The Northwest Coast of America is inhabited by a number of Indian tribes who possess a culture differing in a remarkable way from that of all the other Indians. While these tribes are thus marked off sharply from the other North American Indians, it is not be be inferred that this difference is due either to Asiatic origins or to Asiatic influence. Statements to the effect that the Haidas or the Tlingit resemble Japanese or other Asiatic peoples in their personal appearance and in their customs should not be taken too seriously. The fact is that the Indians of the Northwest Coast, including the Tlingit, the Haida, the Tsimshian and Kwakiutl, possess a culture peculiar to themselves. They inhabit the mountainous seaboard of Southeastern Alaska and British Columbia and the islands off the coast. In language and in their personal appearance, these tribes differ from each other, but in arts and crafts, customs and beliefs they are so uniform and distinct that they are much more easily recognized as a separate group than any of the other peoples of North America. The most northernly of these peoples are the Tlingit, which include the Chilkat; in the middle area are the Kwakiutl. The two Kwakiutl tribes, the Koskimo and Quatsino, are on the northern end of Vancouver Island. These two tribes have recently been photographed on behalf of the Museum by Mr. B. W. Leeson, who has also collected data relative to their customs. Some of these photographs are here reproduced.

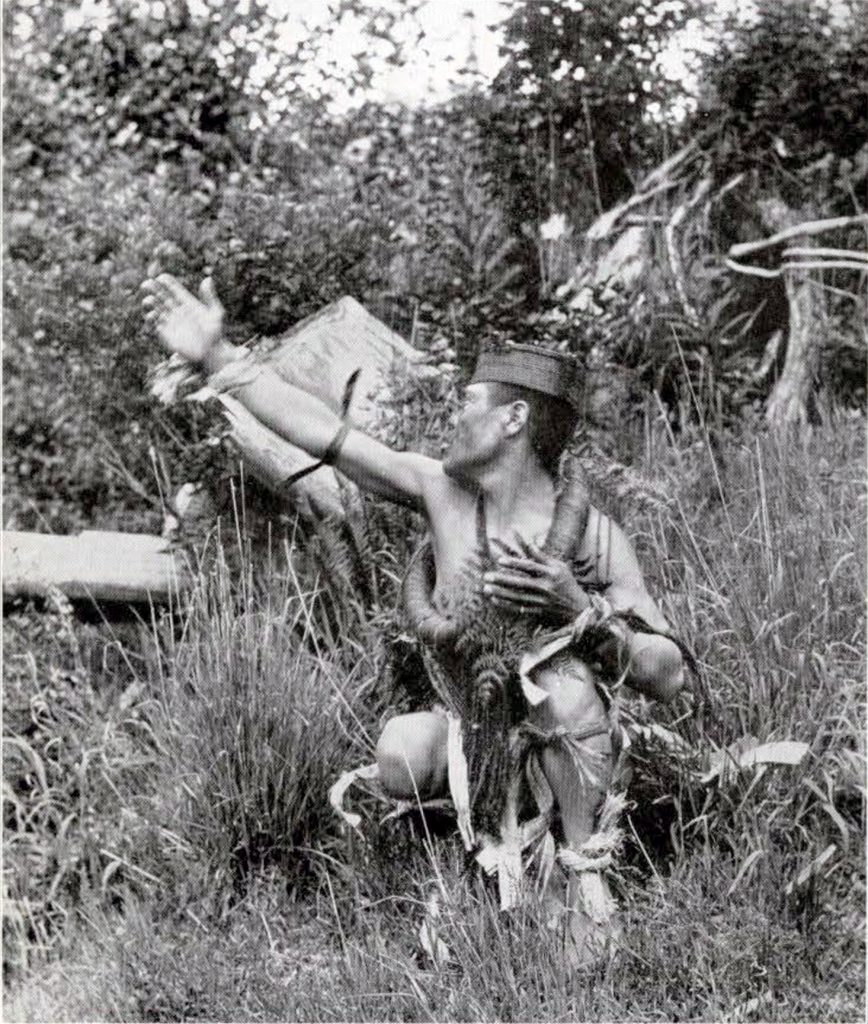

The Kwakiutl have a number of secret societies. The members of these societies perform a very strange ceremony in the winter time. This ceremony is accompanied by dances of a peculiar character. The Hamatsa is a member of one of the secret societies upon whom a guardian spirit has conferred the gift of eating human flesh. During the dances referred to, the Hamatsa, in a state of frenzy induced by the ceremony and its mythical associations, endeavors to seize and devour whomsoever he can lay his hands on, bites pieces out of his enemies and devours the bodies of slaves killed for the purpose. In this condition he also eats human corpses which he takes from the burials in the trees.

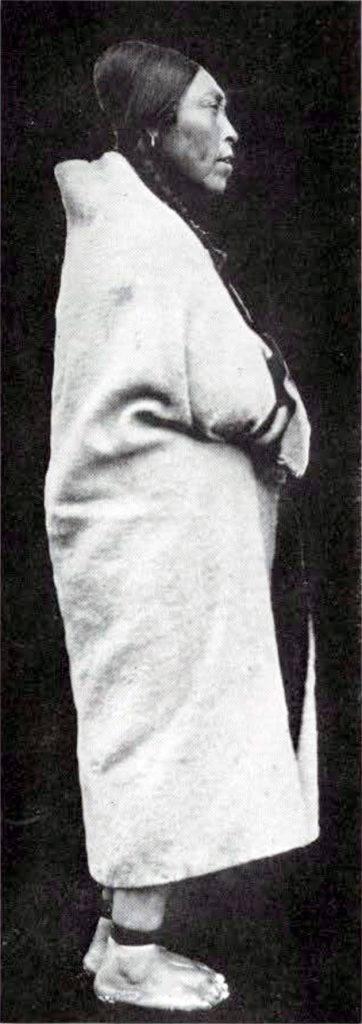

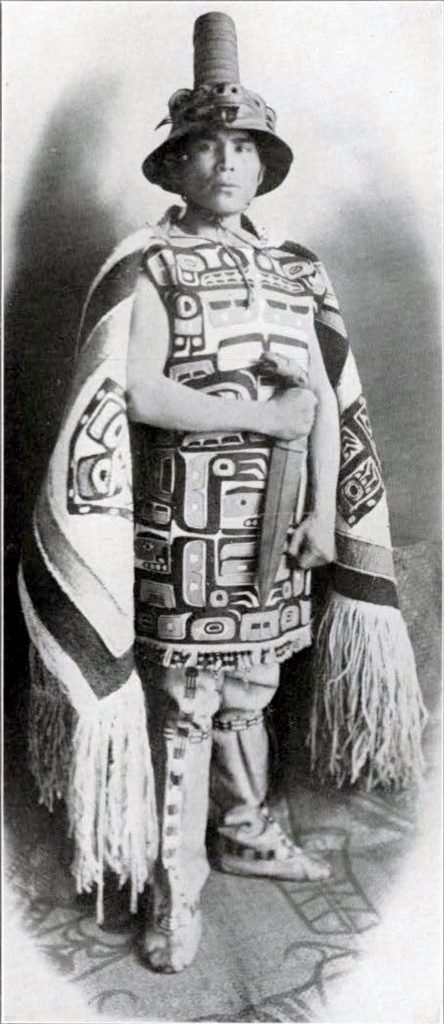

In Fig. 54 the Hamatsa is shown in the position which he assumes in the dance at the time of his greatest excitement, during which he appears to be searching for human flesh to eat.

