The process of making glass was invented, according to Pliny, in the following manner. ” That part of Syria which borders on Judea., and is called Phoenicia, has at the foot of Mt. Cannel a swamp named Cendevia. Here rises the river Belus which, after a course of five miles, empties into the sea near the colony, Ptolemais. This river runs but slowly and unwholesome is its water, though used in many sacred ceremonies. Its bed is muddy and deep. . . . At ebb tide there is left here a very clear and bright sand which extends as far as 300 paces. Now there arrived at this place one time certain merchants in a ship laden with nitre, and being minded to cook their dinner on the shore and finding no stones close at hand they made shift to support their kettle with blocks of saltpetre from their ship. After the fire was made they noticed, mixed with the sand beneath the pot, a very bright and clear stream, and this was the beginning of glass. “By us of a scientific generation this story may be readily dismissed as a fabrication devised for the purpose of explaining the facts of glass manufacture, but by the ancients it was believed and the Phoenicians were accredited by them with the invention of glass. At the hands of modern archaeologists, the Phoenicians are being stripped of much of their former prestige and among the losses they have sustained must be reckoned that of the credit of this invention, for it has now been shown that it was Egyptians who first made glass, and that the invention dates from so remote a period as the fourth millennium B.C., when glazed beads and other glazed objects were first manufactured.

Museum Object Number: MS5254

For many years the east coast of the Mediterranean knew glass only as a costly import. The word occurs but once in the Old Testament, in Job 28: 17: ” The gold and the glass cannot equal it, and the exchange of it shall not be for jewels of fine gold,” a passage which implies, of course, its great value. Not long after the time of Job, glass factories had been established at Sidon the products of which were much prized by the Romans. To this manufacture the invention of glass-blowing in the early imperial period gave new impetus. Not only in Phoenicia, but also in Syria and Judaea the industry assumed large proportions. Jewish glass, vitrum Judaicum, was famous even in the Middle Ages; indeed, Harriet Martineau in the last century saw glass-makers at work at Hebron, and their products selling in the Palestine markets.

But it was in the Roman period that the industry was at its height. The collector of Roman glass, therefore, finds in the eastern littoral of the Mediterranean nearly every category of glass known to the ancients. Many shapes and types correspond entirely to those made in other Roman provinces, in France or the Rhine valley; others are peculiar to the east.

The Museum has acquired from Jerusalem two collections of glass, comprising 392 pieces and consisting mostly of vases. There are also a number of glass pendants, bracelets, intaglios, and necklaces. Some of the necklaces are of glass and some of carnelian, amethyst, rock-crystal, and agate. All were found in Palestine and Syria, and were taken from tombs mostly in the district between Jerusalem and Aleppo. The sites on which the tombs were found are in many instances familiar on account of their biblical associations: Hebron, Damascus, Nazareth, Moab, and Sharon.

Roman custom ordained that the dead should be equipped in their graves with all that had been of use in life. Vases filled with milk and honey and wine were set beside them to satisfy their hunger during the long journey on which they had embarked. The child, moreover, had his toys.; the woman her vases for toilet. In the imperial Roman period, in the eastern Mediterranean, vases of glass largely superseded vases of clay for these purposes. And naturally, for their cost was slight; in Nero’s time a small-sized copper coin would buy a goblet of glass.

Museum Object Numbers: MS5101 / MS5099 / MS5100

Image Number: 3581

Museum Object Number: MS5119

Image Number: 7746

These ordinary specimens, bought for a penny in antiquity, sell now for fabulous prices if they chance to have acquired from their long contact with the soil a brilliantly iridescent surface. Such iridescence, unknown to the ancients, unsurpassed by the beauties of modern glass, is due to a partial disintegration of the surface, which, after a sufficiently long lapse of time, may prove disastrous to the preservation of the specimen. Many vases with brilliant opalescent hues are included in the Museum’s purchase, and will prove a source of delight to every lover of color.

