic exploration of this immense storehouse of antiquity had ever been undertaken.

ORIGIN OF THE WORK

When Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition was organized, the very unusual and elaborate preparations of its commander gave rise to much speculation. It soon became apparent that it was something more than a mere army of conquest. There was organized an army to fight battles and besiege cities, but there was also equally well organized a select company of eminent scholars and artists, nearly a hundred strong. Once landed on Egyptian soil this two-fold expedition began to operate and to justify itself. While the army was winning victories and magnifying the fame of Napoleon, this little company of scholars was uncovering the ancient civilization of Egypt. Vivant Denon, an enthusiastic member of the expedition, an artist and traveler, noted in his day for his finished and scholarly productions, published an account of their labors in 1802 after his return to France. His vivid and interesting narrative enables us to appreciate the difficulties and problems which confronted them, laboring in a hostile land, surrounded by enemies, in the midst of frequent alarms and the smoke of battle. We may still marvel at the magnificent results which they obtained by unremitting toil, to present to the world in one of the greatest archaeological works ever published.

The fate of this brilliant military enterprise is too well known to need relating here. When the end finally came and the “Army of the East.,” abandoned by Napoleon, was withdrawn (1802), strenuous efforts were made by the French general to preserve the collections of natural history and antiquities. But General Hutchinson was inflexible and insisted on the delivery to the British of all objects in dispute in accordance with the terms of capitulation. He finally agreed, however, to allow the naturalists to retain their collections entire, but he would not extend the same courtesy to the archaeologists and artists. Hence all collections of ancient manuscripts and antiquities were turned over, including the greatest find of all, the famous Rosetta Stone. This, of course, was a prize the value of which was too well known to escape the keen eye of the English general. On its delivery to the British (1802) it was immediately sent to England, where it soon found a resting place in the British Museum along with the other “spoils of war.” But, nevertheless, it remained for French scholarship to unravel the hieroglyphics by the aid of the three-fold inscription on the stone. The three inscriptions are represented natural size in Napoleon’s Egypt, Antiquités, Vol. V, plates 52, 53 and 54.

In 1805 a commission of eight was appointed to collect for publication all the memoirs, monographs and designs of the various members of the expedition, the entire cost to be borne by the state. The publication was to be in fact the scientific results of the Egyptian expedition. Four years later, in 1809, appeared the first instalment of the great work, consisting of a volume of introductory matter, three volumes of plates and three volumes of text, under the general editorship of M. Jomard. The publication was continued at intervals until 1822, when the last instalment was issued.

No greater tribute can be paid to the scholarship which produced this work than the following quotation from an English Journal of 1854: “By its care for scientific and literary interests, the mind of France conquered even when the sword fell from her hand. France brought back a pure and a permanent conquest from Egypt—a conquest unsullied by a crime and undimmed by a tear. The labours of her learned commissioners on the Nile will continue a portion of her intellectual empire to the end of time. No disaster can ever rob her of that glory—so worthily won and so modestly worn.” (Athenæum, April 1, 1854.)