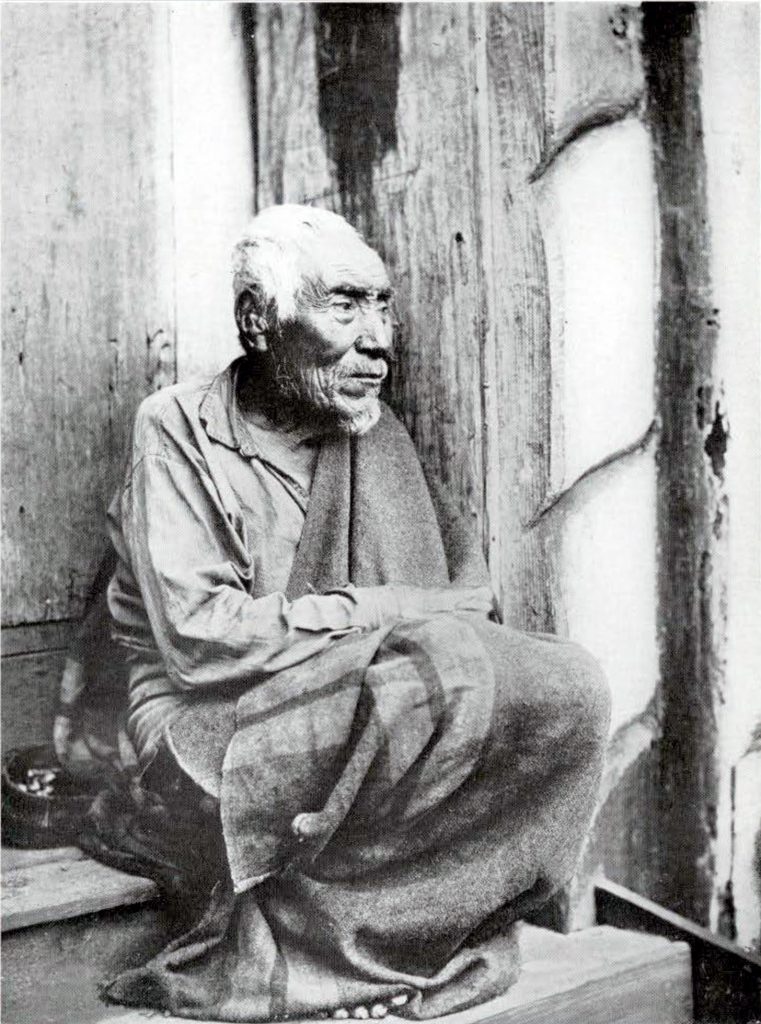

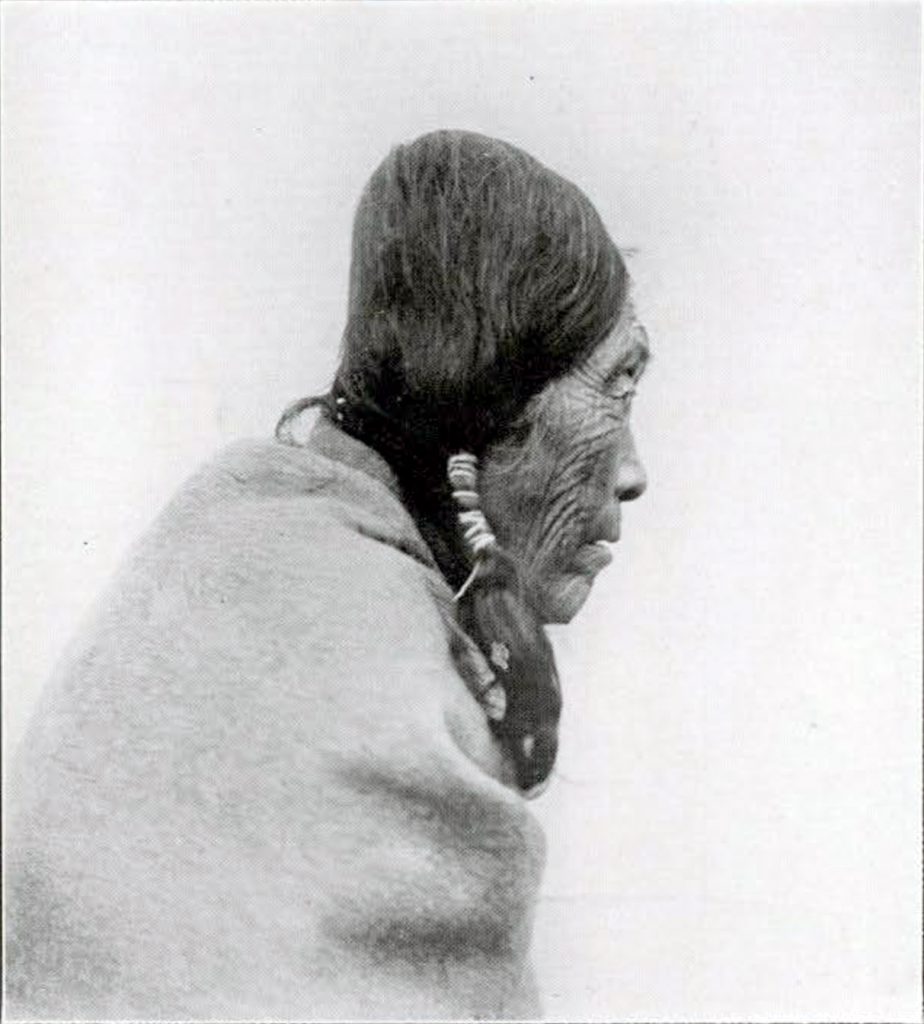

It will be seen from the photographs of the Quatsino that they have the custom of artificially deforming their heads.