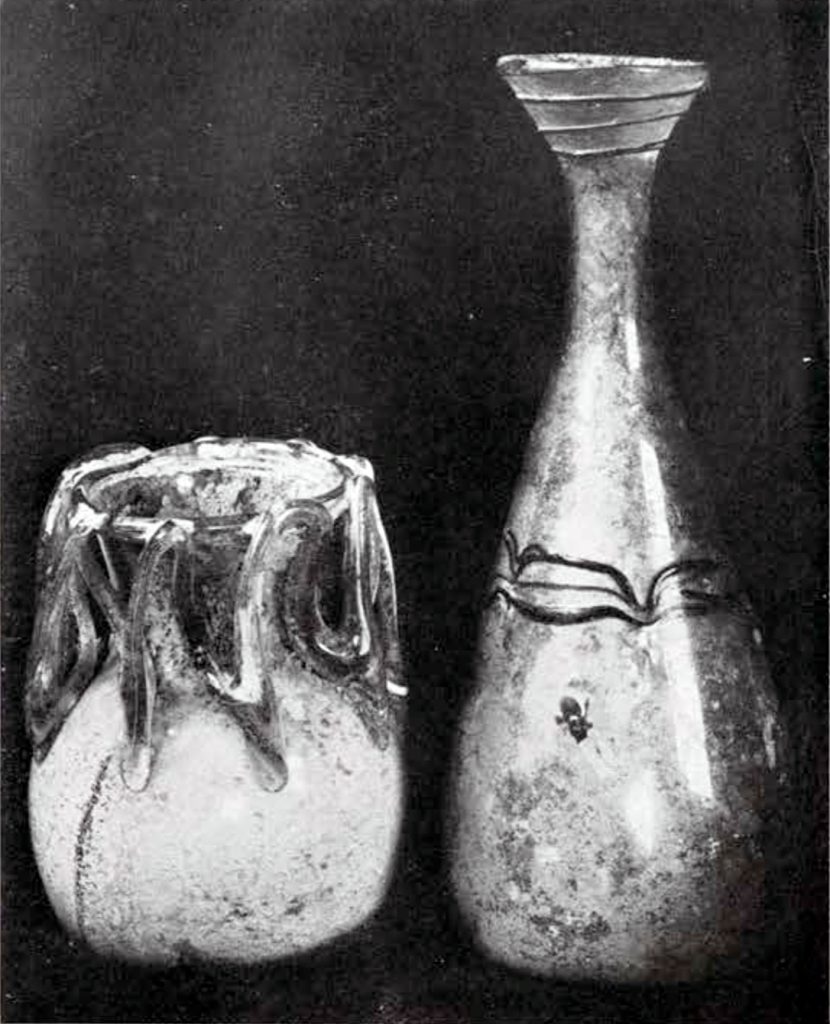

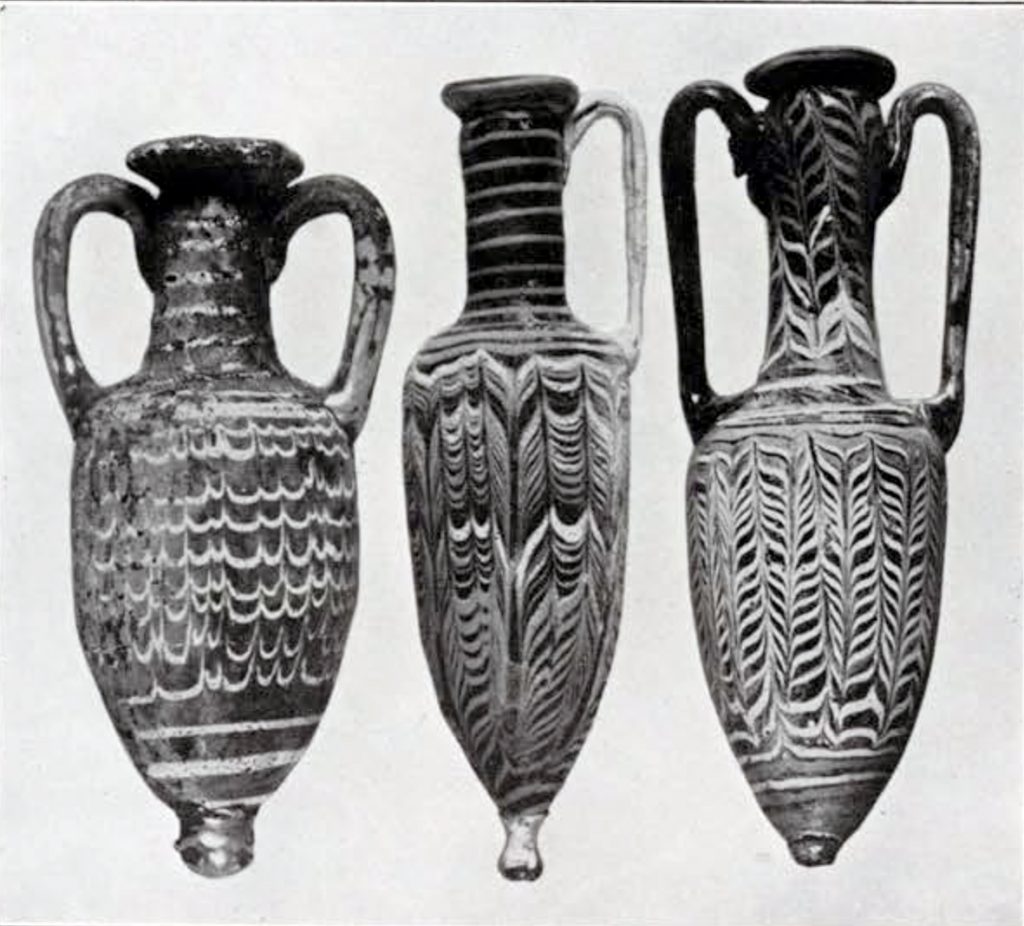

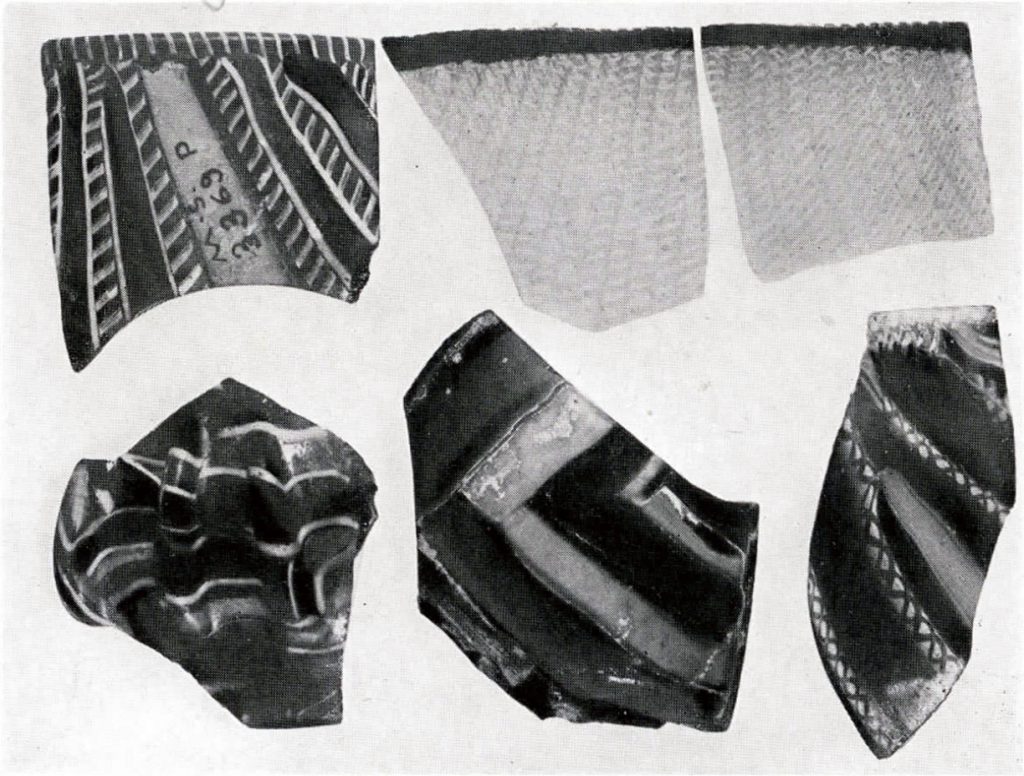

The oldest class of vases represented in the collection are those of Fig. 96, usually known as “primitives.” Made before the invention of the blowing-tube, they display an archaic technique which consisted of modeling the vase over a core. Decoration was achieved by laying threads of variously colored glass over the surface of the vase while it was still hot, and then rolling the whole upon a smooth stone until the threads were pressed in. Wave patterns were probably made with a comb-like instrument, to every tooth of which a thread of glass adhered, so that by moving the instrument in a curved course over the vase, a wave pattern with strictly parallel lines was secured. This technique first practiced in Egypt during the XVIII and XIX dynasties was continued until the invention of the blowing-tube not only in Egypt but also in other parts of the Mediterranean.