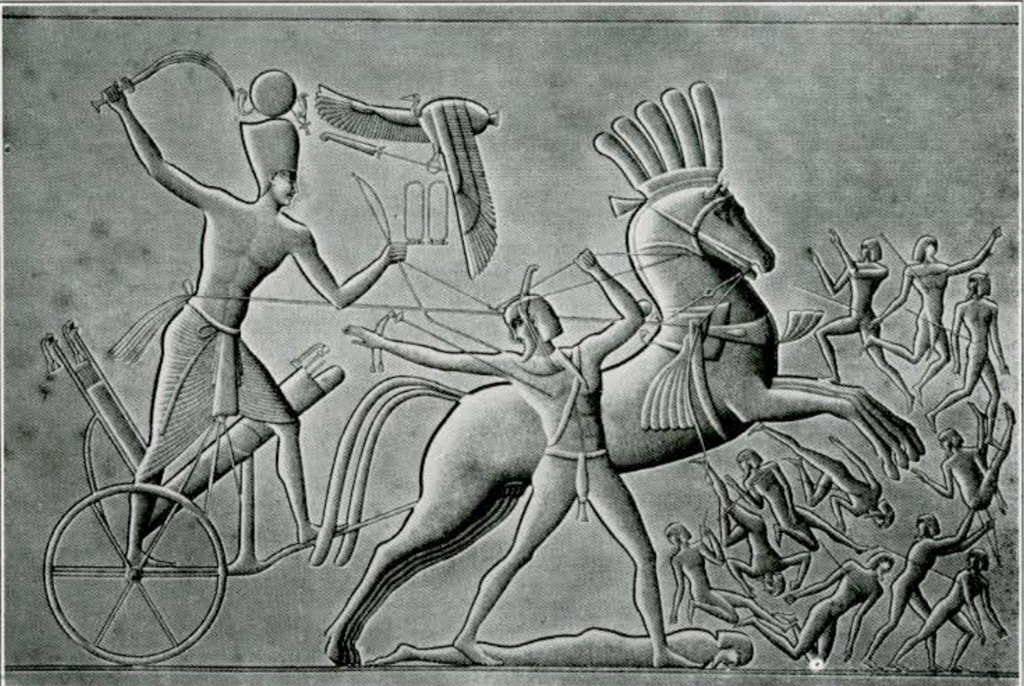

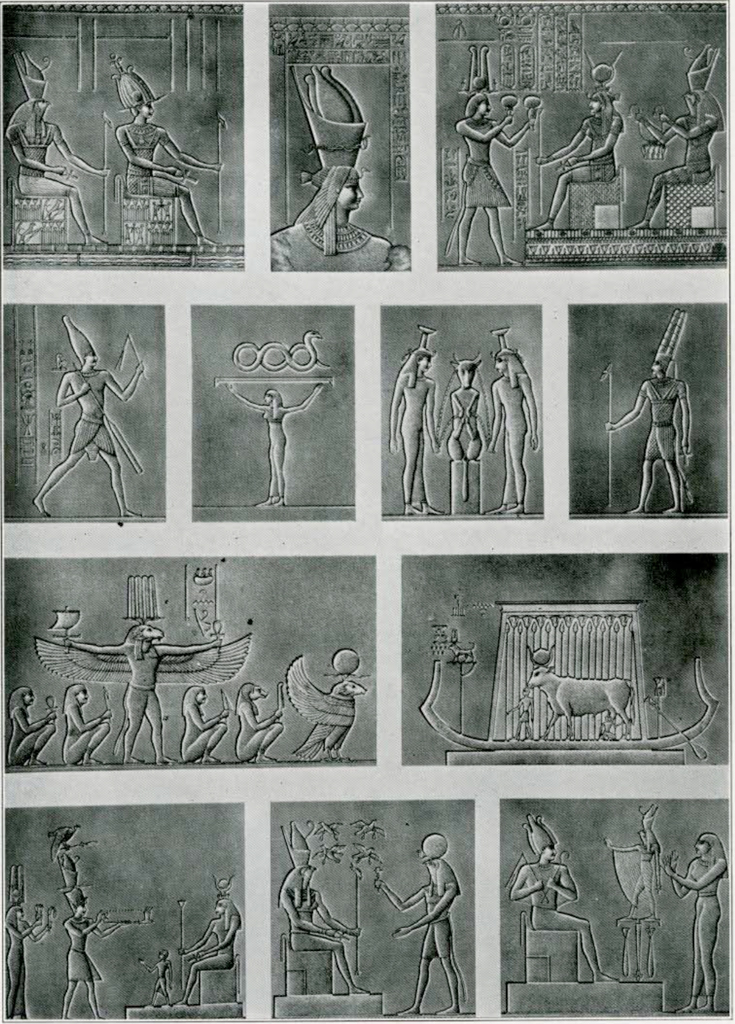

In the Museum’s copy there is a total of 894 separate plates, of which 72 are colored. In addition there are 31 smaller illustrations in the text. The plates measure 21 by 28 inches with the exception of five double size and nineteen triple size folding plates. They are beautifully executed copper plate engravings, representing the best work of a period when engravers were artists and practiced one of the most difficult of the arts. The greatest care was exercised to render these engravings accurate and trustworthy in every detail. The colored plates, executed by hand, are splendid examples of effective coloring. Each plate is in effect a high grade water color from the hand of a skilled artist.