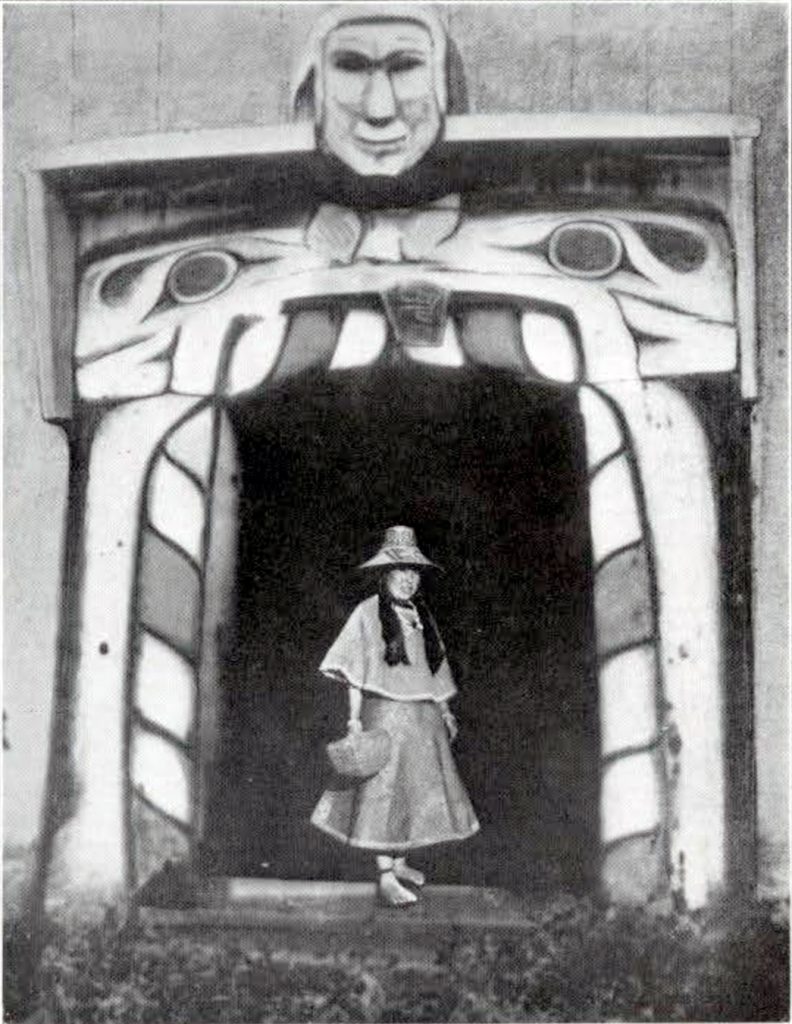

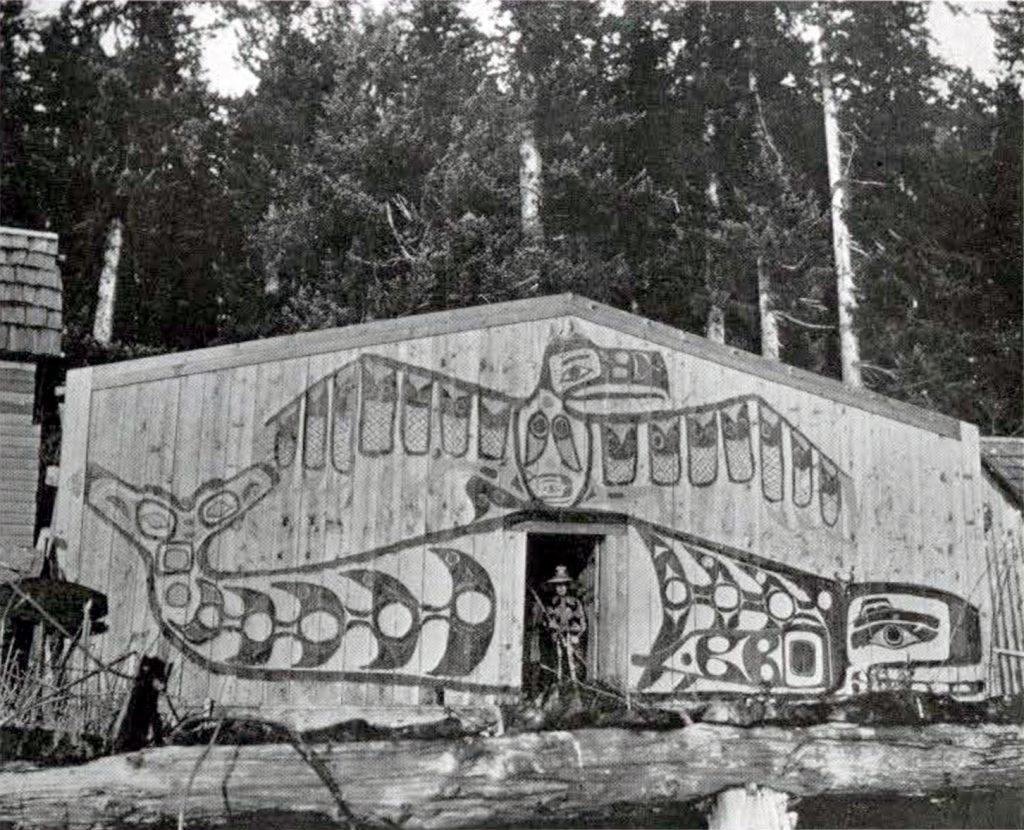

It is characteristic of all the Northwest Coast tribes that they have numerous distinguishing crests which they display upon their houses, and otherwise proclaim. These crests or totems represent animals.

In Fig. 56 is shown the doorway of a Koskimo house. This doorway represents the jaws of a fabulous monster that lived in the water at the mouth of Cache Creek where the Koskimo formerly had their abode. The legend concerning this doorway and its heraldic device is as follows.

Image Number: 12587

In very early times there came on Cache Creek a very large fish known as Stokish. Locating itself where the Indians were accustomed to come for water, this monster gradually decimated the tribe in the following manner. When the people came down for water, the fish, hidden at the bottom of the river, would open its huge mouth and as the water rushed in, the people were sucked in with it. Finally the tribe was reduced to one old man and a young girl. (It is this old man whose face is carved over the door shown in Fig. 56.) The old man and maid were afraid to go to the river for water, knowing that they would be devoured if they did so. At this time there appeared a stranger called Kankokala (who it seems was a kind of supernatural being and a saviour) and the old man and the maid related to him the story of Stokish. Kankokala took off his belt and placing it around the girl, bade her go unafraid to bring water. Thereupon the old man was seized with fear that he would be left alone and protested against the suggestion. Finally the maid went to fetch water by Kankokala’s command and was swallowed up like the rest of her tribe. The old man, now being left alone, set up a doleful lamentation until Kankokala led him by gentle persuasion to the place where his tribe had been devoured by Stokish. Upon their arrival they saw the monster wallowing in the water in great agony. At last, precipitating himself upon the bank he burst open, whereupon the young girl stepped out alive and well. At the same time, the skeletons of the lost tribe came to light and were scattered over the shore. The old man recognized his tribesmen and started to call them by their names. Then he began putting the bones together, taking care that each man and woman should be made up of his and her own parts. Kankokala then sprinkled the bones with water, whereupon they became clothed with flesh and all the tribe came to life, rubbing their eyes as though they had been asleep. The old man, however, had made some mistakes and occasionally gat the parts mixed; that is why to this day some people are born deformed and why you sometimes see a man with one leg shorter than another.

Image Number: 101632

In addition to the pictures of the Kwakiutl there will be found in the following pages some observations on the Tlingit, prepared by Mr. and Mrs. Louis Shotridge.

Mr. Louis Shotridge, an assistant in the Museum, is a full blood Tlingit from Klukwan Village on the Chilkat River in Southeastern Alaska. His father was head chief of the Raven side in Chilkat, and his house was the Whale House. His mother belonged to the chief family of the Eagle side and consequently was a member of the Ka-wa-gan-i-hit-tan (usually pronounced Kagwantan) clan and belonged to the Finned House. Therefore, Louis Shotridge is an Eagle of the Kagwantan clan and his house would be the Finned House. Mrs. Shotridge is a Raven of the Hlukahade clan and belongs to the Mountain House.

Shotridge has made for the Museum a model of a section of his native village of Klukwan and also the drawings which illustrate the articles in the following pages. These articles are written from personal knowledge of Chilkat customs under the influence of which the authors were brought up. Their own education was in accord with Indian practices, and involved the matters of which they write. Whether or not Mr. and Mrs. Shotridge’s statements are always in accord with the observations of others who have written on the subject, it is interesting to record the recollections of members of the tribe who were brought up according to the old traditions.

—EDITOR.

Chilkat Houses

To our tribe and the other tribes inhabiting the coast of Southeastern Alaska and farther down the coast of British Columbia, the “wigwam” or ” tepee ” was not familiar. Substantial dwellings of timber which were the permanent homes of the natives were built in the main villages. A man was proud to be known as a member of his home town where he was born and raised. Aristocracy among our people was far stronger years ago than it is to-day.

Image Number: 141703

During the four seasons of the year it was necessary for the Indians to hunt for the things which each season brought, and for these occasions temporary shelters were necessary, the kind of shelter depending on whether the journeys were taken on land or on water.

Journeys on foot, taken into the far inland during the winter and summer, called for shelters which could be easily carried and which were appropriate for the condition of the weather. During the dry season no shelter was needed for the night. In the rainy season, however, skin tents were used in the open and brush shelters in the woods. Journeys by water were a much easier task, all the requirements for bodily comfort being placed in the canoe. Skin tents were taken along to be erected on shore at night.

The permanent villages consist of provision houses, ordinary dwellings, and family houses. Provision houses are those where foods of all kinds are cured and stored. Ordinary dwellings are homes of the masses. Family houses are those with names, as “Yehl Hit” or Raven House, “Hoots Hit” or Grizzly Bear House, owned by families of the classes. The occupants of a family house are the head man or “Master of the House” and his family, relatives, and sometimes distant relations. In this house also are held feasts, councils, and gatherings for all public interests. The chief’s family house, although it may not be very elaborately finished, is looked to with much regard. In it are kept the old relics, such as ceremonial costumes, helmets, batons, carved and painted screens and posts, all original things that had been in the possession of the chief’s ancestors. In it also are held the more important public meetings.

Image Number: 12581

In order to fully appreciate the importance of a “family house,” it will be necessary to tell how society is organized among our people.

The Tlingit are separated socially into two sides. One side is known as the Raven, the other as the Eagle. This division is based on ties of blood, for the members of one side are said to be kindred; therefore the Raven man marries the Eagle woman and the Eagle man marries the Raven woman, while the children always belong to the mother’s ” side.” In times of war, or when there is an uprising of one side against the other side, the mother takes the children to the house of her uncles and brothers or to her side, while her husband would be on the opposite side and stay apart until trouble ceased.

Each side is subdivided into clans, the members of which are more closely related to one another than to the whole of one side. Clan with us means a collection of families under the same totem. Totem is a figure of a bird, beast or the like used to distinguish to which side a clan belongs, whether the Eagle or the Raven, for though the same totem may he used by different clans on the same side, the same totem is never used by clans on opposite sides. Finally, the clans are subdivided into families or house groups, the members of which may own one or several houses, though very few own more than one.

Image Number: 12580

As there are classes among all nations, so are there classes among our people. Although the clans are said to be higher and lower than one another, yet with the families the grade is more emphasized. The different classes were and are: families of the nobility, who were few in number and to-day are still less; families of the high caste, among whom grades of a certain kind are recognized; artists, who are looked to by all classes with a certain courtesy and who may come from any class; families who have worked themselves up with wealth but can not buy themselves into the high caste so as to be their equals; then the common people.

To prevent troubles and wars, the Indians were careful to marry their equals, for if they made unequal marriages, as was sometimes the case, there would be a feeling on one side or the other caused by one being lower or higher in birth than the other and a little disagreement would spring up, something of which one was sensitive, affecting both families, and if very serious, both clans, causing bloodshed and sometimes war. Of course these things happened very seldom; to-day such troubles don’t go beyond families.

The brother of the chief or his sister’s son is his lawful successor. If there are several brothers or nephews, the council of the side composed of the masters of the houses decides which shall be chief.