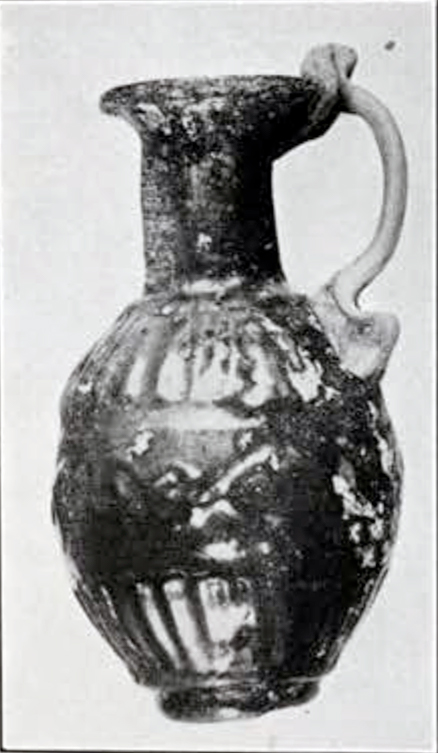

Another type well represented in the collection is that in which a mould was used. In the early stages of this technique, the glass was poured into moulds; later it was forced in by the blowing-tube. Before it was entirely cool, the glass was removed from the moulds, each of which had the form of half a vase, and the two parts joined. This method was practiced in Phoenicia from the Hellenistic time, especially for the manufacture of small jugs known as Sidonian vases. They are frequently hexagonal in form and are often made of colored glass. In the Museum’s collection is one of white opaque glass, one of dark blue, one of yellow and two of a rich wine color (Figs. 101103). Among the moulded ornaments which decorate them are fruits(grapes and pomegranates), birds, floral emblems, and Bacchic symbols, such as wine-jars, libation bowls, and crossed torches.

Image Number: 3556

Museum Object Numbers: MS4953 / MS4954

Image Number: 3555

Another local fabric of moulded vases is that known as Jewish glass. It dates from the fourth century A.D. Two good specimens of this class are included in the collection (Fig. 104 A); they are decorated, as is usual, with palm branches and various latticed patterns, indicating the temple-door.

To give variety of form to his products, the glass-worker sometimes fashioned his moulds in the likeness of fruits, shells, human heads, conventional shapes, and angular bottles (Figs. 105-109). A fine specimen of the latter form in the collection contains remarkable mauve and violet coloring (Fig. 95).