This set of Napoleon’s Egypt is a splendid example of the rare and valuable first edition, complete and perfect in every respect, with wide, untrimmed margins and early, sharp impressions of the plates. It is one of the very few complete sets to be found anywhere, and the only complete set that I have been able to find in Philadelphia. Of four other sets that I have had an opportunity of examining, three were found to lack the full complement of colored plates and did not show the clear, sharp impressions so noticeable in the Museum’s copy. The fourth copy which I examined, while corresponding fairly well with the Museum’s copy in respect to the plates, does not have the text of the first edition, but that of the second. The second edition was published in 1820-1830 in a much inferior style, with poor impressions of the plates and none in colors; while the text was in 26 volumes octavo instead of 9 volumes folio.

I have concluded from my examination of the history of Napoleon’s Egypt that only a few sets of the first edition were issued in a complete state with all the colored plates. As they proceeded with the edition the publishers discontinued coloring at least twenty plates, in order to save time and expense. Since each engraving had to be colored by hand the saving would he very great. The copy that the Museum has been so fortunate as to acquire is one of these earlier copies on which the greatest pains were expended.

DESCRIPTION OF THE WORK

Title.—Description de l’Egypte, ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Egypte pendant l’expédition de ram& française, publie par les ordres de sa majesté l’empereur Napoleon le Grand. Paris, de l’imprimerie impériale 1809-1813 (par ordre du gouvernement Paris, de l’imprimerie royale, 1817-1822). Text 9 volumes, folio, Plates 12 vols. atla folio.

The Text.—The text consists of memoirs and monographs relating to the history, antiquities, geography, natural history, ethnology, etc., of Egypt in both ancient and modern times. It consists of the following volumes:

Antiquités—Descriptions, 2 vols.

Antiquités—Mémoires, 2 vols.

État Moderne, 2 vols., in 3 parts.

Histoire Naturelle, 2 vols.

The Plates.—The plates following the order of the text are disposed as follows:

1. Antiquités, 5 vols.

2. État Moderne, 2 vols.

3. Histoire Naturelle, 3 vols.

4. Cartes topographiques, 1 vol.

5. Preface historique et explication des planches, 1 vol.

To give the reader some idea of the immense mass of material collected by the expedition, and the extent of their explorations we give a brief analysis of these huge volumes.

1. Antiquités.

Vol. I.-Philæ, Syene, Elephantine, Ombos, Silsilis, El Kab, Latopolis, Hermonthis.

Vol. II.—Thebes, including Medinet Habu, El Kurneh, Tombs of the Kings, etc.

Vol. III.—Thebes, continued, including Luxor and Karnak.

Vol. IV.—Kus, Kuft, Dendereh, Abydos, Antæopolis, Lycopolis, Hermopolis Magna, Antinoé, The Heptanomide, etc.

Vol. V.—Memphis and the Pyramids, Babylon, Heliopolis, Athribis, Tanis, Bubastis, The Delta, Alexandria, Busiris, El Faiyum, Sakkareh.

Many of these volumes are rich in manuscripts, inscriptions, figurines, tombs, mummies and minor antiquities.

2. État Moderne.

Vol. I and II.—Costumes, Portraits, Vases, Furniture, Musical Instruments, Coins and Inscriptions, all belonging to the modern period.

3. Histoire Naturelle.

Vol. I.—Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, Fishes.

Vol. II.—Invertebrates.

Vol. II—Second Part—Botany, Mineralogy.

4. Cartes topographiques,

including surveys, plans, etc., from the island of Philp to the Mediterranean.

E.P. WILKINS.