Some houses have been entirely lost through want of a proper head. To prevent such calamities the more conservative families have given their sons special training in order to preserve the name of the house and of the family.

Image Number: 12578

There is no ceremony connected with building the ordinary houses and the houses where provisions are prepared and kept. The erection of a family house, being a monument to the family, is, however,- a formal occasion. Distinguished persons of the opposite side are called together by the chief and his relatives, and to them is assigned the supervision of the work. Posts, beams, planks and other parts are allotted to a number of men. These massive structures were formerly built with the stone and wooden implements used by the Indians.

The carvings and paintings were usually done by famous artists. I (Mrs. Shotridge is writing) have often heard my father say with pride that his house totems were painted by Shkecleka. Shkecleka was of the nobility of the Raven side and besides being the most famous chief of the Ravens was a clever artist as well. These house totems are very old, having been erected by my father’s ancestors. They were repainted by Shkecleka when my father was a boy. I can remember the rebuilding of the house, or rather some incidents connected with it, although I was then but a small child. What impressed me most was the mountain of steps at the en trance. I was so tired going up these steps that I begged to be carried in the ceremony attending the opening of the house. A long line of women dancers formed around the room, and I cried to be allowed to dance with my aunt. They finally gave permission in spite of the fact that I was of the Raven side and the dancers were of my father’s side, the Eagle. This was but one of the many dances which were performed during the feast which attends the opening of a family house and lasts a week. There were a certain number of them, each being danced in its order.

Image Number: 12574

In these houses with the opening in the roof for smoke and air kept open day and night the year round, it was impossible to have impure air, and diseases common among the white men were almost unknown to the Indian. Very few of these houses are to be seen to-day as they are being replaced by modern dwellings.

The analysis on page 100 shows the social organization of the Tlingit.

The Eagle side in Chilkat was divided into three clans, and each was named through some incident that occurred to it during the traditional migration from the south to Chilkat. It is said that at one time the three clans were classed under one head, namely, Shun-gu-kay-de. At one camping place the head family lost their winter camping house by fire. Further on nearly half of the moving party lost their course in the fog and strayed into the inside passage, which caused delay in reaching their destination. Some of the party got discouraged, and contented themselves at some favored sand beach until some one grew with courage enough to go on, and these finally reached their destination. Since then the first group is called Ka-wa-gan-i-hit-tan, meaning the people of the house that burned; the second is called Dak-da-wo-si-dak-i-na, meaning the people that strayed into the inside passage; and the third is called Dak-cla-wo-ya-da, meaning the people of the inside sand beach.

The Raven side divided ‘and received their individual clan names in a similar way.

Finally the clans were subdivided into house groups, the members of which might occupy one or more houses.

According to the strict rules of the tribe, one must marry his equal in blood from the opposite side, that is to say the Eagle man, of the Grizzly Bear, Killer-Whale or the Finned houses, may choose his wife from either the ‘Whale or the Raven house of the opposite or the Raven side; but their children always belong to eht mother’s or the Raven side. In this case, if the son should take his office on his or the Raven side, while the father is yet holding his on the opposite or the Eagle side, they (father and son) would have to be against each other if some trouble should rise between the two sides.

Each one of the house groups of both sides always has a head man, who at times of councils acts as the representative of his own house group. For instance, if the chief of the Eagle side should call an important meeting or council, the head man of the Young Tree house would act as a voice for his own group, of which he is also a captain at times of war.