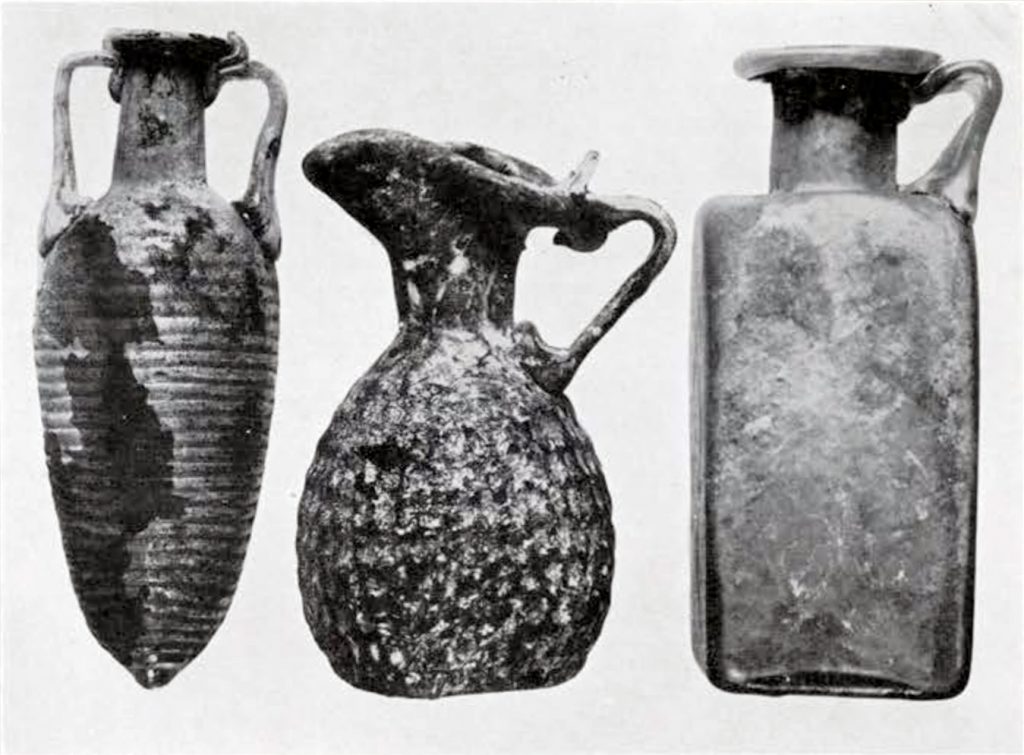

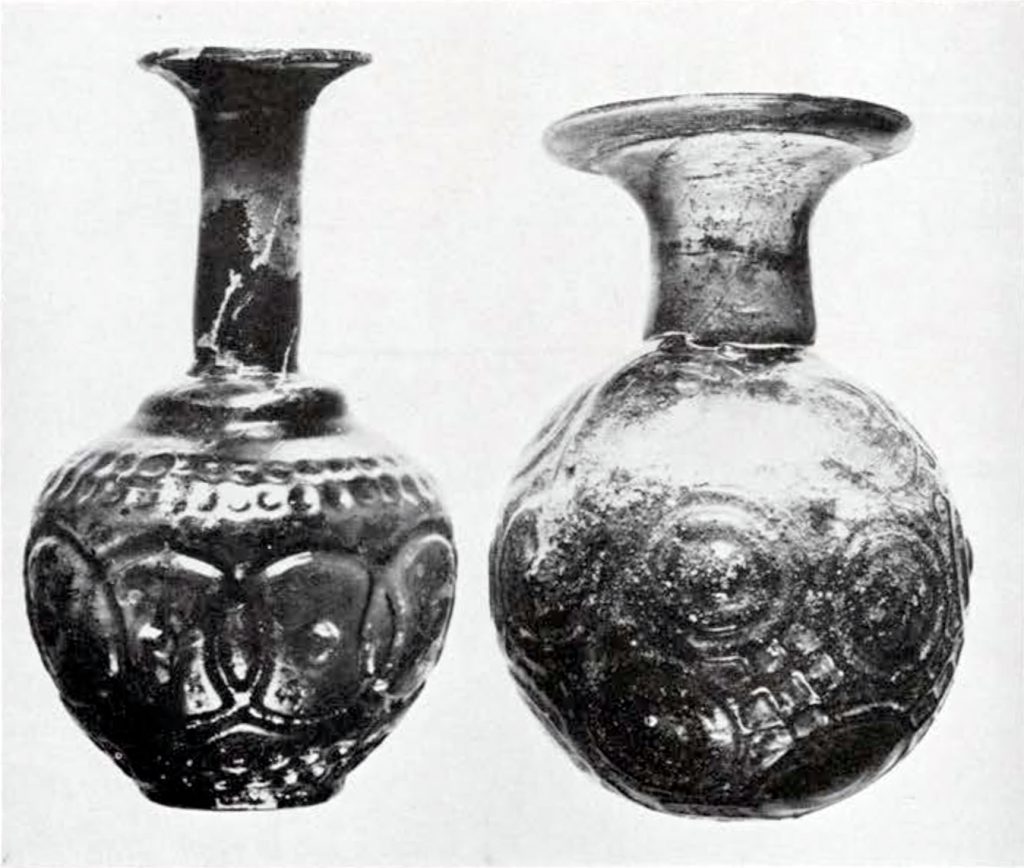

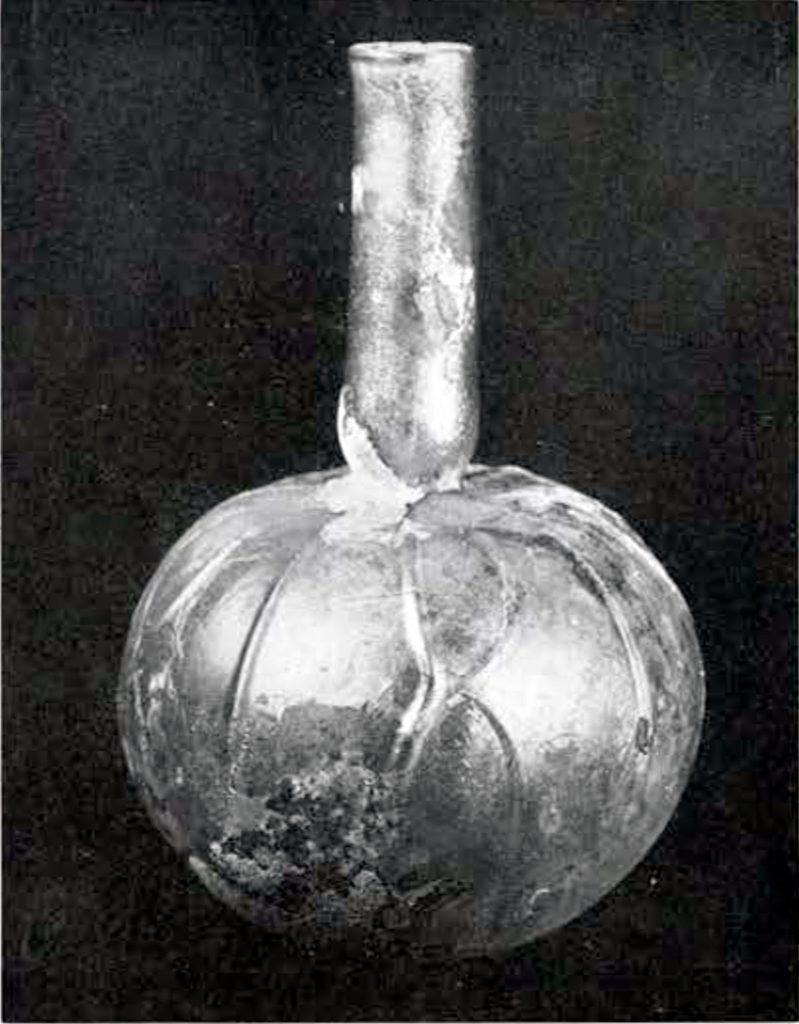

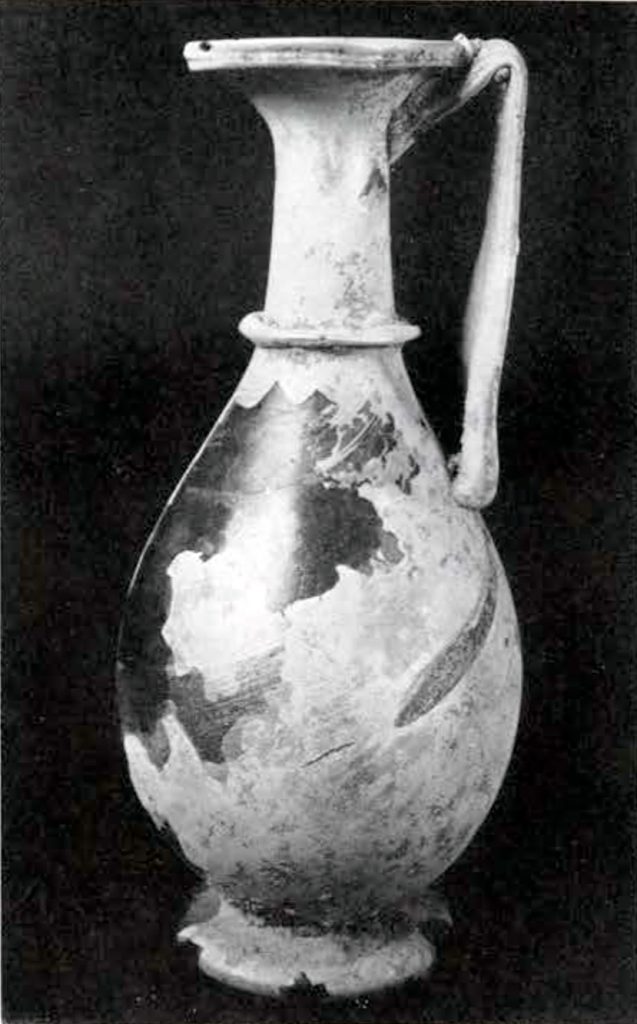

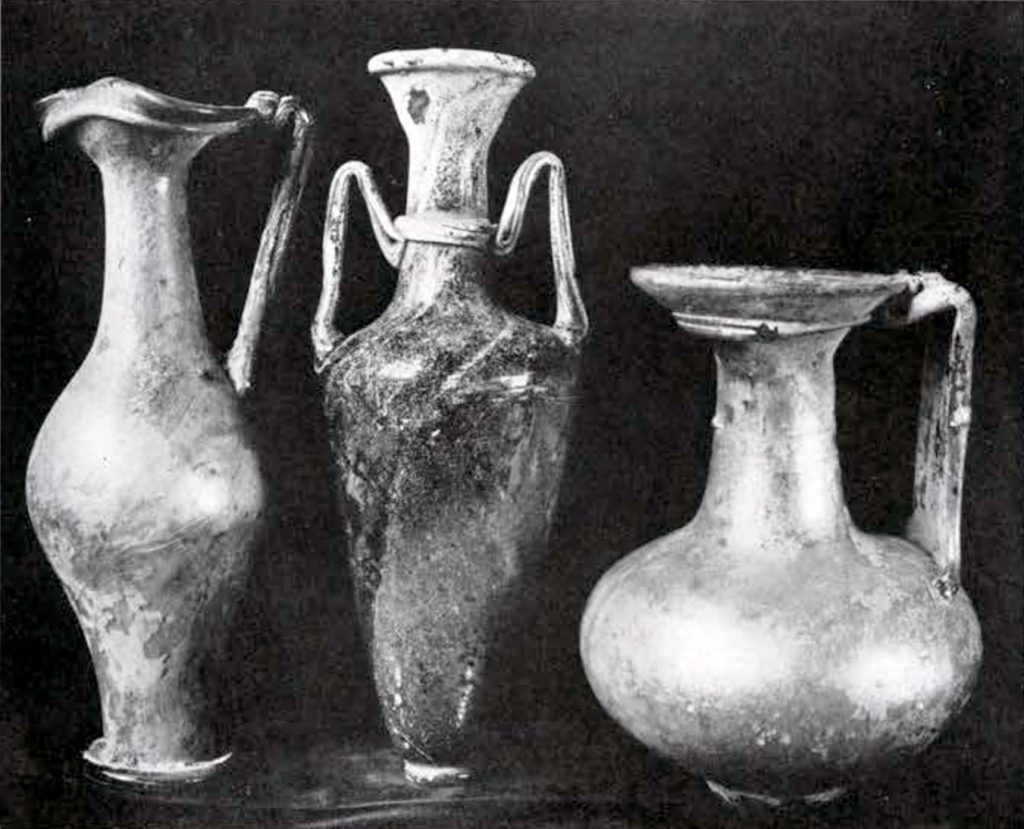

Curious and varied as these moulded bases are, they are generally inferior as regards beauty of form to the plain blown vases, which retain oftentimes the delicacy and lightness of the bubble of glass from which they are made (Fig. 110). The colors of these, irrespective of the iridescent hues which are the work of time, are quite as rich as in the moulded vases, and often constitute in themselves ample decoration. Most beautiful of these colors are a deep cobalt blue, a wine or amethystine color, and a warm golden olive. To these vases photographs do, of course, no justice. Another interesting class of vases is that in which two colors are combined, the body of the vase being of a pale blue and the handles and bands on the rims a deeper shade (Fig. 111 B). Again blown vases are often decorated with threads of glass applied plastically (Figs. 112116). These were at first merely wound about the neck of the vase in imitation of the cord which fastened the sealing of the flask, but were afterwards applied in a variety of ways. In cases where these threads were of a different