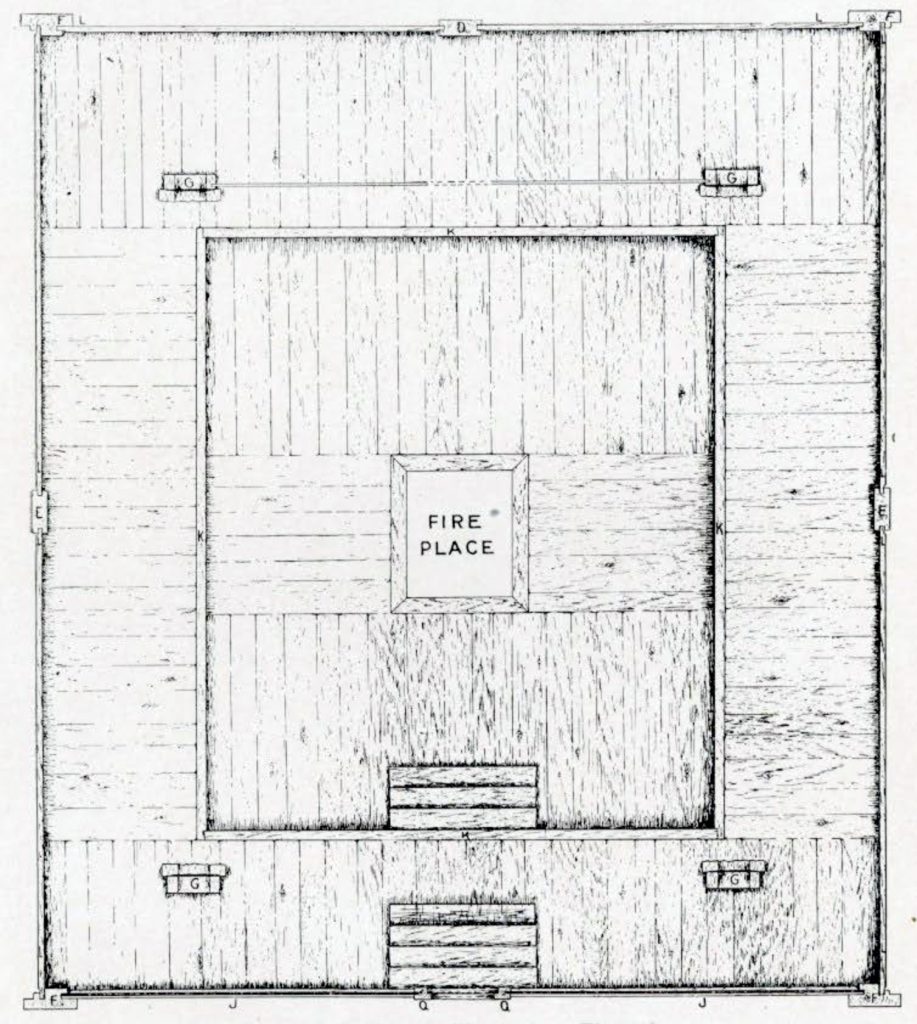

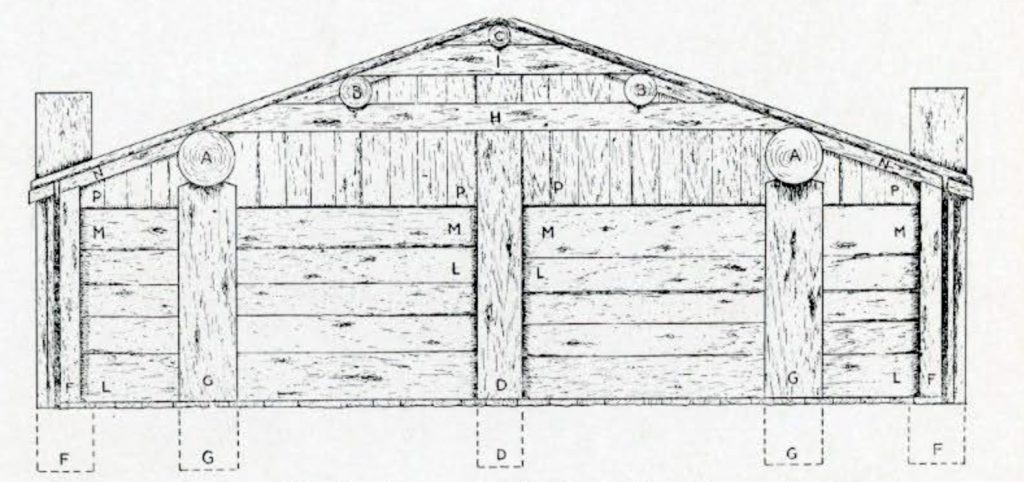

Chilkat Dwelling House

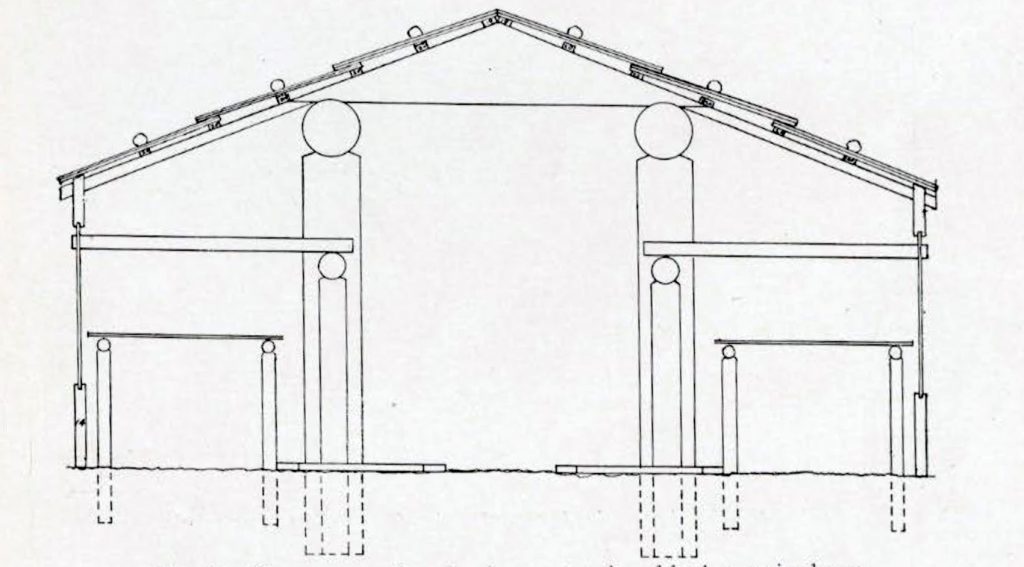

In olden times, when Chilkat people were yet large in number, the dwelling houses of the chiefs, which were frequently opened for public meetings, such as might be councils or festivals, were built much larger than those of recent years. These old time houses were erected entirely without nails or spikes, but all the different parts were made so as to support one another.

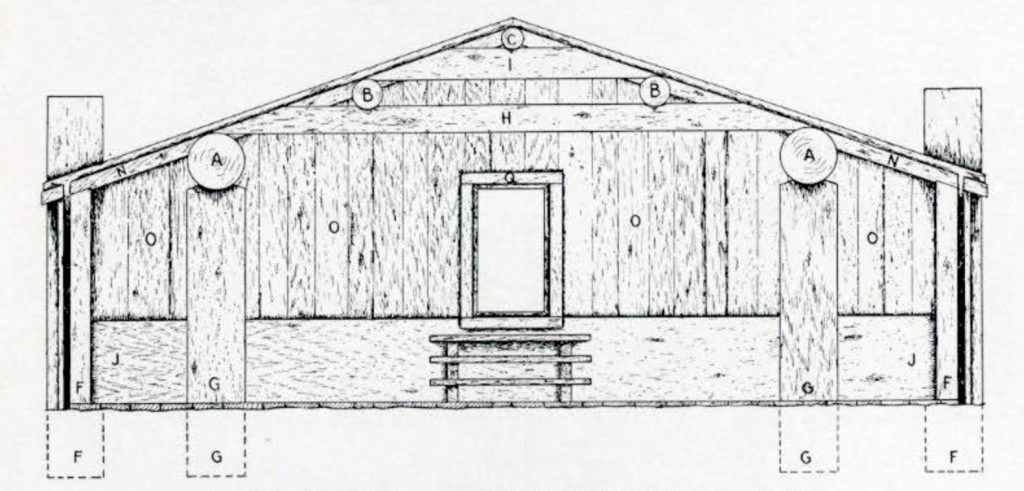

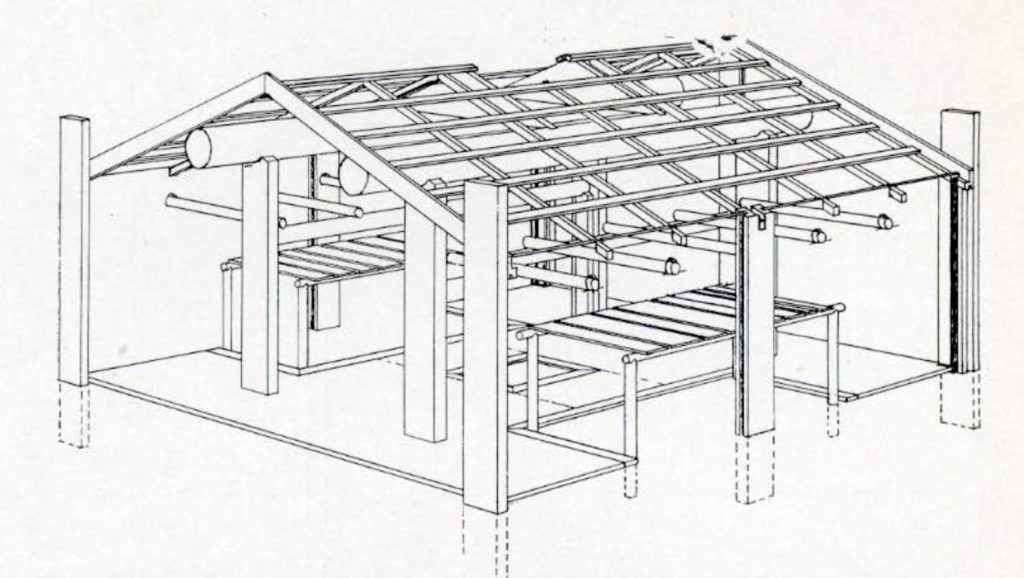

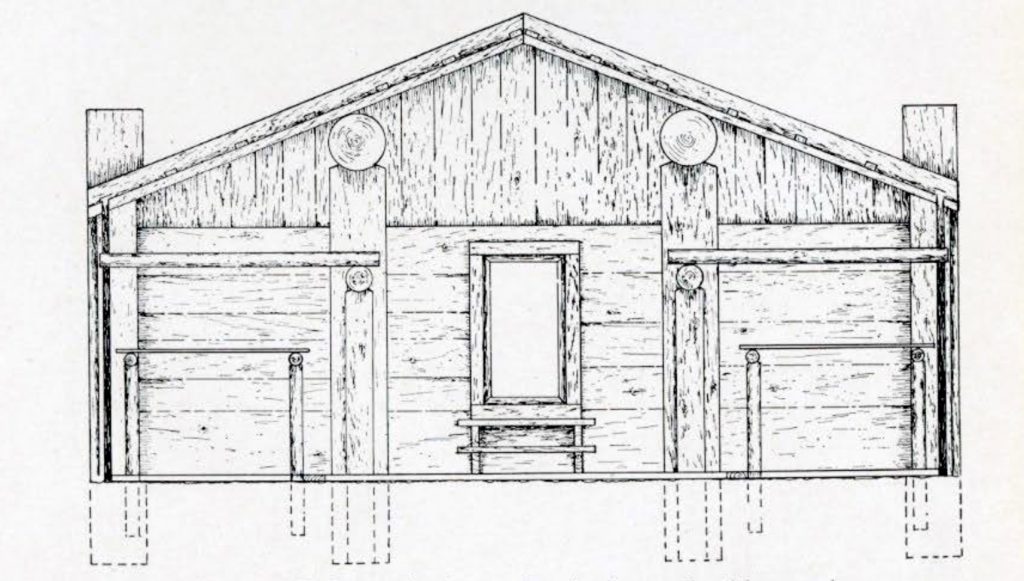

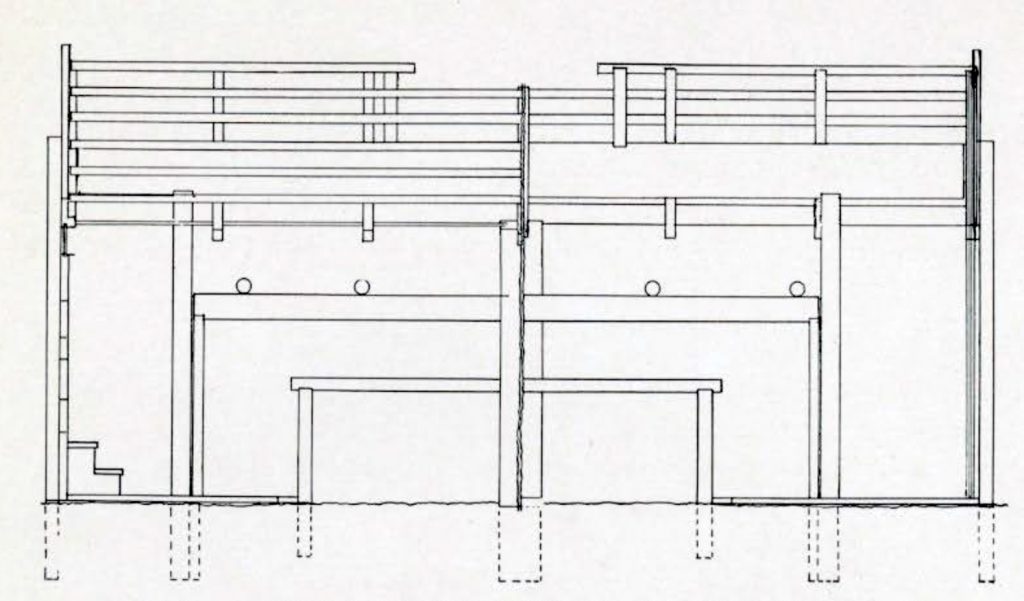

Image Number: 102447, 12584

Image Number: 102405, 12583

Spruce being the only tough and straight large tree that grows near Chilkat, was used for nearly all the timber of the framework of a dwelling house, while hemlock, although it is not as tough as the spruce, but splits better, was made into boards and planks. Instead of hemlock for finishing work of both interior and exterior in some of the houses of well-to-do people, red cedar was used, which was not a native wood of that section of the territory, but was transported by canoes mostly from the Queen Charlotte Islands.

In those days measurements were made by the thickness of the fingers, the span of the hand and the joints of the arms.

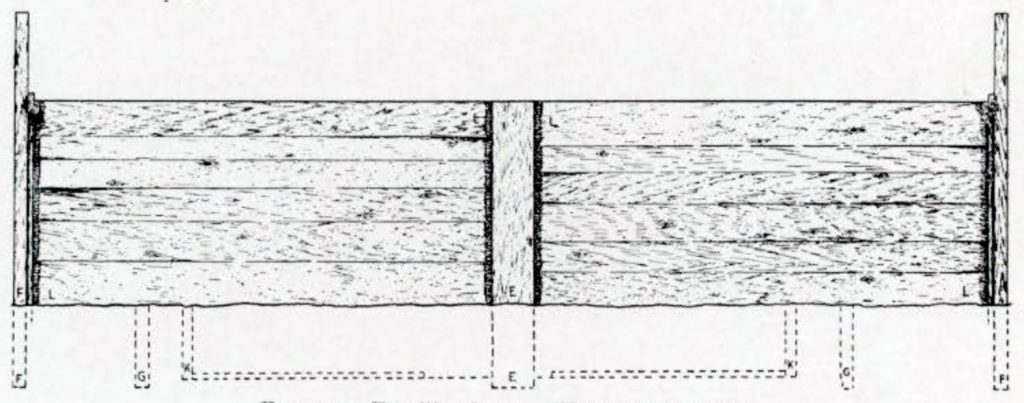

The methods of erecting a permanent dwelling house which are illustrated by the drawings are those commonly known among the Chilkats. In the house selected for illustration the main roof beams are 44½ feet long and 2 feet in diameter. All the other parts are in proportion.

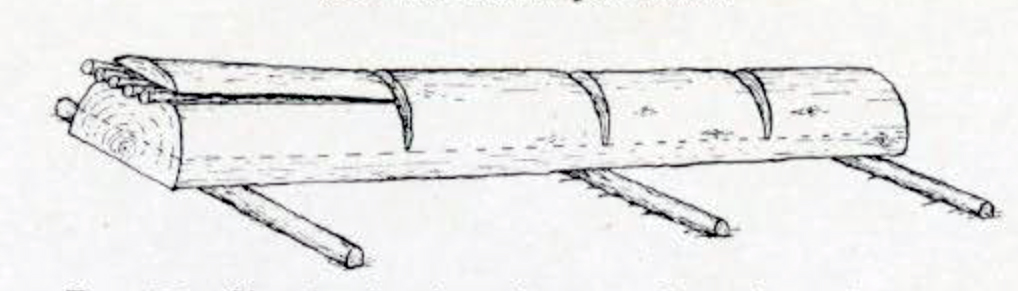

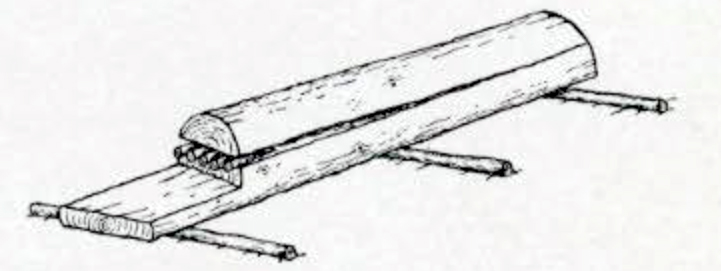

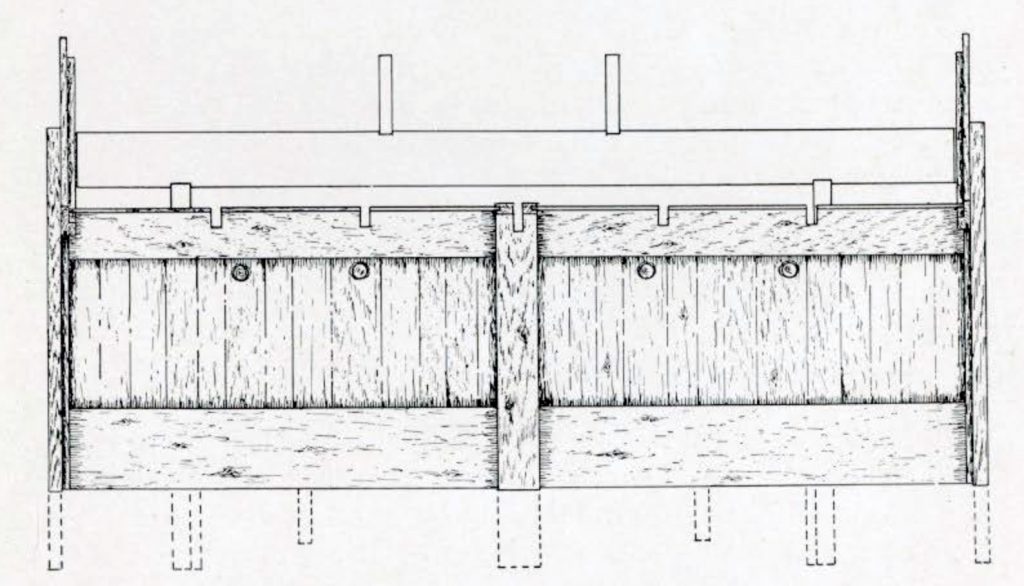

All the materials for these houses were made from selected trees which had to be straight and free from knots. The trees to form the great roof beams were first felled, cut to the proper length and cleared of the bark; then they were reduced to uniform diameters by chipping with the stone adze. The upper roof beams were made in the same way, but of smaller trees. The ridge beam likewise was of a still smaller tree and might not be more than twelve inches in diameter. The corner posts and the side posts were dressed to the proper size and form by reducing the logs cut to the proper lengths by splitting with wedges and afterwards dressing with the adze. By means of the adze the grooves were cut out from the edges of these posts to uniform depth and thickness to take the ends of the planks forming the walls. The great planks that formed the walls were split from logs of straight grained hemlock to uniform thickness by means of wedges. The covering of the roof was composed of heavy split shingles.

Image Number: 12585

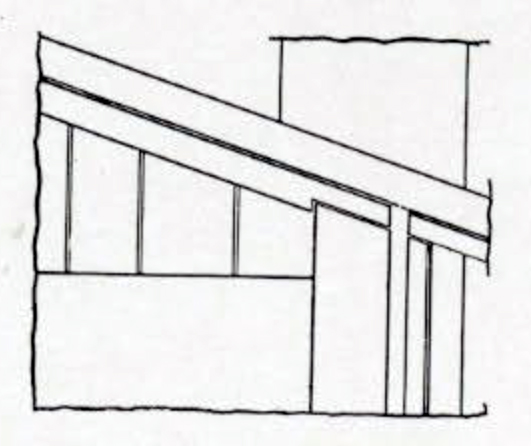

While the planks on the sides of the houses and rear were placed horizontally, those on the front were placed vertically, their lower ends being fitted into the grooves in a heavy base plank lying horizontally like a sill between the two front corner posts.