color from the rest of the vase, this decoration is extremely effective. Other methods of varying the surface of glass vessels were that of pinching the glass while it was still warm so that it has a knobbed or spiked effect, and that of holding a wooden instrument against the bubble of glass so as to impress it with grooves (Fig. 117).

Museum Object Numbers: MS5012 / MS5269

Image Number: 7741

Museum Object Number: MS5255

Image Number: 7761

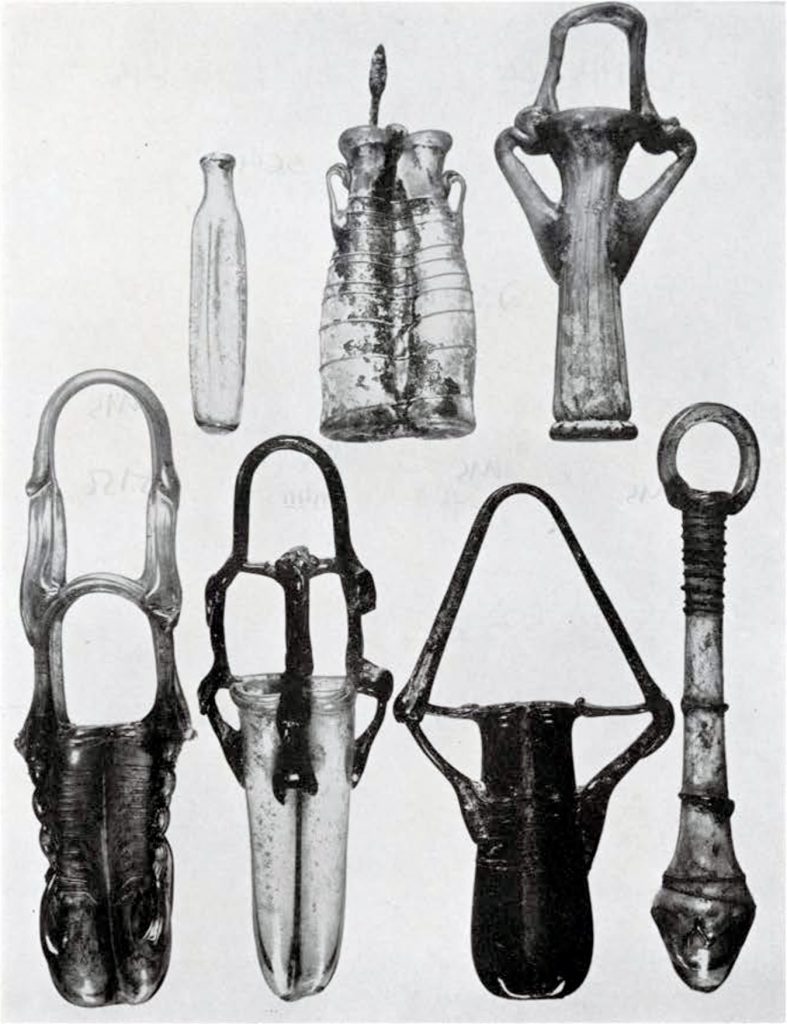

According to the estimates of the German scholar Kisa, whose monumental work, Das Glas im Altertume, supplies all the facts obtainable about ancient glass, more than half of the antique glass vases preserved are flasks, and of these the majority are “tear-bottles,” so-called because a legend ran that the women mourners at funerals gathered in them their tears for the dead. The name is fanciful; in reality they contained balsam or other fragrant oils and doubtless served much the same purpose as do cologne bottles of the present day (Fig. 118). They were single, double, or quadruple and were ornamented with threads of colored glass and with high elaborate handles. They are frequent in the fourth century A. D. throughout the eastern Mediterranean, and are well represented in the Museum’s collection.