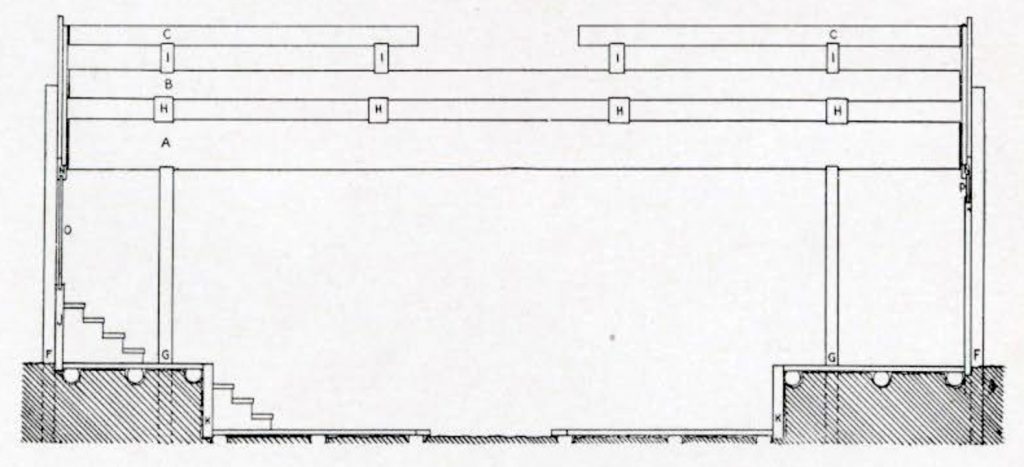

In the inside arrangement of the houses were two floor levels, the middle area being depressed about two feet, leaving the upper area like a raised embankment. Both of these areas were covered with plank floors, which, after being laid in place, were smoothed off by means of the stone adze. In the middle or lower area, an open pit without floor was left for the fireplace. On the outer and upper floor area were provided the sleeping arrangements. Since the inner floor level was below the outer ground level this part of the house was free from draughts. The threshold of the door was also raised and reached by a flight of steps from the outside as well as from the inside. This was to clear the average snow level in winter. In the middle of the roof, directly over the fireplace, was the smoke hole. Sometimes this was protected on both sides or on one side by wind-breaks, but this device was not altogether approved since it shut out a good deal of the light.

Four great pillars were set up in the interior at equal distances from the corners to support the heavy roof trees. These were carved with the heraldic devices of the family. Between the two rear posts so erected was usually placed a great carved screen with an opening in the middle; beyond this screen was the chief’s private apartment.

The space on the upper floor level or embankment was usually divided according to the number of people who were to live in the house. Those preferring privacy were given the privilege of enclosing their sleeping places by means of screens. Some of these enclosed sleeping apartments were built with an upper story. Noted warriors of the family living in the house were permitted to have the titles of their war parties carved on the front screen of their sleeping apartments.

Image Numer: 12577

Image Number: 101648

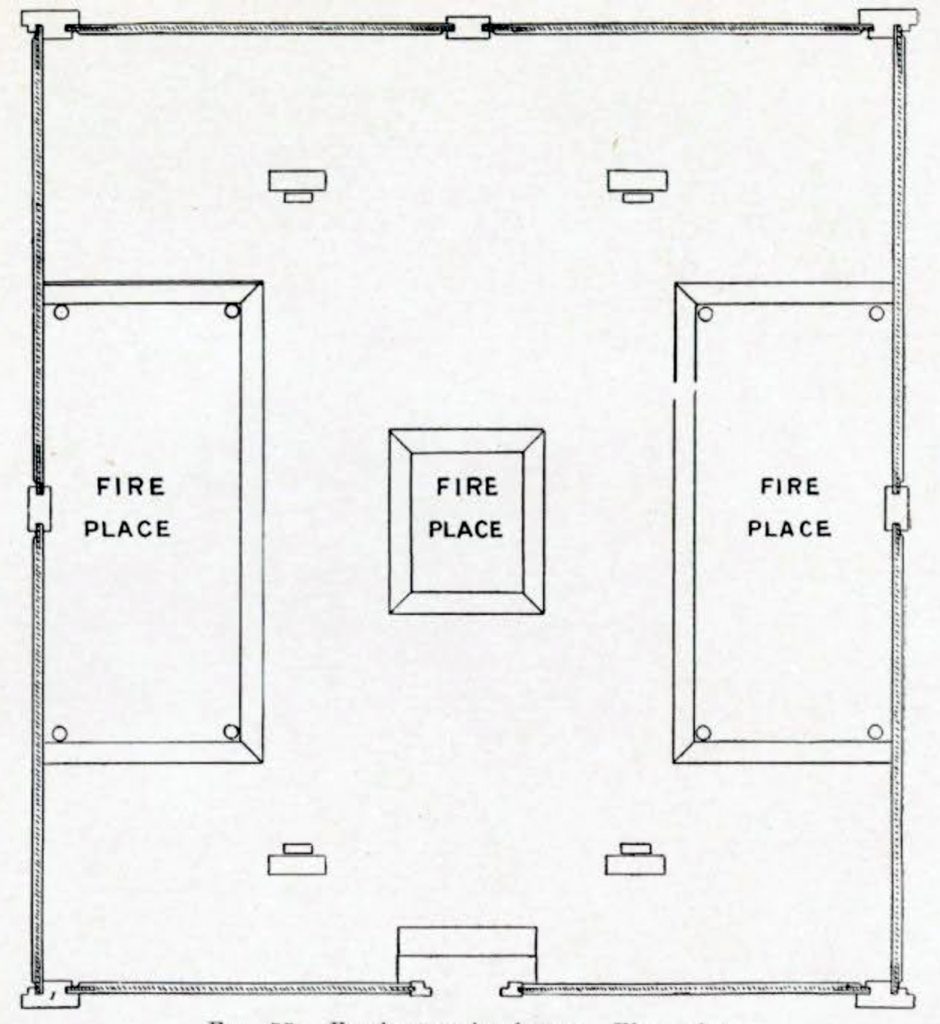

Smoke or Food Preparing House

This was usually constructed near the water’s edge for convenience. It is similar in construction to that of the dwelling house with the exception of the framework of the roof, which consists of rafters with horizontal poles supporting the shingles.

The interior of the smoke house differs from that of the dwelling house. The middle floor area is not depressed. There are three fireplaces, one in the middle and one at either side. Over each of the fireplaces is erected a smoke spreader. These consist of boards resting on poles which, in their turn, are supported on posts.

In the old days it was usual to secure the shingles of the roof on all classes of houses by means of horizontal poles weighted down by heavy stones. Sometimes, however, instead of being weighted with stones, horizontal poles were lashed by means of spruce withes passing through holes burned in the shingles for this purpose.

House Posts and Screens and their Heraldry

With the introduction of steel and iron implements among the tribes of the Northwest Coast totem poles became numerous. Numbers of them could be seen in front of houses in the more southern villages. But before the modern tools, it is said, totem poles were rare, not only on account of the difficulty in the making—as stone and wood were used for tools—but the desire to keep them strictly distinctive was a reason for their scarcity.

One often hears it said by the older people that originally totem poles were used inside of the houses only, to support the huge roof beams. The carvings and paintings on them were usually those of the family crests. These posts were regarded with respect very much as a flag is by a nation. Even when the Chilkats had acquired modern tools with which to make totem poles they did not fill their villages with tall poles like some other tribes, chiefly because they wanted to keep to the original idea.

The figures seen on a totem pole are the principal subjects taken from tradition treating of the family’s history. These traditions may treat of the family’s rise to prominence or of the heroic exploit of one of its members. From such subjects the crests are derived.

In some houses, in the rear between the two carved posts, a screen is fitted, forming a kind of partition which is always carved and painted. Behind this screen is the chief’s sleeping place.

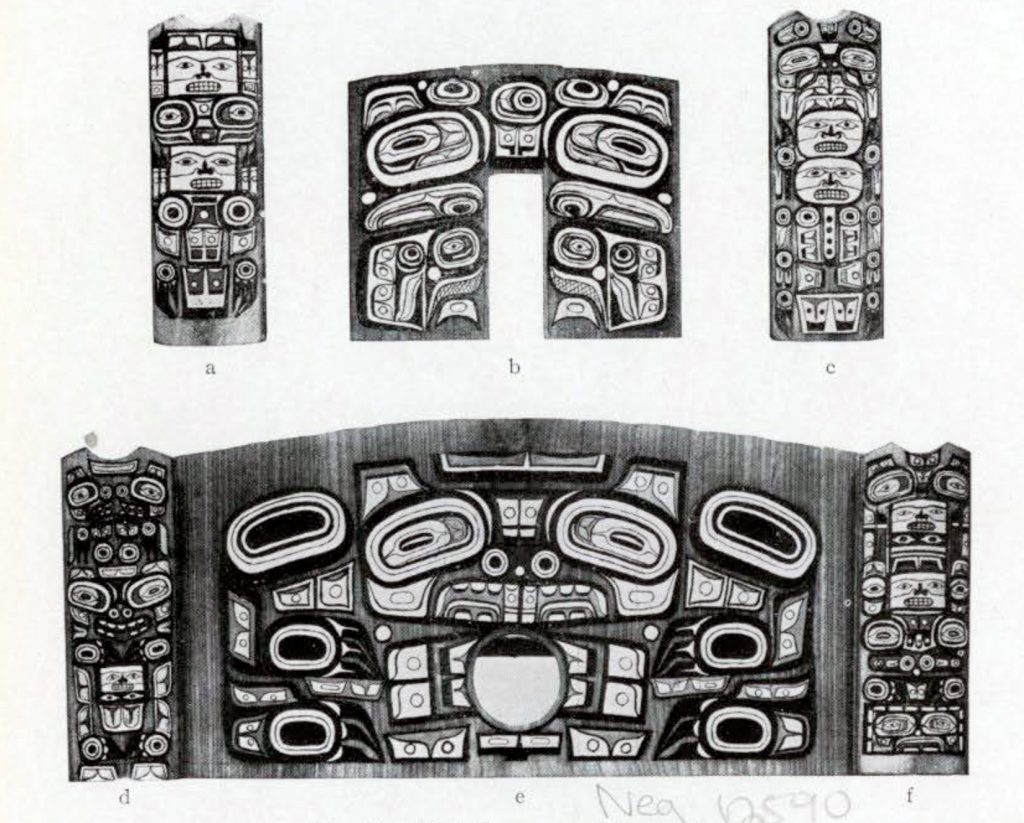

The smaller screens along the side walls are seldom decorated, as this is done only when a chief’s nephew or brother has distinguished himself in war. One of these small screens is shown in Fig. 83b. The emblem is “Killer Whale.” It is said that this emblem was adopted by the Kagwantans during the war times, when they were at war with the southern tribes who live on the shores of the main ocean where these deep-sea fishes are common. The Kagwantans (Ka-wa-gan-i-hit-tan) are a clan of the Tlingit tribe and are noted for their bravery and audacity, besides being known as the strongest clan in southeastern Alaska.

The grizzly bear is their highest crest. The origin of it comes from the girl taken by a bear for wife. The story is often told in the following manner.

There once lived a chief who had many sons and an only daughter. The girl was beautiful, just growing into womanhood, and was much sought after by young men from many villages, but all were refused for some reason. The boys were great hunters and brought rich furs to be made in garments and robes for their sister.

One day the princess and her friends formed a little party and went berry-picking. After gathering all they wanted they started for home. After they had gone a short distance, the princess stepped in a bear’s track and slipped, remarking at the same time something uncomplimentary about bears, which was considered wrong, for it was believed that the spirit of an animal could hear and would often treat the offender according to the offense. The girls stopped and helped the princess up. A few steps farther the pack-strap of her basket broke; the girls waited until she fastened it, but after going a short distance the strap broke again; this time she told her companions to keep on going, she would catch up with them in a little while. It was dusk already. The girls went on and left her to fix her strap. While she was working on it she heard footsteps behind her. With a frightened look she turned and saw a handsome young man standing close by. He offered her assistance; she accepted; he picked up the basket and told her to follow him, which she did. Late in the evening they reached the village, but it was not the girl’s home. She immediately thought that this young man was the prince she was waiting for and that he had come to take her to wife. Feeling that she did right in following him she decided not to speak to him just then. He finally said, This is my father’s village, his house is in the middle of it, there I am taking you.” When they came to the entrance of the house he said, ” Father, I am bringing home a wife.” The chief arose and welcomed them, called together his people and gave a feast in honor of the couple.

For awhile the princess lived contentedly with her husband’s people, but later she began to see many strange things. Men came in from fishing with wet coats, and as they shook them in front of the fire to dry them, the drops of water would blaze tip in the most extraordinary way. All this was puzzling to her. She longed to find out what it all meant, so she asked her husband if she could go with him on his next trip to the fishing camp. At first he would not let her go, as she was not used to doing rough work. She insisted and he finally gave his consent; so she went along.

At the camp, while the men fished the women got wood for the fires. The girl gathered the driest wood she could find. The other women, she noticed, were gathering water-soaked logs and sticks. After making a large pile she made her fire in the way she knew her people made it. It was burning nicely until her husband came from fishing. As he shook his big wet coat by the fire the drops of water put it right out. The girl was ashamed of not knowing how to do her part, and was even more so when she saw how the other women’s fires blazed up when their husbands shook their coats by it. Her humiliation was more than she could bear. She knew now that there was some mystery about the people among whom she was thrown.

The day’s fishing done, all went home. That night the girl thought of all that had happened and had a troubled sleep. In the middle of the night she awoke with a shock. What monster is this in the place of her husband? a large grizzly bear! The monster felt her start and awoke with a low ” ah” and with that he turned into the form of the man she knew as her husband.

It all came to her now: she was among the bear people; the lights and blazing up of wet logs were phosphorus; this bear had taken her for revenge because she had abused the bears when she slipped in the tracks. She wanted to run away, but she could not do it. She had been there nearly three years and had two sons. A longing for home came over her and she felt miserable. But while in this mood she felt her mind change and was her former self again. The bear had power over her.

In the meantime her parents and brothers gave up all hope of finding her and mourned for her death according to the custom among the Tlingits.

It was early in the spring of the year that their sister discovered her situation. It happened at the same time that the brothers went hunting in a direction they had never taken since their sister’s disappearance. They knew that there would be plenty to kill there as the place had not been hunted. Their hunting led them towards the place where their sister lived with the bear people.

In the bears’ dens–which looked like houses to the girl—there was a general preparation of going away to the summer camps,-spring coming on, the bears were getting ready to come out.

One morning the girl’s husband all of a sudden was startled, straining his ears as if he heard something at a distance; then he looked confused then he began taking his spears down from the wall and sharpening them (it looked so to the girl, but the bear was grinding his teeth), for well did he know that hunters were near.

All at once they heard a dog barking outside; the bear jumped up and rushed out; he caught the dog and threw it in; the girl recognized it as her brothers’ dog. She was quick to think; called to her husband and said, ” Do not fight, they are your brothers-in-law.” The bear drew back and waited for the hunters to come up, then went forward and gave up his life, for he knew he was in the wrong by taking away the princess.

After a few minutes the girl heard voices; she came out and saw the bear lying on the snow with arrows in its side and men, who were her brothers, just about to cut it. She spoke and said, ” Do not take the bear, he was your brother-in-law.” They looked at her, as may be imagined, with surprise, sorrow, and gladness—surprised to see her in that place; sorry for the life she went through, and glad to find her. In a few words she told her strange life. She had never noticed her appearance until after speaking to her brothers: her dress was ragged and worn up to her knees, a pitiful sight to see. The men buried the bear, and took their sister home, leaving her two sons, for they were cubs with half human faces, one of whom was “Kats.” This name is still used.

Through this woman the Kagwantans claim the grizzly hear as their crest, emblem of strength and high rank. It is always the principal figure on their totems.

In Fig. 83 are shown the screens and house posts belonging to one of the family houses of the Chief Family of the Kagwantans, whose crests and emblems or totems are elaborately displayed on these screens and house posts in carving and painting. On the large screen e is displayed the Grizzly Bear. On the smaller screen b is displayed the Killer Whale, whose presence is explained on page 94. On the house post a is seen Lgayak, on the second house post c is displayed the Two-headed Bear, on the third house post d is displayed the Wolf and Pups, and on the fourth house post f is displayed the Bear and Cubs.

The emblems on the houseposts are derived from the mythical narrative, Lgayak, preserved in the mythology of the Kagwantans. Lgayak is the name of the younger of seven brothers, whose deeds are related in this myth. He was the hero of the story and through his prowess he and his brothers were able to conquer the enemies of mankind. They destroyed the beings that were to have been the foes of men. One of the strongest of all the monsters that

they fought was the Double-headed Bear, whose image is carved on one of the posts.

LOUIS AND FLORENCE SHOTRIDGE.

Image Number: 12590

Image Number: 12562