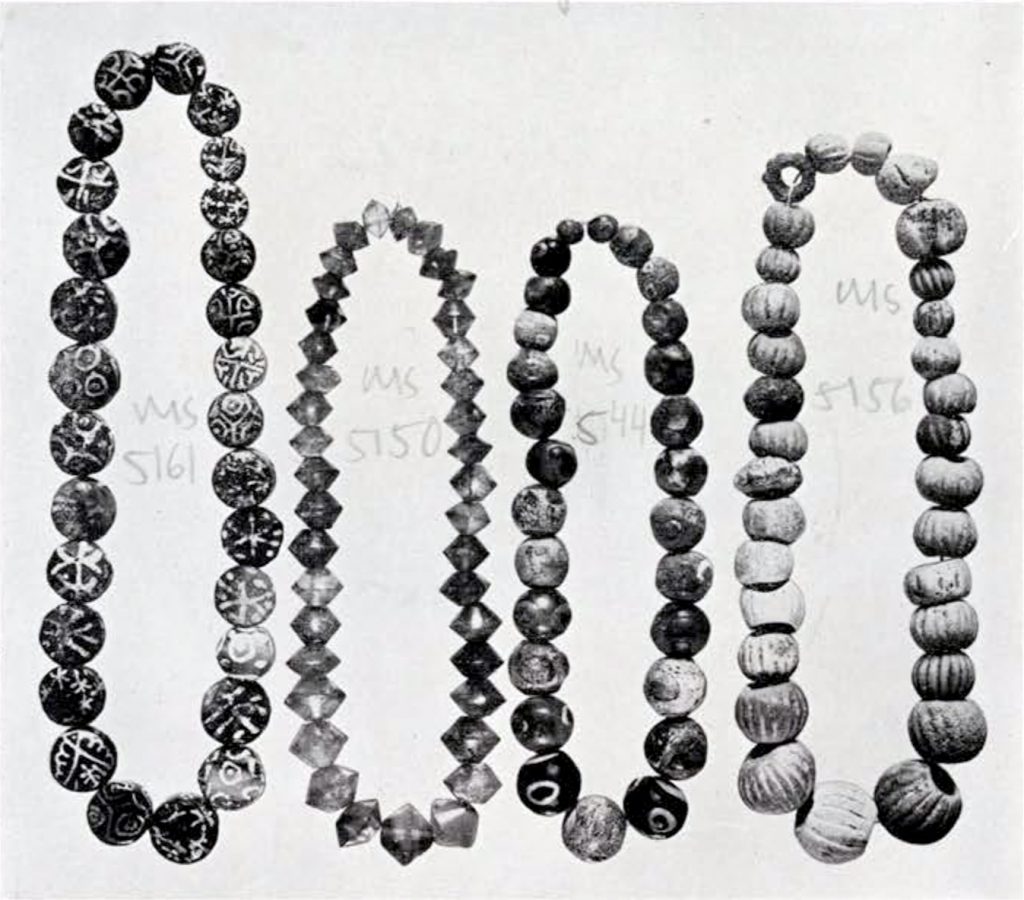

Glass beads, as we have already seen, were made in Egypt at a very remote period. Throughout Egyptian history they continued to be an important article of export; from India to the west coast of Africa have been found these products of Egyptian factories, which were carried first by Phoenician and later by Roman traders. Our collection includes several categories, pale blue glazed beads, beads made to imitate amber, and beads with colored patterns comparable to modern Venetian beads.

Pendants in the form of miniature vases are well represented in this collection as well as bracelets of glass the like of which are worn today by the unchanging inhabitants of the Nile valley.

Of the necklaces of beads included in this purchase Fig. 119, the carnelian, crystal, and amethyst beads are unconnected with glass except certain of the carnelian beads decorated with patterns appliquéed in a very hard white enamel, which, if it does not enhance the lovely color of carnelian, at least bears witness to the skill of the ancients in enameling.

Ancient Mosaic Glass

Before the acquisition of the glass that has been described in the foregoing pages, the Museum was already in possession of a considerable number of specimens of ancient Roman glass, which had been acquired from various sources. Of these specimens the majority were plain blown vases of usual types; others, however, displayed rarer techniques. The only pieces that need be described or illustrated here are some of the fragments of mosaic glass.

Mosaic glass dates chiefly from the first century A.D., and is found in Egypt, the Orient, Greece, and Italy. Our specimens are apparently from the latter source. They are all fragments of a class of bowls probably to be identified with the vasa murrina so admired by classical writers. If so, they are the vases which were first brought to Rome by Pompey after his victory over Mithridates and which some years later sold for as much as $1,000 a piece.

Museum Object Number: 5011

Image Number: 3357

Museum Object Number: MS5013

Image Number: 3357

Indeed, if we are to believe Pliny’s story, the consul Petronius, known for his zeal in collecting art objects, possessed one specimen for which he had paid 300,000 sesterces ($10,000), and which he broke on his death-bed that it might not pass into Nero’s hands. This story is doubtless exaggerated, especially as regards the price paid. In the same passage, however, Pliny goes on to relate how Nero caused the pieces to be gathered up and preserved, a statement more likely to be true and interesting for showing that fragments of vases were prized then as now.

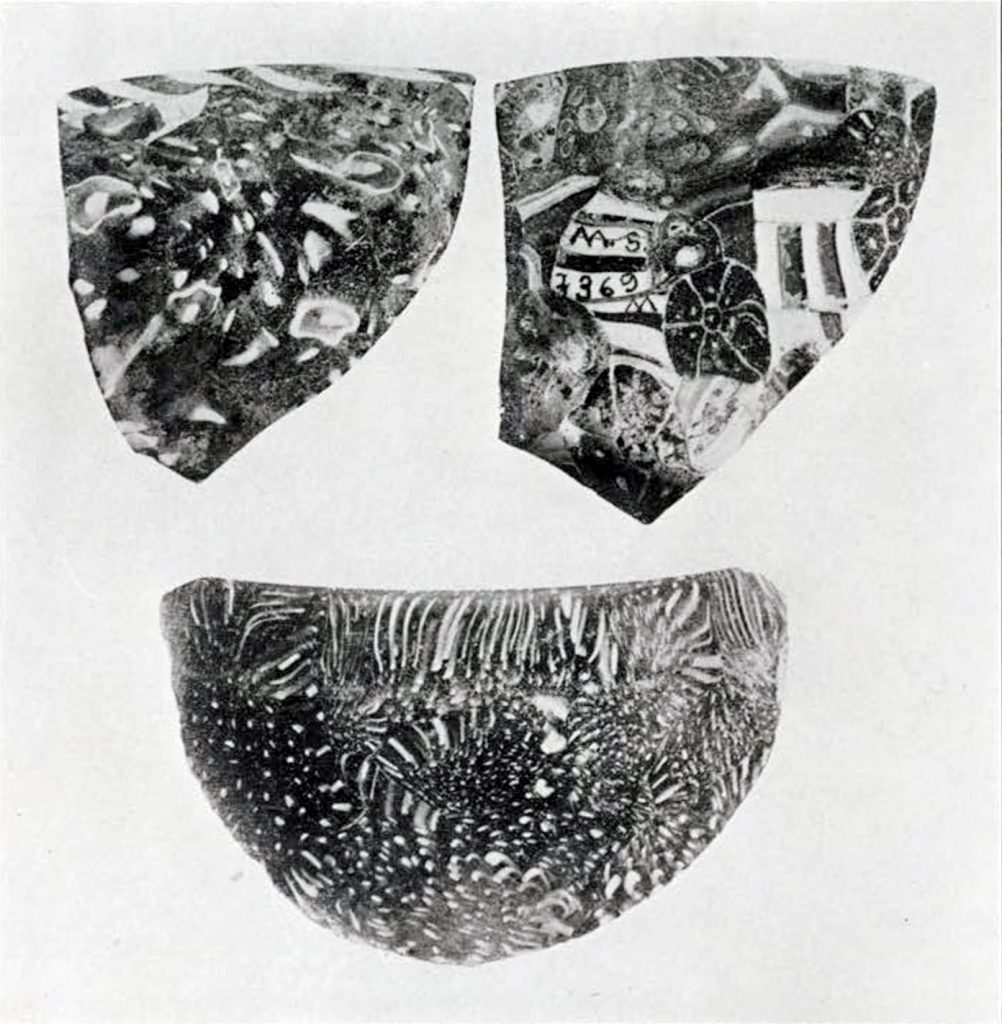

The most famous of mosaic vases are the millefiori bowls, so called by the Venetians who valued them highly. They were manufactured as follows: threads of variously colored glass were combiped in different ways, so that by cutting cross sections through them a variety of patterns was produced. These patterns could be indefinitely varied either in size by drawing out the threads to different lengths, or in shape by cutting the rods made up from fused threads at different angles, into slanting as well as into perpendicular sections. These small sections, when cut, were laid in a terra-cotta mould, and combined either by heating so that they became fused directly one to another, or by blowing a bubble of translucent glass inside the vases so as to unite them. Pieces of millefiori bowls in which the sections of the fused rods were directly joined are shown in Fig. 120; fragments of bowls in which they are held combined by an interior coating of clear glass are shown in Fig. 121. The full beauty of this kind of glass is realized only when specimens are held up to the light; the small sections of the glass rod which extend from one side of the vase to the other are partly opaque and partly translucent, and the contrast in their transparency as well as the rich variety of their hues render their color unrivalled.

Museum Object Number: MS5018

Image Number: 3558

Museum Object Numbers: MS5016 / MS5010 / MS5009

Image Number: 7739

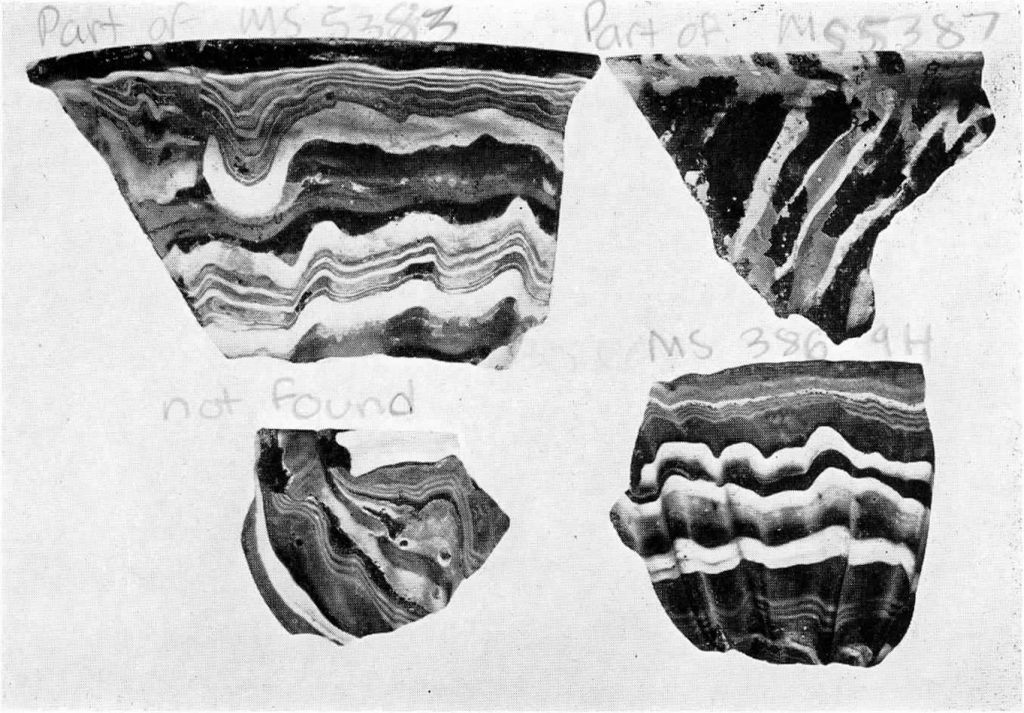

Another type of mosaic bowl was made by cutting the rods made up of fused threads into longitudinal sections. These were then laid in various patterns within the molds and fused by heating. Examples of this technique are shown in Fig. 122. The spiraliform bands and short cross lines of white which appear in some of these fragments were produced by winding threads of white glass about the rod before the longitudinal sections were cut.

Museum Object Numbers: MS5111 / MS5112

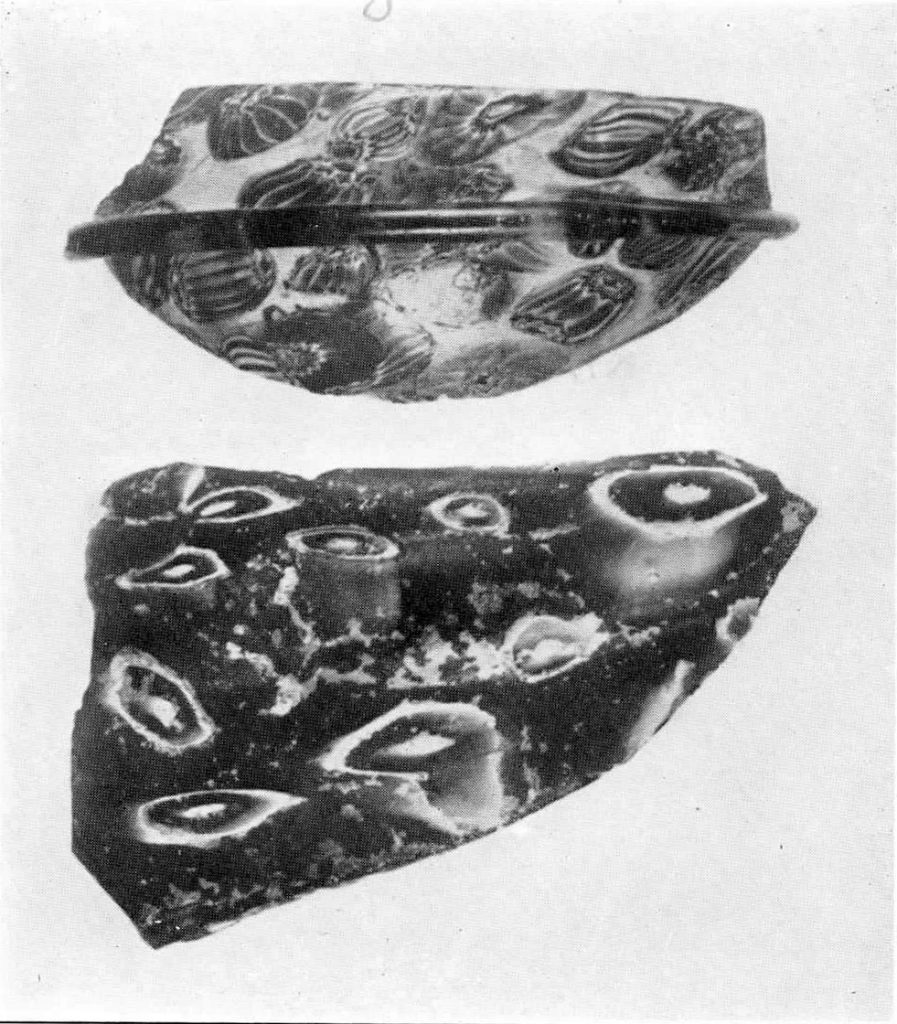

Still another method of combining threads of variously colored glass is that represented by the onyx vases, fragments of which are shown in Fig. 123. In this technique the various threads, some opaque, some translucent, were laid one above another in irregular schemes and the whole mass then heated, picked up on the glass blower’s tube and blown into the desired shape of vase. The grace and effectiveness of the pattern thus produced varied according to the skill of the workman, and also according to the various combinations of color. Some of these vases successfully imitate the effect of veined marbles and other variegated stones prized by the Romans.

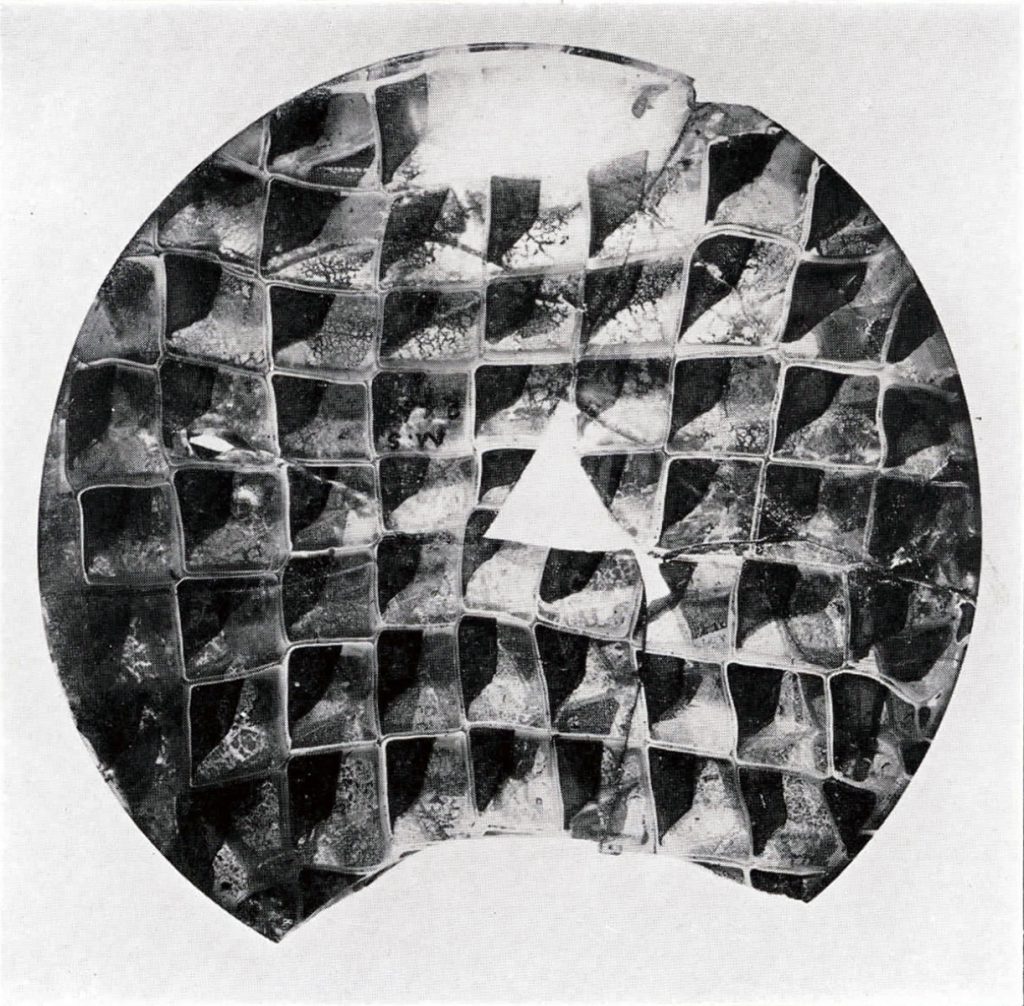

The Museum possesses also one rare specimen of mosaic glass the technique of which is even more elaborate than that of the foregoing fragments. This is the shallow bowl or saucer of Fig. 124. It was found at Chiusi and was acquired for the Museum through the generosity of Mrs. Phoebe Hearst. The specimen has been mended in several places and is not now quite complete; it measures a little less than seven inches in diameter. It is comprised of rectangular pieces, each of which represents a thin section of a bar of glass. Into this bar were fused three threads, one of brown, one of

greenish blue, and one of colorless glass, and the whole, after it had been rendered rectangular in section, was dipped first into white opaque and then into clear glass. Thus the delicate white frames for the checkers were obtained. After the sections had been cut they were laid in a terra-cotta mould. So far the process does not differ materially from that observed before. But upon examination of the broken edge of our specimen it becomes apparent that the bowl is double, and that between the upper and lower layers of mosaic intervenes a thin coating of gilt, which both lends its color to the colorless part of the pattern and enriches the blue and brown glass. Probably the lower covering of mosaic was first fused in the mould, the coating of gilt laid above it and lastly the second layer of mosaic. The bowl is more highly polished on the inside. The outside shows unmistakable traces of the wheel.

E. H. H.

Museum Object Number: MS5114

Image Number: 7763

Museum Object Numbers: MS4988 / MS4987

Image Number: 7751

Museum Object Number: MS4990

Image Number: 7743

Museum Object Number: MS4993

Image Number: 7744

Museum Object Number: MS5027

Image Number: 7740

Museum Object Number: MS5028

Image Number: 7747

Museum Object Numbers: MS5131 / MS4828 / MS5129

Image Number: 3566

Museum Object Number: MS4936

Image Number: 3554

Museum Object Number: MS4926

Image Number: 7742

Museum Object Numbers: MS5107 / MS5103 / MS5102 / MS4935

Museum Object Numbers: MS5147 / MS5150 / MS5161 / MS5156

Image Number: 3643

Museum Object Numbers: MS3369

Image Number: 3586

Museum Object Numbers: MS3369

Image Number: 3586

Museum Object Numbers: MS3369

Image Number: 3585

Image Number: 3584

Museum Object Number: MS2459

Image Number: 3588